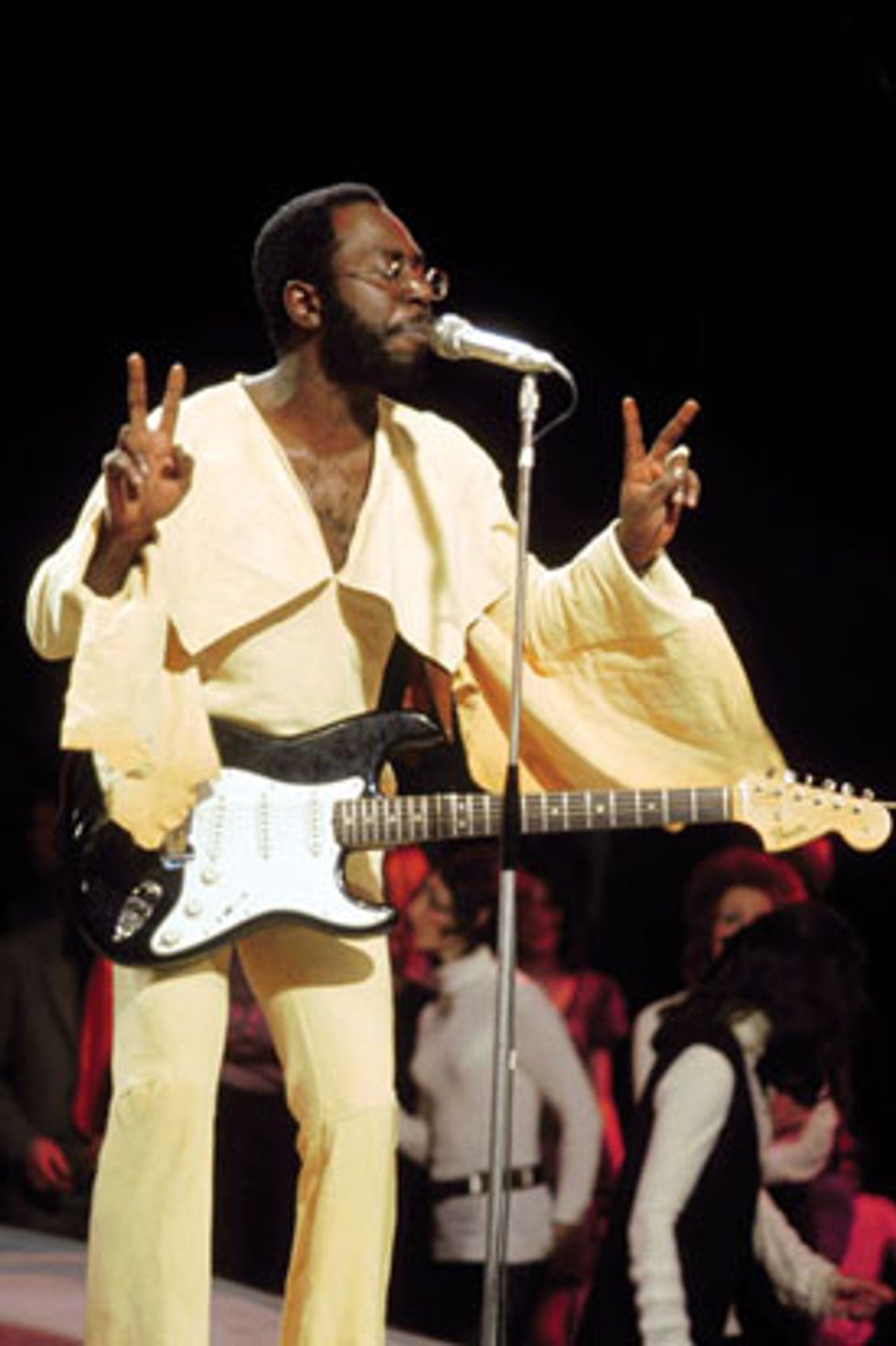

Curtis performing in 1973. Photo by Neil Zlozower.

