Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Learn how to incorporate simple arpeggios into your solos.

• Understand how to combine arpeggios.

• Develop phrases to play over challenging chord progressions.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

Arpeggios are one of my favorite musical elements and one of my favorite topics to teach. For many guitarists, arpeggios fall into the bucket of concepts that are simple to understand but extremely difficult to implement in a solo or arrangement. In truth, they don’t have to be difficult. This lesson will focus on ways to practice arpeggios and apply them to your playing. We’re going to cover a few different scenarios here, including simple ways to incorporate arpeggios into chord progressions, different ways to voice the arpeggios, and finally how to apply arpeggios to challenging chord progressions.

In this lesson I’m going to try to be as light on theory as possible and focus on applications, but a little theory will help ground us in a common language. The examples are designed a little less as licks and more as guides to help you generate your own material and create your own music.

Basics

What’s an arpeggio? It’s the notes of a chord played one at a time. That’s it. Nothing more. Nothing less. And don’t read too much into this. An arpeggio doesn’t have to ascend. It doesn’t have to descend. The notes don’t have to start from the root or be in a particular order, and so on. Don’t overanalyze the concept.

When I think about arpeggios, I always come back to one of my favorite guitar solos, the epic duet from “Hotel California,” which is 100-percent based on arpeggios and sounds amazing. Check out 5:35 in this clip (or watch the whole thing because it’s great):

The concept is so simple it’s shocking. It’s a three-note pattern based on the chords in the song. There’s not a single note in either guitar part that’s not being played in the chord progression the guitarists are soloing over ... and that’s why it sounds so good. There’s a powerful connection here: Play the notes of the chord progression in your solo and it’ll be great.

The Four-Chord Thing

Let’s start this lesson in a similar way to “Hotel California” and begin with a chord progression. Not just any chord progression, but one of the most famous chord progressions in popular music, the mighty I-V-VIm-IV. To reinforce just how ubiquitous this progression is, all you have to do is watch this clip:

It’s funny and it’s true! This is a great chord progression to start with because you can apply this lesson and play over a ton of great songs to practice. Let’s start in the key of C major, where our chord progression will be C-G-Am-F. (We can totally transpose this progression into any key we need to, but let’s just start in C.)

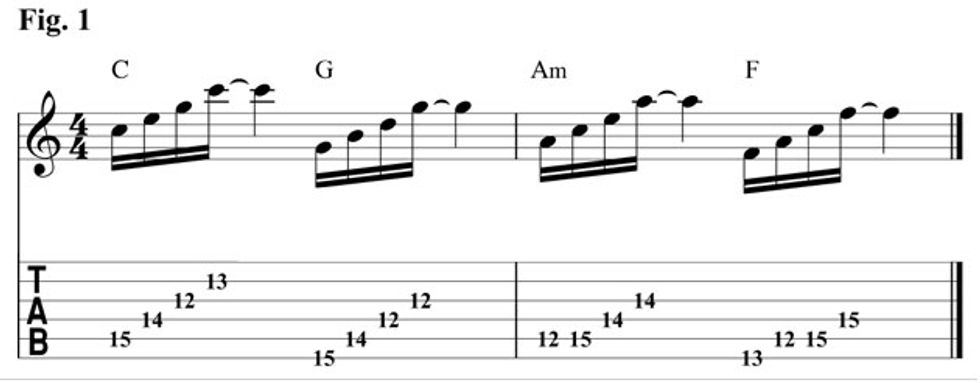

Let’s start with what we’re not going to do (Fig. 1).

Why aren’t we going to do that? Well, because I don’t think it sounds very good unless you can play it really, really fast, and then it starts to sound amazing … check out Jason Becker absolutely tearing up a bunch of arpeggios:

So where does that leave us mere mortals? Well, we’re probably not going to play as fast as Jason Becker, and we’re probably not going to learn our arpeggio shapes across the neck well enough to pull that off in this single lesson, but there’s a ton we can do with just a few simple arpeggio ideas. Let’s start out with the chord progression. This isn’t a long progression, but here are the chords looped a whole bunch of times so you can practice along.

