Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Understand how root-fifth shapes can alter basic harmony.

• Create more interesting guitar parts by layering different sounds.

• Learn how to imply more complex tonalities with standard power chords.

Click here to download MP3s and a printable PDF of this lesson\u2019s notation.

Chords that contain only a root and 5, which everyone knows by the moniker “power chords,” are an essential part of the arsenal of every modern guitarist, especially in rock, pop, metal, and even country. A power chord is just a triad without the 3. Lacking a 3 or b3, power chords are neither major nor minor, and it’s this absence that lends the chord its utility because the ambiguous power chord can stand in for the triad built on almost any root within a key or outside of it. Unfortunately, this same characteristic can make compositions made up only of power chords sound stale and less than complete.

But with a little music theory exploration (and a guitar buddy), power-chord rhythms can take on a very hip, multidimensional character. You just need to add a second guitar part. It’s easier than you might think, and keeping it simple is the key. In each of these six exercises, you’ll master a familiar root progression and easy secondary riff, which unite to form rich, complex tensions. The progression will employ a combination of open-position root-fifth grips and the familiar, three-finger power-chord shapes. We’ll also probe the theory that makes each progression work. So grab your axe, fire up the tubes, and let’s jam.

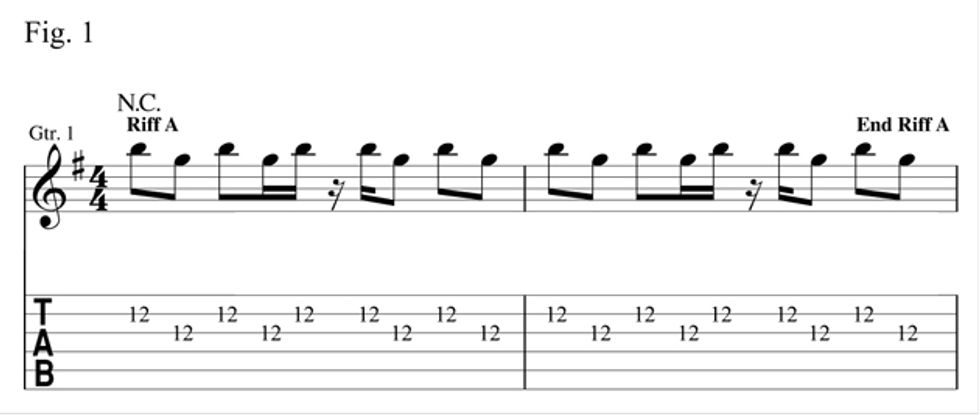

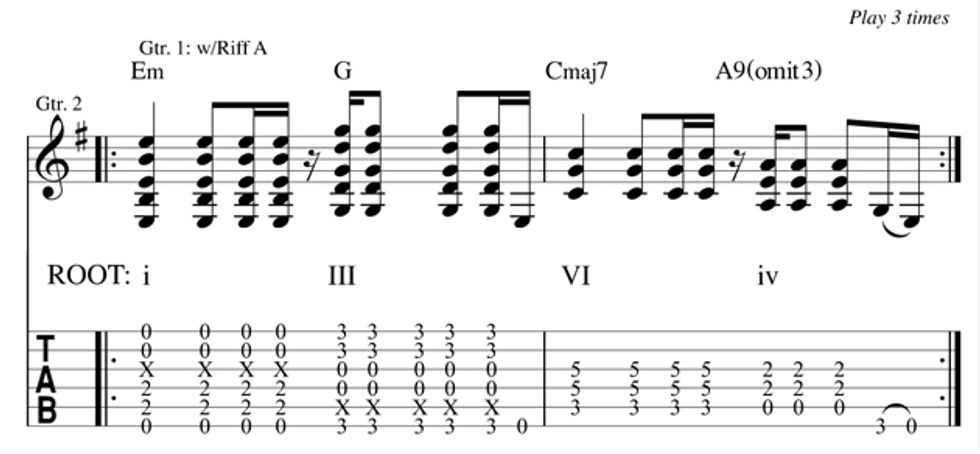

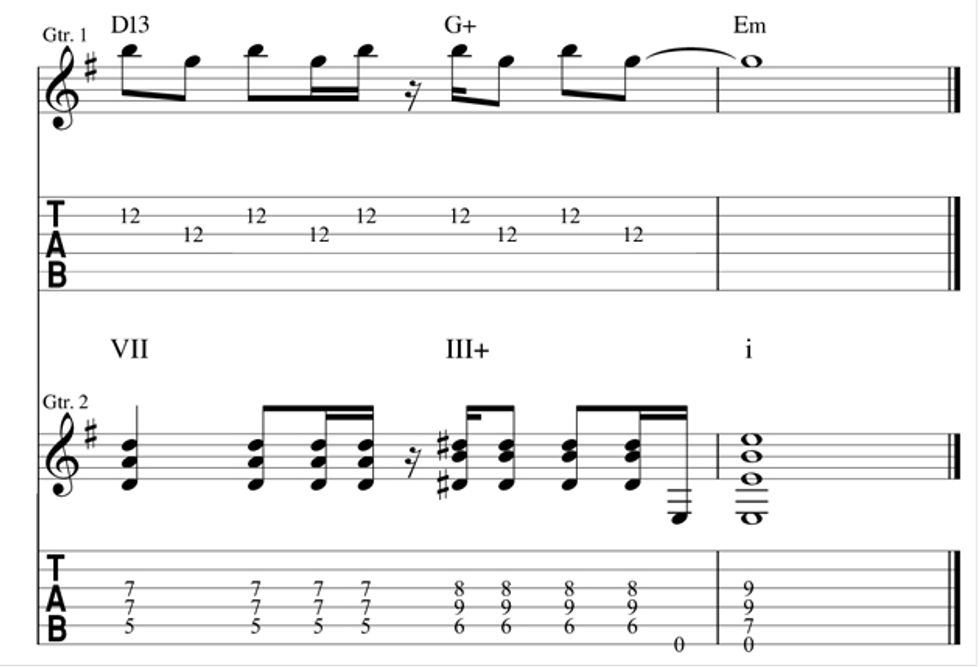

Fig. 1 is a repeated Im–III–VI–IVm progression, finished off by a VII–III–Im in E minor (when the rhythm guitar comes in, follow the root progression indications between the staves).

In the right channel is a simple riff consisting only of the notes G and B in the 12th position— scale degrees 3 and 5 of the key. On the Im chord, E5 combines with G and B in the riff to form a full Em triad voicing. Next, the G5 is transformed to a G triad due to the B, and then it gets a little tense. The addition of B to the C5 chord gives a very bright Cmaj7 voicing. In a similar way, B and G create major 9 (B) and minor 7 (G) sounds over the A5 chord.

In a nifty turn at the end, G and B suggest a full dominant 13 chord when played over D5. And finally, while the rhythm guitar plays what is actually a V chord (B/D#), the G in the riff changes the character of that chord completely, morphing it into a G augmented triad, before heading back to Em.

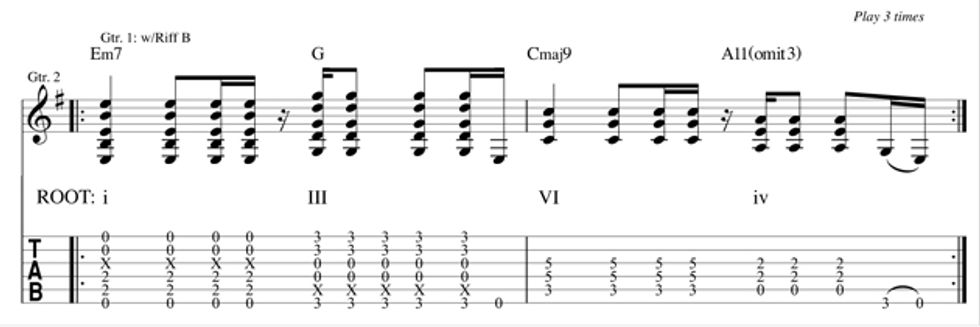

In Fig. 2, we have the exact same rhythm part, but the lead riff has been altered to accommodate D, which is the 7th tone in E minor. Listen to the changes again and hear how the addition of just one note makes the harmonies fuller, adding extra tensions over what we achieved in Fig. 1. Now you have a full Em7 chord for Im, a full Cmaj9 for VI, and over the A5 chord, you have a 7, a 9, and an 11.

