Since the advent of language, all things have needed to be called something—especially rock bands. For the latest crew to break out of the psych-rock hotbed of Perth, Australia, a truly absurd moniker was chosen: Psychedelic Porn Crumpets. What does it mean? We have no idea and neither do the fellas in the band. However, like their music, it’s undeniably memorable. Hailing from the same pub and club scene that spawned psych-pop superstars Tame Impala and cult favorites Pond, the Crumpets’ brand of psychedelic rock is decidedly more over-the-top than the fare their compatriots put out. The Crumpets make brash, exuberant music that takes the intrigue and textures of classic psych and injects it with an unhinged, restless energy that feels like peaking on LSD while riding a rollercoaster.

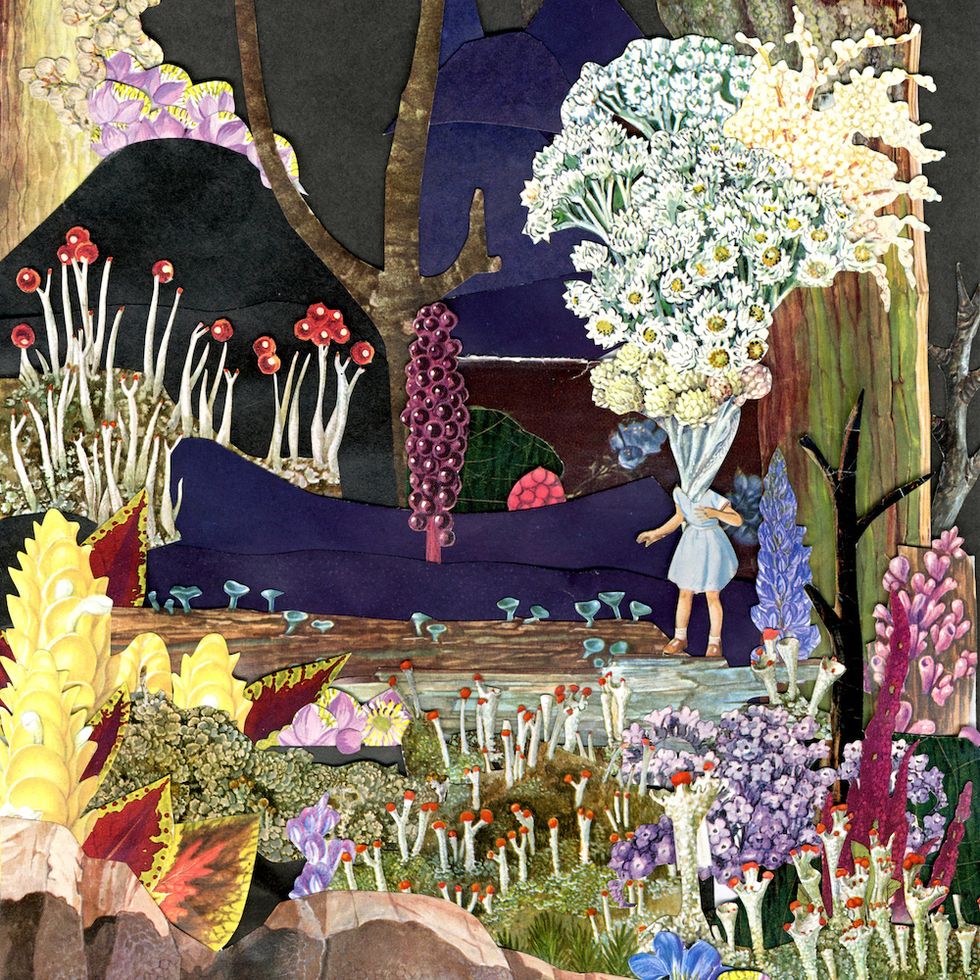

At the core of the Crumpets’ sonic universe is an unabashed love of cartoonishly large and colorful guitars. With their third LP, And Now for the Whatchamacallit, Psychedelic Porn Crumpets have created a loose concept album which applies the aesthetic of a 1930s carnival to the turbulent circus that is touring life for a young band. Tracked chiefly in frontman/principal songwriter/guitarist Jack McEwan’s bedroom studio (with some overdubs done at Perth’s Tone City Studios), And Now for the Whatchamacallit is indeed a guitar carnival that revels in dazzling multi-layered harmonies, chunky, fuzz-laden riffing, and delicate ambient passages that’ve been tweaked, warped, or pitch-shifted in interesting ways. Finished with a dash of ’70s glam pomp and a hearty dose of indie-pop melody, the albumticks a lot of hallowed guitar-rock boxes while forging unique territory.

Beyond being a compelling listen, the Crumpets’ latest release is a fine example of how good a guitar-focused album can be without access to expensive gear, or much reliance on tube amps or even high-end modeling rigs. The Crumpets’ musical identity is a byproduct of Perth’s isolation, where bands are decidedly less overwhelmed by an influx of outside art and additionally forced to use whatever tools they have at their disposal in a place where American-made and/or vintage gear is difficult to come by.

A big fan of the “work with what you’ve got” philosophy,McEwan tracked almost all of his guitar parts in Ableton through DI and employed clever production techniques (like eschewing amp sims altogether for an extremely hot compressor) to get his guitar sounds, which are rarely sterile, despite often sounding like anything but a guitar. While McEwan’s guitars live almost exclusively in the digital realm, lead guitarist Luke Parish is a fan of vintage gear and has hunted down and imported some gems, including a ’60s Sears Silvertone amp and a ’68 Fender Deluxe Reverb, which he used to add organic warmth to McEwan’s digital guitar pastiche. The pair complement each other exceptionally well as guitarists despite having vastly different backgrounds as musicians: McEwan is a converted bass player and Parish came up playing in jazz bands and then followed the typical blues-rock heroes of yesteryear.