Anyone with a passion for soul music should know the name Curtis Mayfield. His classic songs about the racial and political upheaval of the 1960s were powerfully poignant back then and, unfortunately, still topical even today. His distinctive falsetto singing over strummed, wah-treated guitar passages fleshed out by a powerful rhythm section and orchestral sweetening produced a dozen hits from the ’50s to the ’70s. A multi-instrumentalist who played guitar, bass, piano, saxophone, and drums, Mayfield was awarded the Grammy Legend Award in 1994 and the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award the following year, and was a double inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame—in 1991 as a member of the Impressions, and again in 1999 as a solo artist.

But for guitarists, it is the Chicago-bred Mayfield’s distinctive 6-string style that stands out. Band of Gypsys bassist Billy Cox feels Hendrix drew on Mayfield for recordings as early as “Little Wing” or “Castles Made of Sand,” and as late as “Drifting,” while Funkadelic’s George Clinton has been quoted as saying, “In the ’60s, every guitar player wanted to play like Curtis.”

The Original Black Keys

Curtis Lee Mayfield was born in Chicago on June 3, 1942. Though his mother had her hands full raising him and four other children on her own, she still found time to sing and play piano—and she encouraged a very young Curtis to sing as well. By age 3, he was performing “Pistol Packin’ Mamma” in public, and by 7 he was singing at his grandmother’s church with the Northern Jubilee Singers. As part of that group, Curtis met Jerry Butler, and together the two future members of the Impressions grew up singing in the churches of pre-war Chicago.

In his teens, Mayfield began to teach himself guitar. With no one to tell him differently, he tuned the strings to the black notes of his mother’s piano: F#–A#–C#–F#–A#–F#. This led his songwriting down unique paths and informed licks that would influence generations of guitarists—not just in soul music, but also in rock, blues, and even country.

Mayfield and Butler eventually split from the Northern Jubilee Singers to form the short-lived Modern Jubilaires. Subsequently the two went their separate ways for a while, but later Mayfield was convinced to quit his own group—and school—to play guitar for Butler’s band. He was 15 years old when he set out to become a professional musician.

The Roosters picked up a manager who convinced them people would stop making barnyard sounds at their gigs if they changed their name. Eager to impress audiences, they rechristened themselves the Impressions. The same manager arranged an audition with Chess Records, but when the band arrived they found the doors locked. Vee-Jay Records (the first label to sign the Beatles to an American deal) was right across the street, so they auditioned there instead. Signed to Vee-Jay subsidiary Falcon (later Abner) records, Mayfield and the Impressions quickly recorded the Butler-penned “For Your Precious Love,” which became a big hit in the summer of 1958. Mayfield’s guitar arpeggios start off the tune, setting the type of groove normally laid down by a piano on a ballad of this sort.

The single was released under the name “Jerry Butler and the Impressions,” which created discord among band members. Before it got out of hand, they were on tour, breaking box-office records at New York’s Apollo Theater. It was during their Apollo run that Mayfield realized his F# tuning was unusual and could occasionally cause problems when trying to play with the house band.

When Butler left to pursue a solo career, Mayfield took over as the Impressions’ main singer. Failing record sales, arguments over Mayfield’s publishing rights, and lack of label confidence in him as a lead singer led Abner Records to drop the group, and the Impressions temporarily disbanded. Butler then called and asked Mayfield to be his road guitarist in place of Phil Upchurch, who left to tour behind his own hit instrumental, “You Can’t Sit Down” (predating the Dovell’s vocal version). So the 18-year-old Mayfield spent 1960 backing Butler, an experience that improved both his guitar playing and singing. He continued to write songs as well, 14 of which were recorded by Butler during the height of his career—including the oft-covered “He Will Break Your Heart,” which went to the No. 1 slot on the R&B charts and the No. 7 spot on the pop charts.