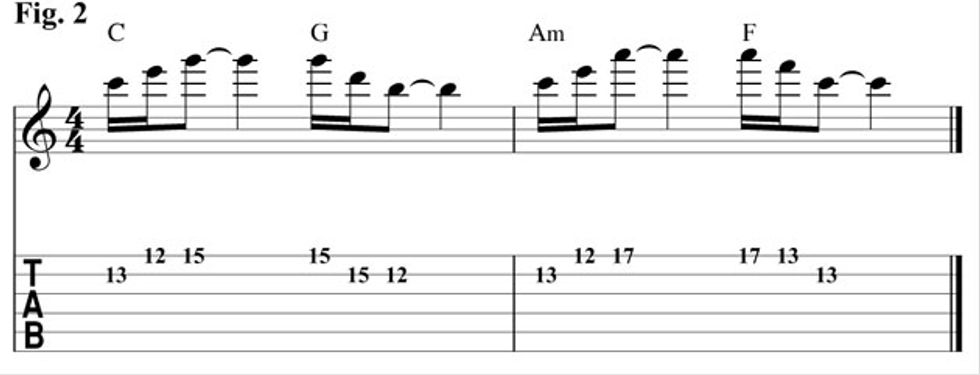

And here’s Fig. 2—our first example over that backing track.

I tried to connect the arpeggios without jumping around. The whole idea was to stay on the top strings and not move around too much. I also wanted to avoid sounding like I was trying to play arpeggios. It’s meant to be simple, but you can hear how it can be a great starting point.

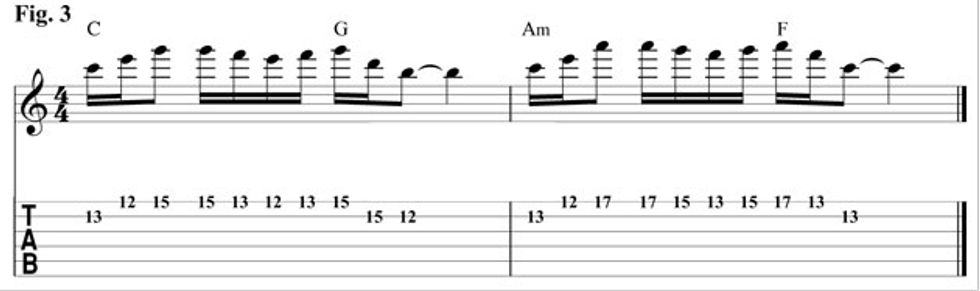

Now in Fig. 3, let’s dress it up a bit more to see where we can take the idea.

I still have the original arpeggio in there, but I added a few scale tones here and there to connect the arpeggios. The idea is to make music, not to just play something for the sake of playing it. If you start from the framework of the arpeggios and then fill in the blanks with scale notes or passing tones, you can generate some pretty neat phrases.

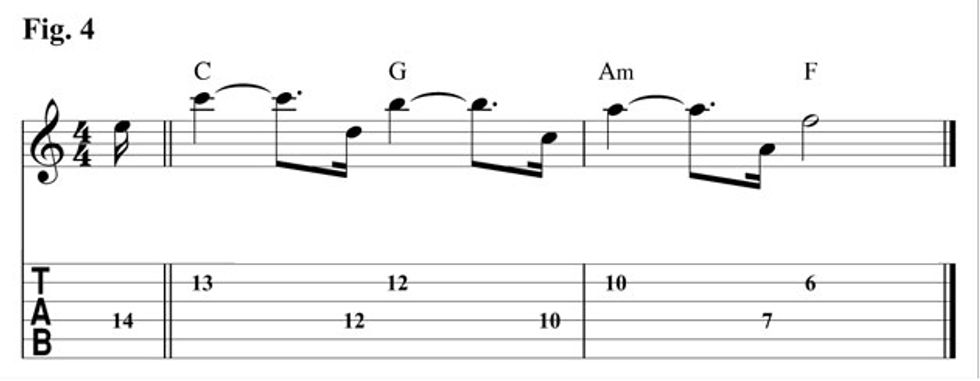

Fig. 4 takes the same notes from the arpeggios in the last few examples and goes the other direction by making it less complex. We’ve removed the scale tones and cut the arpeggios down even further. We’ve also moved it down the neck a bit to change things up.

