When you sit down to talk with many guitar luthiers, the story of how they got into building is often uncannily similar: They fell in love with the sounds of some famous guitar god during their teen years and started playing not too long after that. Eventually they took their first foray into DIY by modding their own instrument, followed by a stab at replicating, say, a Tele, a Les Paul, or maybe some sort of “super strat.” The more they played and tweaked, the more they loved it all, but at some point it hit them that they were better at (or more likely to make a living via) the wood-and-wires side of things than the playing side.

Of course, there’s nothing weird or wrong with any of that. How else would you expect someone to get into it? But when Premier Guitar met Adriano Sergio at the Holy Grail Guitar Show in Berlin last spring, we were immediately struck not just by the uniqueness of his guitars and his approach to lutherie, but also by the adventurous life he led prior to devoting himself to the craft full-time in 2016.

As anyone can readily see, Sergio’s instruments are notable strictly on their own merits: They look like magnificent specimens of living timber summoned from the forests of Tolkien’s Rivendell. That’s probably because he began carving up the family furniture when he was just 4 years old, the ever-curious son of a Portuguese immigrant couple struggling to make ends meet in Paris. Within two years, Sergio’s parents had detected enough passion in their young son to buy him his first real tool set—parts of which he still uses today.

There are solutions.

Fast-forward 46 years, and the proprietor of Ergon Guitars (ergonguitars.com) is back in his native Lisbon, still making his mark on the world with a knife as his main tool. Each of Sergio’s sumptuous instruments is carved by hand, the exact form coming to him spontaneously as he peels back ribbon after ribbon of mahogany, cedar, or swamp ash. As with the alluded-to magical Elven artifacts, there’s also a lot more to Sergio’s guitars than is immediately apparent. Nearly every Ergon model features an intricate hollow interior whose carefully tuned ports are so lovely as to seem merely cosmetic. But the flowing lines aren’t just an artful rendering of form and function with allusions to abstract nudes—though they are indeed that. Although Sergio takes inspiration from the visual arts, film, architecture, and even literature, his meticulous attention to detail serves both structural and tonal ends. Yes, the elegant joining of woods is so cohesive and expertly rendered that it’s difficult to determine where, for example, one dovetailed neck piece ends and the other begins. But Sergio’s neck joints are also so tight and stable that he can string each guitar to pitch—sans glue—in order to fine-tune the instrument’s resonance.

In our estimation, all this seemed like enough to warrant a lovely little film documentary, and yet there’s much more to Sergio’s captivating story. The more we spoke with Sergio, the more we were intrigued. In fact, it was his life that inspired PG to begin profiling builders again after scaling back for a few years. For starters, who would’ve pegged the builder of such head-turning instruments as a former guitar tech for heavy acts like Ozzy Osborne, Anthrax, and Napalm Death? Especially considering he’s actually a conservatory-trained jazz bassist who walked away from a prolific touring and studio career. Oh, and did we mention that he was also the Portuguese equivalent of a U.S. Navy SEAL?

“With every guitar I do,” says Ergon Guitars’ Adriano Sergio, “I get closer and closer to where I want to go. The last one”—the Porto MS shown here—“is really, really close. It has an almost piano-like sound.”

We recently had a lovely Skype video call with Sergio from his shop in Lisbon, where he happily showed off his nearly half-century-old mallet, his first-ever solidbody, and the philosophy driving a budding career in which the affable builder is taking part in projects with esteemed European luthiers such as Ulrich Teuffel, Claudio Pagelli, Michael Spalt, and Nik Huber, as well as displaying his instruments at prestigious gatherings such as Art Fair Tokyo 2019—the latter of which has reportedly never before included guitars.

What got you into building guitars?

Everything started because I wanted to play guitar when I was a kid. Actually, I wanted to play bass, because I have really fat fingers and everybody told me, “You cannot play guitar—you have fat fingers!” I was studying classical guitar, which was a problem having fat fingers [laughs]. When I was 17, somebody gave me a [Fender] Jazz bass neck from ’74. So I decided to make the body. I didn’t know anything about it, but I started to make the body with the help of an old man. I’d been playing with wood since I was a kid. When I say “a kid,” I’m talking about 6 years old. My parents gave me a toolbox with small but quite good tools. I’m actually still using this mallet. I stopped using one of the pliers, like, two years ago. I remember, before that, my parents left home one day, and I started to cut the edges of a table with a knife. I just found it fascinating, the curling wood when you cut it. So I did all around the kitchen table, and I wasn’t happy with that, so I did any corner of wood furniture in the house.

