Sun Records chieftain Sam Phillips described the voice of his pre-Elvis discovery Howlin’ Wolf as a sound from “where the soul of man never dies.” For young John Dawson Winter III, the blend of gravel, whiskey, mud, and madness in Wolf’s singing unearthed a well he still draws from 60 years later.

“‘Somebody Walking in My Home’ by Howlin’ Wolf is the first blues song I remember hearing,” Johnny Winter recalls. “I was in my bedroom listening to the transistor radio, and right from the beginning I knew blues was it for me. It had so much feeling. I just loved it. And I could really relate to the black experience. Most people in Texas didn’t like black people because they were too dark, and they didn’t like me because I was too white. I got that even when I was 12 and started playing guitar. By then I knew blues was what I wanted to play, and I still come at it from an emotional perspective—not technical.”

Nonetheless, it was the conflagrant intensity of Winter’s two-fingered picking, the bared-fang snarl of his tone, and the mix of sand and kerosene in his own voice that skyrocketed him from the Texas psychedelic club scene into the international music spotlight less than a year after he recorded his debut, The Progressive Blues Experiment, on the stage of Austin’s Vulcan Gas Company in 1968. By the end of 1969 he’d released his major-label debut, Johnny Winter, and the follow-up, Second Winter, and played Woodstock, laying out blueprints for the future of American blues-rock and even Southern rock.

