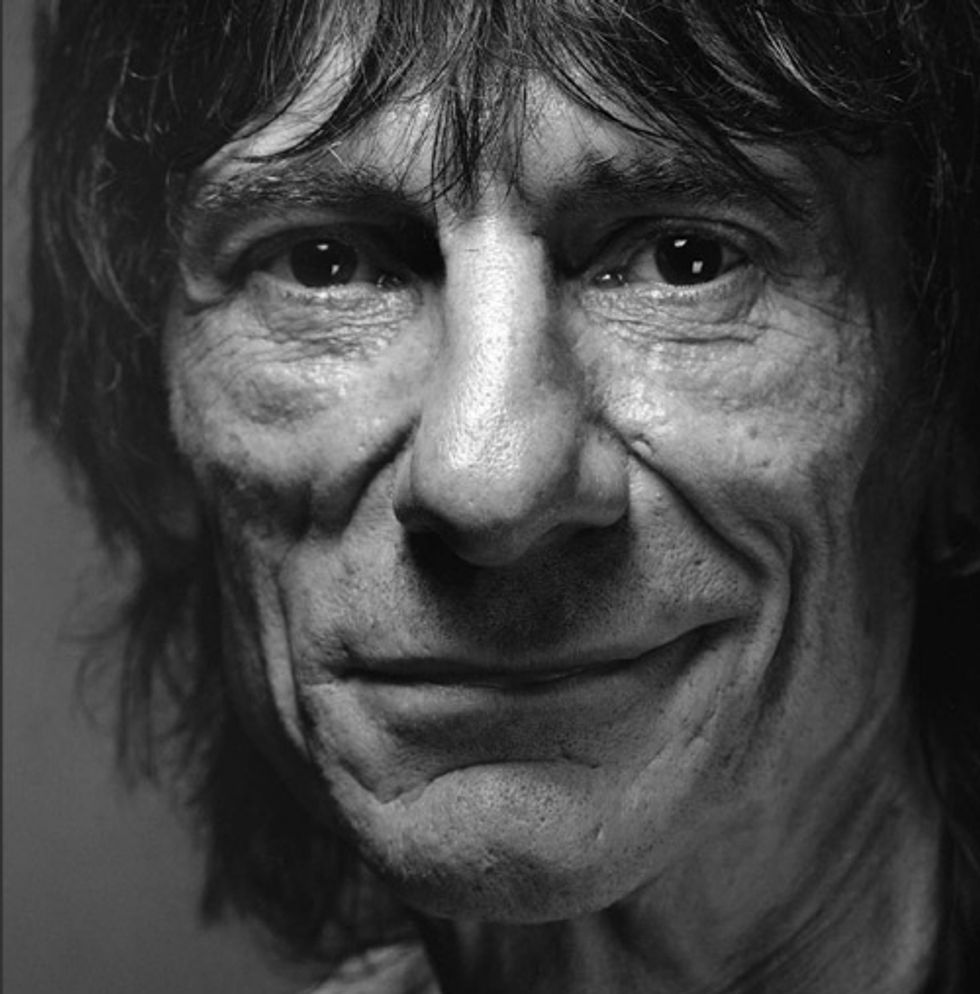

Photo by Jack English

Click here to watch video excerpts from this interview. |

And that was just the beginning of the seize fest. After changing trains a couple of times and getting yelled at by a very disturbed woman in Grand Central Terminal, we finally arrived at the unbelievably swank New York Palace Hotel. We were pretty early for our interview with Wood, which was scheduled for 2 p.m. So, we stowed our bags and took advantage of the intervening hours to briefly take in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Radio City Music Hall, vintage and boutique guitars at Rudy’s Music, and the best lamb gyro ever (only four bucks from a street vendor!).

But the whole time we were hyper-cognizant of how easily our trip could fall apart. We had to catch a 4 o’clock train to another event (see the Experience PRS story on p. 204), which meant there was pretty much zero wiggle room if Woods’ other interviews went long. We’d be left high and dry. So we made a point of getting back to the hotel an hour early, knowing full well that things can change on a dime when you’re dealing with a mega star.

And in this case, they did.

See, it seems we weren’t the only ones doing all the carpe diem-ing that day. It turned out Wood had been invited to lunch with Mick Jagger, President Bill Clinton, and President Obama. The two presidents were in town for the UN General Assembly, and apparently they’re big guitar nuts, too, so they rang up some pals. When we let Wood’s people know we were there, they said, “Good, we’ll send someone for you in 10 minutes.” We were the last group of journalists to talk to Wood before the afternoon’s interview schedule was pretty much obliterated by presidential order.