Watch our video interview and demo with Ergon's Adrian Sergio:

I bet they were happy!

They weren’t happy, and I wasn’t happy when they found out. When they came home I was in a panic, “They’re going to find out!” My father was like, “What the fuck is that?” It was a hard time. I come from a really working class family. My father was always doing everything at home—metalwork, woodwork, everything—and I was always watching him.

Let’s get back to that first bass. Did you try to make the body just like a Fender J?

Yes. It looked like Jaco Pastorius’ bass, actually—the same sunburst and everything.Later on, I turned it into a fretless—well, half the neck was fretless, and half had frets. I started to play in bands with that bass. Of course, to play the bass I needed an amplifier. But I had no money, so I made my first amp also. I didn’t know anything about electronics, so I bought a book and put everything together. The funny thing is, I paid somebody to build me the cabinet, because someone told me, “Oh, the cabinet is acoustic. Everything has to be …” whatever. It was a stereo amp. I remember I had problems with distortion a lot of times. I learned so much with that. After that my father bought me a bass, an Ibanez Blazer—which was worse than the bass I made!

Adriano Sergio’s parents gave him this tool set when he was just 6 years old, not long after he’d taken to carving up all the household furniture. He retired the pliers two years ago, but still uses the mallet today.

What happened next in your musical career?

Then it came time for me to go to military service. In Portugal [at the time], everybody had to [serve]. So in 1987 I was selected to go to the navy for two years, and I spent 26 months as a scuba diver and navy SEAL. I started studying jazz when I was still in the navy, at the end of it. After the navy, I worked as a scuba diver for two years and went to a jazz school—the best jazz school we have here in Lisbon. It’s one of the oldest ones in Europe, actually. It’s called Hot Club [Hot Clube de Portugal].

That’s quite a combination of pursuits. Were you a scuba tour guide or…?

I was doing everything you can imagine: cleaning the hulls of oil ships, underwater welding and repair, rescuing bodies, [helping with] movies, teaching people—I even handled explosives. I was earning a lot of money, so I bought instruments and gear, but I wasn’t happy. [Scuba work] was affecting my ears—it was affecting everything.

You mean the water pressure was affecting your hearing?

Yeah. Also, the working environment was not the most healthy for me—the people were rude. I liked to scuba dive, but I was starting to hate it. So I just quit that and took myself 100 percent to music. After that I was really successful as a session player in Portugal. I started gigging professionally, full-time, when I was 23. But after a while I wasn’t happy with the music. I was playing with the biggest upward artists—like, really chic pop—but I hated it.So what I decided was to be a tech. I was really comfortable with guitars, basses, amplifiers—everything—because I never stopped getting into gear. Just like music, I like gear.

What year did you start doing tech work?

My first tour was ’98 or ’99, but I was also playing—just music I liked, though. I started to tour full-time in 2000. That was when I did my first world tour. My first tour was with Moonspell, a Portuguese band, and Kreator, a German band.

Those are metal bands, right?

Yeah. I mainly toured with metal bands. It was 46 days and 46 gigs. No days off.

Wow!

I was in heaven. I was really proud—I was the first Portuguese guy to [do tech] work outside Portugal.

How did you prepare for those tours—did you have to learn a bunch of stuff about amps and effects really quickly?

When I teach people and do workshops and things like that, I always tell people, if you want to learn something and you don’t know it, tell people you know it, and just make sure they will not be able to call you a liar. Just go home and make sure you learn it. That was always my way of life.

Take every opportunity you can, and if you don’t know it, learn it?

Oh yeah. Say yes all the time. Be humble—you have to be humble—but [remember that] everything is possible. I’m not afraid. What I learned as a scuba diver and navy SEAL is that there are no problems. There are solutions.

Compared to the situations you faced in the navy and as a scuba diver, other situations must not have seemed very scary in comparison.

No, but there’s a big similarity—you have to work as a team. A lot of people are afraid to work on teams, because they’re afraid to lose a job. I like to be a team worker. I like to help. Not because I want to take something out of it, but because it’s the only way.

What would you say was one of your biggest lessons from your navy and scuba work?

