Türk halk müziği—Turkish folk music—is an ancient blend of odd meters, microtonal scales, and unique timbres. To informed ears, it resembles other Balkan and Mediterranean folk styles, Sufi devotional music, and the classical music of the Ottoman Empire. Meanwhile, its lyrical themes are often ambiguous and interpretable as having religious and secular meanings. But it’s a distinct form, and, depending on your tastes, can be addictive.

At least, that’s what a trio of Dutch musicians—bassist Jasper Verhulst, guitarist Ben Rider, and drummer Nic Mauskovic—discovered during a stop in Istanbul while on tour as sidemen with baroque-pop multi-instrumentalist Jacco Gardner. That trip wasn’t their first exposure to Turkish folk music, but it lit a spark that soon became an obsession, and when they got back to Holland—and Gardner put his live band on hold—they decided to give it a try.

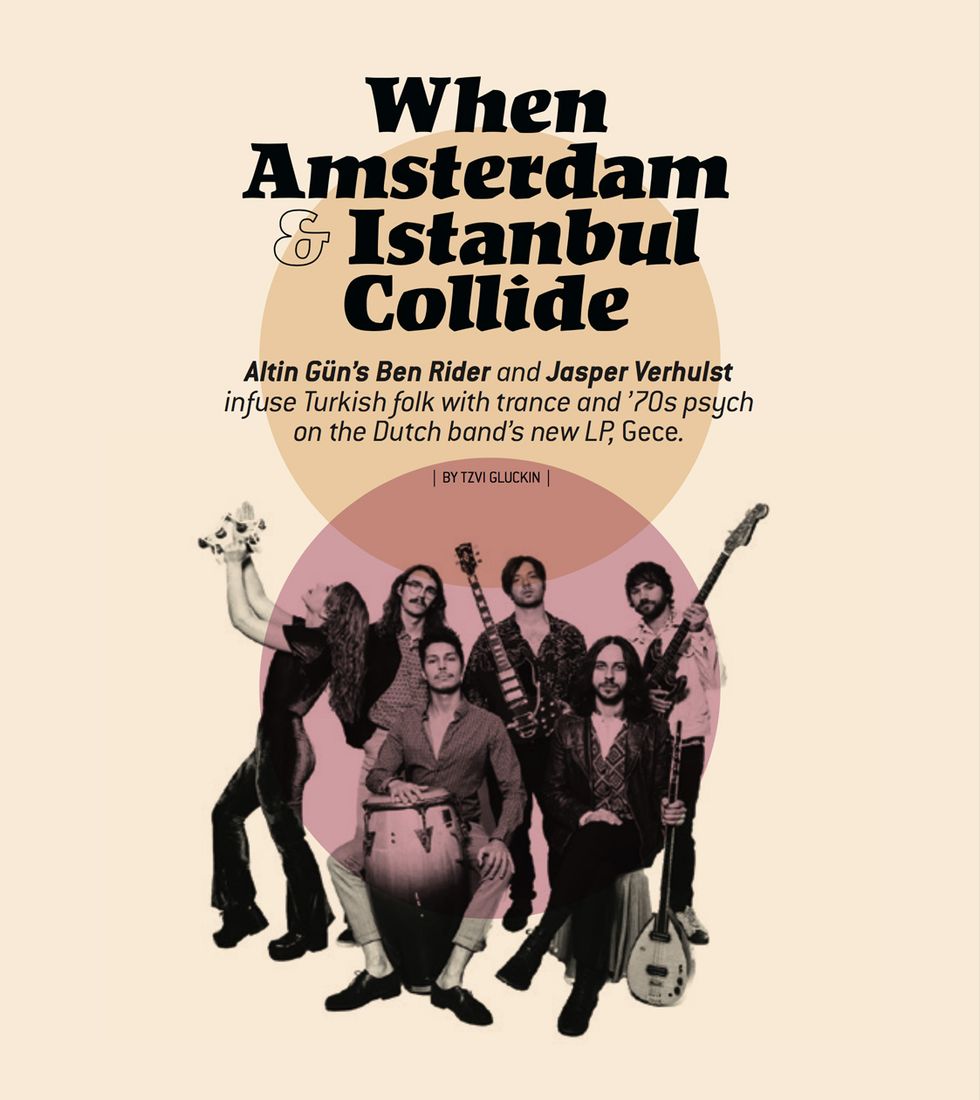

The result is Altin Gün (Turkish for “golden day”), their post-Gardner, early-’70s-inspired psychedelic take on Turkish folk. To complete the picture, the three bandmates recruited Turkish-speaking vocalists Merve Daşdemir and Erdinç Ecevit Yildiz (who also plays synths and electric saz, a lute-like traditional Turkish instrument) via a Facebook post, added percussionist Gino Groenveld, and released their debut, On, in 2018. (Mauskovic left soon thereafter, and Daniel Smienk is the band’s current drummer.)