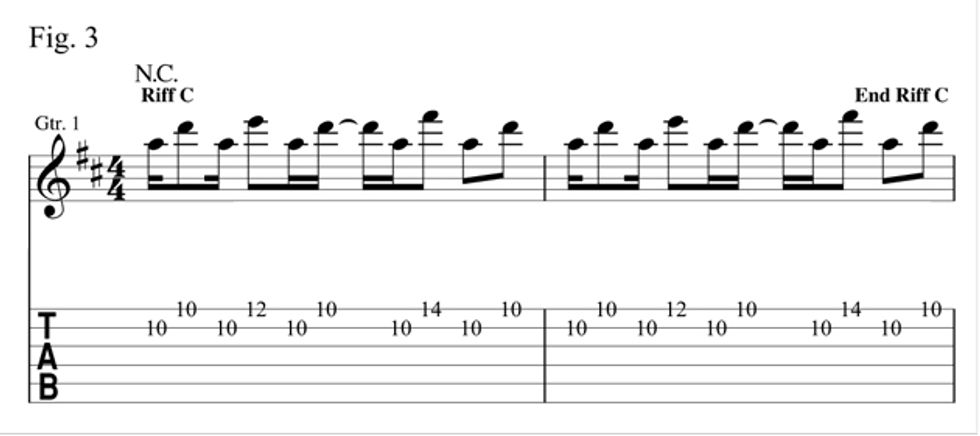

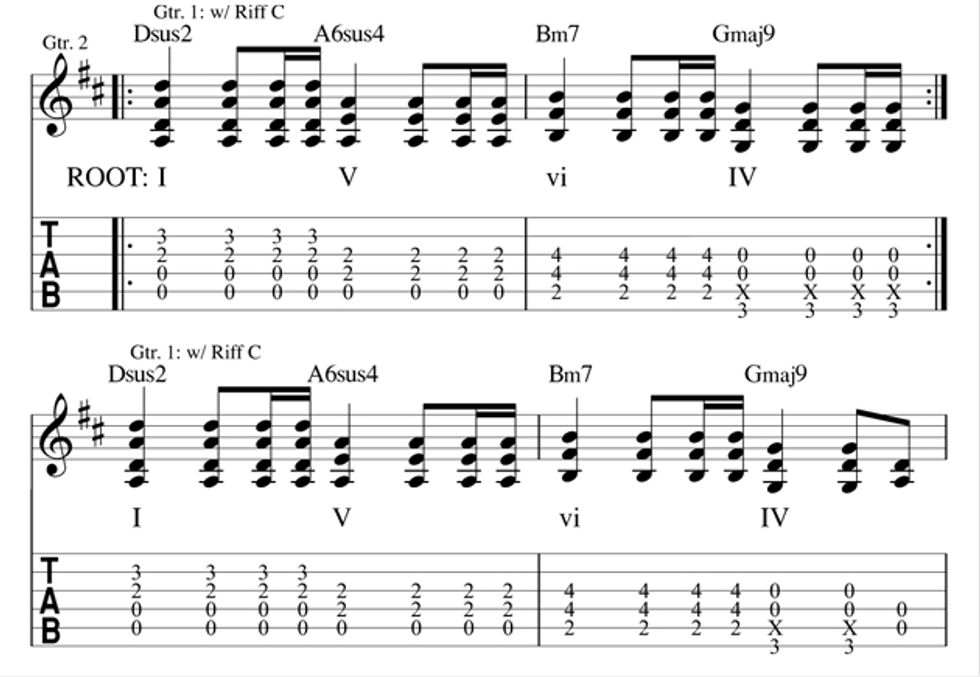

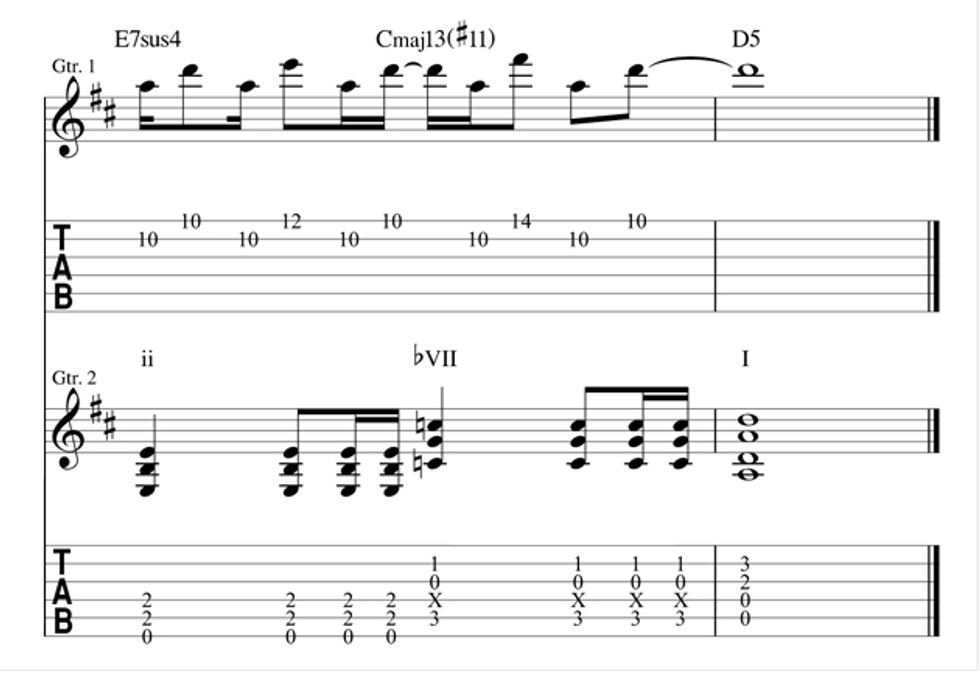

Now, check out Fig. 3. Here, we have repeated I–V–VIm–IV, capped off by a turn of IIm-bVII–I in D major. The lead riff plays around with the 5, root, and 2 of the key in the first half of each measure, and the 5, root, and 3 in the second half. This provides plenty of notes to fill out the harmony on those changes.

The E in the first part of the riff combines with D5 to give us a Dsus2 chord. But pay attention to that A5 chord: D and F# tag-team to make it into a bright and colorful A6sus4. Then, it’s A and D’s turn to make ordinary B5 into a Bm7 chord, followed by F# and A from the riff to give us Gmaj9 instead of just G5. In the second-to-last-measure, E5 is converted to E7sus4 (which you can also think of as an Em11), courtesy of the notes A and D. And for one ear-bending moment before the final chord, C5 gets a facelift vis-à-vis the notes A and F#, sounding a very spacey Cmaj13(#11).

