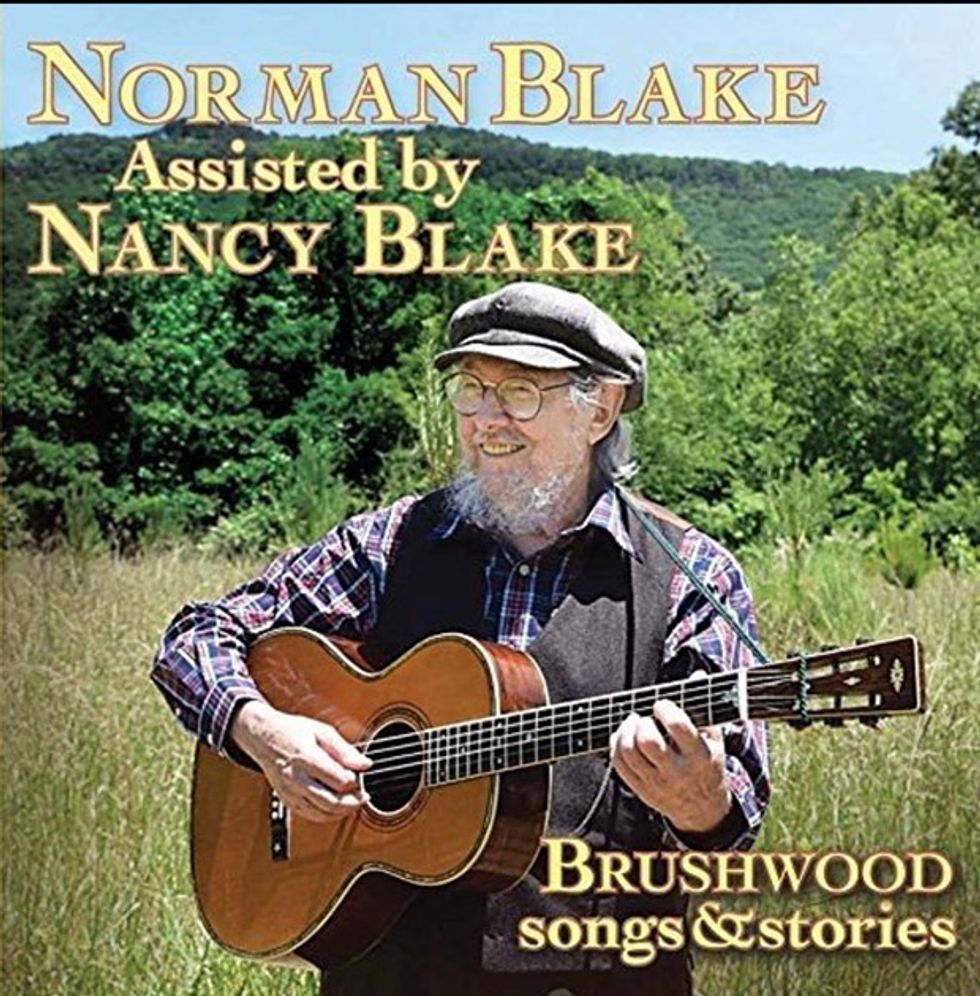

On Norman Blake’s new album, Brushwood: Songs & Stories, the acoustic music legend covers a lot of ground. Over the course of 17 songs and two spoken-word tracks, he shines a light on fascinating lesser-known historical figures, empathizes with the plight of the poor and downtrodden, provides some pointed and timely critique of our current political climate, and takes on Wall Street and the NRA. And as always in the world of Norman Blake, there are train songs.

But what may be Brushwood’s greatest accomplishment is evident within the first 23 seconds of the album, before Blake has uttered a single word. He fingerpicks an elegant intro to the opening track, “The Countess Lola Montez,” and at the 13-second mark, he effortlessly slurs and sweeps through the sort of split-second flurry of notes that makes aspiring guitarists hit rewind countless times, and leaves transcribers scratching their heads as they struggle to notate it. It’s a beautiful musical embellishment by any measure, but what’s most astounding about it—and the album as a whole—is that Blake was 78 years old when he recorded it. He turned 79 on March 10.

