However many fancy gizmos the techs

devise to give us “warm, tube-like" guitar

sounds, real tonehounds know it's only happening

in one place: real tubes! If you want

to get it happening for you, though, you've

got to understand what's going on with different

tube types, and learn the various ways

the wide range of tubes available will affect

your sound. (Click here to read part one: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Preamp Tubes.)

In the last issue I discussed preamp tubes, along with a basic primer on how and why tubes do what they do. This trip under the hood we'll explore output tubes—the big bottles at the back of your amp that pump out the serious wattage. Although some people refer to them as "power" tubes, I feel "output" is far more fitting: for one thing, these tubes create your amp's output; for another, the term "power" might cause confusion with the third type of tube in an amp—a rectifier tube—which lives in what is correctly described as the power stage of the amplifier. In any case, you mainly just need to be aware that the output tubes are the "amplifier within your amp": while the preamp tubes ramp up the signal from the guitar, the output tubes are the babies that really make it loud.

Output tubes can be recognized as the biggest, or at least tallest, tubes in the back of your amp, although a tube rectifier (if your amp has one) can also be mistaken for one of several output tube types. Your clue here will be that there's usually only one rectifier, but at least two matching or similar output tubes in any amp, other than small single-ended "practice" amps such as a Fender Champ or a Gibson GA-5. Many, many types of output tubes were used in the glory days of thermionic devices, when they appeared not only in guitar amplifiers, but in radios, stereos, TVs, and many other applications. Today, only about half a dozen varieties of output tubes are regularly used by contemporary amp manufacturers, and just four of these are seen in any great numbers. The four most common output tube types are the 6L6GC, 6V6GT, EL34, and EL84. A handful of contemporary makers still offer amps with KT66 and 6550 tubes, and a few even manufacture unusual designs using more esoteric tube types, but you'll see one of those first four in a good ninety-nine percent of amps you encounter today.

Other than EL84s, which are the same diameter as preamp tubes (although taller) and use the same 9-pin socket, all of the most common output tube types use large 8-pin (octal) sockets. While they might appear interchangeable in terms of socket size, however, most have different circuit, voltage, and bias requirements, so they cannot simply be substituted one for the other in most amps. There are a few makers today producing amps that are specifically designed to let you swap between output tube varieties for "tube tasting," and models such as THD's UniValve and BiValve, and Victoria's Regal II and Two Stroke can take any of the common 8-pin types without needing rebiasing or other adjustment. For the most part, though, a maker will design an amp with a very specific tube type in mind, and will work very specifically to the performance and sonic characteristics of that tube. Let's take a little look at the signature tones and capabilities of some of these more common output tube types.