I’m playing only two notes from each arpeggio, and while it isn’t technically a full major or minor arpeggio (which should have three notes in it), that’s fine because the lick was generated from the full arpeggio. Note that I’m creating melodies and licks using arpeggio shapes. I’m just not playing every note in a given arpeggio, which is fine because we’re generating ideas—spinning out new phrases from simple materials.

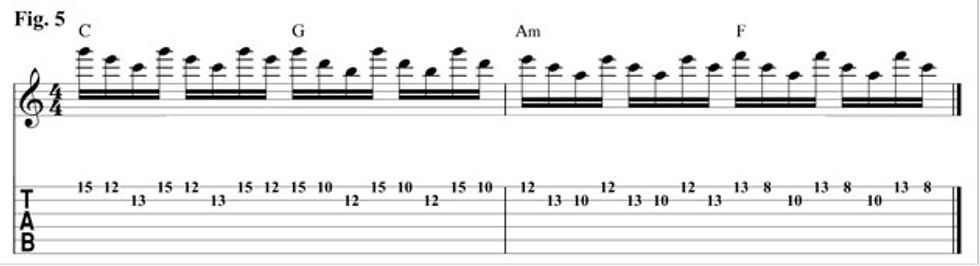

How far can you take this? You can run with it—literally. Check out this lick in Fig. 5: It uses the same basic arpeggio shape, but runs it down the top two strings. It’s the same material we were using before, but we’re putting the arpeggios into different inversions and playing them in a few locations down the neck. Variety really helps us sound unique, and brings us full circle with the “Hotel California” example that started the lesson. This is a similar concept to what they did, just applied to C-G-Am-F.

What better way to close this section off than with a video of Paul Gilbert? He is one of my favorite players and this is such an amazing clip:

Now, before you decide to quit forever, please keep this in mind: Not only does Paul has someone else helping to move the virtual capo around, but the guitar has three strings, tuned to the same pitch in different octaves. The effect is riveting. This performance consists of simple arpeggios played so fast they melt together and sound like full chords in their own right.

Next, let’s take a look at how to spread out and open up our sound.

Spread Out

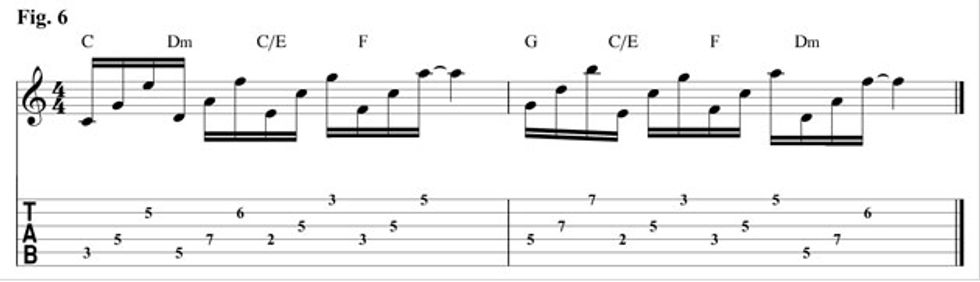

Another way you can use arpeggios to generate new ideas is to mix up the order of the notes within the arpeggio. If you always play sequentially up the arpeggio, it’s all going to start sounding the same. Check out this basic example (Fig. 6) that Eric Johnson loves to play:

This simple idea just takes your basic 1-3-5 arpeggio and moves the third up an octave. You end up with 1-5-10, where the 10 is just the 3 played up an octave. Move this recipe through a few different chords and you have something unique. In the example, I only use chords in the key of C, but I throw in some chord inversions as well to keep things interesting.