Never mind that over the past few years he’s been a more prolific songwriter than at any time in his six-decades-plus-long career. Between Brushwood, released in January, and Wood, Wire & Words, released in early 2015, Blake has recorded 29 new songs that he wrote or cowrote with his wife and longtime collaborator Nancy Blake. This is all material he wrote after suffering a transient ischemic attack (often referred to as a mini-stroke) in 2012 at age 74. In fact, Blake credits that medical emergency with lighting a fire under him and providing a sense of creative urgency.

Not that Norman Blake has anything left to prove. By the late 1970s, he’d already garnered what most would consider a lifetime’s worth of laurels. He’d been a fixture in Johnny Cash’s band for a decade. He’d released several acclaimed albums of his own—among them Back Home in Sulphur Springs, The Fields of November, and Whiskey Before Breakfast. He’d left his mark on several of the most significant musical touchstones in the history of American roots and popular music: Bob Dylan’s revelatory Nashville Skyline, John Hartford’s groundbreaking Aereo-Plain, and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s roots-music masterpiece Will the Circle Be Unbroken. And he’d already amassed plenty of other credits, recording with Tut Taylor, Doc and Merle Watson, Earl Scruggs, Joan Baez, and Kris Kristofferson.

Yet Blake has never shown much interest in slowing down. He’s now recorded about three dozen albums, including a couple of acclaimed duet projects with bluegrass icon Tony Rice. He played on Bill Monroe’s 1981 album Master of Bluegrass. And T Bone Burnett, a huge fan of Blake’s, called on him to play on the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack, including a stirring instrumental version of “I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow.” Burnett also tapped Blake for the Cold Mountain, Walk the Line, and Inside Llewyn Davis soundtracks.

Despite his storied career, Blake has never quite received the recognition many of his peers have. “Doc [Watson] was a revelation,” says renowned bluegrass multi-instrumentalist Tim O’Brien. “He was a real great entry into bluegrass because it was just easy access, the sound of it, his voice and everything. Norman was a little more a connoisseur’s version of that. The record Back Home in Sulphur Springs was kind of mind-blowing. It wasn’t bluegrass, it wasn’t old-timey. It was very old-sounding music, but it just had this ... it was very artful. He always had a real integrity with that. Just a sense of who he was, and his place in time. He was really strutting his stuff back in those days.”

Bluegrass guitar giant Bryan Sutton first became aware of Blake through the duet records with Tony Rice. “My initial response to Norman wasn’t as deep as it is now,” Sutton says. “I was a teenager and was a little more blown away with the fireworks of Tony Rice. But as I’ve grown more into a songwriter and a big-picture kind of guy, and as I got more into the stuff that Norman did in the early days with John Hartford, that just opened up this whole other level of appreciation and recognition of how his musicianship ultimately wins.”

One thing that stands out on Brushwood is the contrast between the old-time music and the very current subject matter of many of the songs. It’s not often you hear such traditional-sounding acoustic music that references social media, Wall Street, the Koch brothers, and climate change. But Blake clearly feels compelled to sound the alarm, and nowhere is this more evident than on “The Truth Will Stand (When This World’s on Fire).” After calling out “fascist politicians and war profiteers,” Blake sums up the state of our nation simply and effectively: “Now wealth and power are ruling our nation/the billionaire brothers and the blood-stained NRA.”

Other songs that address similar issues include “High Rollers,” which takes a hard look at the world of the super-rich; “The Target Shooter,” a direct rebuke of the NRA and the culture of gun obsession; and “How the Weary World Wears Away,” one of the album’s highlights, in which Blake takes aim at greedy developers, climate-change deniers, and the like.

