If Ulrich “Uli” Teuffel had lived during the Middle Ages—and if guitar nuts were as passionate about their opinions and traditions then as they are now—chances are, the German builder would’ve been burned at the stake. Heck, even today, if you happen upon an online discussion of Teuffel’s guitars, there’s a good chance you’ll witness a cyber-lynching of the man and/or his work. Chief amongst the cries of heresy and blasphemy is the charge that Teuffel doesn’t even play guitar and is merely concerned with unique aesthetics. Of course, the same could be said of Leo Fender and Ned Steinberger, two of history’s most innovative guitar designers.

But the fact is, Teuffel does play guitar. And as you can see in the photos of his first guitars from the 1980s, he revered both the Les Paul and the Strat—so much so that he created gorgeous renditions that are remarkably similar to the iconic designs. He also built “super strat”-style electrics, basses, and an acoustic guitar based on a Steve Klein flattop.

“I still look back on that early period with fondness,” Teuffel says, “it was filled with an intense desire to learn how to build a perfect guitar … I was working toward critical evaluation and getting my guitars accepted as equivalent to or better than those in the shops.”

Tueffel's Niwa model.

Tueffel's Niwa model.After Teuffel achieved that level of expertise—aided no doubt by his time as a metalworking apprentice at Mercedes- Benz—his inner innovator wouldn’t sit still, wouldn’t be content just trying to fine-tune other minds’ visions. He enrolled in industrial design school and found inspiration in the work of an instructor by the name of Hartmut Esslinger— who happened to be the designer of the original Apple Macintosh computer. Soon thereafter, Teuffel came up with his futuristic Birdfish model, a modular homage to Leo Fender that features interchangeable wood “tonebars,” sliding pickups that can be swapped out in seconds, and a twopiece aluminum body.

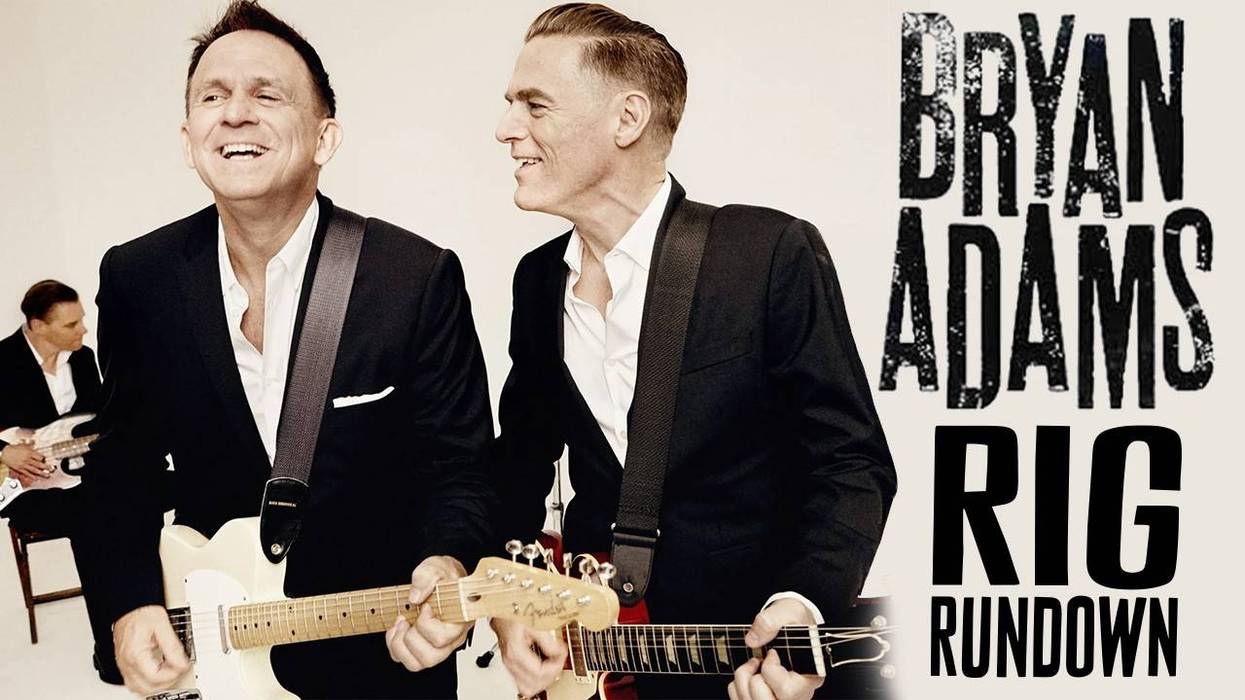

Ulrich Teuffel

and his homemade corduroy trousers in his shop in Neu-Ulm, Germany.