The moments that had the most impact on my life as both a guitar tech and a luthier happened during the SEAL training course in January 1988. It started with 182 people applying, but only about eight of us got to the end. Every other Friday, before going on leave for the weekend—when there was leave for the weekend—we had to go take a swim. And when I say “swim,” I mean swimming for five or six hours in the Tagus River—from the pillars of the 25 de Abril Bridge back to Alfeite Naval Base. In the cold winter water. After a 42-meter dive. About halfway through, you’ve got tears in your eyes and all you want to do is stop. But the guy next to you would tell you to not give up, to keep going. The same guy, minutes later, would be the one saying he was giving up, and it was your turn to pull him through. We would all struggle through together until we got back to base. The lesson from that that stays with me to this day is the importance of determination, of carrying things through to the end. Also, the importance of shared effort: It didn’t matter if one of us got back alone, but that we all got there together—that we could count on each other, and that we shared the bond of camaraderie. My time in the navy also taught me the importance of being prepared—doing your homework really well—so that when you come across problems you can solve them readily and easily. Basically, the difference between talking the talk and walking the walk. This period of my life also taught me to not be afraid of failure, to not avoid trying something out of fear of making a mistake.

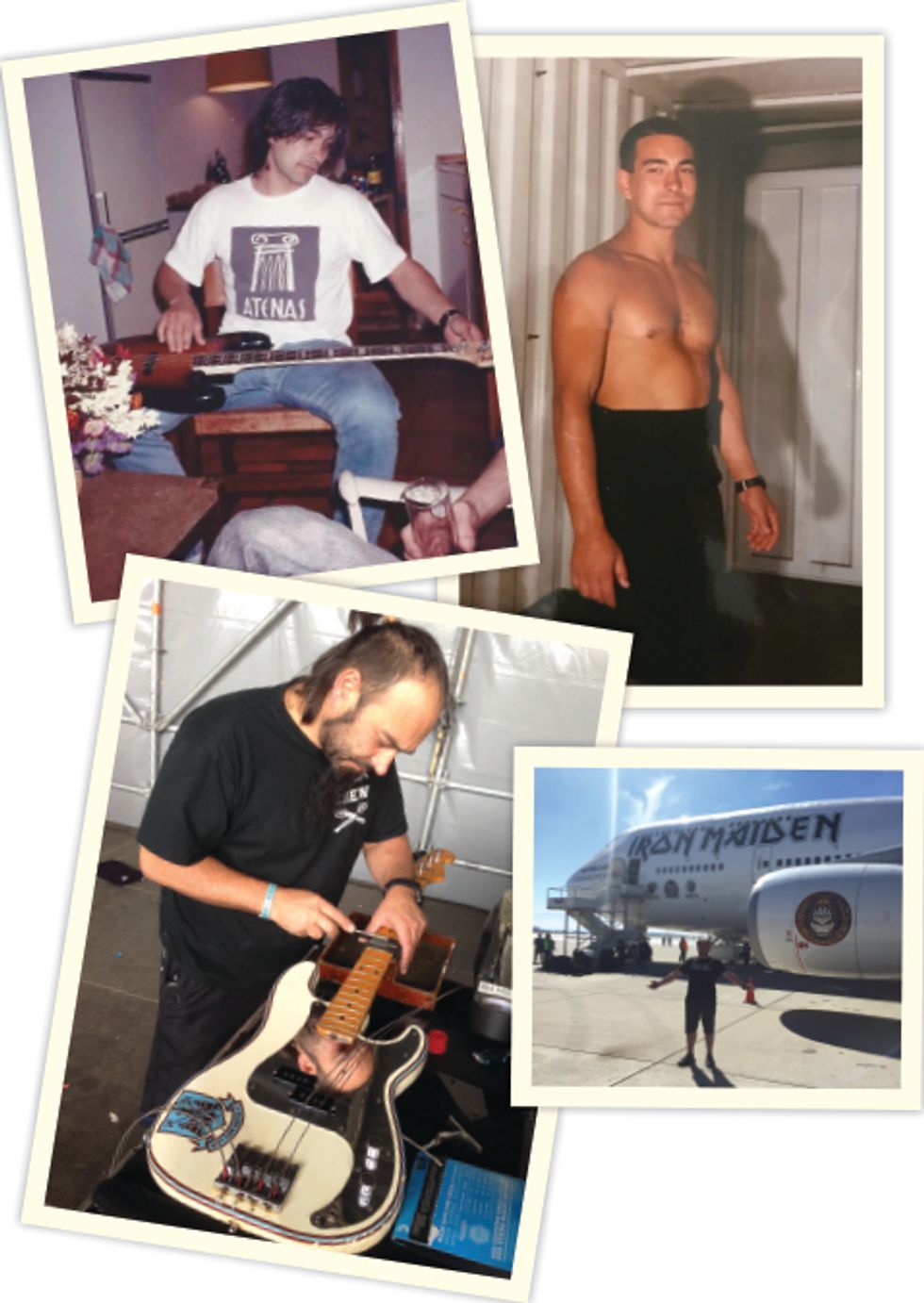

Above left: When he was 17, Sergio received a 1974 Fender Jazz-bass neck as a gift. He soon began work on a matching body modeled after the one played by fusion hero Jaco Pastorius. Above right: Sergio after a scuba excursion circa 1988, when he was a member of the Portuguese navy’s equivalent of the U.S. Navy SEAL team. Lower left: Sergio working on legendary Iron Maiden bassist Steve Harris’ Fender Precision circa 2016.

So being cocky and acting like you’re a badass isn’t the way to success.

You can be cocky if you deserve to be cocky—cocky, but not arrogant—if you’ve proven you’re really good. But you have to be a team worker, too. Being cocky can be because you’re proud about yourself. But a lot of people are cocky because they want to hide who they actually are.

It's interesting you started out as a jazz aficionado, but ended up tech-ing for metal bands.

Metal players really respect the fans, and the fans really respect the bands. It’s why metal is still alive and is growing again. A lot of the bands have a social message behind the songs or the attitude, and I think a lot of the fans see themselves behind that message. If the message changes, they will be disappointed, and they will react.

Did you listen to metal as a teenager?

