You know those sneaky song intros, where a guitar riff tricks you into thinking the beat is somewhere other than where it actually is? Then the drums come in, and it feels like the world tilts on its axis. Those parts remind me of the famous optical illusion that you alternately perceive as a portrait of a young woman and an old one.

These intros are worth studying, and not just because they capture the listener's ear within a song's first few measures. If you can develop the ability to hear how a pattern might start at any point in the measure, you can remedy countless musical problems. It's a bit like working a Rubik's Cube, except there's a good chance you can solve the puzzle within a couple of minutes.

Have you ever concocted a great guitar idea, only to realize that it gets in the way of the vocal or doesn't quite groove with the bass and kick drum? Being able to shift parts in time can resolve such traffic jams, make a mundane part thrilling, and transform a cool riff into an epic one. (The formal name for this technique is “rhythmic displacement.")

Facebook Doesn't Always Suck!

This month we'll look at how crafty guitarists have employed this technique. You know, like in … that song. You know the one. It's by … that band.

Okay, I don't have the world's greatest memory. So I posted this to Facebook a few weeks ago:

Can you help me out, musical hive? For an instructional column on rhythmic displacement, I'm looking for song examples where the guitar enters alone, and you THINK you know where the downbeat is, only to be surprised when the drums enter, revealing that you've been hearing it backwards. Thanks!

I knew my friends were helpful and hip, but I didn't expect nearly 400 comments! Some songs got mentioned many times, and some suggestions, while rhythmically cool, simply weren't examples of the technique. Particularly interesting were the songs that actually start on 1, just like you'd assume, but rhythmic complications (like syncopated drum parts) make the final groove surprising nonetheless. Examples include Fleetwood Mac's “Go Your Own Way," Tool's “Jambi," and the Cars' “Just What I Needed."

When the smoke had cleared, we had a list of nearly 80 deceptive-intro songs, which you can download as a PDF.

Cars guitarist Elliott Easton, whose riffs got cited many times, offered his own simple yet classic example: the opening riff of the Beatles' “She's a Woman." The song begins with a stabbing guitar chord. You might be tricked into thinking it's the downbeat, but when the drums enter, we realize it actually falls on beat 2.

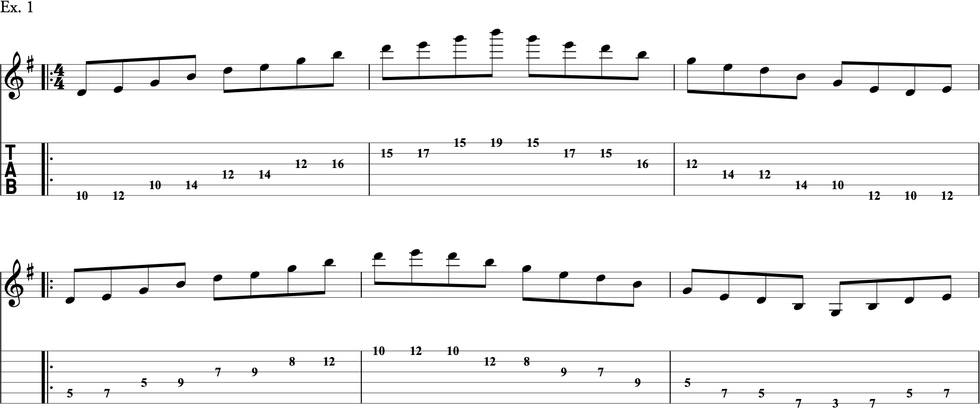

Here's a rhythmically similar example, heavily altered to dodge copyright infringement (Ex. 1).

Do you hear it starting on beat 1 or beat 2? Our ears tend to assume the first note of a riff falls on beat 1 until proven otherwise. But there's no “right" answer—this pattern could start on any beat within the 4/4 measure.

Let's add drums to nail it down (Ex. 2). You hear the pattern two ways: first, starting on beat 1, as we might have first assumed, and then starting on beat 2, Beatles-style. You hear the pattern twice in each location, and then I repeat the entire thing. (I use the same format for the following examples as well.)

Click here for Ex. 2

If you're in the habit of listening for the backbeat, you might never perceive the pattern as starting on the 1. It's the same for any song that starts with a snare hit on 4, or a reggae tune where the first thing you hear is an offbeat guitar skank. But sometimes the beginning is truly deceptive, as in Ex. 3.