There’s plenty of lighter fare too. On “Bunk Johnson (Trumpet Man),” Blake shares the tale of a relatively obscure but colorful character from the early days of New Orleans jazz, over a buoyant ragtime groove. “Cripple Charlie Clark” is a moving recollection of a musician Blake played with when he was “just a shirt-tailed boy.”

“Waitin’ for the Mail and Social Security” may be the most stirring song on Brushwood. Blake ties together many of his passions—storytelling, trains, old-time melodies, giving voice to those who’ve been crushed under the wheels of progress—as he paints a vivid portrait of an elderly man marking time and reminiscing about what was once a thriving railroad town.

Though Blake’s guitar work shows few signs of age, his singing voice is clearly that of a man in his 70s. But that only makes the music more affecting, and it’s appropriate, since one of the defining aspects of Blake’s career has been his unrelenting dedication to being honest, real, and true to the moment, while refusing to follow trends or succumb to commercial considerations. In fact, all his Brushwood performances were recorded in one take, with Blake singing and playing guitar at the same time. He did some violin overdubs, and his wife Nancy added some lovely backing vocals on several tunes.

Premier Guitar recently spoke with Blake, who was at his home in Rising Fawn, Georgia. He discussed the new album, the state of the nation, and 12-fret guitars (instruments with necks that join the body at the 12th, rather than the 14th fret). He also shared the surprising saga of his experience recording Will the Circle Be Unbroken.

For your most recent two albums, you wrote 29 songs and two spoken-word pieces. You are in your late 70s now. Where did that burst of creativity and inspiration come from?

We spent a lot of time on the road playing, my wife Nancy and I. There was less time to feel creative. We were just working too hard.

We stopped touring in 2007. We’re getting older and everything, and wanted to come home. We’ve always had a place here on the farm. I suffered a little medical thing there about four-and-a-half years ago. After that, it just turned out that way, that I started writing all that stuff. I’d written, of course, earlier on in my career. I guess I just opened in that direction when I had less to do as far as roadwork and all that. And maybe the medical emergency kind of cleared my head into a different direction.

Were there other periods in your career when you had been that prolific as a writer?

No, I don’t think I ever wrote as much in one spurt as I did in the last two or three years.

Obviously, these songs were all written before the election, but they seem even more relevant now. I hear “High Rollers” and I think of our current president.

You can speak freely. You’re not going to offend me. There’s nobody that’s more against him than I am. You’re talking to the choir here.

“The Truth Will Stand” seems to address today’s political situation.

My wife and I are both politically aware, and we’re Democrats, what they used to call “yellow dog Democrats”—we would vote for a yellow dog before we’d vote for a Republican. I’m totally against what has happened. My wife and I both think it’s the worst thing that’s happened to this country in quite a long time. I’m appalled by it. We don’t have enough time. The phone line would burn up before I said everything I wanted to say about it.

For Brushwood: Songs & Stories, Norman Blake took a time-honored approach to capturing his voice and guitar. “I sang all that stuff in one take. I’ve always felt the old bluesmen had the right approach to that. You sing off the guitar, and you play off the singing.” Photo by Christi Carroll

In that song, and “How the Weary World Wears Away,” I sense almost a resignation that humans are going to screw this world up and we just need to make the best of things while we can. Do you feel that’s accurate? Do you have hope for the future?

I always have hope for the future. I am an optimist that things have to get better. I think we were going in a much better direction. It has to get better—the old saying, “This too shall pass.” But it’s a dark time, definitely a dark moment in our history. I hope I live long enough to see it pass. That’s for sure.

Norman Blake’s Gear

Guitars

• 1907 Maurer

• 1928 Martin 00-45

• 1933 Gibson L-Century

• 1937 Gibson J-35

• 1938 Martin 000-42

• 1941 Martin 000-21

• 1960s Yamaha FG-160

• 2004 Martin 000-28B Norman Blake Signature Model

Strings and Picks

Blake typically doesn’t use standard string sets, preferring to mix and match gauges depending on the guitar, situation, and his mood. And he sometimes uses electric strings on acoustic guitars. Though his choice of gauges can vary, he favors .012, .015, .024, .032, .042, and .054 or .056 for strings 1-6. His three main sets are GHS White Bronze, GHS Boomers Dynamite Alloy (electric), and Martin Retro.

