Beginner

Beginner

- Learn to play a 12-bar blues, in three different keys, using one shape.

- Study an assortment of strumming and picking patterns.

- Gain a basic understanding of the 12-bar blues form.

As usual, there is more to this lesson than the title implies. We will be working with one chord shape at a time, but over the course of the lesson we’ll study three different shapes. The final example in this lesson incorporates all three shapes to demonstrate how a few basic ideas can provide us with infinite possibilities.

It is important to know that for every chord name in this lesson there are countless shapes—also known as fingerings or voicings—available. For this lesson, I chose what I consider to be the most practical and flexible shapes.

The A7 Shape

A relatively straightforward shape, the A7 form only requires two fingers, and if you can manage to keep the open 5th string ringing and get the G on the 1st string to sound, the rest will eventually make itself heard.

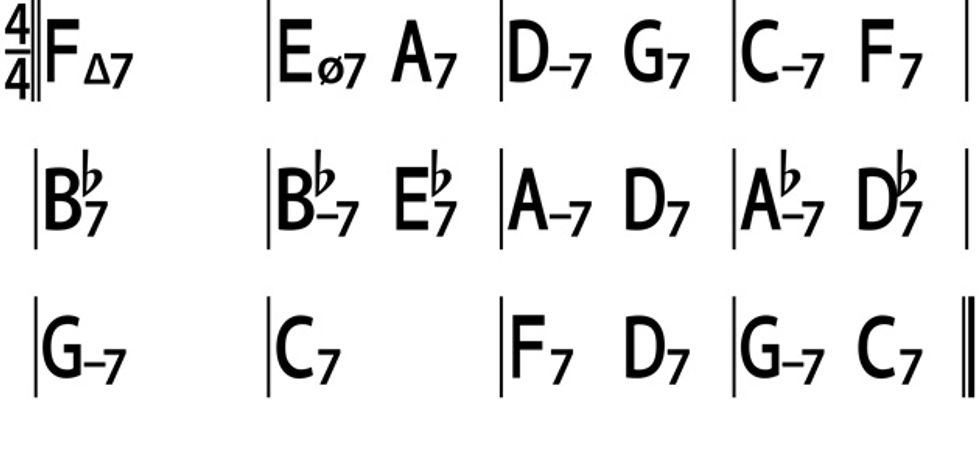

Like all of the examples in this lesson, Ex. 1 is a 12-bar blues using the I, IV, and V chords with a “quick change.” That means we’ll be moving to the IV chord in measure two rather than staying on the I chord for four measures. Both the quick change and non-quick change forms are commonplace in the blues repertoire. Additionally, all examples will move the chord shape(s) up and down the guitar neck, allowing us to play through the entire progression. The real fun begins with modifications you can generate using right-hand rhythmic patterns.

For Ex. 1, merely finger the A7 shape, strum the basic rhythmic pattern, then move the shape from the 2nd fret (think of the barre in this shape as your fret point of reference) up to the 7th fret. Wondrously, the A7 shape now sounds a D7 chord! That’s because even though the shape hasn’t changed, the fretboard position has. A static shape with lots of movement—that’s the secret. To complete the 12-bar blues form, simply move the A7 shape up to the 9th fret for the E7 chord.

Things start to get interesting in Ex. 2, and yes, we do modify the shape ever so slightly. First let’s address the right-hand pattern. You can play this figure using your fingers or a pick (I used my fingers in the audio) as you alternate between the open 5th string and the chord. Meanwhile, your left hand has some work to do as well. You’ll be lifting off your third finger between each A7 chord to allow the 2nd fret notes to ring (with the barre), which creates an A6 chord. This A7–A6 relationship is lifeblood to the blues. This pattern may be noticeably harder for some beginners. If so, don’t concern yourself with moving to the other positions, just work on the A7-A6 movement. Once that is manageable, the shifting shouldn’t cause you too much distress.

Note: When you move to the D7 chord at the 7th fret, you should play the 4th string open for the bass note. Likewise, when playing the E7 at the 9th, play the 6th string open.

The E7 Shape

Ex. 3 continues our theme with the E7 shape. This might be more challenging than the A7 shape, but stick with it—it’s an essential grip. As with the previous example, this one focuses on the right hand for variety. But unlike the previous examples, I used a flatpick when recording this track. Don’t fixate on getting every single note right, but be loose and aim for the essence of the chord. Missing a note or two isn’t a big deal. Only on the B7 shape does accidently hitting the 1st string imply some non-blues color you might want to avoid … maybe not. I kept a fluid down-up strumming pattern throughout this example, but once you have the basics down, feel free to mix it up.

Ex. 4 stays with the same E7 shape, although now we will be very specific with our right hand. This is a common fingerpicking pattern, with the thumb handling the 6th, 5th, and 4th strings, and the fingers picking the rest. At first, focus more on the picking pattern than the chord movement, as it’s the fingerpicking that’s vital to this style of playing. Note that you do not play the open 1st string on the B7 chord, otherwise the pattern is uniform throughout.

The D7 Shape

You could argue I should have started this lesson with the D7 shape, as it is probably the easiest shape to play. Consider my saving it for last as a reward for making it this far! In Ex. 5, I’ve gone electric and added bass and drums to demonstrate how these shapes work in any context.

Ex. 5 is two choruses of a 12-bar. The first sticks with our unwavering right-hand picking pattern and left-hand movement up and down the neck. The second proves that, with rhythmic variation, one can create boundless combinations when playing with simple shapes.

All Three Shapes

Finally, Ex. 6 incorporates all three shapes into two choruses of a 12-bar blues. The first chorus applies the shapes in their most basic forms, the second chorus displays more functionality and complexity.

I hope this lesson has shown you that the modesty of basic chord shapes and the predictability of a chord progression are not a measure of aptitude. A better gauge of proficiency? The capability to imagine and create incalculable variations from a small number of rudimentary concepts.