That same year, the teenage songwriter and his manager Eddie Thomas formed their own publishing company, Curtom. This was revolutionary among the commonly exploited R&B performers and writers of the era, who were more often hoodwinked or coerced into sharing publishing with everyone from label owners to DJs.

Voice of a Movement

In 1961, the Impressions reformed and landed a contract with ABC-Paramount Records in New York City, based on a demo recording of Mayfield’s “Gypsy Woman.” The song soon became an international hit. The Impressions’ career faltered after that, but by then Mayfield’s songwriting, producing, and guitar sound were in high demand from R&B artists who hoped his touch would help them achieve similar successes.

Back in Chicago, Mayfield teamed up with arranger Johnny Pate to produce his next round of hits. Working with Okeh Records label head Carl Davis, they produced Major Lance’s “Monkey Time”—a Top 10 pop single that was emblematic of the production team’s sound: Mayfield’s guitar underpinning heavy bass, brass, and strings, all of which was shored up by the Impressions’ backing vocals. In 1963, the Impressions had another hit of their own: Mayfield’s affirmative “It’s All Right.” Their next single, “Talking About My Baby,” joined the Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “I Saw Her Standing There” on the 1964 top 20 charts. And despite the pervasive power of the British Invasion, the Impressions scored yet another hit that year with the Mayfield-penned “I’m So Proud” (later covered by Jeff Beck in Beck, Bogert & Appice).

The Impressions’ 1964 hit “Keep on Pushing” marked the beginning of Mayfield’s topical lyric writing. It dealt with the rising civil rights movement being spearheaded by Martin Luther King Jr. Despite—or perhaps because of—its gospel roots and movement-oriented lyrics, “Keep on Pushing” struck a popular chord, rising to No. 10 on the charts. Other Mayfield-penned Impressions’ songs on the charts that year included the classic singles “You Must Believe Me” and “Amen.” The album Keep on Pushing, which boasted all of the band’s aforementioned1964 hits, brought the Impressions to their highest point of popularity to date.