We spoke by phone with McEwan and Parish as they rode in the back of a tour van, traversing a Welsh highway. The duo discussed the band’s writing process, unique home-recording techniques, the travails of sourcing decent gear in an isolated locale, and what makes Australia such a fertile place for rock ’n’ roll.

The album has a lot of really complex guitar parts. Could you walk us through your typical writing process and how you go about mapping out those parts?

Jack McEwan: A lot of the time they start with a basic guitar part or actually with a bass part, like a pure, basic riff for us to work out from. Then we add guitars on top of that, progress with the layering and add the harmony bits. We really try to get as quirky as possible, almost like how hair metal bands in the ’80s would solo for the sake of it and have harmonized guitar solos going everywhere, which can be sort of horrible listening nowadays, but it adds a quirkiness we really like for our music. It just gives it a bit more of a bang!

Luke, what’s the writing process like on your end?

Luke Parish: It’s sort of the dinner that’s already made and we add a bit of flavor to things. Jack tends to the majority of the writing and we work more on tones and colors, and also we work it all into something that works in the live environment. A lot of the recordings we do in isolation of each other and once it’s brought to the table, we all have input and have our different angles and attacks to change things up. Jack tends to write really intricate parts and it comes down to sifting through all of those bits and figuring out which ones stand out and where we can add room to breathe between the guitars or make the drums sound more organic and flow. I see myself more as a producer of the record than a writer and take on the role of bringing out the best in the songwriting that’s been done. We occasionally bring our own stuff to the table.

Tidbit: On the Psychedelic Porn Crumpets’ third LP, And Now for the Whatchamacallit, principle songwriter Jack McEwan tracked most of the guitar parts in Ableton through DI, while lead guitarist Luke Parish added flavor with 1960s gear, including a Fender Mustang and Silvertone 1484 Twin Twelve.

There are tons of harmonized guitar leads on the album, but they rarely distract from the song itself. “Social Candy” is a great example. What’s the trick to that?

