Slavery. Racism. Prison. Lynching. Avarice. Murder. Addiction. Transexuality. Alienation. Deception. Power. These are all themes that Otis Taylor explores in his songs. Also, love and beauty. All within a musical web that throbs to a spare, hypnotic pulse buoying his electric and acoustic guitars and banjos, abetted by flashes of electric violin, the occasional cello or harmonica, and cornet—the latter often made haunting by carefully measured delay. If ghosts listen to music, it surely sounds like Otis Taylor’s.

Yet there’s an undeniable earthiness to Taylor’s method. His lyrics have the bare-boned integrity of a narrative poet, and they are typically inspired by true stories culled from history, news, or the lore of his ancestors. And while his sound is carefully layered and sculpted, it is also a beacon of simplicity.

Taylor has a name for his musical vision: trance blues. But don’t let the “blues” fool you. Unlike most of today’s music bearing that label, Taylor’s songs never become trapped in the amber of 1950s Chicago or Memphis. Certainly the influences of John Lee Hooker, Howlin’ Wolf, Jimi Hendrix, and other past innovators echo within his approach, but his African roots are both deep and more visible, and the psychedelic stardust he sprinkles is timelessness. Taylor also writes about race and social justice in an unflinching manner more akin to hip-hop.

“I have a real Otis Taylor expression,” the 68-year-old original says: “I don’t know much about the blues, but I’m good at being black. That’s what I write about.”

So it’s apt that Taylor’s new release—it’s provocative title, Fantasizing About Being Black, sitting comfortably alongside those of his early discs When Negroes Walked the Earth (1997) and Blue-Eyed Monster (1996)—is an exploration of race. The album begins with Taylor’s guitar echoing cadences of Africa, similar to those found in the playing of Ali Farka Touré or Rokia Traoré, on “Twelve String Mile.” And in “Banjo Bam Bam,” he picks his open-backed signature OME model as his sweet ’n’ burred baritone voice intones the thoughts of a shackled slave slowly losing his sanity. Elsewhere a white Southern congressman conceals his black mistress, interracial couples struggle, and in “Jump Out of Line,” which turns a one-chord arrangement into an Escher-esque soundscape, Civil Rights marchers fret about being attacked.

“The album was finished long before the election,” Taylor explains. “I was thinking about Ferguson and all this stuff with Obama and how the hatred is coming back—that’s why I did the album. Then Trump rolled in. Talk about putting the frosting on the cake.”

Although Taylor got his start at Colorado folk-music institution the Denver Folklore Center, he came of age during the height of the LSD-dappled ’60s and performed in a pair of notable blues-rock bands from the Mile-High City: playing bass with Zephyr and fronting T&O Short Line with his friend, the late guitar legend Tommy Bolin. Dissatisfaction with the business caused him to drop out of music for nearly 20 years to become an art dealer and pro bicycle team coach. He returned at the urging of friends and family in 1995 with his striking sound and sometimes staggeringly dark perspective—which is balanced by a rich sense of humor in conversation—at the ready.

Since then, Taylor has made 15 albums and had songs in such high-profile films as the Mark Wahlberg vehicle Shooter and director Michael Mann’s Public Enemies, starring Johnny Depp as the gangster John Dillinger. He’s also racked up 18 Blues Music Award nominations and taken two home, won five DownBeat readers’ and critics’ poll victories, been granted a Sundance Institute Composers’ Lab fellowship, and won France’s Grand Prix du Disc for Blues. His 2015 album, Hey Joe Opus Red Meat, is on display in the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Premier Guitar caught up with Taylor via phone at his home in Boulder, Colorado, shortly after he’d wrapped up the 2016 edition of his annual Otis Taylor Trance Blues Jam Festival. The event blends education with concerts and open-door performances that find Taylor and his guest players—which this time included Jerry Douglas, who makes cameos on Fantasizing About Being Black—jamming with attendees. “Music is about community,” Taylor observes. “That’s important.” And while Taylor’s music is uncommon, he’s convinced that its simplicity and truthfulness keep it accessible.

You have a singular sound. What are its roots?

The banjo was, and it started for me back in the 1960s. The banjo is like Delta guitar, when you break it down. When I heard those Delta open tunings on guitar after I was playing banjo, it was obvious. That old-timey banjo was so rhythmic, so African, but I didn’t realize it came from Africa until many years of playing.

How did psychedelia enter your music?