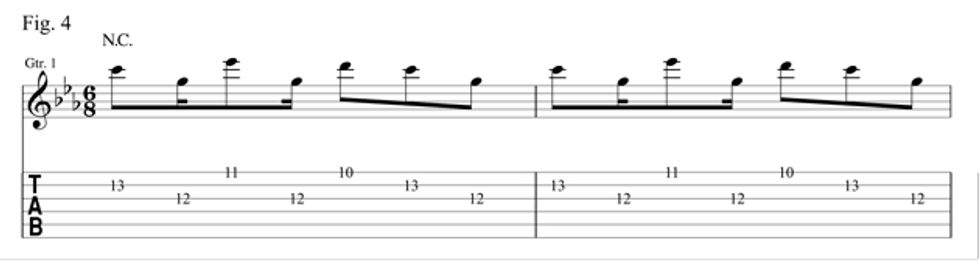

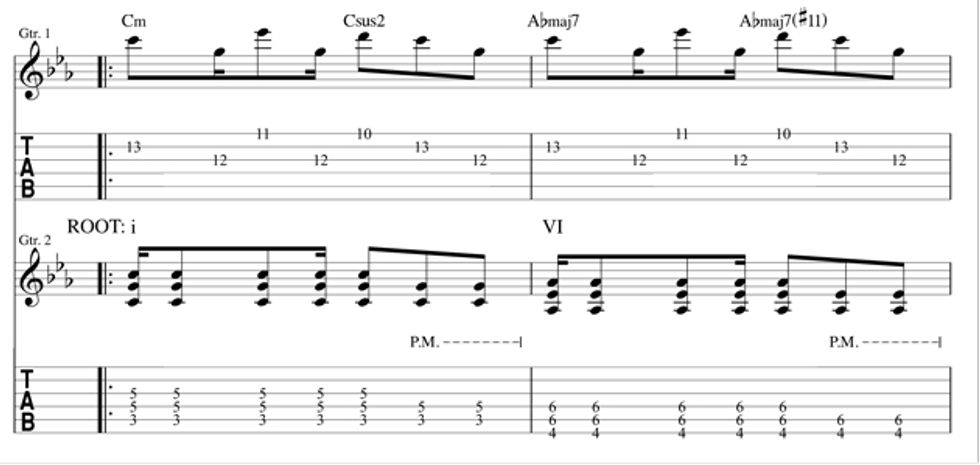

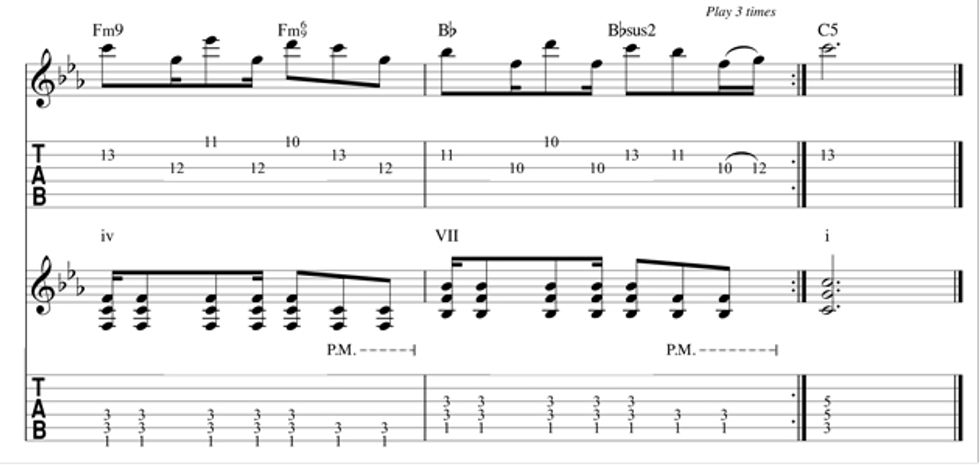

In Fig. 4, we have a progression of Im–VI–IVm–VII in C minor played under a riff that first alternates between Cm and Csus2 chords, and then between Bb and Bbsus2 chords.

Predictably, the first and fourth measures of the rhythm part assume the character of the chords outlined by the lead riff. But some pretty neat stuff transpires on the Ab5 and F5. The notes C and G lift the Ab5 chord to make it into an Abmaj7. In the second half of the bar, the D adds to that a #11. Next, G and Eb, played over F5, suggest an Fm9 chord. When Eb in the riff scooches down a fret to D, we get the sense of an Fm6/9 chord. By the way, m6/9 is one of the coolest chords in all of music.