YouTube It

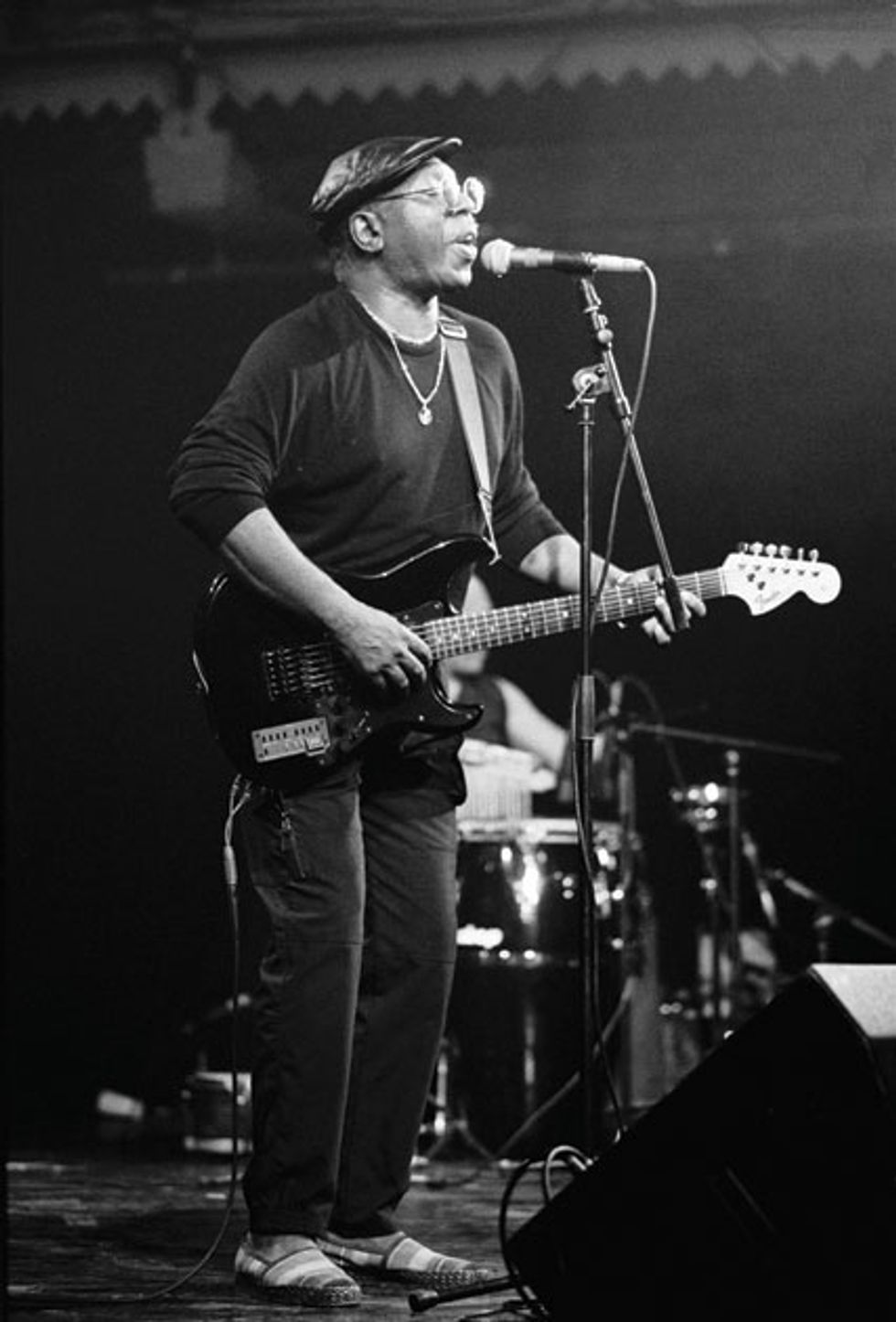

In this 1990 footage from the German television program Ohne Filter, Curtis Mayfield is in top form—both in terms of vocal delivery and 6-string finesse.

But 1965’s People Get Ready delivered even more hits that would go on to become R&B standards. On the gospel-inflected title single, pizzicato strings on the left side occasionally double Mayfield’s rhythm chucks on the right. About halfway through, everything stops for his double-stop melody interlude, which modulates the song up a half-step. The lyrics about inclusiveness and upward mobility became an anthem for the civil rights movement.

By the mid ’60s, the Impressions had become a worldwide sensation, but their music had a special impact on Jamaica, where their socially conscious lyrics and Mayfield’s guitar playing influenced Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff, and others. In addition, Mayfield continued to write and produce hit records for artists such as Major Lance, Gene Chandler, and Jerry Butler. By age 23, Mayfield had defined a Chicago soul sound that rivaled Motown.

Unfortunately, the next Impressions album failed to capitalize on their place as the voice of a movement. It retreated to a collection of slick standards and, for the first time ever, the group failed to chart.

Setting out on His Own

The Impressions may have been lagging post-People Get Ready, but Mayfield was going full steam ahead. He started his own independent label, Windy C, in the spring of 1966. He also ran Mayfield Records to showcase a girl group called the Fascinations. A historically interesting act on Mayfield Records was the Mayfield Singers, a group of Howard University students including a then-unknown Donny Hathaway. Their version of the label owner’s “I’ve Been Trying” is notable for its up-front mix of Curtis Mayfield’s classic playing.

The doors at Mayfield Records and Windy C were closed with the advent of the singer’s Curtom label, but these two independent labels gave Mayfield a chance to build his executive chops while waiting for the Impressions’ contract with ABC to be finished so he could sign them to Curtom Records. The Impressions left ABC on a positive note by returning to their winning brand of soulful message music on the aptly titled “We’re a Winner”—a track that found Mayfield’s joyous sliding sixths featured prominently in the mix.