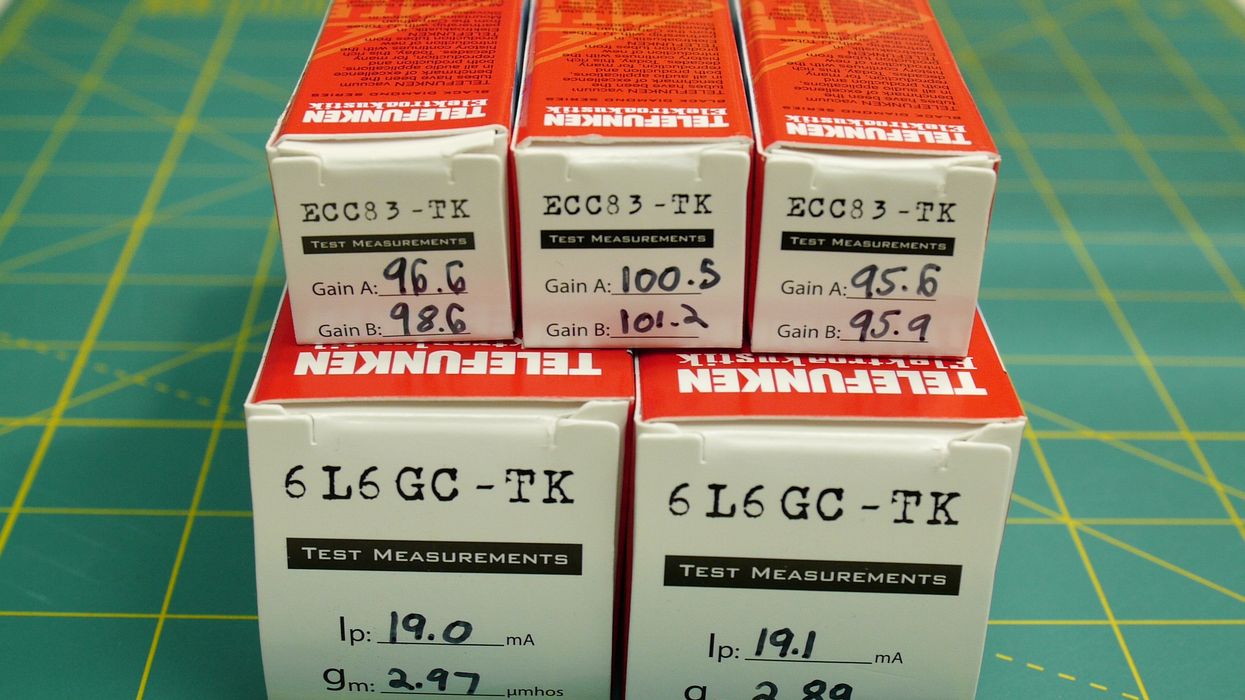

6L6GC

photos courtesy of thetubestore.com

Think "big Fender amp tone" and you're thinking 6L6 (also sometimes substituted for the interchangeable 5881, essentially a ruggedized 6L6). This is the big-amp output tube traditionally seen in American-made amplifiers, and it has a bold, solid voice with firm lows and prominent highs, which can be strident in loud, clean amps, or more silky and rounded in softer, "tweed" style amps. A pair of these will generate around forty to fifty watts in an efficient Class AB amp; a quartet (with two pairs working in teams on each side of the phase-inverted signal) can put out up to one hundred watts. In less efficient, but juicily toneful, cathode-biased designs (socalled "Class A" amps) like TopHat's Super Deluxe or Carr's Rambler, or a mid-fifties tweed Fender 5E5 Pro, a pair of 6L6s will put out around twenty-five to thirty watts. This is the tube of anything from the Fender tweed Bassman and blackface Twin and Super Reverbs, to early Marshall JTM45 heads and "Bluesbreaker" combos, to the Mesa/Boogie Mark Series and beyond.

6V6GT

photos courtesy of thetubestore.com

Think small-tweed amp and you're hearing the 6V6GT. Smaller American-made amps of the nineteen-fifties, sixties and seventies most often carried 6V6 tubes, which are known for their juicy, well-rounded tone and smooth, rich distortion, which occasionally exhibits an element of grittiness that is not necessarily unappealing. They produce about half the output of their big brother, the 6L6, and are therefore more easily driven into distortion. The 6V6 was used in many Fender designs—the Champ, Princeton, and Deluxe lines among them— some great vintage Gibson amps like the GA-40 Les Paul Amp of the nineteen-fifties and early sixties, and countless others. From the late eighties to late nineties no reliable current-manufacture 6V6s were available, so few manufactures designed new amps around this tube. This is the course of events that led to the virtually unthinkable release of smaller Fender amps that used EL84s, such as the Blues Junior (the early-sixties Tremolux, which briefly carried EL84s, being something of an anomaly). The release of a rugged and reliable 6V6 first from Electro-Harmonix, then from other contemporary makers, has led to a renewed popularity for this tube, and it proliferates again in the twenty-watt-and-under range.

EL34

photos courtesy of thetubestore.com

Take your aural imagination across the pond, conjure up that big, British crunch tone, and your mind's ear is hearing the EL34. The classic Marshall tube, the EL34 was the big boy of British amplification from the late nineteen-sixties onward. It can be driven at higher voltages to produce a little more output than the 6L6GC, and it sounds somewhat different, too: characterized by a fat and juicy but softer low end, sizzling highs, and a midrange that exhibits a classic crispy-crunchy tone when driven into distortion. This is the tube of post-1967 Marshalls like the JMP50 "plexi" and "metal" panel amps, the JCM800, and the majority of modern models. It also appears in the classic Hiwatt models, and plenty of modern amps seeking a big Brit-rock sound. Many contemporary American makers, such as Rivera and VHT, have also used EL34s for high-gain amp designs, and plenty of boutique makers also employ this output tube.