No, no! Not at all. I started to listen to and respect metal when I started to work in metal.When I got a call to work for Ronnie James Dio, I called my wife and asked her, “Do you know Ronnie James Dio?” She was like, “You don’t know who Ronnie James Dio is?” Of course, after I heard the songs [again], it was like, “Okay, I’ve heard these songs before.” But I didn’t know anything about him. The closest thing I’d heard was Led Zeppelin or Deep Purple. I knew and liked Led Zeppelin, but that’s probably the closest [thing to metal I liked]. I liked a lot of funk and things like that. Do I listen to metal now? Yes. I do with a lot of pleasure—not all of it—but I do.

What was it like working with Ronnie?

I did the last European tour with Dio, which was really good for me. That was eight or nine years ago. Ronnie was a really, really special guy. One day he came over while I was carrying the gear, and he got the snare drum and started to help us. I was like, “Don’t do that!” And he was like, “Don’t tell me what to do, man—that’s my gear! [Besides] the sooner you are done, the more time we have to find out if we like each other.” [Laughs.] That was a great tour.

You also worked with Ozzy and Anthrax, right?

Ozzy, Anthrax, Strapping Young Lads, [Swedish death metal act] Dark Tranquility. My first U.S. tour was Strapping Young Lads, Napalm Death, and Nile. I spent the last two [tech-ing] years with Anthrax and Iron Maiden. I was not [officially] tech-ing for Iron Maiden, but I was doing the setups on Steve Harris’ bass.

As evidenced in the back of this Porto Douro, Sergio’s instruments are inspired by everything from art, architecture, and literature to the human body.

So that was your last tour before dedicating all your time to Ergon?

Yes. Anthrax called me, asking if I could be the backup guy for the tour with Iron Maiden, on the jumbo Boeing plane [Maiden’s custom 747 jet]. Three days later, they fired the main guy. I was already thinking about stopping touring [before that], because I had a [customer] waiting list of seven months or something like that. I ended up paying to not finish the tour cycle, because my waiting list started to be bigger and bigger and bigger. I was not expecting the tour to be that long, and I wasn’t enjoying touring anymore. I wanted to do my guitars—I wanted to be full-on. Ergon Guitars was growing fast.

So when you were on the road, you were also taking orders for Ergon guitars?

When I was with Strapping Young Lads, this is around 2001 to 2004, I started a guitar repair shop called Guitar Rehab. Actually two—one in London and one in Lisbon. Nowadays I only have my Guitar Rehab Lisbon. I haven’t done repair in six years, but I have a team of four guys [who run that shop]. I always thought, “Okay, if I don’t like touring, or if I break a leg or something like that, I need a plan B.” Later when I was touring, yes, I was also building guitars. The two last U.S. tours I did, I would take my four days off to fly back to Portugal and build guitars for two days, because I needed to build guitars for NAMM or another guitar show. Also, I couldn’t stand to be off for three or four days, doing nothing, because my brain was here. My brain was always on my designs.