In 1968, Curtom was officially launched at a Buddah Records convention by Buddah vice president and general manager Neil Bogart (who would later go on to work with Kiss, Donna Summer, and the Village People on his own Casablanca label). Mayfield produced the Impressions on his new label, in addition to adding young Donny Hathaway as an artist, cowriter, and arranger. More soul history was created at Curtom when Moses Dillard and Tex Town Display released two singles featuring the recording debut of Peabo Bryson.

In ’69, the Impressions released “Choice of Colors,” a Mayfield tune that was to continue his string of classics confronting the racial issues of the day, but it was their wah-wah-powered recording of “Mighty, Mighty (Spade and Whitey)” that presaged the more pointed political attitude Mayfield would take in his solo career.

In 1970, Mayfield’s first solo record, Curtis, continued his social commentary with the psychedelic soul of “(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Below We’re All Going to Go” and “Move on Up.” These songs defined what was to become Mayfield’s signature sound: open-strummed funk rhythms, wah-pedal action, and driving congas. It’s unclear whether Mayfield played guitar on the record or left it to the guitarist he replaced with Jerry Butler, Phil Upchurch, but the style of playing is pure Curtis.

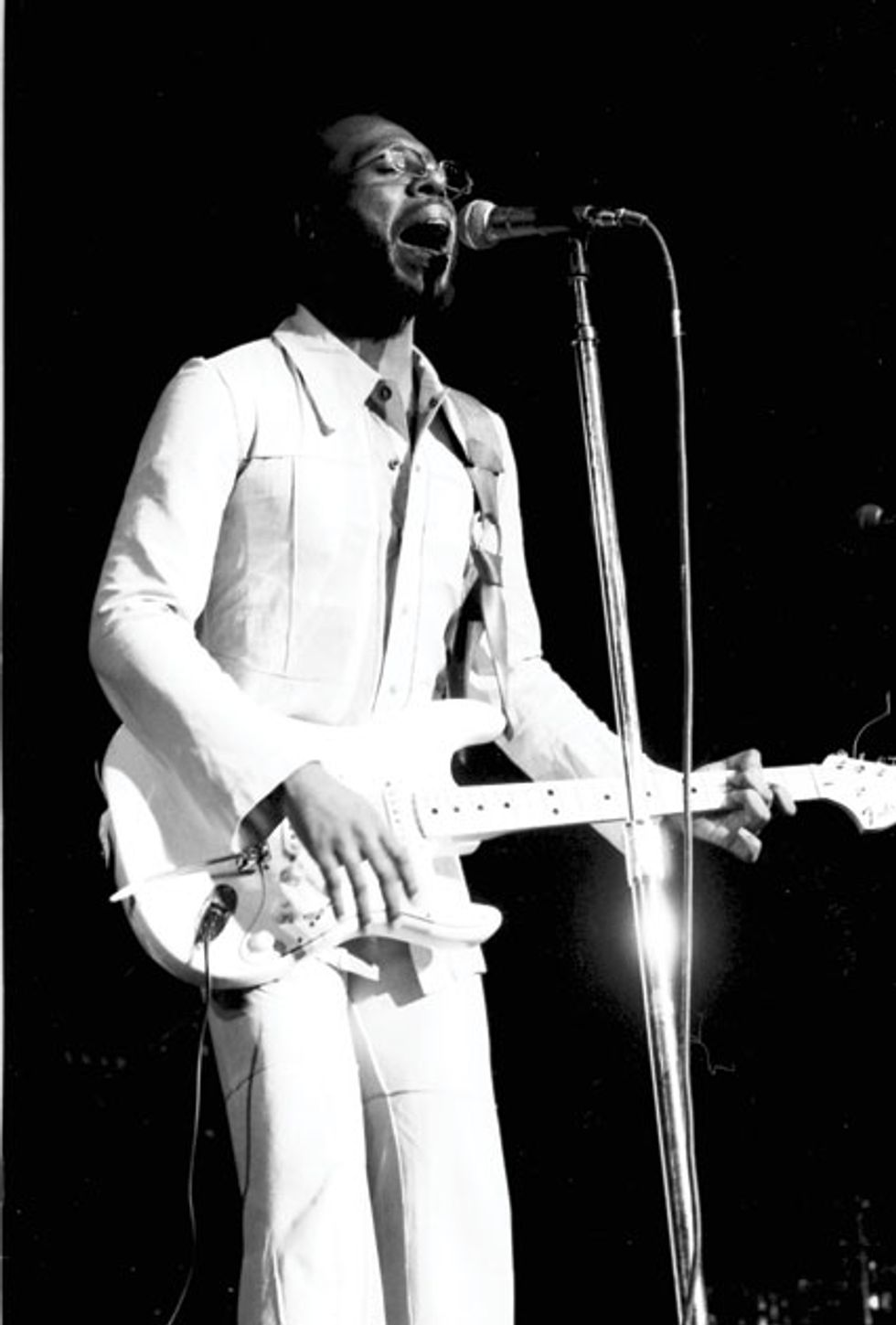

There is no doubt about who is playing on his next album, Curtis/Live! Released less than a year later, this performance at the Bitter End in Greenwich Village stripped away all the strings, woodwinds, and backing vocals, leaving a quintet consisting of Mayfield (vocals, guitar), Craig McMullen (guitar), Tyrone McCullen (drums), “Master” Henry Gibson (percussion), and Joseph “Lucky” Scott (bass). Mayfield’s and McMullen’s playing can be clearly discerned as their guitars intertwine in a soul version of Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir. McMullen’s Gibson takes over rhythm when Mayfield stops playing his Fender to sing a particular passage or talk to the audience.

“Get Down,” which opens Mayfield’s other 1971 record, Roots, maintains the energy of the live record and—with distorted bass, rhythmic vocal breathing, and fuzzed-out guitar—sounds surprisingly contemporary. “Keep on Keeping On” and “We Got to Have Peace” continued Mayfield’s inspirational messaging, though they also sounded a bit like retreads, a fact reflected by sales numbers. The songwriter would regain some creative energy with his next solo project, Back to the World, which dealt with returning Vietnam vets and the general deterioration of the modern world. But first came the phenomenon that was Super Fly.

