We will be thinking of dominant chords as they relate to a diatonic major scale. All our examples will be based in the key of G major (G–A–B–C–D–E–F#), but first let’s learn how to make a dominant 7 chord from scratch.

The formula, or numerical representation of a dominant chord, is 1–3–5–b7. Simply, take every other note (starting on the root) and then lower the 7 by a half-step. If we base this formula over our G major scale, only one dominant 7 chord appears naturally: D7 (D–F#–A–C). It also implies the D Mixolydian scale (D–E–F#–G–A–B–C), which is the fifth mode of the G major scale.

Ex. 1 starts off with a single-note line played at a moderately fast tempo. Right off the bat, I outline a D9 sound by adding in the E. Slide down with the index finger on the 3rd string from the 7th to 5th fret to achieve the proper fingering. You will also use your index finger on the 4th string for the slide down from the 5th to 4th fret. I recommend playing a D7 chord before and after each lick to help connect your ear with the sound of the line.

Incorporating double-stops and fragmented parts of a D7 chord are central to Ex. 2. Notice how the passing notes of B, G, and E quickly shift the ear to an Em triad (E–G–B). Passing notes add a nice element to your phrases just by using different note and intervallic choices found naturally in the Mixolydian mode.

In Ex. 3 I outline several descending triads in a phrase that reminds me of how bebop musicians would approach outlining a dominant chord. I start with a Bm7 arpeggio (B–D–F#–A) before sliding down into an Am7 arpeggio (A–C–E–G). (Another great idea is to take just the first two beats of this example and work in out in different keys all over the neck.) I then jump down an octave and hit a Bm arpeggio (B–D–F#). I end with a little open-string pull-off before sliding into a D7 chord.

Ex. 4 is a great open-string lick played in only two positions but has so much going on with it. I like the back end of the lick where the rub of those major and minor seconds clash together. I picked most of the notes and let them ring as long as possible. Using a bit of delay at 250ms helps the notes sustain more and “bleeds” the notes together, but each note needs a separate attack.

Ex. 5 is another great open-string sequence. The fingering can be really tricky here, so start with your index finger on the 2nd string and your pinky hitting the F# on the 3rd string. After the pull-off, use your pinky for the A on the 2nd string. After that, the rest of the lick lays out nicely. With any type of flowing, open-string idea make sure to hold the notes as long as possible.

Since we are approaching these licks from a country angle, it was only a matter of time before we got our hands around a pedal-steel lick. Ex. 6 is one way to navigate a D7 sound—but it’s a real finger twister. The key here is to make your bends surgical and really nail the pitch. Take it slow and try to match the recording.

Ex. 7 is a triple-stop chordal idea with some rhythmic syncopation. If we break down the chord shapes, you can see that they are familiar patterns. I start with an A minor triad and slide into a B minor triad before hitting two G triads—all in the first beat! Knowing how the diatonic harmony works in terms of triads is invaluable for phrases like this.

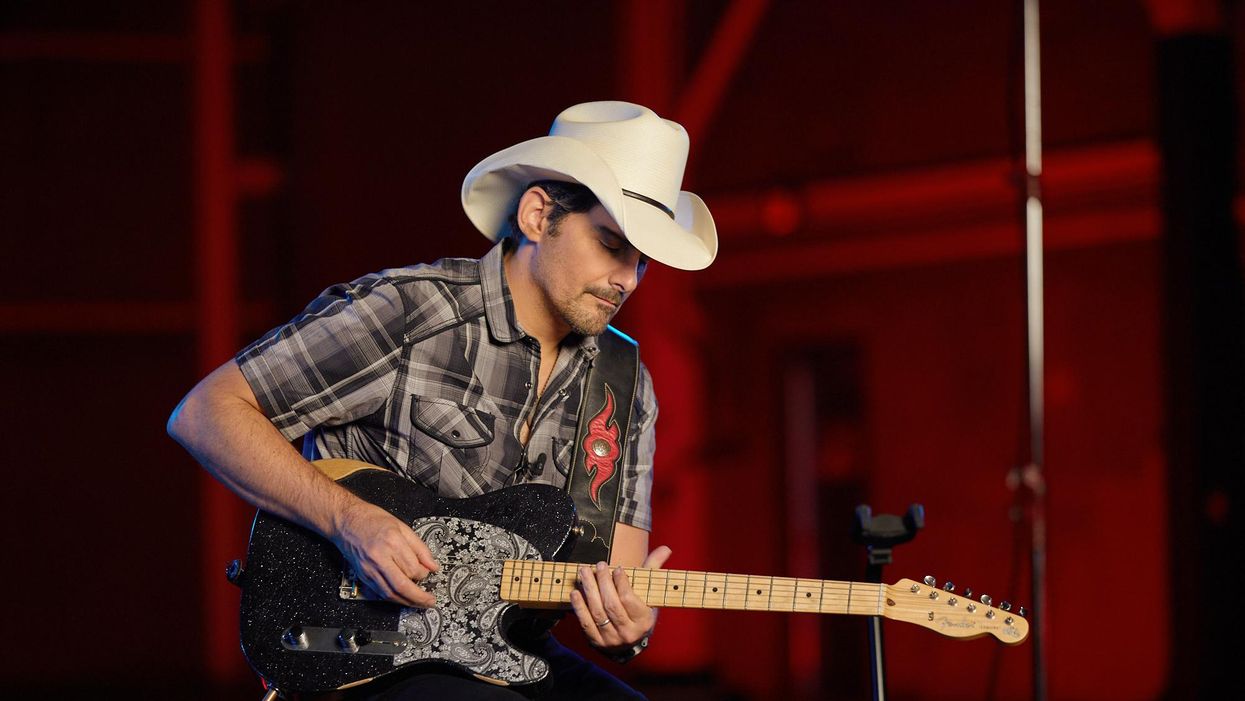

Players like Brad Paisley and Brent Mason are absolute masters of using open-string pull-offs to navigate all over the neck. Ex. 8 is my take on something they might play. Make sure to nail the “cluck” right before the bend as it adds an element of chicken pickin’ to the lick. Grab that bend with your ring and pinky for more strength and control.

As you can see there are lots of ways to be creative with just seven notes. Take even just a tiny piece of these phrases and see if you can work them into your own playing. Until next time!