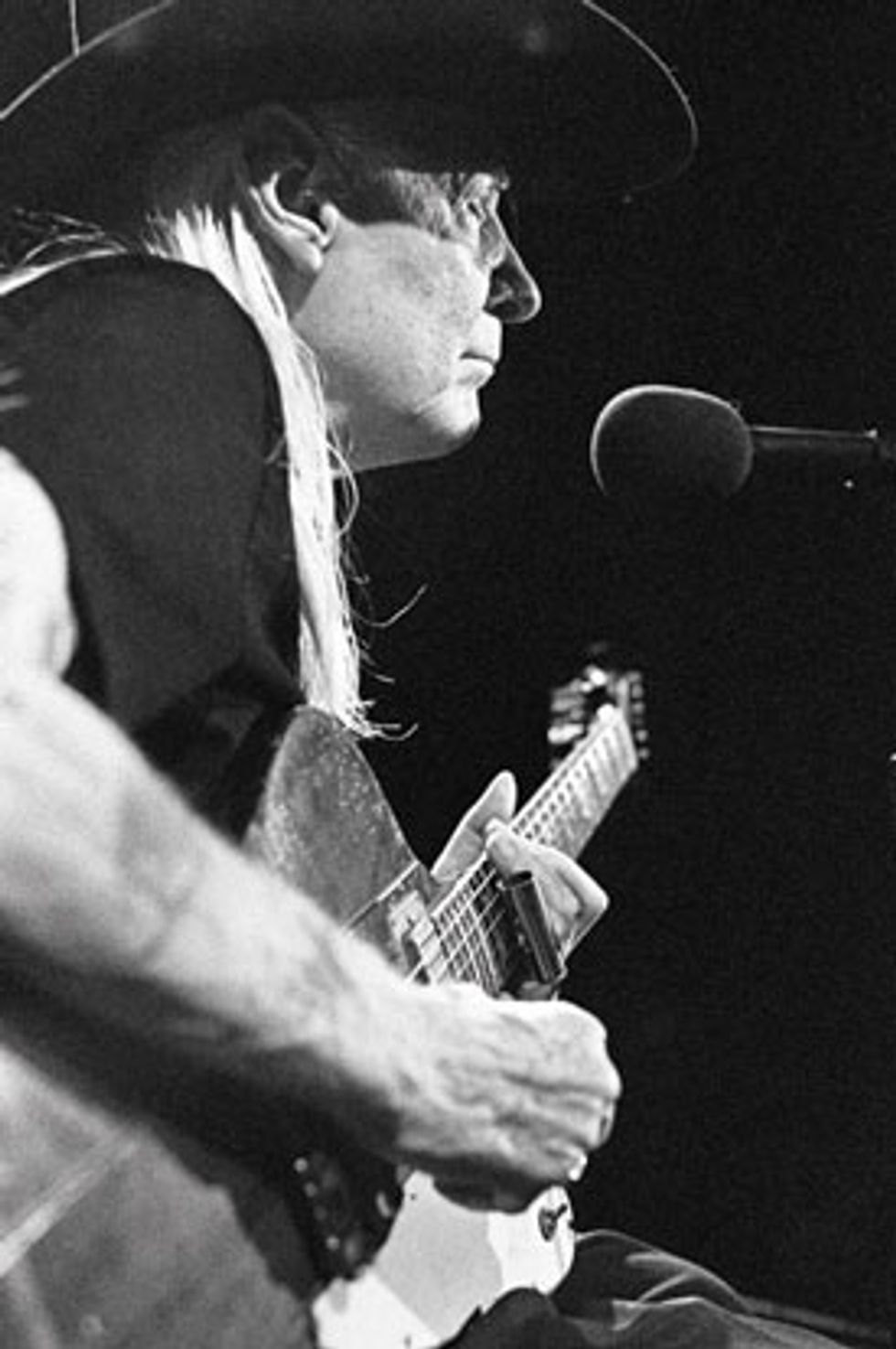

Although Winter is currently enjoying a surprising late-career renaissance thanks to his recharged stage presence, a documentary film, and a spate of releases, it’s the images of him from 1969 to 1974 that are burned into the retina of rock history: rail thin and wrapped like a spider around the 1963 Gibson Firebird that still accompanies him onstage, wraith-like thanks to his albinism and long hair, literally attacking the strings.

“I use a Dunlop slide that’s snug on my finger, so I can fret with the slide and move faster and more exactly,” says Winter. He favors open D and G tunings, and sometimes A. “It all depends on where

my voice is,” he says.

Winter’s star continued to rise during those years, after Columbia Records persuaded him to form a new band with co-guitarist Rick Derringer that cut the influential Johnny Winter And and Still Alive and Well sets. Those albums along with the Allman Brothers first titles cast the die for two-guitar blues-rock ensemble playing. Many think the four LPs Winter made with Derringer define his golden era, but Winter still complains that Derringer played too much and too loud. “All I need to play well is a good strong snare beat and other musicians who don’t get in the way,” he says.

Winter prefers the string of discs he made in the late 1970s with blues groundbreaker Muddy Waters and Waters’ band, his own Nothin’ But the Blues, and the Grammy-winning trio Hard Again, I’m Ready, and King Bee that he produced for Waters.

But something was amiss in those glory days. By the early ’70s Winter had become a heroin addict. And while he was able to kick that drug, he got hooked on methadone, which, along with alcohol abuse, put Winter on a long spiral that brought him to the bottom roughly a decade ago. Sure, there were some high-notch concerts and recordings along the way, like 1984’s Guitar Slinger and 1992’s Hey, Where’s Your Brother?—a nod to his pop-hit instrumentalist sibling Edgar Winter. But by the time Johnny met his current manager, co-guitarist, producer and, in practical terms, savior Paul Nelson in 2004, Winter seemed like a shell of himself, appearing exhausted and occasionally out of tune onstage, revived only by the spirit of the blues that seemingly inhabits his bloodstream.

“I had a good time and enjoyed drugs and drinking,” he says by phone from his Connecticut home, “but I overdid it. It was great in my 20s. The older I got the worse it was for me. It took me a long time to figure out that takin’ dope is not good for you.” He chuckles. “Now, I feel great. Physical therapy helps, but so does not taking drugs or drinking. A lot of people I know are dead. I could have died a bunch of times. Maybe I died years ago, but God was on my side.”