Altin Gün’s repertoire is almost exclusively covers drawn from modern Turkish folk masters and centuries-old standards. But their music is also infused with a heavy dose of trippy textures and grooves. It’s those seemingly disparate elements—the quirky feel and non-Western tones of traditional Turkish folk combined with vintage fuzz tones, warm synth sounds, and a dreamy reverb sheen—that give the band its edge.

Gece (pronounced gee-jeh, meaning “night”), Altın Gün’s sophomore release, builds on that concept. The album contains tight unison lines played on guitar and electric saz over a throbbing pulse, like on the opening track, “Yolcu,” but also songs like, “Ervah-i Ezelde,” which features a psychedelic warble in 7/8. But don’t think “7/8” in the Western sense. As we explain in the accompanying “A Turkish Folk Music Primer” sidebar, that 7/8 feels like 2+2+3—one of the quirks that makes it danceable and engaging.

Verhulst and Rider have a deep grasp of Turkish feels, but their approach isn’t schooled. They’ve acclimated to it all completely by ear. “If someone said, ‘Play this in 7/8,’ I would have no idea what to do,” Rider says. “But once I hear it, then I can feel it and do it.”

We recently spoke with Verhulst and Rider before soundcheck for their sold-out show at Barby in Tel Aviv. We talked about their no-frills gear, their strictly analog recording approach for Gece, and the tricks Rider uses to play in tune with an electric saz.

Who were some of the artists that triggered the core trio’s love for this music when you were first playing in Istanbul with Jacco Gardner?

Jasper Verhulst: It wasn’t necessarily that we discovered artists while we were there. I was already listening to some Turkish artists, but after I went there it triggered something in me. I became more passionate about digging deeper into the history of Turkish psychedelic folk music from the ’70s.

TIDBIT: No Pro Tools for Altin Gün. The group’s new album was cut on an 8-track tape machine with a complement of analog gear including old echoes, tape recorders, and spring reverbs.

Ben Rider: We already knew the main artists, like Selda Bağcan, Erkin Koray, and Barış Manço. We had heard those names and their music before, but that trip inspired us to get more into it. We’ve discovered loads of artists since then. The main one is called Neşet Ertaş. He’s a saz player and we play a few of his songs. Verhulst: He’s a folk artist who’s been covered a lot by Selda Bağcan, Erkin Koray, and also by us. He is from the area where our saz player [Erdinç Ecevit Yildiz]’s parents are from.

Is your repertoire mostly traditional music?

Verhulst: It is only traditional music. On the new album, we have one improvised spoken-word thing, “Şoför Bey,” but the rest is all standards and traditional tunes. We play songs by Neşet Ertaş and Âşık Veysel, but also songs with unknown composers.

How do you choose the songs—are you looking for an adaptable melody or a certain type of groove?

Rider: A good melody and something that strikes us, like a passionate way of singing it. But Jasper is the one who mainly does the digging.

Verhulst: Yeah, like a good hook. But it’s me and Erdinç. He grew up with the music and I am a record collector. That, combined, leads to most of the options we present to the rest of the band.

Rider: Sometimes it doesn’t work. We’ll try it and it doesn’t really groove, and then we’ll just go to another song and that will groove. It’s always a process. It’s not like, “This is the song—we’re going to do it, and that’s it.” It’s all trial and error.