So we seized, baby, we seized. (Be sure to check out HD video excerpts at premierguitar. com.) You could say everyone there—us, the presidents, Jagger, Wood—was seizing the moment, really. But as we soon found out, that’s kind of been Wood’s MO his whole life. “I always try the impossible,” he told us. “Always think, ‘Yeah, I can do that.’ Nine times out of 10 it works.”

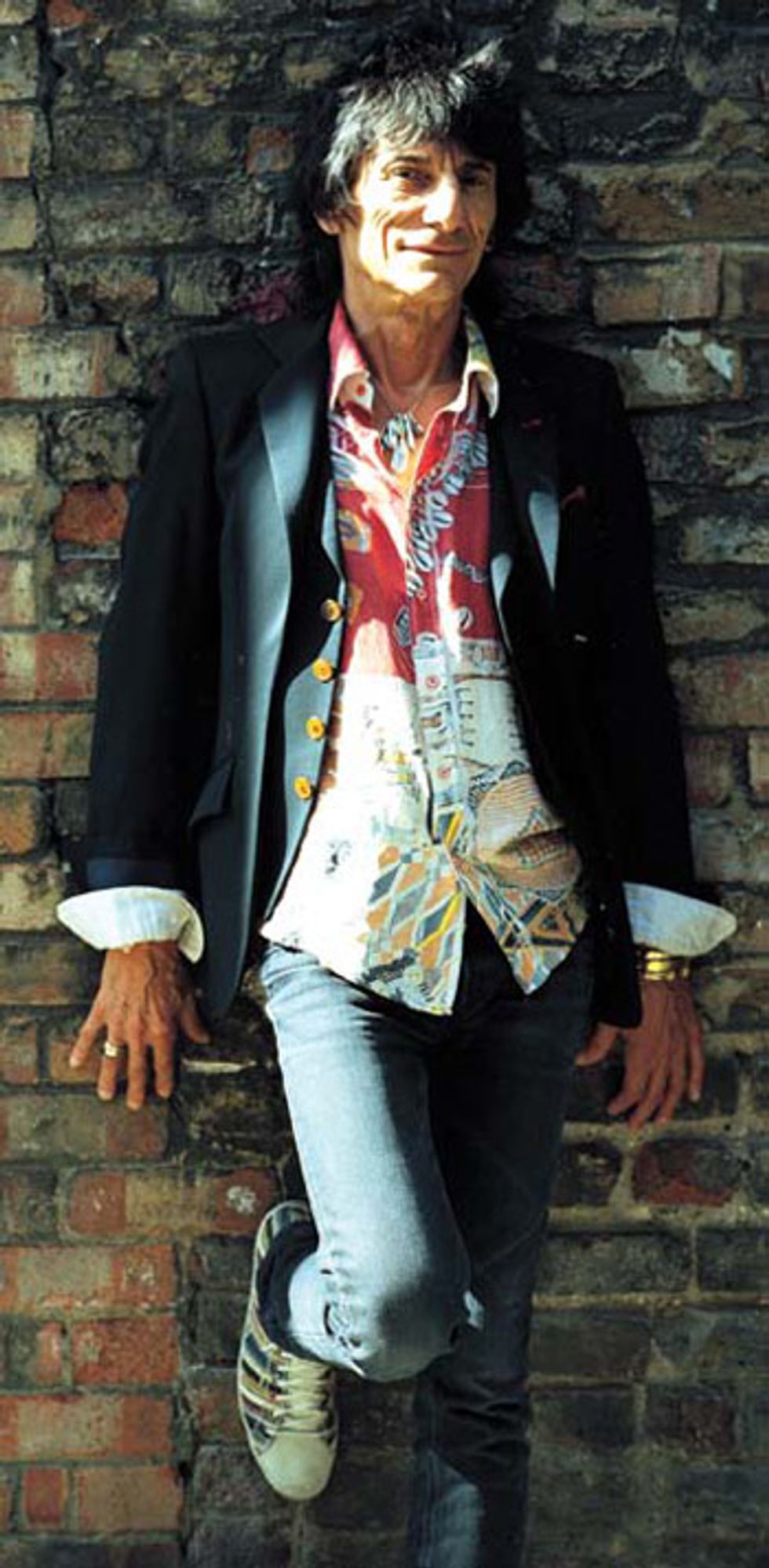

Indeed, at 63, Wood seems to be seizing more opportunities now than ever. An accomplished painter, he had just come from opening his own exhibit at the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio. He’s got his own line of clothes at UK-based Liberty department store. Just a few months ago he reunited with his former Faces bandmates and plans to tour with them next year. He took the stage with Eric Clapton, Buddy Guy, Jeff Beck, Derek Trucks, and John Mayer at the Crossroads Festival earlier this year. And his new album features guest spots by Billy Gibbons, Slash, Kris Kristofferson, Bobby Womack, and Eddie Vedder, among others. As if that weren’t enough, he’s working on plans to take I Feel Like Playing to Broadway with the cast of Britain’s Stomp dance troupe.

Despite being as giddy about his lunch date as we were to be in his 40th-floor corner suite, Wood was the complete gentleman as we discussed his favorite gear and what it was like to cut tracks with Slash and Gibbons—and not once did he rush the interview or act like he had to scram for more important company.

Ron Wood, Buddy Guy, and their dueling Strats paint a bloody good picture for the

crowd at last summer’s Crossroads Guitar Festival in Chicago. Photo by Chris Kies

How did the new album come about?

It was a natural chain of events, really. I left home, like you do, and I had songs like “A Thing Like That” and “I Don’t Think So” and lots of phrases going through my mind. I started the whole thing off with [billionaire real estate developer and film producer] Steve Bing. He said to me, “Hey, Ronnie, I wanna hear you play—people want to hear you play. I hope you don’t mind, but I booked the House of Blues tonight for you. I’ve got [famed session drummer] Jim Keltner out there, and I’ve got Ivan Neville.” And then I said, “Well, I’ve got Flea, he’s in town, and I’m here with [session vocalist/ Stones backup singer] Bernard Fowler.” So I said, “Come on, let’s all go to the studio, then, and make a start.” So, we started with “Spoonful,” a number that goes down through the years and that I was inspired by—I was inspired by Howlin’ Wolf. Willie Dixon wrote it. That was a nice suggestion from Bernard. He said, “Why don’t we start with that one, man. You could really do that.” So we did that in a couple of takes, just live. And it had a good feel about it. And then I said, “Well, I’ve got these ideas to put around these words, like ‘What do you want to go and do a thing like that for?’”