EL84

Sometimes described as "a baby EL34" because it is another classic British output tube, the EL84 really has a tone all its own. This tall, narrow, 9-pin output tube is best known for its appearance in classic Vox amps such as the AC15 and AC30, and is most often used in "Class A" circuits, which seek to achieve a sweeter, more harmonically saturated sound at the expense of a little output efficiency. The EL84 can still exhibit a pretty firm, chunky low end in the right amp, but is most known for its chimey, sparkling highs and a midrange that is crunchy and aggressive when pushed. A pair in a cathode-biased output stage (a la Vox) will put out around fifteen to eighteen watts, and a quartet double that. These tubes also appear in many modern amps that emulate the "Class A tone," including models from Matchless, TopHat, Dr Z and others.

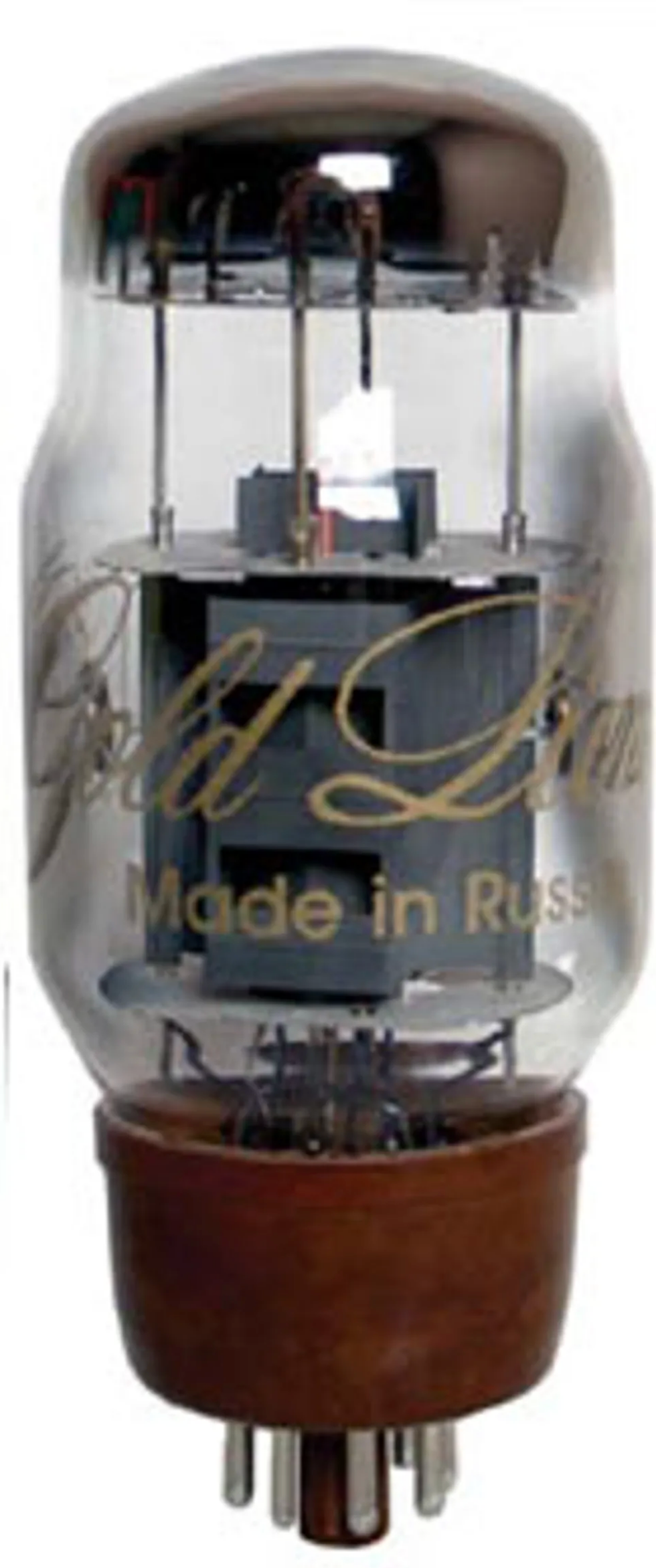

KT66

Rarely seen for many years other than in vintage amps that carried them (notably early-sixties Marshall JTM45s, following their brief use of 5881/6L6s originally), the KT66 (pictured at right) is a direct substitute for the 6L6, but really has a character all its own. This tube of European origin is a little bolder, firmer, and fatter than its American cousin, and can put out a little more volume. A few good recent reissues of this tube type have led some amp makers to design around it again, and Dr Z's Route 66 is one example of a popular boutique amp that takes advantage of the KT66's potential.