McEwan: If you place them right, they give the song a bit of a kick and you really have to make sure they’re adding to the root idea. You can triple track something with harmonies and as long as it’s tracing the main idea, it seems to work for us.

Parish: The guitar-monies have become a very strong flavor in our music and that has a lot to do with how good Jack is at just sorting them out slowly. It comes back to us being fans of the Allman Brothers. There are some harmonies that clash in a way that makes you slightly uncomfortable, but it’s because you have to have sour to better recognize the sweet. We like surrounding ugly parts with nicer-sounding melodies and it doesn’t freak you out too much.

Do the vocal melodies come before or after the guitar melodies? For example, I really like the way the vocal intertwines and traces with the guitar on “Keen for Kick Ons?”

McEwan: We record everything pretty much at home, so all the music comes first. Very rarely is there a lyrical idea going in. I’ll sometimes have a vocal melody that I’ll hum and that’s definitely in mind when we’re recording, and I’ll leave specific gaps in the song to place vocals. I’m of two minds where I feel like we could be an instrumental band, and I think it’d be cool—but you’d shrink your fanbase because some people love instrumentals and some people really hate ’em. I’m personally right in the middle, which is why a lot of our songs have these kind of random verses that just appear out of nowhere instead of a traditional structure. On this record, we tried to work on song structures and keeping things shorter to make something that’s really interesting in 3 minutes, rather than some long escapade that stretches on.

You’re both very athletic players. Does one of you bring in more of the guitar flare than the other?

McEwan: We write it into our own respective songs, so it’s sort of baked-in to our own songs. We jammed a lot as a band when we first started and our early stuff was very much constructed as a band, but because we record at home now, we tend to get carried away writing songs and sometimes finish them as individuals. When we’re recording, we don’t really have the band in mind, exactly. It’s more about what’s best for the song and what sounds good; never about whether or not we can play it live.

Psychedelic Porn Crumpets’ lead guitarist Luke Parish is currently playing a new Fender Tele with a humbucker at live shows, but his favorite guitar is a 1969 competition-stripe Mustang that he now relegates to studio use only. Photo by William Johnstone

How do you guys balance each other as players?

McEwan: Luke taught me everything I know about amps and pedals. Before we started this band, I was using a Line 6 amp and he turned me onto valve amps when I had no idea. As players, instinctively I always go lower, as a former bass player, and he goes higher as a proper lead guitarist. It just works perfectly for our music. When we jam on riffs, we instinctively know what the other is going to do and it just works really well.

Parish: We naturally took two very different directions for our tones, so live we’re not competing for the same sonic space. We have our own frequency ranges that work well with each other. Jack goes for that dirtier Vox AC30 thing with a bit more crunch and I like a cleaner sound like I get from my Deluxe Reverb, so you end up with slightly different tones that work against each other well. As far as playing, we’ve always played really tight together, ever since the beginning. We’ve always been able to hang with each other’s playing and there really is a lot of intuition. We were never waiting on the other to learn parts or playing catch up. We just lock in quickly and it’s always been that way.

Luke, can you give me an example of where we hear your work the loudest on the new album?

Parish: Definitely in the more ambient guitar tones and also the stuff that brings out the grittier, heavier side. I lean towards real amps and pedals and Jack tends to work with DI’d guitars, though I DI my guitar often. I feel like I often add the glue between those DI guitars, as they can lack either the smoothness or the rawness of a real amp … that organic element.

Which guitarists have influenced you guys?

McEwan: The biggest one these days is Ruban Nielson from Unknown Mortal Orchestra. When I was just starting out, loads of Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin— the greats—but as I got older, stuff like Foals really changed my landscape by playing the guitar in a way that I hadn’t heard before that doesn’t always sound like a guitar. When you’re 25 and you think you’ve heard everything and something refreshing like Unknown Mortal Orchestra hits you and blows your mind, it’s a big deal. Stuff like, “Why does he only play two notes at a time?” or “How does he make it sound so full through compressors and recording techniques?” So now when I pick up a guitar, I ask myself if it really needs so many notes or what’s the biggest effect I can get with the most minimal approach, which took a lot after years of listening to Tool and Mars Volta. I needed to learn more about space and negative space, and Ruban’s playing did that for me.