—to be said in a Southern accent. I think it would make a great country and western song, actually. It should be played on a country station, with Kris Kristofferson writing the words to the verses. He was at the House of Blues, and I just happened to bump into him and Don Was on the steps going in. Kris showed an interest, and I said, “I’ve got this chorus—I need some words for the verses. Come on, Kris, write something for me, would ya?” And he said [assumes John Wayne-like drawl], “Okay, Ronnie. But I can’t do it today. Give me ’til tomorrow and I’ll come back with a couple of verses for you.” And he did, and I loved it. Y’know, “I hear that old coyote howlin’ at the moon,” and things like, “Liberty is all I ever wanted, holy fire is what I need.” Yeah, really typical Kris, and really helpful.

And [Pearl Jam vocalist] Eddie Vedder was the same way with helping me on “Lucky Man” and “Catch You.” It was great to get Bobby Womack back out of the woodwork, as well, to kind of help me with some backgrounds. He was pleased with my singing, and so was Rod Stewart. He came in at one time and he said, “Oh, you’re singing really well.” He said, “I give you the stamp of approval now—you are a vocalist.” And, coming from Rod, that was great—and Womack and Bernard. But, I had great people in the studios nearby, like Slash and Billy Gibbons, coming through. He [Gibbons] said, “I’ve got a song for you, man. [Sings] I’ve got a thing about you.” And Slash is always easy to work with. He says, “What do you want me to play?” I said, “You know— just go out there and play.” And we played together, and he knows what I want.

What a great story. You mentioned Slash, Billy Gibbons, Flea—and Bob Rock played on it, too—and one of the interesting things when I listen to the album is that, on a lot of albums with star-studded lineups, you can really pick out the famous player because what they’re playing sounds like it’s coming from one of their own projects. But on this album, everyone really blends in.

Yeah, I sometimes don’t know which is me playing or which is Billy Gibbons or which is Slash. The great thing is, we have an understanding that it’s a front room, very casual kind of feel. It’s not like, “Okay, you’re featured here.” No, none of that. It’s just very natural.

It’s like everyone surrendered their egos and just contributed to the music.