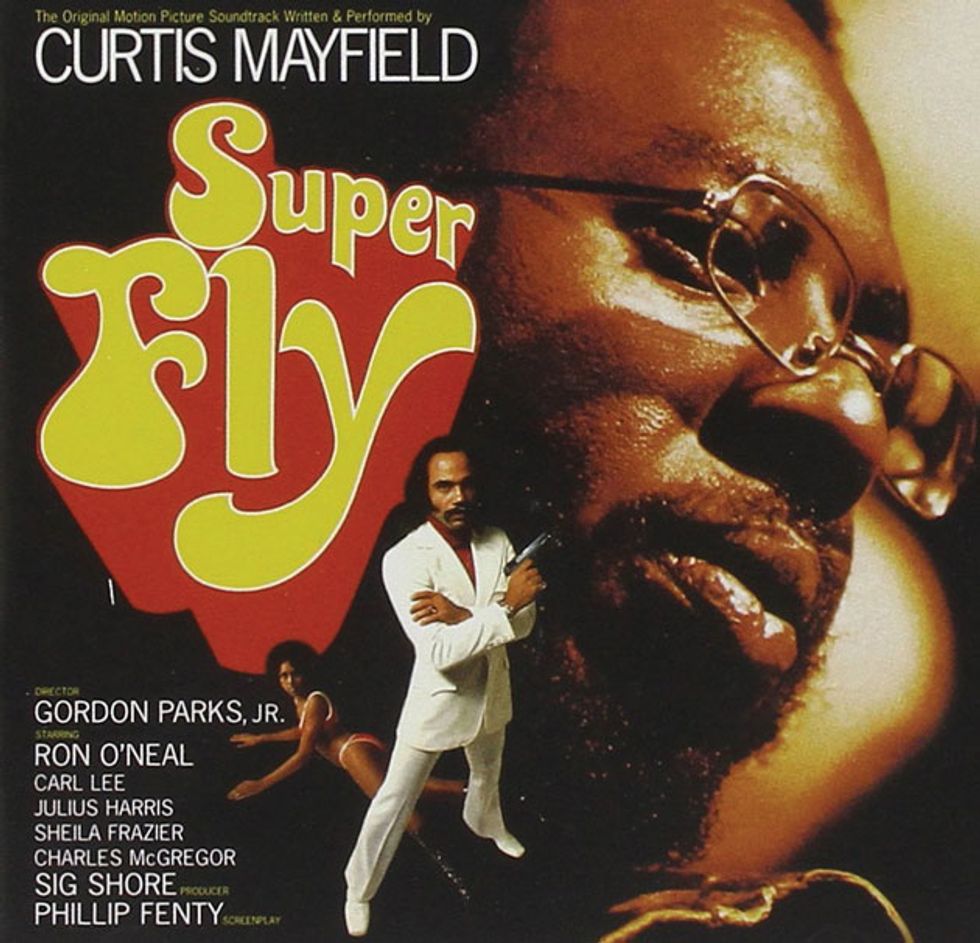

The Super Fly soundtrack is Mayfield's most-popular release to date as it has sold millions and

actually out-grossed the film.

The Super Fly Effect

The ’70s saw the rise of “blaxploitation” movies featuring African-American anti-heroes battling pimps, drug dealers, hookers, and corrupt cops. The first notable movie of this kind was Shaft (1971), which featured a score by Isaac Hayes and an eponymous title song that became a huge hit. Mayfield subsequently scored Gordon Parks Jr.’s 1972 film Super Fly, about a drug dealer trying to get out of the game. Though it is considered classic Curtis now, at the time Mayfield refused to issue “Pusherman” as a single out of fear that its message might be interpreted as pro-drugs. In a July 2012 interview with The New York Times, Mayfield’s widow, Altheida, said that upon first reading the script, “Curtis felt Super Fly was a commercial to sell cocaine, and he wanted to turn that around … his main purpose there, [was] to say, ‘This is nothing pretty.’”

The more cautionary soundtrack offering “Freddie’s Dead” became a big hit at the time. With the added success of the title tune—and eventually “Pusherman,” as well—Super Fly became Mayfield’s biggest-selling album ever.

The success of Super Fly pushed back the release date of Back to the World, but Mayfield continued to release solo projects alongside his movie work, sometimes recycling songs written for a soundtrack on his own record or vice versa. His soundtrack for the movie Claudine featured Gladys Knight & the Pips on vocals, while that same year he released his own Sweet Exorcist—the latter of which produced the R&B hit “Kung Fu.” Predating Carl Douglas’ “Kung Fu Fighting,” it drew on the popularity of the television show of the same name, as well as the recently deceased Bruce Lee’s popular movie Enter the Dragon. Listening to “Kung Fu” today, it’s easy to hear how Mayfield’s vocal stylings might have influenced someone like Prince as much as his guitar sound.

Perhaps due to all this success and demand, the early ’70s found Mayfield spreading himself thinner than ever: Between movie soundtracks, forming another label (Gemigo), and producing a bevy of artists, his own records began to slip in sales. When his Buddah contract expired, Mayfield and his partners at Curtom began negotiations with Warner Bros., a larger corporation that promised wider distribution and a lot of Hollywood connections.