Ulrich Teuffel

and his homemade corduroy trousers in his shop in Neu-Ulm, Germany.“I see my work as an oeuvre to be completed once. So there are periods to go through. I’ve left the common guitar behind me at this point, and I know I will never turn back. All of my former models are history—I even threw away all the leftover bodies and necks.”

As proved by the Birdfish and the Bavarian luthier’s two other main designs—the Tesla and the Niwa—Teuffel isn’t afraid to mess with tradition. Every year, he builds 25 guitars ranging in price from $7000-$15,000 in his one-man shop, and he designs and machines everything from the bodies to the pickups and even tiny stainless-steel screws for his proprietary locking nut. The man is a relentless and incorrigible tinkerer. When questioned about why he uses a standard Tune-o-matic bridge on instruments that flout every other 6-string tradition, you can practically hear the gears (precision-machined, of course) turning in his head. But what do you expect from a guy who custom-ordered high-end corduroy and taught himself to make pants when he couldn’t find suitable trousers at the store?

How would you say your apprenticeship at Mercedes-Benz

affected your design philosophies as a luthier?

My design approach has actually been guided more by my design

teacher at the university, Hartmut Esslinger, who is the designer

of the Apple Macintosh. The apprenticeship at the car company

affected my execution work and handcrafting skills—I learned

to work with metal as if it was wood. Before that, I used to work

with wood only.

Other than a balalaika that he constructed out of an old desk when he

was 13 years old, this Steve Klein-inspired acoustic from 1985 was the

first instrument Teuffel ever built.

Other than a balalaika that he constructed out of an old desk when he

was 13 years old, this Steve Klein-inspired acoustic from 1985 was the

first instrument Teuffel ever built. You were later inspired by Steve Klein’s designs. What drew you

to them?

I discovered his guitars in Donald Brosnac’s book The Steel String

Guitar: Its Construction, Origin, and Design. I was thrilled by the

look and the layout of his instruments. In Germany, none of his

guitars were available, so I decided to build my first guitar after

Steve’s design.

Was that first guitar your acoustic?

Yes. In the German issue of Brosnac’s book, there were photos of

three of Steve Klein’s guitars. When I saw the picture, I decided to

build a “cover” version of those guitars.

Who were your musical heroes when you first got into guitar?

And did they affect the path you took as a luthier?

When I started to build electrics in the late ’80s, I was captivated

by the Mark Knopfler tone—that bridge-and-middle-pickup

sound—and I developed a way to achieve this tone with two humbuckers

and a single-coil, too. At the end, though, I realized you

need a Strat with three single-coils to get that tone 100 percent.

From Townes Van Zandt and Mark Ribot, I learned about the

pure tone of a simple instrument. Finally, Johnny Marr from the

Smiths inspired me to build a 12-string electric. Eddie Van Halen

gave me an impression of how a Strat with a humbucker can

challenge a Les Paul. I really like that tone. David Torn appeared

on my radar in the ’90s, and he is one of those rare free spirits.

“I made 10 acoustic guitars while I

worked as a trainee at Daimler-Benz. This is my personal guitar, so it has

a wide neck for fingerpicking. It has survived some campfires and has

many dings from that era.”

“I made 10 acoustic guitars while I

worked as a trainee at Daimler-Benz. This is my personal guitar, so it has

a wide neck for fingerpicking. It has survived some campfires and has

many dings from that era.”How did Torn affect your building approach?

What Means Solid, Traveller? was the first Torn record I bought. At

that time, I had already designed the Birdfish, but David had an

influence when I designed the Tesla. One year after I introduced

the Tesla, he called me and told me he liked it and asked me to

build a custom version with a [Steinberger] TransTrem and another

control for his looper.

What do you remember most about your earliest guitars—the

traditional designs?

I still look back on that early period with fondness—it was filled

with an intense desire to learn how to build a perfect guitar. It was

an experimental time—not in the manner of pushing the envelope,

but in achieving a professional building level. I was working toward

critical evaluation and getting my guitars accepted as equivalent to

or better than those in the shops. When I achieved that, my attention

switched to guitar design. That was when I decided to study

industrial design.

Why did you feel that studying industrial design was the next

logical step in taking things to the next level?

I worked really locally, and therefore I couldn’t get a lot of first-hand

feedback from major players. On the other hand, I always came up

with unconventional ideas for my early guitars, but most of those

ideas didn’t resonate with the demands of my local clients—who were

mostly playing in Top 40 bands. So I realized I had to go to a broader

public. Before taking that step, I wanted to have a kind of sabbatical

from guitars and get a profound education in how to bring ideas and

concepts into the stadium of production at the same time.