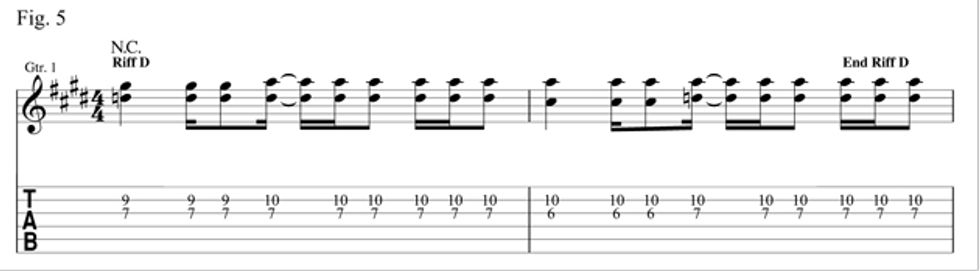

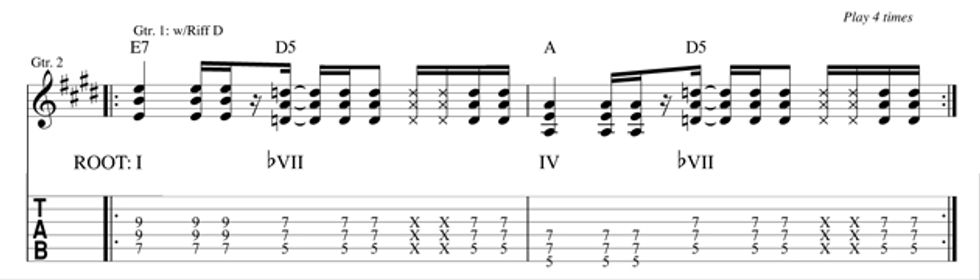

Fig. 5 features a riff playing two notes at a time. Each note, in turn, leads away from the tonal center by a half-step, and then back again as the progression cycles around. The root motion is I-bVII-IV-bVII and ends on I.

The D and G# in the lead riff combine with E5 to form an E7 chord. Then G# moves a half-step up to A so that at bVII, both rhythm and lead parts are playing a D5. Next, D slips down a fret to C# in the lead part, joining forces with an A5 to make an A major triad. Then it’s back to D5 before ending on E7.