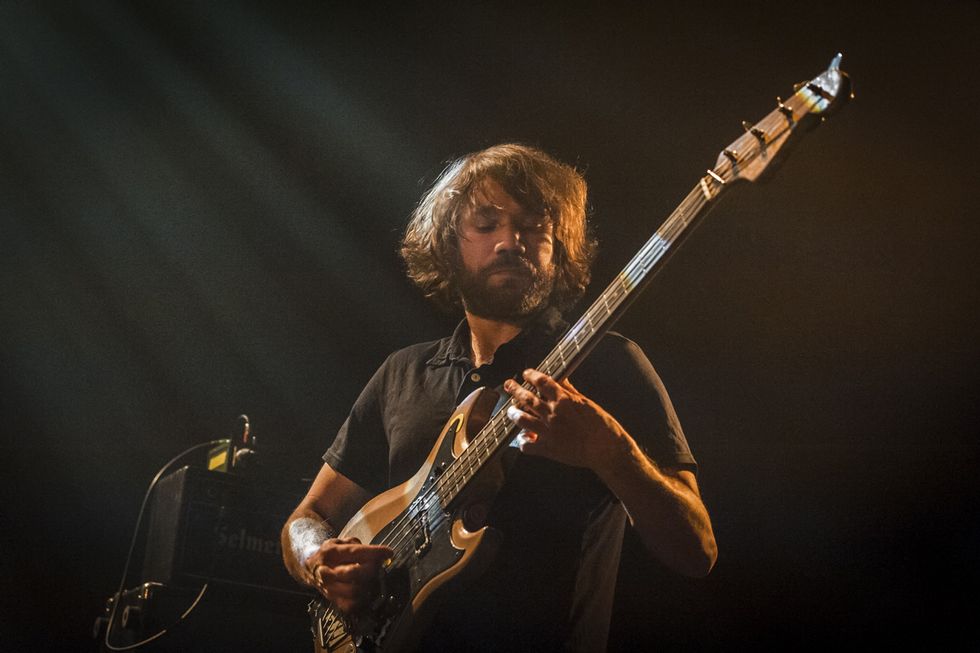

Jasper Verhulst’s bass of choice is a vintage Hagstrom that’s all original except for the bridge and the finish, which has been sanded off for a natural wood look. He plays with .73 mm Dunlop Tortex picks. Photo by Mylène Pinelli

How much time do you spend working on arrangements?

Verhulst: Sometimes it’s instantaneous. We decide this song might be cool, give it a try, start jamming on it, and the arrangement is instantly there.

Rider: But we sometimes change it around until it gets good. There’s a song on the first album, “Şeker Oğlan,” which we’ve now completely rearranged again. I actually prefer the version we’re doing now compared to the one that’s on the album.

Why?

Verhulst: It’s easier to play live. The album version was more like an electronic experiment. We did it all on click, with a lot of copying-and-pasting. Now we’ve made a version that works organically as a band.

Aside from the saz, your instrumentation is basically standard rock ’n’ roll. Do you use vintage instruments? And what are you doing to get those ’70s-era Turkish psych sounds?

Rider: We adapt to whatever the song might need. We do use some old instruments. Jasper’s bass is from the early ’70s, and my guitar is as well. We’re using old fuzz pedals, like a 1968 Schaller Fuzz, and I’ll use a wah pedal to make those nasal sounds. Listening to those old records, there’s some weird tones, some really strange sounds, and sometimes we try and get that by freaking out with effects pedals.

What’s an example of that?

Rider: I often use the wah, left at one position and going into a fuzz, to get the lead sounds. I use an Xotic AC Booster to make thicker tones—when you boost the bass on the AC, it makes the Schaller Fuzz go all crazy. The AC is also great for a little gain, especially when I use the neck pickup with the tone rolled all the way down and the bridge pickup with its tone on full. You get these great nasal tones similar to the lead guitar in the song “Ince Ince Bir Yağar” by Selda Bağcan. The [Electro-Harmonix] Small Stone phaser is an important part of my rhythm sound, combined with the Xotic SP compressor—which is pretty much always on—to keep levels fairly constant and to add a bit more attack, which is great for the funky bits. I also often make swells by holding the left switch on my Strymon [El Capistan] delay, which puts the feedback on full until you let go.

Basses

1970s Hagstrom HIIB

Amps

Selmer Treble ’N’ Bass 50-watt head

Ampeg 2x10

Effects

Ibanez AD9 Analog Delay

Fulltone ’69 MkII

Strings and Picks

D’Addario XL Half Rounds (.050–.105) sets

Dunlop Tortex .73 mm picks

Verhulst: We also use late-’70s synthesizers. And when we were recording the album, we only used analog for delays and reverbs, and we recorded it directly to tape.

All to tape—no Pro Tools, nothing?

Rider: Eight-track tape. Our sound guy, Jasper Geluk, has a studio called Tone Boutique where we went to record the album, and he had a bunch of old echoes, tape machines, and spring reverbs. But no computers. No Pro Tools. It was all the way they used to do it.

Do you show up well rehearsed and lay it down as-is, or do you do a lot of overdubbing?

Verhulst: We did a couple synth overdubs and vocals, but the rest is basically live.

Rider: You can hear that there’s a mistake here and there, but that to us doesn’t matter at all. It’s about the feeling. If the groove is good, then we take that take. Sometimes you’ll hear my fuzz pedal being clicked in or something. It’s not polished, but that’s not what we’re going for anyway. To prepare for this album, we rented out a place—a small cottage in the countryside in Holland—and spent a week together, playing and rehearsing new ideas. We had a whole bunch. We didn’t end up using all of them, but the ones we chose we did rehearse as much as we could. In the end, you always end up doing something different in the studio, especially being inspired by the sounds that you’re using. For example, I went straight from my guitar into the input of a German tape echo, a Dynacord Echocord Mini—not using the echo part, just the preamp—and going straight into the [recording] desk. It made a certain sound that inspires you to play a certain way.