He also uses the back edge of his 1.5 mm D’Andrea Pro Plec Teardrop picks, rather than their point, although sometimes he uses a triangle pick and rounds off a corner to make it more like a teardrop’s back area.

I notice trains figure prominently in a lot of your songs, whether it’s “The Fate of Oliver Curtis Perry,” “The Wreck of the Western & Atlantic,” or the story “The Lantern Thru the Fog.” Why is that?

I was raised way down in the sticks here, in Dade County, Georgia, right next to the Alabama line. We had nothing but dirt roads where we lived, and the railroad. We lived very close to the railroad tracks, the Southern Railroad. The trains were the big thing. When I was a child, 22 of them a day ran through here, all steam. We didn’t have a lot of excitement, so the trains figured pretty heavy in it. It’s something I treasure very dearly, those memories.

Is “Cripple Charlie Clark” based on a real person?

Yeah. He had an influence on me. And the first time I ever saw him he was sitting under a tree at the Baptist church, as it says in the song. He was crippled. He had to lean back in a straight chair and stretch his feet out, and he laid the guitar on his knee, the butt-end of the guitar, and the peghead went over his left shoulder, and he strummed it with his right hand, and noted in the usual way with his left hand. He’d make runs up and down the neck, even with his knuckles—he was really messed up physically. He had a sound, and he sang gospel songs.

Did you do some shows with him?

Yeah, and he’d give me money. I was just a kid. I remember one time, I had an old Gibson guitar, a J-45 or something. I had a silver dollar stuck up between the tuning keys on the front of the peghead, just under the strings. We were going to play at a church and he says, “You take that silver dollar off of there. They see that, they won’t give us any money.”

I noticed you included a couple of ragtime instrumentals on the album.

Yeah, I like rags. I’ve gotten to where I play them without any picks. You can do so much more [with your fingertips] than you can with fingerpicks, too.

I’m not using any picks, just bare fingers.

Are you using your nails at all, or just skin?

Mostly the skin. When I’m flatpicking, I use my nails on two fingers to pull harmony notes. When I’m fingerpicking, I suppose I may be getting a little off of the nails, but not like a classical guitar player would.

When recording Brushwood, did you sing and play guitar at the same time?

Yes, and I sang all that stuff in one take. If you’re gonna perform with just a guitar, I’ve always felt the old bluesmen had the right approach to that. You sing off the guitar, and you play off the singing. It all gets to be one thing.

You’re a big fan of 12-fret guitars. Why?

To me they have a more open tone with a little more separation between the strings. I’ve always been kind of clumsy, and a wider neck can be advantageous on the fretboard. It can be not advantageous as far as reaching around the neck.

The 12-fret guitar joins the body at the octave, and I’ve always maintained, though I’ve never heard anyone else say it, that helps create harmonic things. When you have two more frets sticking out there, you haven’t got that octave right on the body. I think there’s some kind of juju that happens when the octave does sit there.

What flatpicks do you use?

I like a 1.5 mm [D’Andrea] Pro Plec. And I use Dunlop some. Sometimes I use the teardrop, and sometimes I use the three-cornered ones. For those, I usually round off a corner. I use the rounded edge of a teardrop pick more than I do its point, but you don’t get as much projection on a microphone. I tend to use a sharper pick when playing on microphones than I would use just sitting around.

Why use the rounded edge?

It just moves through the strings a little easier for me, and it’s a warmer sound, too.You do that on a mandolin a lot, use the back edge. I played mandolin too over the years, and you’re always looking for a warmer tone.

What was your experience like working on Will the Circle Be Unbroken?