I can’t think of a better example than Eric’s masterpiece, “Cliffs of Dover.” There are so many amazing things about this video, but you can hear him use the spread-out arpeggios at 4:17, where he really starts to explore some different harmonies.

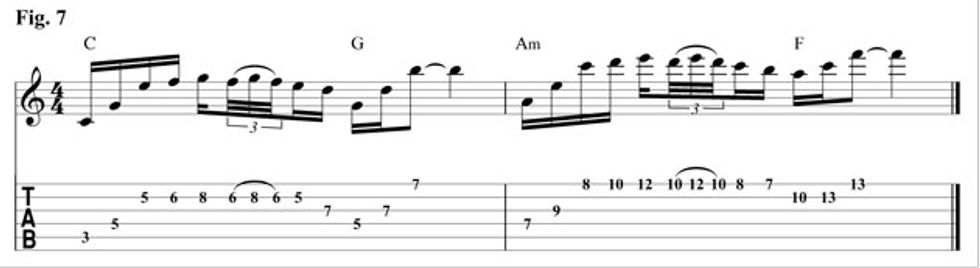

Let’s try to combine the original C-G-Am-F chord progression with our new spread arpeggio shapes. In addition, we can use some scale tones to connect the arpeggios across the neck. The result is Fig. 7.

We can do more. Yes, there’s more to explore.

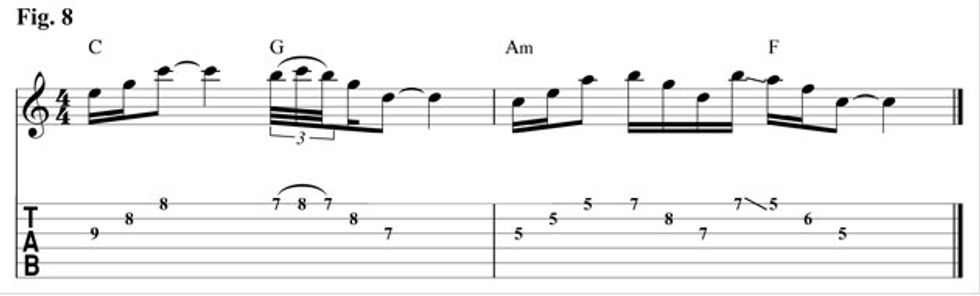

If you only play exactly the notes in the chord progression, it can be a little limiting. One way you can continue to generate materials is to include additional arpeggios within the same key. It’s the same idea as a passing tone, but this time, you play a passing arpeggio. Let’s go back to our original example of C-G-Am-F. We’re going to target the Am chord and add another arpeggio between the Am and the F chord. Let’s add a G arpeggio after the Am, which basically steps down the harmony (Fig. 8). Notice how Am-G-F and creates a nice cascade down to the F chord.

It’s a really nice sound, and you can do this as long as the extra arpeggios you’re adding don’t conflict with the overall harmony. Ultimately, you have to let your ears be the judge of what works and what doesn’t.

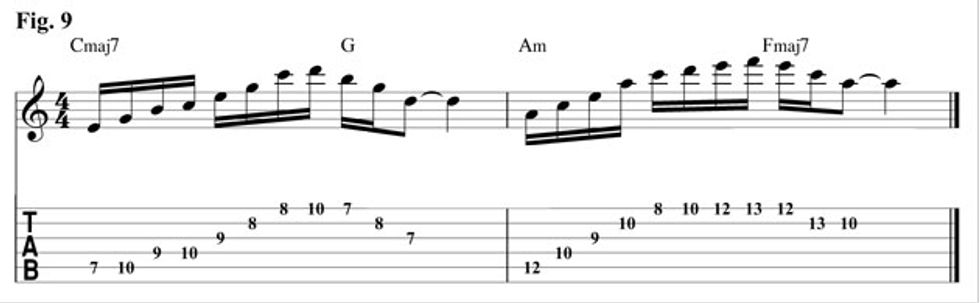

One more way that we can expand our sound is to extend the chords and make them a little taller by turning some of the chords into seventh chords. If we turn the C and F triads into major 7 chords, as in Fig. 9, we can inject some color into the passage.