Jasper, your bass looks like a bit of hybrid. Were the neck and body from different instruments?

Verhulst: Only the bridge is not original, although the color is not original—someone shaved it to the natural wood color. The body and the neck belong together. It’s a Hagstrom—I don’t even know the type. [Editor’s note: Based on photo evidence, it appears to be an HIIB.]

And Ben, your guitars are an Epiphone Casino and a Gibson SG?

Rider: Actually, that’s Jasper’s Casino. I just borrowed it. But now I’ve got my own guitar, which is an Aria SG[-style]. It’s a Japanese, pre-lawsuit guitar from the Matsumoku factory from around 1974. It was made with a lot of care and love. You can feel that it’s good wood, good pickups, a good tremolo. I was actually going for a real Gibson SG, but they are way too expensive, and I don’t know if it’s worth it. This one I found online, like on a thing similar to Craigslist, but in Holland.

Is it stock or did you modify it?

Rider: I changed the electronics so one of the tone buttons is a push-pull that activates different combinations of the pickups. I’ve got more pickup combinations, so if you play around with the tone on one pickup, it will keep the tone on the other pickup, and you get this weird nasal, phase-y sound, which is great for the type of music we make. Especially with a bit of gain on it, it sounds like one of the Selda Bağcan guitar sounds.

To play in tune with the saz (a lute-like traditional Turkish instrument), Ben Rider tunes his Aria double-cutaway’s 3rd string to a note between C# and D, and the 4th to a note between G and G#. Photo by Mylène Pinelli

The Turkish rhythms you play are often in odd meters or use various polyrhythms. Can you explain how the rhythms work?

Rider: No, we have no idea what we’re doing. Some of the songs are 7—I know that for sure. There’s a B-side we did, which has a 5/8 and a 7/8 in the same song. It keeps changing. But to be honest, I haven’t studied any of this, and it’s just a feeling. I don’t think any of us are actually counting.

Verhulst: If the melody is good and it’s catchy, I can just remember it. I don’t need to study the rhythms, it just makes sense.

So it’s all intuitive. You hear it and play it.

Verhulst: Gino Groenveld, our percussionist, and Erdinç have studied music, and they really know their rhythms. They can do complicated stuff from the top of their heads. Ben and I are more musicians that need a melody and need to understand and feel the song first before we can play something like that.

Rider: If someone says, “Play this in 7/8,” I would have no idea what to do. But once I hear it, then I can feel it and do it. “Ervah-i Ezelde,” from the new album, is in 7/8. We have other songs that are in 6/8.

How about scales and microtones. The saz uses a different tuning system than a guitar. How do you approach something like playing unison lines together?

Rider: I detune the strings. The [4th] and the [3rd] strings, I detune them down, so I’ll be able to play along with the saz. I can still play rhythm on the low notes with normal tuning, or solo with the high strings. But the ones in the middle I use to get those microtones.

Do you leave your guitar like that the whole set?

Rider: I keep changing it, every song. Most of it is in standard tuning—I do a lot of rhythm parts—but when there are solo parts that are unison with the saz, then I need to play those microtones. Otherwise it sounds really out of tune. I mean, microtones sound out of tune to us anyway, but if the guitar and the saz are playing two slightly different notes, it sounds really ugly. That’s how I try and fix that problem, but there are other ways. We were in Australia with King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard, and those guys have guitars with extra frets, so they can play those microtones. I was thinking that maybe I should do that, too, but I am not that far yet.

Guitars

1974 Aria SG-style solidbody

Fender Jaguar

Gibson SG Faded

Amps

Fender Hot Rod Deluxe

Effects

Dunlop Cry Baby wah

Xotic SP Compressor

Xotic AC Booster

1968 Schaller Fuzz

TC Electronic Rusty Fuzz

Analog Man Peppermint Fuzz

Electro-Harmonix Small Stone

Strymon El Capistan

Electro-Harmonix Nano Holy Grail

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010–.046) sets

Dunlop Tortex .73 mm picks

TC Electronic PolyTune

Korg Pitchblack Mini (for fly gigs)

So, on the microtone songs, your tuning is standard tuning, except for the 4th and 3rd strings. How do you tune those?

Rider: I tune the [4th string] to between a C# and D—so the indicator on the tuner won’t be in the middle, it will be on the side. For the [3rd] string, I go up to between G and G#.