Parish: I came from playing in old jazz big bands, and then blues music and all of those old blues legends. I really like guitarists like Django Reinhardt, and then for rock and blues, Jimmy Page and the real ’70s rock legends, and then I got into Radiohead and Blur, and that really changed my approach. Graham Coxon showed me how experimental you can get with guitar and all of these new effects pedals being released now. And with companies stepping up their game, my inner nerd has definitely come out through the world of technology and effects. Obviously you’ve always got to be focused on your playing first, but guys like Jonny Greenwood are prime examples of good players that tastefully use the tech available to make something new.

I really dig the fuzz sounds on the album—particularly the wooly tones on “Keen for Kick Ons?” What did you use to cop those sounds and did you use any unique studio techniques to track fuzz?

McEwan: Live, I use a Way Huge Swollen Pickle and a Boss Blues Driver, and I just crank the amp until it’s good and warm and punch it with those. For the album, it’s kind of a cheat, but a lot of that is DI’d into Guitar Rig. I have a go-to technique where I take off all the amp sims and use the compressor plug-in straight up and really crank it until it sounds like your speakers are about to explode. I can’t afford a lot of gear, so a big part of our records involve having to learn tricks, like with direct recording. There are so many incredible plug-ins these days, it’s so much more accessible.

I know it’s very difficult and very expensive to get quality guitar gear and especially vintage stuff in Australia.

McEwan: There is nothing really here. When we go to England or America and we go to music shops, sometimes it’s just to have a look at what these things really are! It’s like, “Oh my God! You can actually buy this?!” In Australia, it’s pretty much brand-new stuff or you find off-kilter gems, but it’s tough.

Guitars

1969 Fender Mustang

1970s Greco Speedway

Fender Telecaster

Amps

1968 Fender Deluxe Reverb

1960s Silvertone 1484 Twin Twelve with 2x12 cab (Jensen speakers)

Effects

Strymon BigSky

Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Memory Boy

Analog Man Prince of Tone

Xotic EP Booster

Boss volume pedal

Unbranded tremolo pedal

Fuzzhugger Algal Bloom

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Slinky strings (.010–.042)

Dunlop Jazz III picks

Parish: You really just have to be ready to pay for shipping. I found my Silvertone on eBay maybe 12 years ago and it was only $500 or something, but I paid the same amount to get it shipped over as I paid for the amp and it still needed its electronics gone through. But if you really want the gear, you just have to do it and it’s all part of the deal. Try to find a bargain and once it’s over here and you’ve had it fixed up, the value is going to be much higher because it’s all so sought after because the gear just isn’t floating around the way it is in America and England and whatnot. I haven’t bought that much stuff because once I had those amps and my ’60s Fender Mustang, I felt like I had what I needed.

Jack, what made you favor Fender Jazzmasters?

McEwan: I’ve been playing Jazzmasters since the beginning of this band, and before that I was a bass player. It was funny to transition from that, so I use really heavy strings on the Jazzmaster, but I keep it in standard tuning. I like how well it holds its tuning and the tone it gets set up like that. It feels a little more like a bass. That’s probably why the stuff I write is a bit more riffy than it is chord-based. I like a Jazzmaster through anything that’s raw sounding, like a Vox AC30. That was the first amp I got, and it was broken when I got it, but I had no idea. I was just like, “This sounds amazing!” because it was so distorted and cool sounding. I didn’t like it anymore after I got it serviced, but luckily I managed to record some music with it while it was dying. Nowadays, I use a Fender Hot Rod DeVille live because it’s got its own warm drive sound built-in. I love the idea of just working with what you’ve got. The way the band has been writing lately honestly may have had something to do with heavy psych-rock sounding so good through that broken amp. It accentuates that sound, and the gear can tailor your sound sometimes.