6550

Marshall amps exported to the USA from around the mid-seventies to the mideighties were modified to use 6550 output tubes instead of the EL34s they were originally designed for, apparently for reasons of availability and reliability. The change altered their character somewhat, as the 6550 doesn't sound especially like an EL34, but more like a bigger, louder 6L6 (in approximate terms). That's not to say it's a bad thing, just different. Many other makers have designed amps around this lesser-seen output tube, such as Alessandro and ENGL. The 6550 is perhaps more commonly seen as an output tube in big bass amps, and was used for a time in Ampeg's SVT, and currently appears in models by Traynor and others.

While each of these output tube types has its own characteristic tone, different makes of tubes of the same type can sound quite different, too. Take six different pairs of 6L6GCs from different manufacturers, for example, some old and some new, and each will sound just a little different in your amp (sometimes a lot different). Tube connoisseurs rave about NOS tubes (new old stock), meaning tubes that were manufactured in the USA or Europe many years ago, but have never been used—and certainly these can represent the pinnacle of output tube quality, provided you can find a good, tested pair that is genuinely NOS and not just used, pulled from an old hi-fi, and polished up a little. You'll hear tubeheads go all gooey over black-plate RCA 6L6s, Mullard EL84s, Brimar 6V6GTs, GEC KT66s and many other types that carry the great brand names of old, and certainly there's a lot to be said for them. Any pair you can find in genuinely good condition, tested, and guaranteed will also be very expensive these days. Grab some if you can (and certainly if you find some going cheap from an old supplier who is selling out; but also be aware of fakes and forgeries being sold online these days as NOS—there are plenty of them around). But there are also many, many excellent current-manufacture tubes today that are very good—with better quality and better selection than was available even ten years ago—and these exhibit different sonic characteristics too. Read about their respective pros and cons online (there isn't room to go into full detail here), or try a few different pairs of the types that seem like they'll suit you, and see how they change the sound of your amp. When you locate a pair that's just right, you can always keep the others for back up.

As discussed briefly in Part 1, distortion occurs in all stages of a tube amp, but the resultant overdrive tones sound a little different depending on which type of distortion is generated where. Preamp tube distortion, as much fun as it can be, will sound a little more fizzy and gritty, while output tube distortion will sound comparatively thick, rich, and dynamic (in broad terms). Old-school tone freaks tend to enjoy the distortion tones generated at the output stage, which is why you see many such players going for vintage—or vintage-styled—amps with simple circuits, no master volume (or one that's bypassable), and a minimum of bells and whistles such as channel switching and added gain stages. Such amps aim to drive the output tubes more than the preamp tubes, and to generate that creamy, harmonically saturated overdrive tone when cranked up. This love of output-tube distortion is also what's leading a lot of players, touring pros included, to use smaller amps on stage. Few players really need a big double-stack to be heard on stage these days, and it's harder to push such amps into overdrive without incurring the wrath of the soundman and blowing your band mates off the stage. Use a smaller fifteen to thirty watt combo or mini-stack, however, and you can hit the sweet spot and still (hopefully) dodge the tinnitus until well into late-middle age.