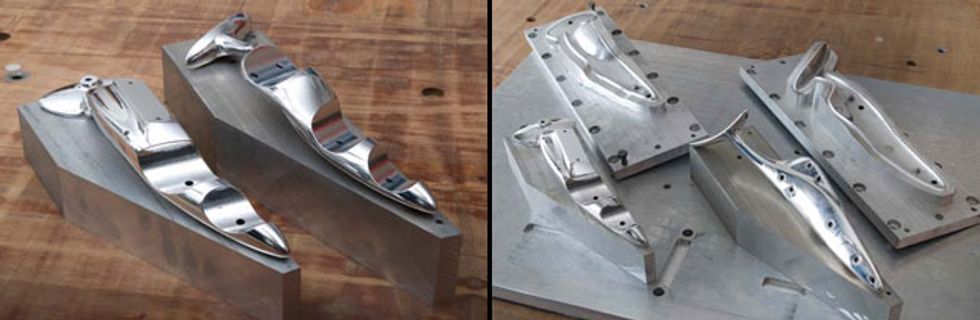

Above left: A finished bird and fish set. Above right: Vises for creating the aluminum “bird” (right) and “fish” (left) portions of the Birdfish’s body anchors.

Above left: A finished bird and fish set. Above right: Vises for creating the aluminum “bird” (right) and “fish” (left) portions of the Birdfish’s body anchors.Although you’ve made a mark with totally unique designs, do you

ever miss making more straight-ahead instruments—and would

you ever go back? And what about basses—will you ever make any?

I see my work as an oeuvre to be completed once. So there are periods

to go through. I’ve left the common guitar behind me at this

point, and I know I will never turn back. All of my former models

are history—I even threw away all the leftover bodies and necks of

my Dr. Mabuse series from the ’80s when I first put my workshop

in order. But there are some things I miss from that period. For

instance, polishing the varnish when you’re doing a glossy finish.

Each of my current models is painted in a soft-feeling matte finish.

I did this to create a design identity, but in the future I will probably

work with glossy finishes again.

Teuffel built this Strat-style guitar in 1989, and it

features a swamp-ash body, a bird’s-eye maple neck,

Häussel pickups, and a heavy-duty Schaller Sure Claw

(inset). “I bought back a few of my older guitars from

clients, because I wanted to have them for my private

collection,” Teuffel says, “and I knew I would never

find the time to build duplicates after 1995.”

Teuffel built this Strat-style guitar in 1989, and it

features a swamp-ash body, a bird’s-eye maple neck,

Häussel pickups, and a heavy-duty Schaller Sure Claw

(inset). “I bought back a few of my older guitars from

clients, because I wanted to have them for my private

collection,” Teuffel says, “and I knew I would never

find the time to build duplicates after 1995.”For the same reason—to create an identity—I stopped making basses when I started with the Birdfish series. I was afraid that basses would dilute my work. In my eyes, there is no way to succeed in building guitars and basses at the same time unless you’re Leo Fender or one of the companies building generic guitars or modernized Fender-based instruments, like all the major companies now. Honestly, do you really appreciate a PRS bass or an Alembic guitar? I built about 30 basses in the late ’80s and early ’90s, but I haven’t picked it up since then.

Teuffel came up with his

fi rst from-scratch guitar design,

Dr. Mabuse, in 1988. He made

20, and they featured set mahogany necks

and bodies, sometimes with a flamed maple cap.

They had three pickups, usually with a humbucker

in the neck and bridge positions. “You couldn’t get

Strat-type switches with more than two switching

layers then, so I used rotary switches with six layers.

The scheme was 1) bridge, 2) split bridge and middle,

3) bridge + neck, 4) middle + neck, 5) neck. Positions

1,3, and 5 were passive, while positions 2 and 4 went

through an onboard preamp that boosted the signal

and accentuated bass and upper mids.”

Teuffel came up with his

fi rst from-scratch guitar design,

Dr. Mabuse, in 1988. He made

20, and they featured set mahogany necks

and bodies, sometimes with a flamed maple cap.

They had three pickups, usually with a humbucker

in the neck and bridge positions. “You couldn’t get

Strat-type switches with more than two switching

layers then, so I used rotary switches with six layers.

The scheme was 1) bridge, 2) split bridge and middle,

3) bridge + neck, 4) middle + neck, 5) neck. Positions

1,3, and 5 were passive, while positions 2 and 4 went

through an onboard preamp that boosted the signal

and accentuated bass and upper mids.”On your website you talk about that transition away from

building traditional instruments. “I was dissatisfied with my

guitar work … I had been looking for a wider challenge, which

I couldn’t find in the realm of traditional guitar building …

[from] my study, I learned to look at my guitar work from a distance.”