I’ve always done my solo albums like that. There’s always been a very mutual understanding, and everyone’s just kind of, like you say, they drop whatever egos they have. Normally, I don’t work with people with egos . . .

And I don’t mean it in that way—but it’s just so cool because you listen to a track and you’re not thinking, “Oh, that’s Billy Gibbons right there,” because it’s got that Texas boogie groove.

On that song “Thing About You,” I don’t know which part he’s playing. The only bit that gives him away is when he goes doooooo. You know that’s him, his little signature.

Did you approach writing and recording for this album differently than you would for a Stones record?

Yeah. On a Stones album, for a start, you have to get it passed by “the board,” y’know. Jagger and Richards don’t accept a suggestion very easily, because they’ve already got it sewn up. So you’ve got to have a pretty good song to get it by the board—which I respect. And, in Stones downtime, we all pursue our own thing. Whether Mick does a film or Keith’s doing his pirate or making an album. Charlie’s got his jazz outfits or quintet or quartet or whatever—an orchestra. He has to keep his chops together. He loves to play. That’s what I love to do, I just love to keep playing. Y’know, keeping my fingers hard at the end—otherwise, you give it a few months and they start to go soft. It’s no good. You’ve got to keep working. Keep painting and keep playing.

Mick Jagger struts his stuff and Wood plies his trade on a Gibson Les Paul

Special during the Stones’ August 10, 1994, Voodoo Lounge tour date at the RCA

Dome in Indianapolis, Indiana. Photo by Ken Settle

Other than getting to call all the shots and make the decisions yourself . . .

Yeah, that’s a good exercise, you know?

But stylistically or as far as how you approach writing your parts, is it any different from how you might do it with the Stones?

Not really. I always give my best and I’m always very natural with it. It’s kind of easier [because] it’s laid on the plate by the Stones more. Mick or Keith will have this riff and I interpret it immediately. “Oh, I know what you need.” And they know that. With my albums, I often know what the basis is, and I know where I want to take it—and that’s why I can have guests on it. Because if they don’t play it, I’ll play it anyway. So it’s just a matter of party time—it’s like, “Okay, let’s party. Let’s have some fun making a record.” That’s what I love to do.

How do you approach getting the actual guitar tones?

[U2 guitarist] Edge said to me, “How do you get that tone?” And I said, “Just turning it up to 10 and hitting the full volume.” [Laughs.] I don’t use effects . . . very rarely. And he’s Mr. Effects, and he can’t understand how to do it.

Did you use the same guitars and amps you would normally use with the Stones in the studio?

Yeah. My man Dave Rouse, my guitar roadie, he said, “Do you want the Champ, Ronnie? Do you want the Deluxe or the Twin?” I usually go with a Strat with a whammy bar, or a slide, or a B-Bender. I didn’t use a B-Bender on this album, which I would have liked to have done—but I did use a pedal steel, so that’s even better.

Do you remember which particular guitars and amps you used the most?

Not really, but I suppose my old standby is my ’55 Strat and a Champ amp. “Have guitar and amp, will travel!” [Laughs.]

What’s the year on the amp, roughly?

It’s a tweed from the ’50s.

Do you feel like your concept of what constitutes good guitar tone has changed over the years?

Well, I think, like wine, the matured sound of a ’50s Strat is more or less a stable part of my diet—like with Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page and Eric Clapton. They’re just very comfortable. You get that reliable sound that comes from a ’50s amp and a ’50s guitar, whether it’s an acoustic or an electric. Y’know, you go to a Martin for an acoustic—or an old J-200. But some of the new guitars that are available, they’ve got a bloody good sound.

Did you use any other amps or guitars besides the Strat and the Champ?

Well, yeah, I’m always open to ideas. I mean, I’ll use a Les Paul once in awhile. But that’s another thing—if you’ve got Slash around, you know you’re going to have a Les Paul sound. So, I’ve got the Fender side covered. But, amps-wise, a Boogie or an old Vox AC30. They’re all there if I want to use them.

Is the Boogie an old Mark IIC or something?

Just the regular Mesa/Boogie with the EQ on the front. I don’t know the model name.

An older one—the little combo?

Yeah, they’re cool. As far as different amps, I used an old Fenton Weill on the solo for “Maggie May.” It was like, more or less, a converted radio—it’s a bit like the Champ amp is. There’s a bit of distortion already built in, just because of the old valves and stuff.