From growing up in the ’60s. At that time, you either played funky and psychedelic, like Hendrix, or you did Beatles songs, and I went the more funky, psychedelic route. I never did smoke, drink, or do drugs. I started listening to folk music and then I went to blues. I played blues harmonica, too. And I was listening to Ravi Shankar. Hanging out at the Folklore Center, I heard all that stuff every day after school. Sometimes Elizabeth Cotten would come in, or Reverend Gary Davis. Tim Hardin and Mike Seeger hung out a lot. Between Chicago and L.A., that was the only stop for touring folk musicians. I was 14-and-a-half when I started hanging out there.

How did you discover the Folklore Center?

My mother had a ukulele. I broke a string and said, “Shit, I’m in trouble. I better go get one.” And the Folklore Center was right down the street—four-and-a-half blocks from my house. And, after that first time, I started going there every day. They were really sweet to me: a little black kid coming in during the Civil Rights movement.

What got you interested in banjo?

I saw it on the wall and thought, “That’s cool!” It was an ODE. I got to play one there for a year before I got to buy one. It was $125. That’s a lot of money for a ghetto kid. That’s a lotta shagging balls and caddying at the golf course.

I got excited about it because I heard it there every day. Teachers were giving lessons, people were jamming all the time. It was a magical place. Everybody was welcome.

When did you start playing guitar?

At 16 I bought a Harmony Sovereign. It had high action. It hurt so hard to fret it. I made up these weird beats, like the one on “32nd Time” [from 2002’s Respect the Dead], so I could do a concert just using weird beats, because I could hardly fret. Next I got a Gretsch electric for a hundred bucks because Tommy Bolin was trying to get me to play electric guitar a little bit.

What made you want to play guitar?

One day at the Folklore Center, the Dillards were there and they said I should go down South because I could win a frailing contest. It hit me that’s where they were lynching black people, and I was playing music by people that hate me. So I didn’t play my banjo as much for a while. I became a lead singer in a blues-rock band. There weren’t that many harp players in those days, and I was the harp player in town who could play really good.

My father was a hipster, but he hid it on the inside. He was a pot smoker and loved music. It broke his heart when I didn’t become a jazz musician. That I wanted to play this country blues shit just pissed him off, because he thought people from the country were ignorant—that they stayed down South and got lynched and hated. He had no comprehension how anybody would live in that situation.

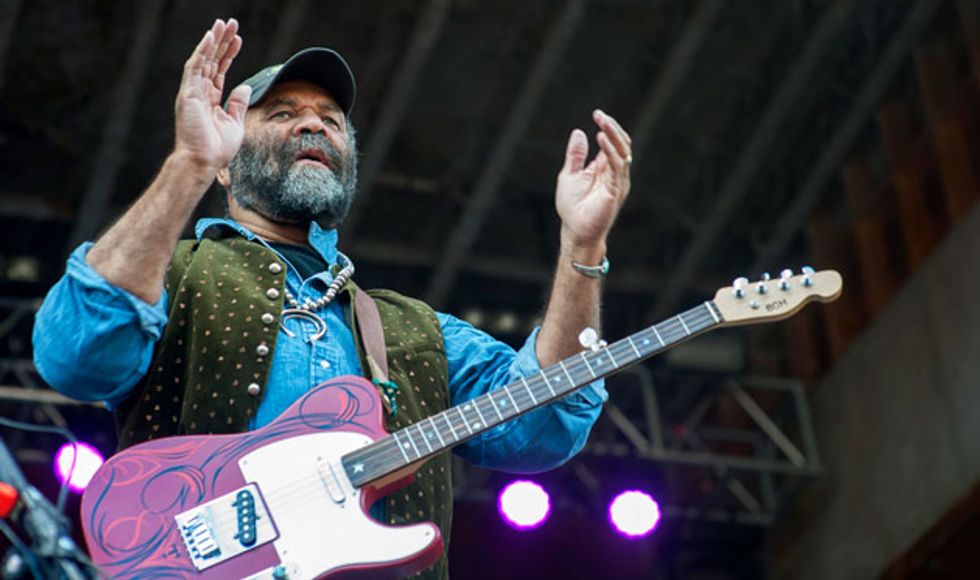

Taylor preaches his distinctive take on roots music at Colorado’s Telluride Blues & Brews Festival with his signature Blue Star Hot Rod Model T Banjoblaster hanging from his shoulders.

Let’s talk about your guitar and banjo technique.

It’s all in the right hand. If you watch a great lead guitar player, like Stevie Ray Vaughan, Hendrix—they’re also killer rhythm guitar players. I played with Tommy Bolin, so I know he was a killer rhythm guitar player. And it’s all in the right hand.