Perhaps that accounts for Winter’s ongoing resurrection. In 2011 he broke a seven-year recording hiatus with the album Roots, revisiting some of his favorite blues classics with the help of such guests as Warren Haynes, Derek Trucks, Susan Tedeschi, Vince Gill, Edgar Winter, and others. The disc was heralded as a partial return to form.

This February the four-disc retrospective True To the Blues: The Johnny Winter Story was released. His upcoming Step Back,due in September, amps up his previous studio recording’s strategy with an edgier, more rocking approach and appearances by Eric Clapton, Leslie West, and Billy Gibbons, to name a few. And the documentary Johnny Winter: Down and Dirty debuted at the South By Southwest Film Festival in March. The movie frankly chronicles both Winter’s storied history and the past two years of his life, which meant that director Greg Olliver was a regular aboard the Winnebago the guitarist uses to travel to about 120 dates annually.

Right-Hand Man

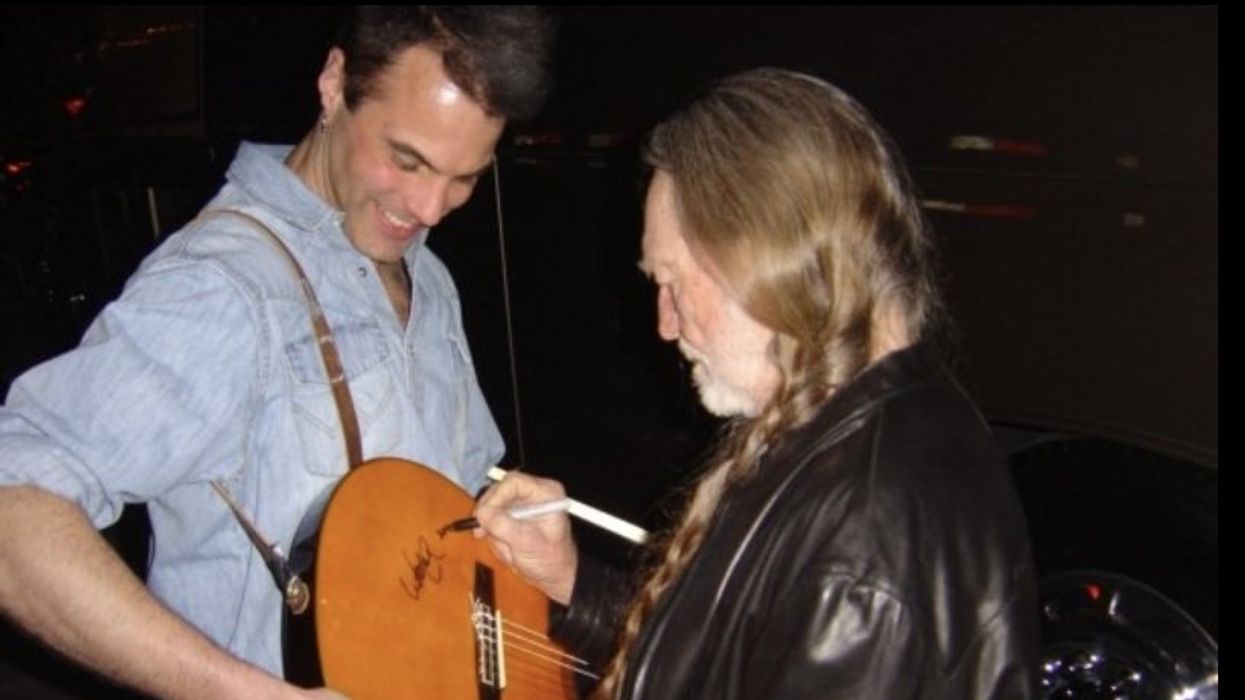

Photo by Michael Weintrob

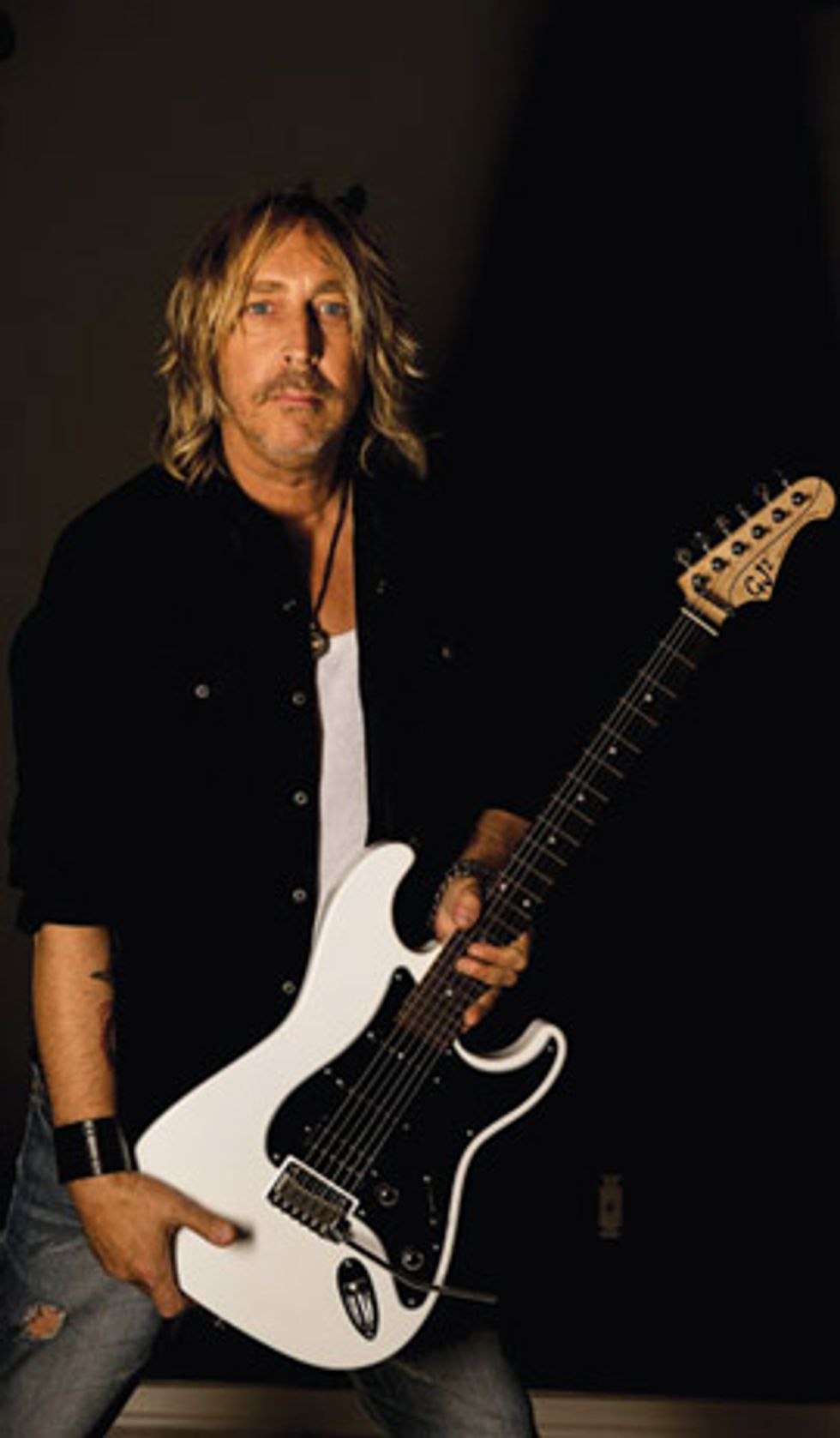

Paul Nelson is Johnny Winter’s supporting guitarist, producer, and manager, but his most important role is friend. If Nelson hadn’t made what was essentially a one-man intervention in Winter’s life nearly a decade ago, the guitar hero who ascended from Texas dive bars to the stage at Woodstock in a single year after recording his debut album would likely be pushing up posies instead of bending strings.