Keith Richards (right) wields a then-recent Tele while Wood rocks

a trusty Strat on February 22, 1999, at the Stones’ No Security tour stop at the Palace

of Auburn Hills in Michigan. Photo by Ken Settle

So, even though it sounds like you’re really hooked on old classic gear, do you ever try out new boutique stuff? There are so many companies trying to recapture the old handwired amp sound.

And they do a damn good job. Sometimes I can’t tell the difference between a valve amp and a modern job, y’know. But, you just put it to the test. I mean, if it can survive a tour—a heavy beating on a tour—then it’s the sign of a good amp.

Off the top of your head, what were some of the highlights of the sessions with these big-name guitarists? Let’s start with Billy Gibbons.

Well, Billy Gibbons is very bossy for a start. He went like, “We’ve got this riff, right.” [Sings short ascending lick.] And I’d go [sings descending melody]. “No, not that! No, just play the lick. Play that.” And I’d go, “Okay, Billy.” So we’d play that together. And then when it comes time to let it rip, he’d go, “You take it your way and I’ll take it mine, and I’ll meet you in the middle.” He was just great fun, and he’s a very enthusiastic, creative person. And I love to bounce off that creativity.

And he played on two songs right?

Yeah. When we finished “Thing About You,” I said, “Oh, I’m working on this other song called ‘I Gotta See.’ How about I play it to you.” And when he heard it he went, “Oh! [Sings rhythm line.] It needs that kind of approach.” I said, “Yeah, perfect! Go for it.” He just did that in one take.

How about the most memorable moments with Slash?

Well, every time he’s there, he’s always in the same mood. He’s never upset. He’s never over-the-top happy or sad. He’s always like [in quiet, ultra-laidback voice], “Hey, awesome, man.” He’s like, “Hey, man, I really enjoyed that.” That’s the most he ever gets worked up, like, “Hey, that’s really good, man.” I just had him on my radio show. We filmed that, as well, when he was in the studio for this program for Absolute [UK radio station Absolute Classic Rock], which is really great. We do 52 programs, one for each week of the year. I go through archive stuff. I play everything from the first rock ’n’ roll song right through a bit of Mozart, bit of Marley, and up to people like Regina Spektor and a little of what’s happening now. It’s a great exercise for me, and it is a very educational program.

How about Flea? He’s obviously a monster bass player, and half the bass-playing kids in the world worship him, but on the songs he’s on he’s just rock-solid—no showing off whatsoever.

I just like to let him take it his way. I didn’t have to tell him what to play. I was just happy to see that he was happy with his groove, and it was great to see him working with someone like Keltner. They really got along well. And then you would get people like [longtime Stones bassist] Darryl Jones juxtaposed against people like [session drummer] Steve Ferrone. There were some nice, interesting things happening. And [bassist] Rick Rosas, you know, he’s a good old solid from the Neil Young days. Good people. Good teamwork.

Bob Rock also played on two songs, and he’s known for his production work with huge bands like Metallica. What was it like having him on there?

He’s a real gentleman, and he’s a real fan. I didn’t realize he grew up listening to what I played, y’know, when he was in short pants. He knows more about what I did than I do. [Laughs.] It was great to work with him being a fan and a creative person. And he was only too happy to say, “Ronnie, I’ve got these songs [Rock co-wrote “Lucky Man” and “Catch You”]. I’d love to hear the way you would interpret them.”

As a musician, as a guitarist, and as an artist you’ve conquered the creative world several times over.

I’m not finished yet—you’ve gotta be ambitious. [Laughs.]

What motivates you to pick up a guitar these days?

Love, ambition.

Is playing guitar in a band different now from how it was 30 years ago?

No, except I’m that much older now. I’m a bit wiser. But some of the things don’t work like they used to—I tore the arse out of ’em years ago. [Laughs.] But I’m lucky to still be alive, I suppose, to have survived everything. I’m really grateful. I’m a lucky man.

|

Not often enough. I have guitars sitting around—I’ve got them all in my room now, for instance. I might pick it up in passing and just play a little lick and walk on, because I’m always so busy. I get in these modes. I’ll get in an art mode, and then I have to keep painting. And then I get in a musical mode, and that’s when I keep playing. Luckily, these moods and these shifts of inspiration come at the right time to keep me off the street. Y’know, to keep me satisfied. [Laughs.]

Before the interview, we tweeted our readers and viewers inquiring what they wanted us to ask you, and some wanted to know how your painting informs your guitar playing—or vice versa.