So you went to building full-time…

Two years ago now.

What’s one of the standout moments from your time on the road?

I was with DragonForce as guitar tech for Herman Li on [2015’s Full Metal Cruise], and weeks before that he had broken the headstock of his main guitar during the South American tour. He wanted to use that guitar to play a solo in the swimming pool. So not only did I have to improvise and superglue the headstock, I had to wrap, seal, and waterproof everything from the electronics to the wireless system using whatever I could get my hands on—latex gloves, condoms, whatever. It ended up shredding to the end. Just like during the navy days, there are no problems. Only solutions.

When did the ideas we see in the Ergon line start to take shape?

Since the first guitar. When I decided to make my own guitars, there were two things on my mind: I will not copy anybody—I learn from everybody, but I will not do something that has already been done—including by myself. I will not stick on my own ideas. That’s why I don’t use templates. I will not allow anybody to tell me, “That’s my idea!” That was one of the rules. Another rule is I’m going to try to make guitars that are not easy to be made by machines, by CNCs. And they are not, because I don’t make them from a template. Each guitar is the evolution of the previous one. It’s too much work for somebody to work with a CNC and change everything all the time. It doesn’t make any sense.

So you don’t use computers for anything except regular business stuff—e-mail, bookkeeping, etc.

No, not at all. The way I build my guitars, when it’s a new model, I do a prototype in hard foam, like surfboard foam, like they used to do with cars. I shape them and test them physically, because I can cut them and carve them in like 20 minutes.

What inspired that approach?

I really like art. I studied art in school when I was a kid. I’m really into painting, sculpture, cinema, books. I like shapes. I like nature. Also, as a bass player, basses like Warwicks and Spectors started to bring different shapes and contours back. For me, it was like, why don’t they do that on guitars? That was the first spark.

When I started to build guitars, I always respected the big brands. Fender, Gibson … all the big brands gave us the main guidelines—like, where to put the neck. All the experience I got using those instruments through all those years on tour, I use all of that with my guitars. And then I just try to make them more comfortable. Not only visually, but physically, also. It’s why I chose the name Ergon. It’s Greek. “Ergo” means “work” in Greek, and “nomos” is “nature.” It’s a relation between the work and the nature. I was also inspired by other peoples’ work—Rick Toone, Saul Koll, Pagelli, Ken Parker, Thierry André, and Michihiro Matsuda.

Can you talk about the intersection of the visual/ergonomic and the aural aspects of your guitars?

I really like the furniture of [Spanish modernisme architect Antoni] Gaudí. For some reason, everything I do with my hands goes to there—everything just tries to flow. Sound-wise, it’s another thing: I don’t want to make a guitar that looks the way it looks and then sounds like other guitars. I don’t want to make just an electric guitar or just an acoustic guitar. I want to make an acoustic guitar with an electric sound, and an electric guitar with an acoustic sound. Basically it’s an acoustic-electric guitar with a lot of air inside. With every guitar I do, I get closer and closer to where I want to go. The last one is really, really close. It has an almost piano-like sound.

Much of the hardware on Ergon Guitars, including tailpieces and rear cavity covers, is made from pieces of drum cymbals carefully fashioned to match each instrument’s unique contours.

You use traditional magnetic pickups, but do you also have internal mics or transducer pickups?

No, I never have. I’ve been using mainly two brands of pickups with alnico and neodymium magnets: Ezi Pickups, from Israel, and Häussel Pickups, from Germany. Lately, I’ve just been using Häussel pickups, the alnicos. I asked [Harry] Häussel to build me six different prototypes. I told him more or less what I want, and I told him I don’t want to know what he’s going to do. I just want to have six different pickups here. So every guitar I do, I test those six pickups, and I choose the ones I want.

What did you ask for in those six pickups?