I was playing with John Hartford and we’d been off on a tour, and we came into Nashville on a red-eye flight, and I was sick. I had the flu. I went to bed at home, and they called wanting me to come over and maybe play some Dobro, and I said, “I just don’t feel like it.” I said, “Get Tut Taylor,” who was playing Dobro with John and me in the band. So Tut went over there. And they weren’t into what he did or something, so they called me again. By that time I’d gotten waked up pretty good, and so I went on over there. It was with Earl Scruggs that they were going to use me.

Bill McEuen was producing it and in the control room, and kept telling me how to play a certain thing. I couldn’t ever please him, either. He kept wanting something that I wasn’t doing. I got pissed off because I had gone over there and I didn’t feel like it anyway. So I threw the earphones up against the control room glass and told him to go to hell. Earl Scruggs stepped in and told Bill—Earl had that real shaky voice—he says, “Well, if you leave him alone, he’ll play something good.”

So that was how it went down. It was not as much of a fun thing at the time. I’m glad for the experience in the long run. It probably didn’t hurt my career at all.

You did some music for O Brother, Where Art Thou? Apparently T Bone Burnett is a big fan of yours.

He’s been very kind, some of the things he’s said about me. And he used me there. I appreciate him. In artistic ways and financially it’s been good. O Brother was a good thing for us.

I almost didn’t do that. I was living down here where I am now, 140 miles from Nashville. I said, “I don’t want to go over there for a session.” I figured it was just a three- or four-hundred-dollar session, like most of them are. And they finally called me back with a real good figure—“We’ll give you so-and-so to come over here and play”—and I said, “Well, I’ll be there.”

Gillian Welch was helping him out a lot at the time, and I think she might have been responsible for me getting as much out of that as I did. Cuts on the record and all that. I don’t know that for a fact, but I think she was definitely in my corner.

YouTube It

In this 1980 performance clip, the Rising Fawn Ensemble—featuring Norman Blake, his wife Nancy on cello, and fiddler James Bryan—performs Blake’s composition “Randall Collins” and the traditional fiddle tune “Done Gone.” As he accompanies his own singing on “Randall Collins,” notice how his strumming hand and arm stay loose and relaxed. But when he picks a fast single-note passage (see 4:30 for an example), his right forearm barely moves and all the action comes from the wrist.

Blake recorded his newest album at Cook Sound Studios on Lookout Mountain in Fort Payne, Alabama, which is also where he cut 2015’s Wood, Wire & Words.

Gathering Brushwood

When it comes to recording Norman Blake, the old saw “less is more” is the guiding principle, says recording engineer David Hammonds, who helmed the controls for Brushwood at Cook Sound Studios on Lookout Mountain in Fort Payne, Alabama. (The facility is owned by Jeff Cook, lead guitarist for country music juggernaut Alabama.) Hammonds has been working with Blake since 2006.

“We used all Neumann microphones,” Hammonds says. “A U 87 on his vocals, and Norman brought some really old mics—two Neumann guitar mics, those pencil [condenser] mics. It was a pretty simple setup. We used a Universal Audio 1176 compressor and some really cool preamps. We just did a little X pattern with the microphones on the guitar and close-miked his vocal with that U 87. You run into phasing issues like that, but it is what it is. It’s a live setup, and it’s as simple as it can get from an engineer’s perspective. You hit the record button and Norman Blake delivers.”

You might think an old-time acoustic music purist like Blake would prefer recording to tape, but that’s not the case. “We didn’t do anything to tape,” Hammonds says. “It all went down to Pro Tools. Norman seems to think that the Pro Tools rig sounds more like LPs than actual tape does. He’s a connoisseur of collecting the old mono LPs and things like that from back in the day. And he likes the sound of Pro Tools as well or better than tape. We do have tape available.”

When describing what it’s like to record such a renowned musical force, Hammonds’ enthusiasm is palpable. “This guy’s not like anybody else,” he says. “I swear to God I watch him play and I’m thinking, how does he get all that to come out of a guitar at the same time?”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)