Well, sometimes I play to a painting and sometimes I paint to music. They’re so closely related, because when you’re doing a painting, it’s like overdubbing. You know, you put the backing track there, and then you come through with the guitars, and the final vocal, and stuff. It’s just like the layers of tracks in the studio.

Do you get into a rhythm that affects your brushstrokes when you’re painting to music?

Yeah, I get into a rhythm when I’m painting. This is pure expressionism.

Which musicians or artists are inspiring you right now?

Very few, actually. There’s this girl singer, Russian girl, called Regina Spektor. She’s very simple, but very classical. She’s coming to London in October, actually, and I got in touch with her record company and I said, “Can I do something with her,” something musically. I’ve never actually met the girl and I don’t really know what she looks like or anything, but I just like the way she sings.

Is that in the works?

No, but I’m going to hijack her when she comes to England.

You’re going to harass her until she says yes.

Yeah, I’m going to say, “Come on, let’s do something together.” She might say, “Sod off.” I don’t know. But that’s the way I always work. I approach the unapproachable. I go up to Bob Dylan and say, “Come on, let’s play.” Everybody. I’ve done that with Bob Marley. With Zeppelin. I just go and play with them.

You never get anywhere unless you try, right?

Exactly, and most of the time all of these unapproachable things or people turn out to be really down to earth. Like Prince. His band members are the nicest bunch of guys in the world. He’s hard to get through to, but when you’re actually playing with him, he’s like a humorous, really down-to-earth, clever guy.

Robert Plant was recently interviewed on NPR, and he was talking about being a kid and listening to James Brown and Smokey Robinson on American radio stations, and then saving up money from his newspaper delivery job to buy albums from King Records in Cincinnati. Do you have a similar memory of when you were first hooked on music?

Yeah, I remember when I was a kid in short pants or I had just gotten out of short trousers. I had a little record player in my room and I was playing Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Fats Domino, Muddy Waters, and Howlin’ Wolf —all that kind of thing—and I was thinking, “I’m going to meet these guys one day. I’m going to play with them.” And I did. Every one of them. Bo Diddley turned out to be one of my greatest pals.

How old were you at that point?

I was 14 or something. Before then, I was listening to Big Bill Broonzy at about the age of 7 or 9, and playing guitar shuffles and stuff.

At what point did you think, “I’m going to do this for the rest of my life”?

Oh, ever since I picked up a guitar. And ever since I picked up a brush. I knew I was going to do it. Right from an early age. From 4— my earliest memories.

If there were one bit of wisdom you could distill for the average guitar player to take to heart, what would it be?

Well, I always go in the deep end. I always try the impossible. Never think that something is too much of a challenge. Never think, “Oh, I’m not going to do that—I wouldn’t be right for it.” Always think, “Yeah, I can do that.” Nine times out of 10 it works. I have done that all my life. When I was at school, I knew I was going to be in the Stones. I knew I was going to be in that band, no two ways about it. So, here I am 35 years later, and still the new boy. [Laughs.]

Wood and I discuss his latest album, I Feel Like Playing, at the New

York Palace Hotel on September 23, 2010. Photo by Joe Coffey

You announced in May there would be a Faces reunion tour.

Yeah, we did that with [Simply Red singer] Mick Hucknall. He sang like Rod [Stewart] did in the ’70s—he was incredible. We only did three shows, because Mick’s out with Simply Red, putting that band to bed now.

But there was also something about a tour next year, right?

Yeah, probably in January we will come over here.

And will that also be with . . .

That will be with Mick Hucknall. But I’m having dinner with Rod Stewart next week. The whole thing has his blessing, and he likes the way that Mick is very respectful of his singing—and the other way around. If it weren’t for Rod’s red tape and his management, we’d have him doing it. But Rod also self-admits that he can’t sing in those keys anymore, like in the early ’70s. Mick Hucknall can, but even after the three shows, Mick went, “My god, I don’t know how Rod kept this up for all those years. My voice is in shreds!” Because we did them all in the original keys. “Too Bad” and “Miss Judy’s Farm” and “Pool Hall Richard” and “Stay with Me.” Mick would say to me, “That’s so high to sing!”

You’re doing quite a bit of publicity for your new album, I Feel Like Playing . . .

And the President of the United States calls! [Laughs.]

And they will be here any minute.

That’s gonna be fun!

You’re just hobnobbing with so many . . . well, I guess that’s your life, right?

Oh, man. There you go—there you go, kids: You can end up in the president’s company if you want! [Laughs.]

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)