They met while Winter was cutting 2004’s I’m a Bluesman at Carriage House Studios in Stamford, Connecticut. “Johnny heard me playing some blues next door during a session I was doing for the World Wrestling Federation, and invited me to meet him,” Nelson recounts. He was recruited as a songwriter and second guitarist on the project, and when it was over Winter invited Nelson on the road.

“What he liked about me is that I was one of the few guitarists he played with who didn’t step all over his playing,” Nelson recounts. “Johnny said, ‘With everybody else, it was always a guitar war.’ I only do what needs to be done. If Johnny plays single notes, I play chords. If he plays low, I play high. It’s simple. I stay the hell out of his way and make everything sound bigger.

“Johnny took me under his wing and immediately started teaching me the blues riffs he’d learned from Muddy Waters,” Nelson says. “As I became more comfortable I started telling him the emperor had no clothes. He was singing and playing like crap, and practically falling asleep onstage. This had gone on for years with nobody trying to help him. So he asked me if I’d manage him. I said, ‘Yes, if you give up the drugs and drinking, start doing something about your health, and get back to being Johnny Winter.’ Believe me, there was a lot of screaming and fighting along the way, but he did it. There were huge changes the moment the drugs and stuff were gone—but try telling a rock star from the ’60s that!

“Some days,” ponders Nelson, “I wonder, am I his producer, his band mate, his manager, his pal? Or maybe I’m really the luckiest fan in the world.”

Nelson was well into a successful career as a session player, producer, solo artist, and hard-rock guru with credits ranging from Leslie West to Los Lobos to Steve Morse when he signed on as Winter’s manager. As a youth, he was already enraptured by the playing of Winter, Billy Gibbons, Jimi Hendrix, Albert King, Jeff Beck, Wes Montgomery, and Larry Carlton when he attended Boston’s Berklee College of Music, then went on to study with Mike Stern, Steve Kahn, and Steve Vai. So Nelson had plenty of 6-string smarts and studio skills to apply to Winter’s 2011 album Roots, as well as the new album Step Back.

Both sets feature blues chestnuts and all-star casts, with the lineup on Step Back including Eric Clapton, Ben Harper, Brian Setzer, Leslie West, Billy Gibbons, Joe Perry, Dr. John, and harmonica demon Jason Ricci. Nelson also duets with Winter on “Killing Floor,” a song originally recorded by blues giant Howlin’ Wolf for Chess Records in 1964.

“When Johnny was ready to make this album, he picked the songs in 15 minutes,” says Nelson. “These are songs he’s loved all his life.” Nelson had the rhythm section learn the original version of each of the blues classics, and then had them learn another version recorded a few decades later before they worked with Winter on the album’s arrangements. “That way they’ve got perspective going into the session with Johnny,” he explains. When the basic tracks were done, they were sent to Winter’s handpicked guests, who added their parts.

To make the guest guitarists’ parts gel with Winter’s playing, Nelson duplicated the mic setups used by each player. “Clapton, for example, used a small amp and overhead mikes,” notes Nelson, “while Leslie West put a microphone right in front of his amp’s speaker. When I use the same approach to record Johnny, it sounds like they cut their guitar parts together in the same room.” Winter owes two more albums to Megaforce Records per his contract, and Nelson has also signed a deal to record solo for Megaforce.

Nelson says that winning a Grammy and being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame top Winter’s bucket list. “He’s told me, ‘I’m at a point in my life where I love receiving awards. Give me awards.’”