Not only does it extend the sound, but it also makes it easier to connect the arpeggios on the fretboard.

Tough Progressions

Another great thing about arpeggios is that you can simplify extremely difficult progressions by using arpeggios to navigate the changes. For example, take “Giant Steps”—a famous jazz tune by John Coltrane and a rite of passage for all jazz musicians. It’s really stinking hard to play over because the chord changes are fast and the tune changes key after only a few chords. It’s thrilling, though. Check it out:

Before y’all freak out. No, we don’t have to play it that fast. Check out Pat Metheny’s bossa nova version of “Giant Steps” at a much more reasonable tempo.

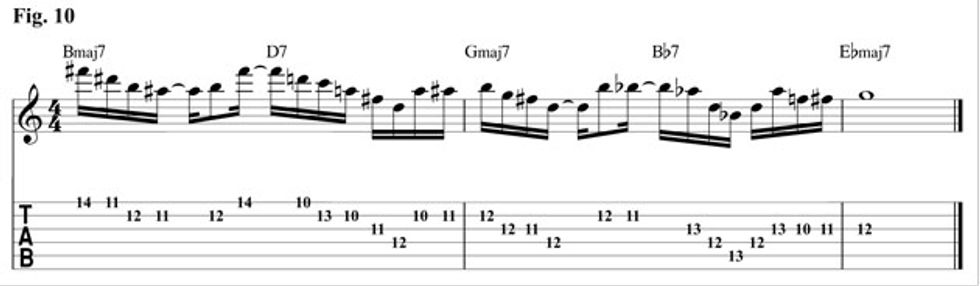

What we can do is start to break the harmony down into pieces. Let’s just take the first three measures in Fig. 10.

The chords themselves don’t really seem to relate to one another very well. Finding a scale that traversed through this would be very difficult. (Hint: There isn’t a single scale for this set of chords.) What we can do is see if there’s a way to connect the arpeggios without flying all over the neck. And luckily for us, there is. The lick illustrates that you don’t have to go flying across the neck in order to hit the right notes. We’re able to walk through the harmony largely using arpeggios in the 10th and 11th positions.

For the first two chords, we focus on F# as a common tone in both the Bmaj7 and D7 chords and construct a line that pivots around the F#. For the G and Bb7 chords, we focus on the B in the G chord and the root of the Bb chord. The rest is basically just arpeggios of each chord with passing tones to smooth things out. Notice how Am7 and D7 are basically just straight-up arpeggios with a passing tone to the 9th on the D7 chord. The long G on the Ebmaj7 chord is just there to give you a break from having to keep playing so many notes.