The Warner Bros. film connection proved fruitful, leading to his scoring of Sparkle, an Irene Cara vehicle (Cara sang in the movie, though Aretha Franklin sang on Mayfield’s soundtrack record), as well as Let’s Do It Again, which starred Sidney Poitier and Bill Cosby, and featured the Staple Singers on the soundtrack. Mayfield also scored an independent film called Short Eyes, in which he also played a small acting role.

A Lasting Legacy

Though there are gems and minor hits throughout the rest of Mayfield’s solo output, Warner Bros. and subsequent labels were unable to restore his personal career to the level of its Super Fly glory days. And, tragically, in 1990 the musical polymath was hit by falling stage-lighting equipment at an outdoor concert, leaving him paralyzed from the neck down. Though no longer able to play guitar, he was able to sing. In 1994, when Warner Bros. issued the A Tribute to Curtis Mayfield compilation—which featured contributions from Gladys Knight, Eric Clapton, Bruce Springsteen, Steve Winwood, Elton John, B.B. King, Phil Collins, and others—Mayfield was able to contribute vocals to one track. Inspired by the experience, he cut one final record, New World Order. Though he reportedly had to track his vocals one line at a time, while lying on his back, it stands proudly among his body of work.

Curtis Mayfield died from diabetes on December 26, 1999, at the North Fulton Regional Hospital in Roswell, Georgia. His legacy and impact on subsequent music—both in terms of message and musicality—is immeasurable, despite the fact that it’s virtually impossible to be sure which studio records Mayfield played guitar on past the point when he came to be in great demand for his writing, producing, and playing expertise. Still, listening to the dozens of records he was involved with leaves no doubt that, if it’s not him playing, it is someone influenced by him. His distinctive guitar style was always integral to his composing and producing, and it will forever remain a formative and hugely influential part of the sound of soul music.

Hallmarks of Mayfield’s Style

Good luck learning Mayfield licks by watching him on YouTube—that is, unless you know the secret to his tuning. “One day, cleaning out a closet, he’s like 8 or 9, Curtis finds this guitar and sits down on the side of the bed and starts fooling around with it,” Impressions lead vocalist Jerry Butler recalled in a July 2012 interview with The New York Times. “He used to love playing boogie-woogie on the piano, and he learned to play that in F#, which meant he was playing on all black keys. That’s how he came about that unique sound on his guitar, because he tuned it that same way.”

That’s right, Mayfield tuned his guitar F#–A#–C#–F#–A#–F#, low to high. According to Craig Werner’s 2004 book Higher Ground: Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, Curtis Mayfield, and the Rise and Fall of American Soul, Mayfield said, “Being self-taught, I never changed it. It used to make me proud, because no matter how good a guitarist was, when he grabbed my ax he couldn’t play it.”

The Curtis/Live! cover shows Mayfield playing a Fender Telecaster Thinline, while videos from this same time period and later show him favoring ’70s Fender Stratocasters. They also show him strumming or picking the strings with his right thumb and fingers, while curling his left thumb over the neck to play barre chords. The Strat was usually set on the middle pickup. His parts fill out the middle and low end of the tune through a Fender Twin, while lead guitarist Craig McMullen often worked his wah in tandem with “Master” Henry Gibson’s percussion.

Mayfield’s rhythm playing often had a pretty open feel, with the strings ringing out rather than being damped in the tight manner usually associated with funk. Other times he employed more closely muted chucks for rhythmic emphases.

The rolling hammer-ons and pull-offs often used by Mayfield were likely a big influence on Jimi Hendrix. For example: fingering an A at the fifth fret, hammering-on a B at the seventh fret, then quickly pulling it off back to the A, landing on the F# on the B string—all within an eighth-note (see Ex. 1). Of course, the strings and fingering would be different in Mayfield’s preferred tuning.

Mayfield might also play the same rhythmic pattern at the same fret, holding down the A while playing E to F# on the B string and back, landing on the C# on the G string. Straighten out the rhythm and you have a country lick. Play it the way Mayfield played it, and it becomes pure soul.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)