Johnny Winter is known for his beloved Gibson Firebird, but he also plays a Lazer from Erlewine Guitars. He likes the Lazer because it stays in tune and sounds trebly like a Fender, but plays like a Gibson. He uses the Firebird primarily for slide and keeps it in open-D or G tuning.

All of this, and the fact that Winter is concentrating on recording and playing so many of the songs that first drew him into blues, makes him as happy as a 70-year-old kid in a candy store. “I never thought I’d reach this age, but I’m damn glad I did,” the high-speed string-slinger says. “I’d rather be old than dead. And I love playing the blues now as much as when I was 12. Maybe more. I could make albums of songs by Gatemouth Brown and Jimmy Reed and Muddy until I drop.”

Winter still has a bucket list: “I’d like to write some more original numbers,” he says, “but I haven’t had any song ideas since 2004. I’d also like to win a Grammy for one of my own records. And I’d like to go to Egypt—not even to play music, but just to see the pyramids and stuff. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame would be nice, too, but I’d rather have the Grammy. And I want to get it for playing good blues.”

Johnny Winter's Gear

Guitars

1963 Gibson Firebird

Dean “Z” series Johnny Winter signature model

Amps

Music Man 4x10 combo

Effects

Boss CE-2 Chorus

Strings and Picks

Strings, Picks and Slides

DR Pure Blues .010–.046 gauge

Fender medium thumb picks

Dunlop Johnny Winter Texas Slider

Another complaint Winter airs is that he considers his early records more rock than blues: “I really wanted to play blues, but in the early ’60s the white people didn’t want to hear us play that, especially in Texas, so when we started out it was more rock and R&B. It was frustrating, because I was in love with blues.”

Winter attended his first blues show at age 14: a Ray Charles concert at the Municipal Auditorium in his native Beaumont, Texas. Three years later he had a pivotal experience at that city’s Raven club. “I went to see B.B. King play for about 1,500 to 2,000 people—all black. It was great music, nobody bothered us, and after I met him, B.B. let me play,” he recounts. “It felt great to get a standing ovation from an all-black audience. I felt like I had to be playing the music right. B.B. didn’t even know if I could play. If I was in his place I don’t think I would have let me. He’s one of the nicest people in the world.”

By that time Winter’s oddball, lightning-strike thumb-and-forefinger picking style was already well developed. “It seemed to come naturally to me,” he observes. “A lot of the older black guys played with thumbpicks, but I started using one because I liked Chet Atkins and Merle Travis. Chet got his style from Merle. They probably influenced my speed, too. I’ve always played hard and fast. After all these years, I still play the way I did when I was 15. And my gear hasn’t changed much since 1970 when I got my Firebird.”

Winter acquired that iconic instrument at a festival, where a guitar dealer from St. Louis brought it and a clutch of other 6-strings to sell to the musicians on the bill. “I was already playing Les Pauls and Stratocasters,” Winter recounts. “The first really good guitar I’d gotten was a Black Beauty ‘fretless wonder,’ but when I saw that Firebird I thought, ‘I’ve got to try that!’ The neck’s been broken four or five times over the years. I keep getting it fixed. But everything is stock. I always thought it was fine the way it was, so I never messed with it.”

Winter still plays the Music Man 4x10 combo amps that Muddy Waters turned him onto during their ’70s collaborations, favoring those over the Fender Super Reverbs he’d used until then due to their higher wattage. His settings: volume and treble on 10, everything else at zero. And Winter’s one effect remains an old Boss CE-2 chorus pedal, “just to make things a little fuller.”

Waters was also a major influence on Winter’s slide playing, which is as much a signature as his ripping single-note solos. “Muddy, Elmore James, Robert Johnson, Son House—they got me interested in slide,” Winter explains. “I use a Dunlop slide that’s snug on my finger, so I can fret with the slide and move faster and more exactly.” He favors open D and G tunings, and sometimes A. “It all depends on where my voice is,” he says.