Sounds like it starts on 1, right? But it works better on beat 2, where it adds an element of surprise and better reinforces the backbeat.

Click here for Ex. 4

You hear the same displacement in the Smiths' “This Charming Man," Sharon Jones and the Dap Kings' “Be Easy," and Joe Jackson's “One More Time."

What a Difference an Eighth-Note Makes!

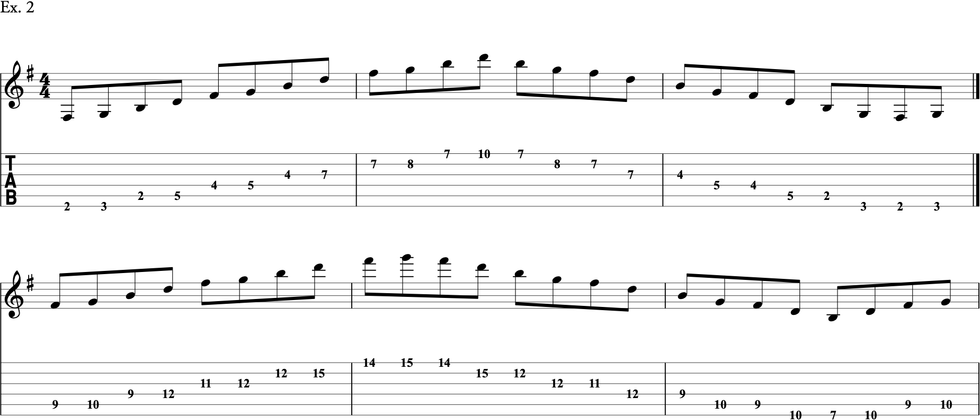

So far, we've looked at patterns displaced by a quarter-note. Things get trickier when you shift by an eighth-note. Check out Ex. 5. Again, it sounds like it starts on 1.

In Ex. 6, you hear the pattern starting on 1, and then starting on the “and" of 4 (an eighth-note ahead of the downbeat).

Click here for Ex. 6

The displaced version grooves better, and not only because the rhythm is less predictable. In the first version, the chord changes fall directly on the beat, which feels plodding and predictable. In the displaced version, the chords change between the beats, adding a syncopated feel that bounces you into the next beat. (Though there are definitely times when you want a boneheaded, on-the-beat approach!)

Ex. 7 is a similar example, inspired by the intro to the Eagles' “Take It Easy."

It sounds like it starts on 1, but it really begins on the “and" of 4. (How many fights have erupted between guitarists and drummers when tackling this tune in cover bands?) In Ex. 8, the second version is definitely groovier. The rhythmic accents and chord changes both occur right before the downbeat, catapulting you into the next measure.

Click here for Ex. 8

You hear other deceptive “start on the 'and' of 4" intros in “Start Me Up" by the Rolling Stones, “Cumberland Gap" by Jason Isbell, “I'm Free" by the Who, and “Sex Is on Fire" by the Kings of Leon. The technique is just as effective starting after the downbeat on the “and" of 1. You hear that displacement in the Johnny Burnette trio's seminal rockabilly track, “Train Kept a Rollin'," PJ Harvey's “Yuri-G," Blink 182's “What's My Age Again?," and XTC's “Wake Up."

Make It Funky: 16th-Note Displacements

You can also displace patterns by a 16th-note. Unaccompanied by drums, Ex. 9 certainly sounds like it starts on the 1.

But Ex. 10 reveals that it's funkier, if harder to play, when shifted forward by a 16th-note.

Click here for Ex. 10

The opening riffs from “Lights Out" by Royal Blood, “Top Secret" by the Yellowjackets, and “Bring on the Night" by the Police also start a 16th-note after the downbeat.

Independent Study

These examples merely scratch the surface. Download the PDF above for many more instances. (The list also includes some cool displacements we didn't get into here.) Can you hear these parts two ways: beginning on the 1, and starting somewhere else within the measure?

Most important, take a fresh look at riffs and melodies that you have created. Can you imagine how they might be shifted in time? Can you play them that way? It's not simply a matter of which version is better. It's about developing the rhythmic flexibility to consider many possible placements for any given part. With that skill, you'll be able to solve countless arrangement puzzles while creating cooler riffs with stronger grooves.