Do you frail or use claw-hammer technique on banjo?

Most of the time, I play it like I play my guitar. I can kick ass on frailing and clawhammer—do it like a white boy! But my approach is more African.

How did you arrive at that?

One day I was sitting around playing, like, a John Lee Hooker thing on banjo. And I realized I had to play a certain beat and not sing that beat. That’s why people don’t do his slow songs: He sings in one meter and plays in another. It makes the slow stuff so eerie, and that’s what I’m interested in. People say I sound like John Lee Hooker, but I don’t sing anything like him. I think that rhythmic contrast is what they mean. Some of my songs have very strange chord changes, but I sing the chord changes instead of playing them.

And sometimes your songs don’t have any chord changes?

Yeah, and they don’t have bridges or choruses—although some do. Howlin’ Wolf did that, too. That approach is African. Everyone who is into blues stops at Robert Johnson or Son House, but who were they listening to? Who played music when they were little kids? Somebody who might have been a slave.

Otis Taylor’s Gear

Guitars

• 1969 Fender Telecaster

• Fender Custom Shop Stratocaster

• Blue Star Psychocaster T-style

• Santa Cruz Otis Taylor Signature H-style acoustic

• Santa Cruz Otis Taylor Chicago H-style acoustic

• OME Otis Taylor 5-string acoustic banjo

• Blue Star Otis Taylor Hot Rod Model T Banjoblaster (electric)

• Blue Star Otis Taylor Hot Rod Mandoblaster IV

• Blue Star lap steel

Amps

• 1965 Fender Princeton (studio)

• Fender Hot Rod DeVille 212 (stage)

Effects

• Seymour Duncan Pickup Booster (studio)

• Mojo Hand FX Rook Overdrive

• Boss DD-5 Digital Delay

• Boss TU-2 Tuner

Strings and Picks

• D’Addario Flat Wound Jazz Lights (.011–.050) for electric guitar, banjo, and mandolin

• OME Heavy 5-string Banjo Strings (.011–.026w)

• G7th capos

How did you know Tommy Bolin?

Tommy was a Folklore Center baby. There was a whole circle of musicians who grew up there. The Folklore Center influenced a lot of people. Bill Frisell took lessons there. Lothar and the Hand People came out of the Folklore Center.

How do you build songs in the studio?

This time I was supposed to do an acoustic album, so I was going to track with the electric and go back over my parts with an acoustic. I got in there and started doing some stuff, and I got the best electric sound I ever got. I said, “This is fucking great! I ain’t changin’ this.” The sound was so great I had a flashback of Howlin’ Wolf—funky, simple, and powerful.

How do you get your guitar sound?

I tell the engineer to give me a little amp that sounds good, and maybe put a pedal on it. I used to do all my recordings with a car stereo amp.

What about your tracking methodology?

Most of it’s a trio with some overdubbing. I often track first, by myself, and when I sing nobody else in the band is there. I start with guitar or banjo, drums, and bass. On the first albums, it would be just me and Kenny [Passarelli] on bass, and later Cassie [Taylor, his daughter] on bass. This time we tracked drums with the guitar and bass, too.

Space is such an important element of your sound.

For this one, I had Larry Thompson lay off the cymbals. It opens things up. You listen to African bands and they’re not hitting the cymbals all the time. All the songs I made all my money off of, like “Nasty Letter” and “Ten Million Slaves” … no drums on those cuts. I got 2-and-a-half-million hits on “Ten Million Slaves” on YouTube. No drums.

For years now, you’ve been producing your own albums. Why?

I started after my fourth album, because the guy who was my producer [Passarelli, who also played bass with Joe Walsh, Elton John, and others] left the band. He asked for a raise and said if he didn’t get one he wasn’t going to play bass and he wasn’t going to produce. I had already gone to the Sundance Institute and had learned about film composing and arranging, so I was ready to go.

I always act like I’m sleeping, but I was really paying attention to what he was doing. And my music is simple—not with complicated horns or string sections. The first album I produced was [2004’s] Double V and it won DownBeat blues album of the year. It had a few little cello parts, but it was really stripped down. As a producer, you find the musicians, you find the songwriters. Well, I was the musician and the songwriter, so I didn’t have to find much.

What’s hard when you produce yourself is if you mess something up, you have to go, “Oh, let me fix this,” right in front of the guys. That’s why I never sing in front of the guys. I don’t feel like a natural-born singer. I feel like a storyteller—like a black Bob Dylan, when it comes to my voice.