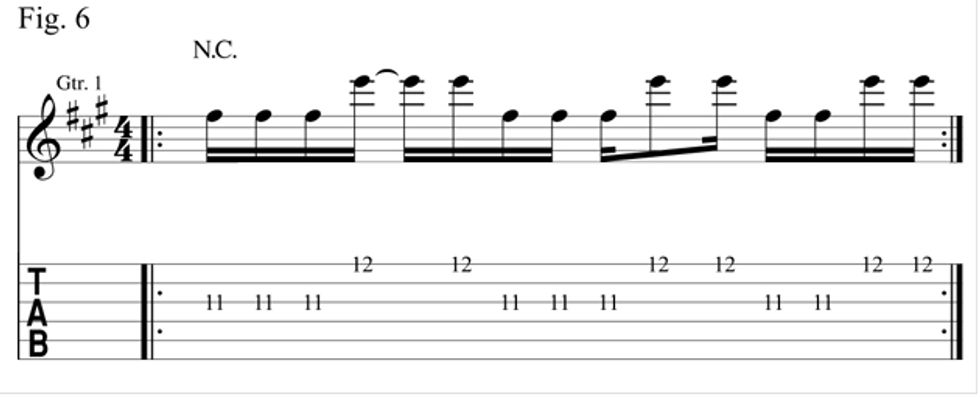

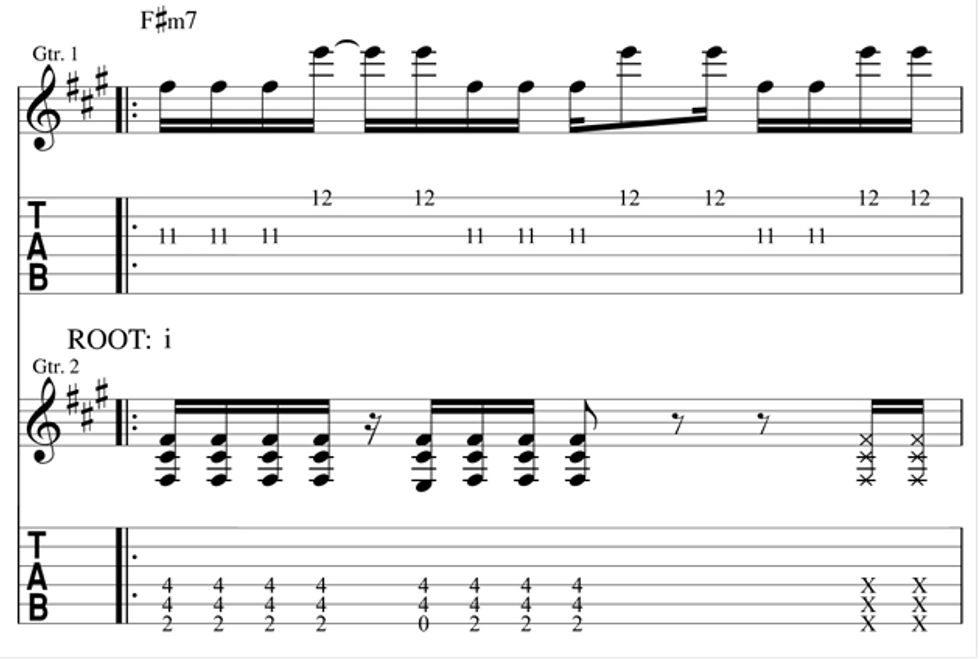

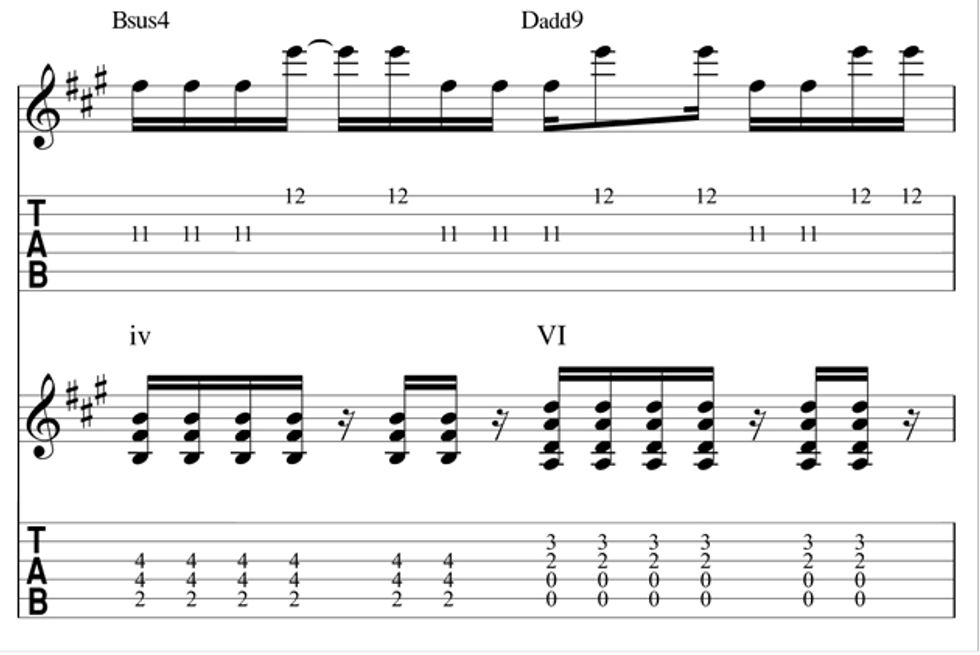

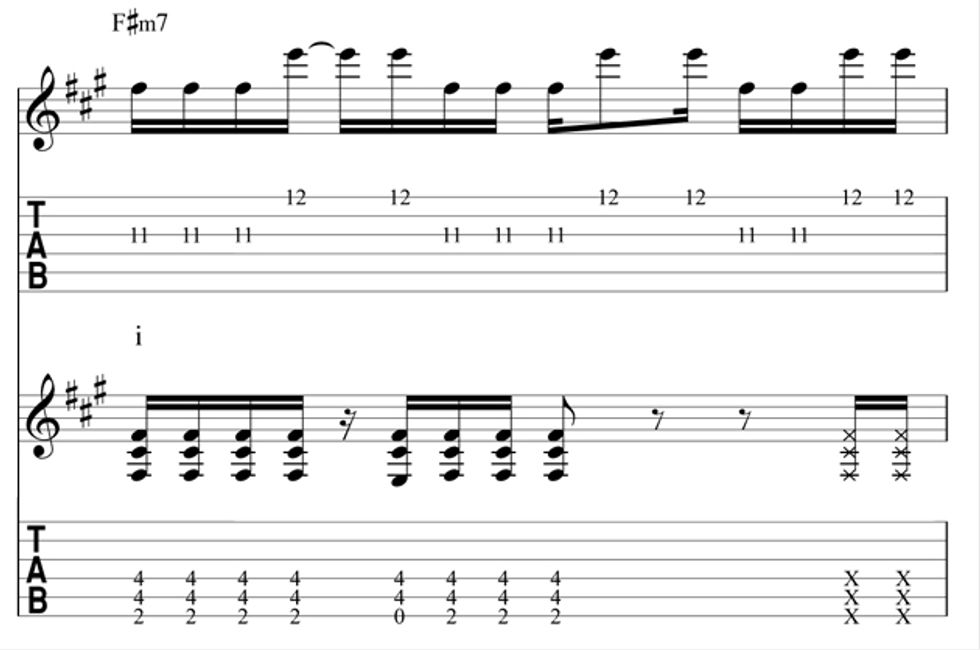

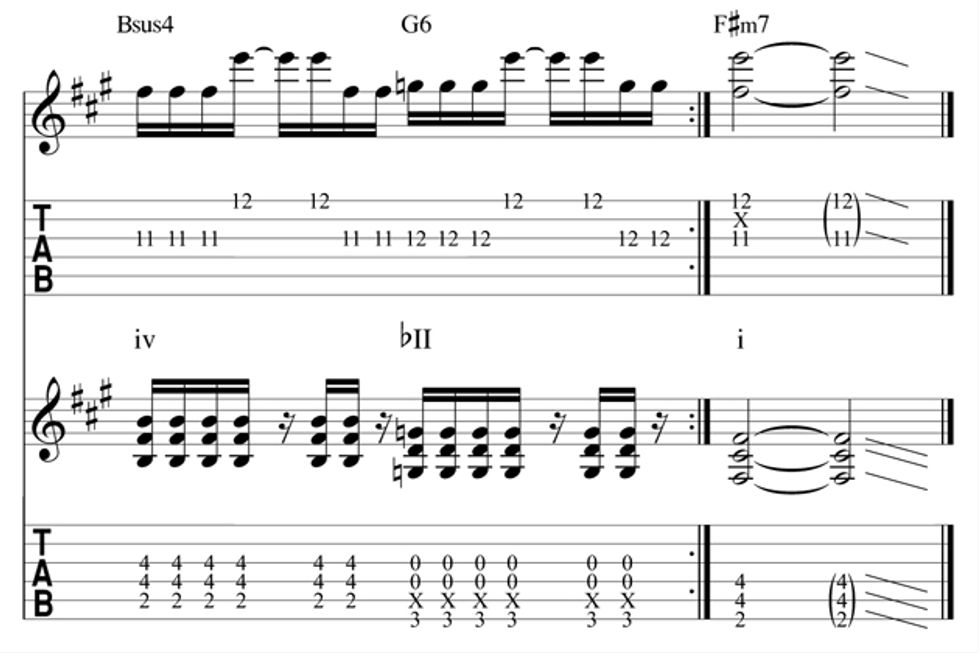

Sometimes a lead part can play a figure built around just two notes. In Fig. 6, the lead guitar plays a riff on the root and 7 of F# minor, forming a minor seventh interval: F# and an E above it. The chord progression is Im–IVm–VI–Im–IVm–bII and ends on Im.

The presence of E over an F#5 chord in the minor key strongly suggests F#m7. Over a B5 chord, the E adds the interval of a perfect fourth, making the IVm chord a Bsus4. When the rhythm switches to D5, the riff provides a 3 (F#) and a 9 (E) to form a Dadd9 chord. The second time through the cycle, a G5 chord is played in place of D5. At this point in the lead riff, F# moves up a fret to G. The E is a major sixth above G and the harmony implied is a G6.

Spicing up simple power-chord progressions is an effective way to get some major mileage out of one of the most vital tools contemporary guitarists possess—the root-fifth construction. The effort it takes to get on a friendly basis with intervals and chord qualities will pay huge dividends and is well worth the time spent. Just remember to keep the riffs simple, but not routine. Complexity dwells just under the surface.