YouTube It

Because the upper range of his voice dissipated after decades of howling “rock ’n’ roll” into microphones to kick off his sets and growling like a frisky badger for the rest, Winter started dropping his standard tuning down a whole step to a D about 20 years ago. “Otherwise, I’m pretty much doing the same kind of thing I’ve done all my life: playing the same kind of music I love—the blues—the same way I always have.”

As Winter reflects on his career, it’s obvious that Muddy Waters remains his brightest musical beacon. “I played with a lot of people over the years,” he says. “Jimi Hendrix. Eric Clapton. But without a doubt, Muddy was the most important for me. I met him for the first time when we opened for him at the Vulcan Gas Company, where all of the psychedelic bands, like the 13th Floor Elevators, played. So the psychedelic sound got into my playing as well. But Muddy was it. His name and ‘blues’ were inseparable to me. And I feel the same way that Muddy felt about the music. When people come to see me I want them to know they’re going to hear good blues and that I play what makes me feel good, and that I’m interested in sharing that good feeling with them.”On Candid Camera

Sure, director Greg Olliver’s rock-doc Johnny Winter: Down and Dirty provides a through-the-Winnebago-windshield view of the life of the Texas guitar legend as he travels the U.S. and Japan, and reminisces about his adventures with Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and his idol, Muddy Waters. But it also busts myths about his health and history, thanks to Winter’s relentless candor.

Early in the movie, which premiered at this year’s South By Southwest Film Festival, we see Winter receiving a visit from a physical therapist and struggling through exercises designed to strengthen and lengthen his back muscles, atrophied from years of bad posture, chemical abuse, and general neglect.

“Not everybody would allow a filmmaker to show them being vulnerable like that,” says Olliver, who also directed the critically heralded 2010 documentary Lemmy, about Mötorhead’s Lemmy Kilmister. “Johnny isn’t a rock star. He’s a real person and one of the most frank and open people I’ve ever interviewed, which made the two years I spent working on Down and Dirty really fun. Not once did he ever hold back.”

But viewers also see Winter enjoying life—horsing with his friends and his accomplice, manager/guitarist Paul Nelson, and taking pleasure in simple, but deep, pleasures like spinning a Robert Johnson record on a phonograph. There’s also plenty of live performance footage and cameos from Billy Gibbons, Joe Perry, Derek Trucks, and others commenting on the power and durability of Winter’s influence and legacy.

Olliver says his decision to train his lens on Winter came organically. Like the 6-string legend, Olliver was born and raised in Texas and grew up on the sound of blues from its originators and well as Lone Star heroes the Fabulous Thunderbirds and ZZ Top. When Olliver approached Winter and Nelson, they readily accepted.

Once Olliver got on the Winnebago, he discovered another bond with Winter: a love of horror and science-fiction films. “Johnny loves to stay up late at night on the bus watching B movies,” Olliver recounts. His taste varies widely. Two favorites are the 1956 classic Forbidden Planet and the hideously bad 1972 Ray Milland vehicle Frogs, which, to borrow Olliver’s description, “is about a bunch of frogs hopping around a plantation killing people.”

Olliver’s own project between Lemmy and Down and Dirty was Devoured, a genuinely creepy horror film that’s just been released in the U.K. “Johnny said that he loved it,” Olliver notes.

The glue between his two documentaries and Devoured is Olliver’s gift for storytelling. But there are some stories that didn’t make the final cut of Down and Dirty. “When we were in Hong Kong, Johnny said, ‘Hey, we should find some opium, and then we’re gonna put it up our butts.’ I said, ‘Johnny, if there are two things I’m not going to do on this trip, it’s find opium and put it up my butt.’

“When I told [veteran Winter and Double Trouble bassist] Tommy Shannon that story, he said, ‘You know, there was a time and a place when that sort of thing was perfectly acceptable.’”

For updates on the film’s availability, check johnnywinterdownanddirty.com.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.