Last week a PG fan emailed me: “Hey mang. Your last two editorials have been boring and seemed fake. Get back to pissing people off with political shit.” It was signed, “Sincerely, Some Dude.”

I don’t know if Dude reads my column in the magazine or online, so I’m not sure if he was referring to this, this, or this. It doesn’t really matter, though—snoozy or not, that stuff was from my lame-o heart. But I get where Dude’s coming from. Truth is, I’ve toyed with writing about today’s topic for the last few months because it feels like half the emails I get are about some “rootsy” musical act or another. Every time I’ve started writing on the subject, I end up feeling mean, though. Like Rodney Dangerfield, despite my occasional fits of snark, I’m a lover, not a fighter.

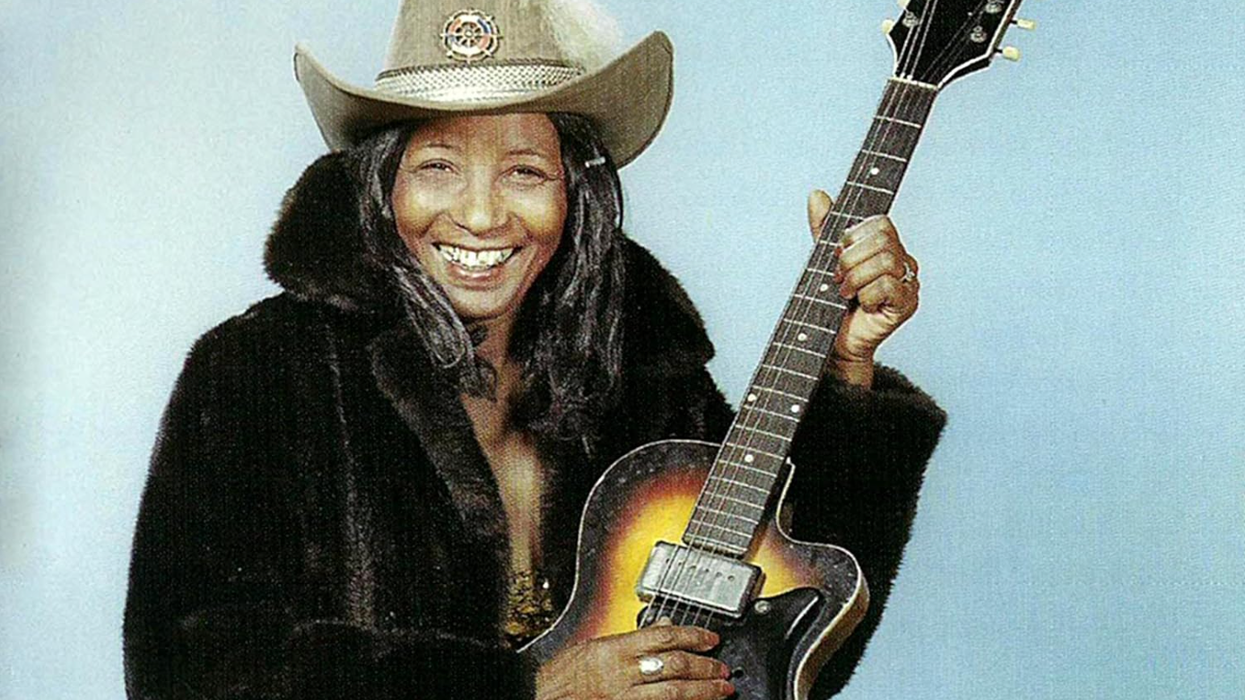

But surely I can’t be alone wondering these things as I click around YouTube and various social-media holes, kicking myself for not investing in beard oil or “vintage” felt hats that look they’ve been meticulously run over by the Ice Road Truckers. You know what I’m talking about—dudes in cuffed denim jackets and at least a medium-sized beard, singing in some generic Southern gentleman brogue from atop a bale of hay. Or maybe a quaint, no-nonsense belle whose name we’re supposed to believe is Something-Something Rose, crooning a “heartfelt strummer” that sounds like it was conceived in a corporate lab owned by the makers of some magnificently mindful new sleep-aid.

If everyone’s suddenly so enamored with Neil Young, why don’t they have any of his musical adventurousness or lyrical rage?

Don’t get me wrong: I’m fine with denim jackets. For the first time in my life, I’ve even been sporting a beard for a couple months now. And, full disclosure, at the last NAMM prior to Covid, I noticed how cool luthier James Trussart looked in one of those vintage felt hats and, in what I can only conclude was a post-NAMM daze, I bought one off eBay. The second I put it on, I realized that, while Trussart totally pulled it off, I looked like a fucking idiot. I put it away forever.