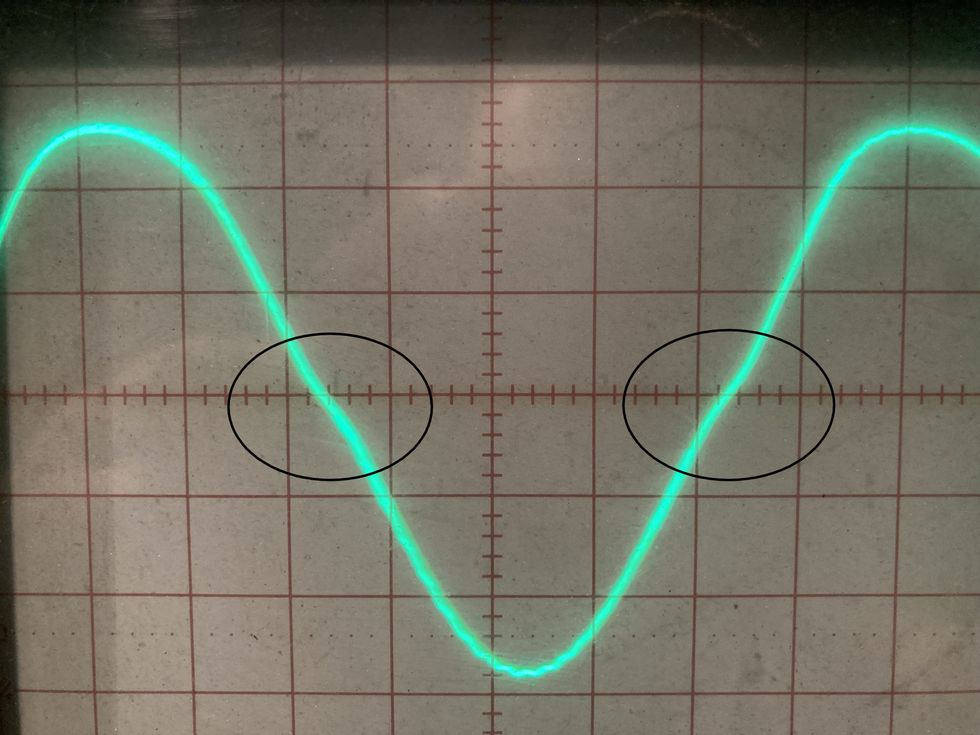

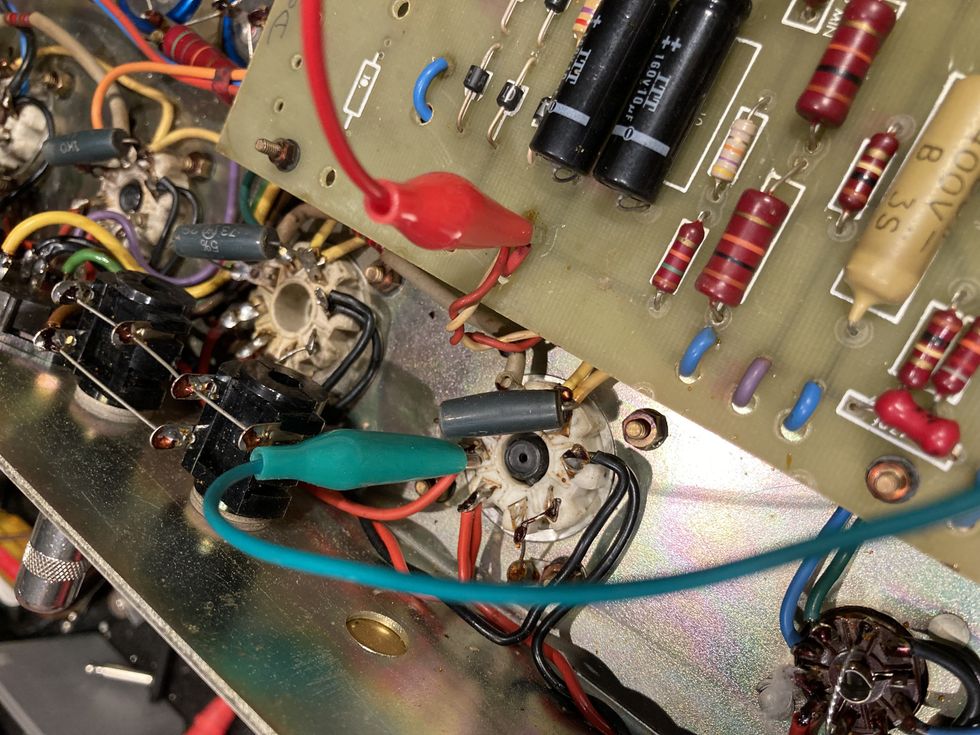

Be aware that many types of amps also need to be rebiased when output tubes are changed. This is something you can do yourself with the help of a kit (several types are available), or have done for you by a qualified tech for a nominal charge. An amp's bias is like a car's idle speed: it needs to be set correctly for the amp to operate efficiently, and an incorrect bias setting will also seriously impede your tone. Confusingly enough, "fixed bias" amps are the ones that generally have adjustable bias levels that need to be checked and reset when you change tubes. Cathode-biased amps, on the other hand, which are often billed as "Class A amps," have a bias level that is set at the factory with a fixed resistor. With these, you just pop in a good, matched pair of new tubes and away you go.

It's also worth knowing that any new set of output tubes, whether NOS or new manufacture, will need some playing-in time. They won't sound their best until you have put a few hours on them, and maybe as many as forty or eighty hours of playing time to get them into the tone zone. Not unlike a vintage bottle of wine, output tubes need to "breathe" a little before they will be at their peak. Similarly, once you uncork that prized NOS pair that has rested on the shelf for three decades and start playing them, they won't last forever. Hopefully the tonal payoff will live up to the anticipation. Test, taste, sample, enjoy—there's gold in them thar tubes!

[Updated 9/1/21]