I don’t think I do anything really great. I just do Otis really good. I’m not a great guitar player. I’m not a great banjo player. I’m not a great harmonica player. But I’m an interesting songwriter.

Let’s talk about your tunings.

In banjo, most of the time I’m in G minor [G–D–G–C–D], called “mountain minor,” too, where the B [in open G] becomes a C. And sometimes I’ll play in open G [G–D–G–B–D]. On guitar I play in regular tuning and in open G. Dick Weissman showed me my other tuning: D–G–D–G–D–G. He showed it to me on banjo and I put it on guitar. He was in a band called the Journeymen.

Delay is an important part of your guitar and banjo sound. How did you get into it?

[Guitarist] Eddie Turner, when he was in my band, told me, “Oh, you should try delay.” So I got a Boss DD-5 and the first time I put it in this setting, the sound blew me away. The setting is 12 o’clock, 2 o’clock, 12 o’clock, and 5 o’clock. And I can’t get that thing on other delays—only on a DD-5. I have a really good sense of timing. I control the accents and intensity with my right hand.

Do you use the same amp for electric guitar and electric banjo?

In the studio, I play the banjo acoustically. But live I use Fender amps. I like Hot Rod DeVilles, so I can get a little distortion without taking an extra pedal. I like to steer away from pedals. I just use a delay and a tuner. If I don’t have a Hot Rod, I bring a Rook pedal. But I don’t really think about amps technically. In the studio, I just say, “Give me an amp,” and if I don’t like it, it’s, “Fuck this one. Get me another one.” But if it sounds right I don’t say anything. I’m easy until somebody puts something I don’t like in front of me. And it’s always small amps. For this album, they gave me a small amp and put a Seymour Duncan Pickup Booster on it, and I was like, “Whoa, this is it!”

Taylor intended to make his 15th album an acoustic recording until he found an electric sound “so great I had a flashback of Howlin’ Wolf—funky, simple, and powerful.”

You write very precise, spare lyrics that tell emotionally detailed stories. How did you get onto that?

Folk music, man! When I was a kid I learned all these dark cloak-and-dagger English traditional folk songs, and today they tell me I’m too depressing for the blues. What? Aren’t those white people more depressing, with “Pretty Polly” and all? [Sings:] “Oh, he stabbed her in the heart and her warm blood did flow.” I mean, c’mon. That’s where I get that darkness, but also those songs taught me how to get to the point. Dylan used to play that shit a long time ago. I just stayed with it. I have a feeling for doing it. I don’t know why. I am a fan of country and western lyrics. For me to care, you’ve got to bring a story. I think the old-school country songwriters probably got that from the same old-timey shit I did. That kind of storytelling is really a working-class thing—people connect with it. And the blues is like that, too.

Where do you fit into the spectrum? Do you play blues or psychedelia or folk music?

It’s trance blues. The problem with blues is they want to make it like polka music: This is it and it can’t be anything else. There’s a battle in jazz over that, too. To me, the most powerful, living blues going on is hip-hop. It’s trance music, it’s powerful … it’s blues! But they don’t call it blues.

You often write about social justice and race.

I’m black!

I noticed.

Because I’m dyslexic I have a strange kind of memory. It’s more visual. When I talk to guys, especially in England, they can tell you who played on what track on what date on what Vocalion 78. I fuckin’ don’t know that shit. If I knew it, I’d forget it anyway. I forget old blues lyrics except for my favorites. So I don’t know much about the blues, but I’m good at being black. So since I’m black, I must be playing blues music.

You’ve also written about Native Americans; you’ve written some beautiful love songs. But this album in particular focuses entirely on racial identity.

I think it’s important right now. I live in Boulder, and you go to the grocery store and hear people say how depressed they are. I’m in a world of artists and they care about what’s going on.

You often write from a personal perspective—about your mom going to jail, about a long-ago relative being lynched.

Well, I like to write interesting stories and I come from an interesting family. “Three Stripes on a Cadillac” [from 2002’s Respect the Dead] was about a car race in Mexico where they accidentally killed a little girl and had to get the guy responsible out of town. My friend was on the team. So I had to write about that. Or “House of the Crosses” [on 2003’s Truth Is Not Fiction]—I wrote that in Russia when I went on a tour of the House of the Crosses, which is a real prison. There’s some real dark shit. When I get dark it’s so dark that some people can’t get past it.