And then it’s just a question of hearing it and hoping for the best?

Rider: And playing around it—it’s quite awkward to play sometimes. It is a bit of fiddling around, but once you get the feel for it, it tends to work out pretty well.

Jasper, is your bass in standard tuning, or do you detune it as well?

Verhulst: It’s in standard. In most Turkish music, the bass doesn’t usually play quarter-tones. Usually, Turkish music has no bass at all.

So you have free rein to do what you want?

Verhulst: Basically. The songs we’re playing, there’s usually not an original version—they’re folk songs. If there is, it’s usually just a guy with a saz, playing pretty drone-y. He plays something that’s like a theme, and then he sings over the drone, and then plays the theme again. We have a lot of freedom to do something completely different with those songs.

It looks like you always use a pick. Do you find that works better for this type of music?

Verhulst: I play almost everything with a pick. I never had any bass lessons and this is the way I taught myself to play. I really like the sound, too. Although in quiet bits, I do use my fingers sometimes.

Turkish music also has a spiritual dimension and is sometimes associated with the Sufi tradition. Have you looked into that?

Rider: Our singers were brought up with this music and are definitely part of that spiritual side. We’re the Western side of the band. Mixing it up makes it interesting.

Verhulst: We also don’t speak a word of Turkish. We only know how the music makes us feel. We don’t really know what it means or what the history is behind it. We go with our feeling.

Strains of pop, folk, and psych-rock ricochet through this 2017 Altin Gün performance at the Halle de la Courrouze in Rennes, France.

Altin Gün’s visual style telegraphs their devotion to ’70s psychedelic folk music as much as their music does. Band members are, clockwise from left to right: Gino Groeneveld (percussion), Nic Mauskovic (drums), Jasper Verhulst (bass), Merve Dasdemir (vocals), Erdinc Ecevit Yildiz (vocals/ keys/saz), and Ben Rider (guitar). Photo by Sanja Marusic

A Turkish Folk Music Primer

Altin Gün’s music is a ’70s-psychedelic take on Turkish folk music. Similar to Ottoman classical styles and Sufi devotional music, Turkish folk music has been around for hundreds of years. It’s based on strong, long-standing traditions, and has an established approach to rhythm, timbre, and pitch.A Turkish time signature, or meter, is called an usul—but that doesn’t mean a time signature in the Western sense. Rather, an usul also spells out specific subdivisions plus larger time divisions. “For example, a simple usul would be 9/8,” according to Gabriel Marin, guitarist in the Middle Eastern fusion band Consider the Source. He’s been performing with a Sufi order for more than 10 years. “But it wouldn’t just be 9/8. It would be specifically 2+2+2+3—an usul that is very common in folk music. In Ottoman classical music, the usul is much longer—it could be 28 or 54—but that doesn’t necessarily mean 54/4. Rather, it’s all these smaller subdivisions and the places where you put a strong beat and a weak beat. The composer Béla Bartók did a lot of transcriptions of Hungarian, Balkan, and Turkish folk music. Sometimes he would write “7/8,” but then in parentheses he would write “2+2+3,” because that’s very different. A folk dance in 5 that is 2+3 is different from one that’s 3+2, because the dance step is a different dance step.”

A scale in Turkish music is called a makam. But similar to an usul, a makam contains a lot more information than a typical scale in the Western sense. A makam also indicates direction (as in descending or ascending), strong or weak notes, rules for modulating to a different makam, and the notes and microtones in that makam.

“A makam is often just four or five notes, and not a full eight notes,” Marin says. “But it’s not like a pentatonic scale—it wouldn’t be a 5-note scale spread out over a full octave. To play a full octave, sometimes you’ll have two pentachords on top of each other. It will be one makam starting on C and then another makam starting on G. That will be your one octave of the scale.”

Turkish music is microtonal—that is, it uses notes that land between the keys of a piano. “The octave and fifth are almost universal, because that’s based on a mathematical concept,” Marin adds. “But the second, third, sixth, and seventh—those could be altered, or normal, or close to the tempered [scale]. Sometimes you’ll have a makam that is almost identical to the minor scale. Others are like the minor scale, but the second is lowered—not a flat second, but a microtonally lowered second. Turkish music is very microtonal. For example, my saz has 17 frets in the octave instead of 12.”

As Jasper Verhulst notes, Turkish musicians sometimes play over a drone—although, unlike in Indian music, drones are not a central feature of Turkish music. “A makam is not like a raga,” Marin says. “You don’t have a drone, because makams modulate a lot. In Indian music you have a drone, but in makam-based music, technically, there’s never a drone. If there is a drone, it is played on an instrument that can change pitch so they will be able to modulate with it.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.