What did you mean by that?

If you are concerned with your everyday work, you won’t see the

whole picture. I interrupted my guitar-building work while I studied

design and became concerned with a different approach to

creating things. The common way is to imitate existing things with

some modifications and maybe some improvements. The other way

is to go back where it really starts and to put things together in a

new way. This is what I did after the study.

The front and back of an alder Niwa body.

Note the smooth, fi nely cut cavities and incredible attention

to detail in everything from the fl owing body lines to the

placement of hardware routes.

The front and back of an alder Niwa body.

Note the smooth, fi nely cut cavities and incredible attention

to detail in everything from the fl owing body lines to the

placement of hardware routes.Can you briefly describe the genesis of each of your three main

guitar designs?

The Birdfish is a guitar that follows Leo Fender’s principle of

designing a disassemble-able guitar that enables you to interchange

body timbers and slide-able pickups. The Tesla [Classic] was

intended to emphasize the use of guitar defects [hum, microphonic

feedback, and a killswitch] that are isolated on the three momentary

buttons. The Niwa was intended to be an ergonomic design

with more traditional headstock construction.

Why do you work alone, as opposed to having people who specialize

in, say electronics or metalwork?

If you are really interested in how things work, you will become

better than any specialist. Just ask Ken Parker. I can’t imagine getting

more satisfaction than I do when I’m learning new techniques

and skills. It puts me in the position of being able to paint the

All your guitars are dreams to play. The action is low and there

doesn’t seem to be a sharp corner to annoy one’s hands anywhere—

from the nut to the bridge. However, the Tesla guitar

can be a bit of an adjustment: Although its scale length is 25.6",

the bridge is so close to the butt-end of the guitar that it can

feel like you’re missing a couple of inches of guitar neck when

you’re reaching for open-position chords. In addition, fretting

higher on the neck can feel awkward for players who like to feel

their thumb wrap around the other side of the neck. What was

the impetus for these pretty radical ergonomics?

The neck access on the higher frets is much different from a normal

neck—you can’t wrap your thumb around—but the tonal benefits

from this supported-neck construction made me decide to go for

this uncompromising solution. I don’t see my guitars as examples

of how guitars should be. Each year, we see maybe six million conventional

electric guitars for traditionalists put on the market—plus

my 25 unconventional guitars for unconventionalists.

A collection of Niwa necks. At left are a pau ferro fretboard and

Teuffel’s proprietary stainless-steel truss rod—which weighs only 1.7 oz.

A collection of Niwa necks. At left are a pau ferro fretboard and

Teuffel’s proprietary stainless-steel truss rod—which weighs only 1.7 oz.Considering your engineering background and how radical your

designs are—from the shapes to the finish to the pickups and

their housings to things like the Niwa’s recessed tuners—it’s

somewhat surprising that you mostly use stock bridges and tuners.

Why?

When I started with the Birdfish in 1995, I used the Tune-o-matic

bridge as a ready-made part because I wasn’t able to produce my

own bridge at that time. Later, I liked the fact that this bridge kind

of connects my guitar with the traditional heritage. The Tesla first

had an ABM bridge, but I found that the Tune-o-matic sounded

better. It’s interesting that you mention this, though—maybe I

should design my own bridge with the same tonal character. Do

you think the Tune-o-matic undervalues the spirit of my guitars?

No, I wouldn’t say it undervalues it at all. I was just curious if

you’d thought of designing your own—especially since you’ve

designed and made much smaller components such as screws in

your own shop. That said, I would love to see what you’d come

up with if you did design your own bridge.

Thank you! I’m putting that idea in a corner of my brain where I

can retrieve it anytime.

Handpolished stainless-steel neck screws and matching threaded

inserts. Grooves for the inserts are precision cut into the neck cavity.

Handpolished stainless-steel neck screws and matching threaded

inserts. Grooves for the inserts are precision cut into the neck cavity.The Tesla and Niwa have very wide, flat knobs. What’s the

design philosophy behind those?

I use the Tesla volume pot for swell sounds in the opposite direction.

So the swell direction of movement goes down with the stroke

of the playing hand. The larger diameter makes the swell sound

more scalable. The Niwa selector knob continues the design of the

volume and tone knob.

Your pickups tend to have a hot and somewhat hi-fi sound to

them. What sounds were you going for when you designed them?