Whenever something starts to feel bandwagon-y, it gives me the hardcore willies. Are we really supposed to believe that, sometime in the last five years, half the guys in the States just collectively decided to look like Depression-era farmhands? Nah. What happened was, the general music-listening populace finally got fed up with cheesy-ass, fake country tunes bullshitting about pickup trucks, lost dogs, and tubing down the river in the hot summer sun. Even some big country artists were like, “How much longer can I do this shit?”

More accurately, the music-industry suits divined from profitability charts that the last stupid trend was winding down and that it was time to pump a crapload of money into something else. But Almighty Data said that “earthy” vibe was still alluring, so they encouraged everyone to try to come across like a good ol’ boy or girl—only with more depth and retro-charming style. Something more “real.” But is it real? It’s very hard for me to listen to or look at most of it and not think of Bo Burnham’s song “White Woman’s Instagram.”

Here’s the recipe so many “Americana” acts seem to be following, as handed down by their favorite soulless “influencer”: Seize upon something “aesthetically pleasing”—but in the most banal, vanilla sense—then clean it up even more, strip it of anything that some OCD asshole might deem a blemish, place it in a sterile, clinically ordered environment, and make it all about all the surface-level stuff so that its potential for mass consumption isn’t ruined by icky natural anomalies.

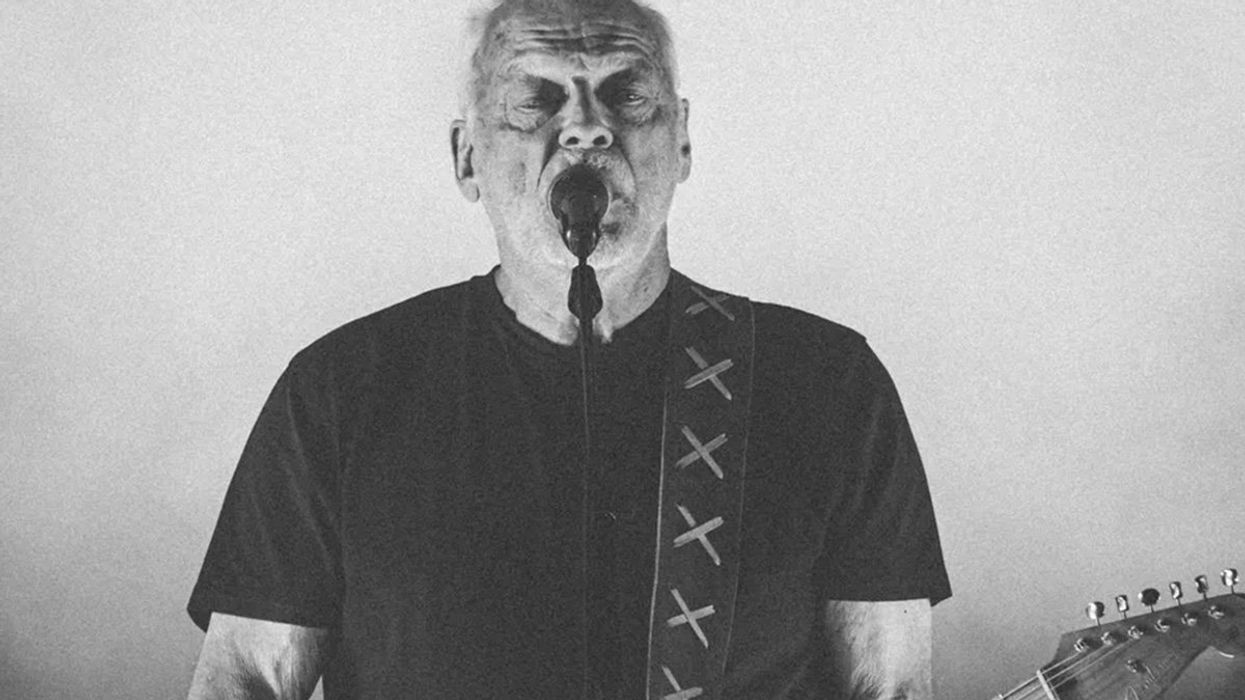

If everyone’s suddenly so enamored with Neil Young, why don’t they have any of his musical adventurousness or lyrical rage? Why aren’t there any screeching, careening passages where shit’s barely in tune? How come the weird-ass natural vocal quirks everyone’s born with are replaced with a boardroom-tested tracheal patina? Neil embraces the chaos. Neil celebrates the fact that, half the time, he sounds like an unhinged Wiccan ready to beat the shit out of you with a a thrice-washed Ziploc full of gnarly granola. Neil’s real.

Can we get some more of that, please?

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)