Luke, tell me about your Mustang.

Parish: It’s a 1969 competition-stripe model and the neck on it is amazing. It’s a nice, nice guitar, and I don’t take it anywhere because I’m too paranoid something will happen to it. I tracked most of the record with it. I also have a guitar called a Greco Speedway, which is this ’70s walnut solidbody with a through-body neck, and that guitar is really good. Live, I’ve switched back to Fenders and I’m using a newer Tele with a humbucker in it.

What’s the trick to getting those big guitar sounds in a home-recording situation?

McEwan: Almost all of it was DI on my end. I live with housemates and the minute you turn the amp on, they kind of get upset, so I got used to recording with a really minimal and quiet setup. I started with a $10 microphone and some iPhone earbuds, but I’ve worked my way up to some proper monitors. Effects were all in the box, but you can do quite a few things with that! I started tweaking things through transposing, detuning, and pitching the guitars in weird ways and then adding reverbs to make sounds I wanted to hear. We use Ableton and between its pitch shifters, bit crushers, and delays, I can make a guitar sound like almost anything. I started getting really into messing around with post-production to see what I can get out of a guitar. Things like reversing guitars and playing the reverse line backwards made a cool thing, and when you’re home and recording off-the-clock, experimenting is a lot easier and more fun.

“I’ve been playing Jazzmasters since the beginning of this band, and before that I was a bass player,” says Jack McEwan. He uses heavy strings on his Jazzmaster to get a tone that feels more like a bass. Photo by Alice Sutton

Luke, as the band’s tube-amp guy, what amps did you record the album with?

Parish: I’ve got a 1964 Sears Silvertone piggyback amp that I tracked a lot of this album with. It’s got the same tubes in it from 1964 and it’s such a nice amp with a great bluesy, gritty tone. Anything grittier is that amp, and then for the delayed, airy-sounding guitars, I used a 1968 Fender Deluxe Reverb, which does that clean, bigger headroom thing so well. That Silvertone is really my baby, though. I love that thing!

“Fields, Woods, Time” and “Native Tongue” as a pair are great examples of that heavily tweaked post-production technique. Can you tell me what we’re actually hearing in some of those guitar parts—particularly those bits that sound like insects buzzing around?

McEwan: Both of those songs are almost all guitar, aside from the string quartet and a little bit of synth in the sub frequencies at the end. Everything there started off as one little guitar piece that I had and I just kept layering and layering over it until it sounded ridiculous, and rather than taking the ridiculous sounding bits out, I left them in and took away the clean parts. When all of those overdubs were left without the original concept, the whole thing changed into what you hear, which includes a lot of the things that Luke mapped out over it. That happened to a lot of these songs, actually. Also, I had a sitar and all of the strings had snapped off but two, so I was super limited, but I really wanted that sound on a track. So I figured out what key those strings were in and we did a guitar thing around that. I made a drone out of that sitar sound and put it on a loop with a huge amount of reverb and delay, and the sitar’s pickup was dying and crackling when I was using it, so the sound of the pickup dying and crackling are actually those weird bird-like clicks you hear on that track.

The riff that opens “When in Rome” is really killer.

McEwan: Yeah! With “When in Rome,” I remember I was listening to Dopesmoker by Sleep on repeat. As soon as I stop listening to something after that kind of repeated absorption, I tend to have those ideas infiltrate my playing and they’ll come out when I record ideas. I’ll usually chop things up or move them around structurally, but that song just came out the way it is on the album. It just rolled really easily with that vocal pattern. We really worked hard to keep the intensity and keep it heavy, but give it clarity and dynamics so it’s not just all headbanging—though we almost made it as intense and heavy as possible.