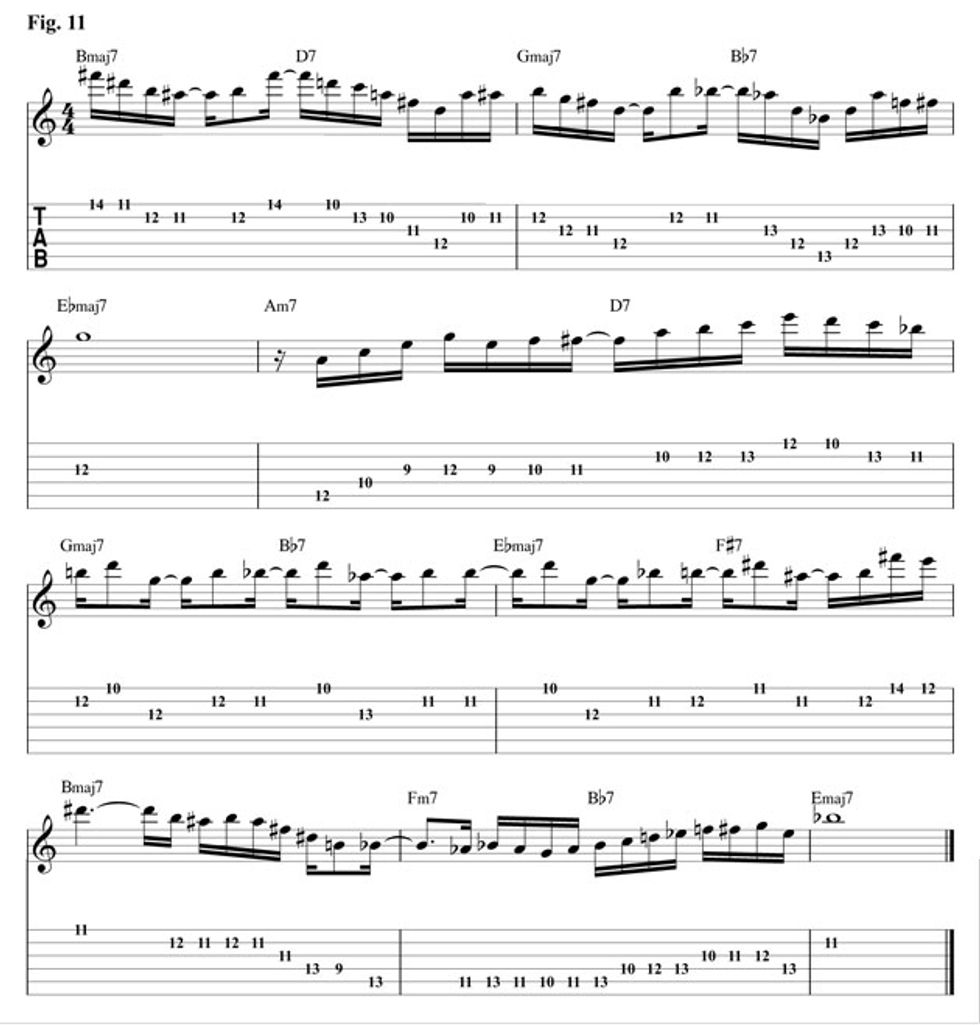

Now if we apply this to the first eight measures of “Giant Steps,” we end up with an easy way to traverse the progression without having to have a PhD in Jazz Harmony. Fig. 11 combines a lot of what we’ve talked about in this lesson, but applies it over a more challenging chord progression. We’re using small arpeggio shapes, scale connections, and seventh chords to help tame this difficult chord progression. The end result is something that’s fluid and works well over the chords.

Pay attention to measure five. I did my best to keep the movement as constrained as possible by popping back and forth between a few notes, largely G, B, and D, and only altering those notes when the chord progression absolutely requires it. We’re still thinking arpeggios, but to avoid playing too much, we’ll let the rhythm take over and play with more of a syncopated feel while keeping the notes simple. The end of the example is just a long descending Bmaj7 arpeggio, which is followed by a scale run that heads back up the neck, landing on the note Bb, the 5 of Ebmaj7 for some well-deserved rest.

There are thousands of ways to play over this tune, and this example captures a single improvisation. If I played it again, it would be completely different, but the concept of using arpeggios to outline the harmony would be the same.

Also, so you can practice over the first eight chords at home, here’s the progression looped a few times. Each pass of the backing track includes a two-bar break so you can catch your breath!

To wrap up this lesson, I selected a video of modern jazz guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel playing “Inner Urge,” a jazz standard that is famously hard to play because it traverses through a number of difficult tonal centers at a pretty rapid pace. Check out how easily he moves through the solo. He’s connecting the chords by playing a number of arpeggios to outline the harmony, while also using passing tones to connect everything.

While arpeggios are a simple concept, they sound great and can really change the way you play. Take the concepts here and apply them to your favorite songs and chord progressions to craft some amazing solos, licks, and riffs. Go slowly and enjoy yourself—that’s what music is all about. Good luck!