I wanted a staggered humbucker where, on the three lower strings, the pole pieces were closest to the bridge, and on the higher strings, the rails were closer to the neck. I also want pole pieces with a 12" radius, which is mainly what I use on my fretboards, unless a client wants something else. When I went there with a guitar, I was like, “Do you want to hear my guitar?” and he’s like, “No—there are other pickups in there.” Then he played it acoustically and we worked from there. I loved that. We tried to find something for the sound of my guitars through the ears, not through the numbers. Not through the rules. It’s the same way I build my guitars: I build my guitars tapping the wood. I carve them tapping the wood. Each piece of wood is thinner or thicker, depending on the kind of wood I have. My neck joint is pretty much the same [on every guitar], but [the thickness of] everything up to the fretboard depends on what I want from it. I build guitars with my ears, not with my eyes. Harry does the same thing, and then he replicates the pickups every time the same. I love that.

Can you tell us more about the neck joint?

I do a slide-in dovetail style with a long tongue … or not. It depends on the wood and the attack I want. That way I have a better meld between the sound of the neck and my body. The reason I came to that result was I was insecure to make my neck joint in a traditional way, considering all the carving I do on my guitars. I wasn’t sure how steady it was going to be, and I wasn’t sure, sound-wise, what would happen. Doing it that way, my neck actually keeps my top and back together without using any glue—I can put strings on my guitars without gluing my necks. I’m shaping my instruments with strings and playing it until I decide, okay, it’s time to stop [carving] and start sanding. Most of the time, I do that without gluing the neck.

Is that so that you can hear how resonant it is or feel how comfortable it is to play?

It’s about the sound, and it’s a lot of work. Some people tell me it’s crazy—“You cannot hear the difference,” or “You waste a lot of time”—but from my point of view, if I start to think, okay, I need to stop listening to save time, then I’m not going to keep improving my guitars.

Most of your guitars have chambered bodies, right?

Most of them are very, very hollow. You can almost see the braces—which are carved out of the [body] wood, actually.

Are most of your clients into a particular type of music?

Not metal [laughs]. I have, like, one or two metal guys. I think my clients are more bluesy, jazzy, open-minded musicians.

One of the most stunning demonstrations of Sergio’s woodworking prowess is the seamless, supple beauty of his often-undetectable slide-in dovetail neck joints.

What woods do you use?

I use mahogany for necks and bodies. A lot of Spanish cedar—I bought a big stock of really old Spanish cedar. I use Canadian cedar, Spanish cedar, Brazilian cedar. Swamp ash for solidbodies. I got some lacewood lately, too. Flamed maple for some tops. I use ebony, blackwood, Indian rosewood, and some reclaimed Brazilian rosewood for fretboards. All my wood is [Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, aka CITES-] licensed.

What’s the range of prices for your instruments?

The average is between €6,000 and €6,500. In dollars, that would probably be about $7,000 to $7,500. The lowest price is €4,500, so $5,000. That’s for my only solidbody, the BT.

Other than your first solidbody guitar, you don’t really seem to have tremolo-equipped models.

People don’t really ask me, except for that one. Actually, I’m going to have one—I have an order for one from the U.S. But if people don’t ask me, I don’t use tremolos.

Is it trickier, structurally, to work around?

Yeah. It messes with the acoustics. I’m working on it. That’s the thing, though—I’m learning with each guitar. If I make radical changes, then I don’t know why it sounds so different. But if it’s a custom order and the customer wants something [radically different], then I have to rethink it all and it’s no longer really as much of an evolution of my previous work.

You typically interview clients as part of the order process. What do you usually ask?

All sorts of questions. We, of course, end up talking about music, but I want to know everything about them. Taste in food and books. If they play games, which kind of games. Movies, holidays, which kinds of things they like and don’t like. Personal things they want to share. If they have any preference of guitars or guitar players. The more information they want to give me, the better. It helps me to understand them when they talk about what they want in their guitar. Also, what I would like to offer in my guitar price is to have them travel here and stay with me. If they can’t, we do Skype interviews.

After the interview, do you brainstorm a body shape, carve it out of foam, and send them pictures, or do you actually send the foam cutout to them?

I just show it through the Skype. I never show drawings. Nothing’s 2-D. It’s always a physical thing.

Are most of your guitars custom orders?

It’s half and half. But most of my custom orders are from the models that I bring to [trade] shows. There are exceptions where people ask me for something different, but I’m starting to be more and more careful about the orders. A lot of times people ask for things they think they know they want, and I have to be careful to make sure that they really know what they are asking. Because I take a big risk: When I accept an order, I tell the clients if they are not happy, I will make them another guitar. When I send out the guitar, there’s a lot of tension—until I get the “Yes, I’m happy,” I get nervous. I get really nervous.