How do you approach getting those songs together live, considering how many parts are involved and how much chopping gets done in Ableton?

McEwan: That’s the million-dollar question, isn’t it? Once you create something in a bedroom and then take it back to a band, you sort of feel like you’re bastardizing your own music. It needs to take on its own thing live, and songs like “Hymn for a Droid,” “Keen for Kick Ons?” and “Bill’s Mandolin” are aimed at a rock band, but songs like “Dezi’s Adventure,” “Native Tongue,” and “Digital Hunger” require an eight-piece band to emulate the quirky bits of record live. We let the songs take on their own life live and that isn’t necessarily exactly what’s on the album. I love having a good tone or hearing a huge guitar-amp sound like on Tame Impala records. And once we have that sort of budget or learn those recording techniques, I’d love to chuck that in a record, but we’re really more idea-focused than tone-focused because of our recording restrictions.

Parish: For those DI parts, I use a Strymon BigSky live as they’re quite versatile for reverbs and sparkly stuff. Some of the effects on the record you realize pretty quickly there’s just no way to cop live, and I’ve always stuck to analog pedals for the most part, so it’s been tricky trying to work some of the more complicated digital stuff in. My most used effect live is an Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Memory Boy delay. I bought that pedal, and the track “Entropy” on the first Porn Crumpets record was born out of a specific function from that pedal, where you hold down one of the buttons and it cycles through the pedal’s rhythmic settings.

Guitars

Fender American Special Jazzmaster

Amps

Fender Hot Rod DeVille

Vox AC30

Effects

Way Huge Swollen Pickle

Boss BD-2 Blues Driver

Boss TE-2 Tera Echo

Way Huge Echo-Puss

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Power Slinky strings (.011–.048)

Dunlop .60 mm picks

Jack, you mention Tame Impala and you guys are from the same scene in Perth. Between Tame Impala, Pond, and King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard, Australia seems to be a really fertile place for guitar rock these days.

McEwan: I think basically because it goes really well with beers! You can just go to the pub and there’ll be bands on and it just works. And the weather plays a role, too. Australia has 300 days a year of sunshine, and you don’t really want to be inside in a club, but outside in a garden with a band cranking! People socialize more around that and if you go to see a band that’s really good and catchy, that’s the most inspirational thing you can witness and it builds a scene. When we started off in Perth, I’d go to house parties and there would be one band playing inside, another one in the garden, a skate ramp with people riding, and you felt like you were part of the music scene instantly, even if you didn’t play an instrument. It was very welcoming. Those bands that play in the gardens and lounges of your friend’s weird house are also playing pubs and clubs and it’s very inspiring. You’ve got that kind of scene throughout Australia, Melbourne, and Sydney—bands all seem to have similar stories. I think it’s got a culture built around it in the same way the California scene does, which I think is why a lot of the California psych bands like Frankie & the Witch Fingers, Ty Segall, Wand, all have a similar sound. I think that’s the American sibling scene to the Australian bands like King Gizzard and that group of bands.

Parish: I remember reading an article with Nick Allbrook from Pond and he was talking about Perth’s isolation from the rest of the world makes us a bit ignorant to what’s out there, or at least not as overwhelmed by everything. Say you’re a painter and you grew up in France. You’ve got thousands of years of famous painters and works and it’s quite daunting to come out in the art world because of what’s already been and what’s there. We don’t get a lot of artists through Perth. It tends to get left off of a lot of tours because it’s so far away and expensive to get to, even within Australia. So that isolation aspect means people feel like everything they’re doing is either really original and creative, or they’re at least not so daunted by what else is out there already. You’re in a bubble and everyone’s really excited and energetic about making music. You’re not confronted by feelings of oversaturation or being inundated with bands like someone trying to do a psych band in L.A. or something.

Watch the Psychedelic Porn Crumpets recreate their complex songs onstage during a full set earlier this year in Lille, France.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)