I’m not here to depress people. Although I can get really dark on albums, I go medium live. Like, “My Soul’s in Louisiana” is about a person getting lynched, but they don’t know that because they don’t listen to the words. They just hear the pretty, catchy tune, so I can get away with it. “Ten Million Slaves” is about the Middle Passage, where 20 million people died on the ships from Africa over 200 years. It’s really a dark song. But I don’t know if people are really listening to the lyrics.

You’ve worked with a series of great guitar players on your albums: Gary Moore, Warren Haynes, Mato Nanji, Daniel Sproul of Rose Hill Drive, and now, Dobro master Jerry Douglas.

I’ve had a lot of “no’s,” too, like Joe Bonamassa, who never got back. And I’ve had great guys in my own band, like Shawn Starski and Jon Paul Johnson. Gary Moore actually came backstage and introduced himself after a gig and ended up playing on three of my albums. I didn’t know who he was. It was just after I started playing music again, so I hadn’t been paying attention. He had these long dreads and looked kinda rough. He told me how much he liked what I did and gave me his number, and then slipped out the back door, so the fire alarm went off. Then everybody in the dressing room was like, “That’s Gary Moore!” So when I called him, I said, “Hey, I fuckin’ hear you’re famous. Want to play on my record?” I toured with him six times. He probably championed me the most.

For Jerry Douglas, I’d met him once in Aspen, and I was trying to get Stanley Jordan to play on the album, but we couldn’t get ahold of him. But at Airshow Mastering in Boulder, [house engineer] David Glasser goes, “I was doing a project with Jerry and told him you were doing an album, and he said he’d love to play on it.”

Why do you gravitate toward strong guitar players?

I gravitate toward good musicians. Larry is great on drums and Todd [Edmunds] is a good bass player. Ron Miles is great on cornet. Anne Harris is an excellent violinist. [Those musicians constitute Taylor’s current band.] Cassie is a great bass player. But people notice the guitar guys.

Let’s talk about your signature Santa Cruz acoustic guitars.

A guy named Willie Carter, who is black, worked for Santa Cruz, and he saw me at the NAMM Show and was a big fan, and he knew that OME banjo did an Otis Taylor model, so he said, “What kind of guitar do you want?” That’s like asking what kind of Porsche do you want—just give me the fucking Porsche!

I talked to Harry Tuft at the Folklore Center, and he suggested getting Madagascar rosewood, because that’s African. So I called and said, “I don’t like a lot of frets, because that’s fancy stuff. I want a Madagascar rosewood H model that’s real thick and just two frets into the body.” And it’s a beautiful looking and sounding guitar. It’s like that old saying in country music: “There’s no money after the 5th fret.” The next version went to Indian rosewood and then to mahogany for the Chicago model. The mahogany has a bluesier sound.

You’ve also got signature banjos: an OME acoustic and a Blue Star electric.

I was at Folk Alliance in Toronto and had a little booth. Pete Seeger walked by and heard me play, and then asked me out for dinner. And we went by the Elderly Instruments booth, and Pete saw an electric banjo and said, “Oh, I think you’d like this.” So I played it and I bought one. But then I was afraid I would lose it, so I called Bruce Herron at Blue Star and asked him to make one for me. And that’s my signature model.

The OME acoustic has an open back. I also play a Blue Star mandolin and a Blue Star lap slide guitar. The slide guitar has a killer sound. The banjo has Tele-style pickups. The first ones they made for me had lipstick pickups. He made me a baritone mandolin, too, but I haven’t played it yet.

You used the Blue Star Banjo Blaster with three chrome-coated single-coils on “Ten Million Slaves?”

ButI leave it on one pickup all the time. I push it away from the front of the neck [to the bridge pickup setting] and I mess around with some knobs.I like the deeper sound. All my pickups, I go back with them.

What did getting songs in the film Public Enemies mean to you in practical terms?

Financially it was a big deal and status-wise being in a Michael Mann film is a big deal. It brought a lot of kids who saw the movie to my gigs—Johnny Depp freaks got turned on to me.

When I play a gig, I can barely get 100 people, but I’ve been in The New York Times and L.A. Times crossword puzzles. I made the top 10 in The New York Times critics’ poll once, and I’m a Sundance fellow—and I still don’t feel like anybody knows who I am. But I can go anyplace in the world and about 100 people will show up. That’s a good start! [Laughs.]

YouTube It

In a live performance of “Ten Million Slaves,” Otis Taylor imparts a brief lesson about the origins of the banjo to an audience at Poland’s Rawa Blues Festival and displays his signature use of delay on his Blue Star Otis Taylor Hot Rod Model T Banjoblaster. His guitar foil is Shawn Starski and Anne Harris plays violin.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.