Most of the players who write reviews of my guitars describe their

tone as quite vintage, but I know it is always difficult to get the

same opinion on the same guitars. My sound vision is more a

Fender tone than a Gibson tone—quick attack with a warm pop.

In order to get this—and keeping in my mind that my guitar bodies

are mostly from red alder—I design my pickups in a way that

they achieve the Strat-like tone but with more volume.

My major pickup type for the Tesla and Niwa is a split coil that has one bobbin with three magnets for the treble strings, and one bobbin with three magnets for the bass strings—similar to the Precision bass pickup. No pickup can exactly paint the sound of a vintage single-coil except a vintage single-coil, but this is not my ambition. I evolved the split-coil design for the particular tonal needs of my guitars. The Tesla has to have a Hendrix-like neck sound, but louder and without hum—and sharper, too, because it’s a noise-cancelling single-coil. The split coil is perfect for this demand. The Niwa’s pickups use another type of split coil—different magnets, different wires, and a different number of windings. The guitar should sound like a fat, full Strat, with a hotter, Teletype bridge sound. The Tesla bridge pickup is a humbucker made in a more standard way. Since 2009, I’ve used the same configuration I made for [Metallica’s] Kirk Hammet.

Of course, I also make custom pickups for my clients. The Birdfish has three different humbuckers—from a very hot, PAF-like version to a P-90-like version, and two real single-coils that have more of a vintage tone. I haven’t built active pickups or circuits since 1995.

Teuffel made approximately 20 John F. Kennedy

series basses, most of which were

maple neck-through designs with rosewood

or ebony fretboards, Bartolini pickups, and

a passive 2-band or parametric 3-band EQ.

Three were 36"-scale 5-strings like this one

from 1991, but most were 34"-scale 4-strings.

Teuffel made approximately 20 John F. Kennedy

series basses, most of which were

maple neck-through designs with rosewood

or ebony fretboards, Bartolini pickups, and

a passive 2-band or parametric 3-band EQ.

Three were 36"-scale 5-strings like this one

from 1991, but most were 34"-scale 4-strings.Watch Editor in Chief Shawn Hammond demonstrate the Tesla, Niwa, and Birdfish:

Most pickup aficionados are familiar with alnico 5 and alnico 3

magnets, but you use both alnico 5 and alnico 8 in the Tesla and

Niwa pickups. Why?

I use the alnico 8 magnets for the inner magnets of the split-coil

pickups, where the north pole and the south pole are facing the D

and G strings. Alnico 8 has a stronger field power, and this compensates

for the partial elimination of the field. When I work with

alnico 8, I don’t load the magnets up to the full saturation. I usually

go up to 85 percent of the magnetic saturation. To do that, I use an

adjustable impulse magnetizer. After that, I measure the magnetic

field strength of each magnet. This is very important, in my opinion,

because it plays a major role in the harmonics of the tone.

I also have other magnet types—alnico 2, 3, 5, 6, and 8—but I only use alnico 2 and 3 for custom pickups. My job is not to rebuild classic vintage guitars. I believe the fact that everyone is looking for vintage pickups isn’t based on the fact that they are the best-sounding pickups—people are looking for very early pickups that were designed before instruments and players evolved [to where they are today]. But of course, these pickups and guitars were big parts of [some of ] the most important [guitar] recordings. In the ’50s, you had to play a ’50s guitar—there were no ’60s guitars yet. In the meantime, I try to stay away from all the tautological phenomenon of perception and try to find out about and improve what is in the system—from magnets to wire. Because the look of my guitars is so different, I don’t have to copy the look of old pickups. This gives me the freedom to work on my own sound nuances.

In the ’90s, Teuffel built a few modern

Strat-style guitars with set necks, flamed-maple or alder

bodies with a maple top, and open tremolo-spring cavities.

“To me, open trem routing is a business card for good

workmanship,” he says, “but you have to sand, paint, and

polish the cavity, too.”

In the ’90s, Teuffel built a few modern

Strat-style guitars with set necks, flamed-maple or alder

bodies with a maple top, and open tremolo-spring cavities.

“To me, open trem routing is a business card for good

workmanship,” he says, “but you have to sand, paint, and

polish the cavity, too.”The Birdfish is named after two aluminum tone bars that support

the main components. Your website says you used aluminum

because it transfers vibrations without adding tonal coloration.

Is it really possible for a part to have no effect on tone?

I just realized the translator of my website didn’t translate that part

correctly. You are absolutely right. Of course each single element and

material has an influence on the tone—the pick, the string, bridge,

timber, etc. Aluminum transduces the vibrations almost without a

filter influence. When I made the first prototypes, I experimented

with brass, steel, and different sorts of aluminum and hardwood. The

sound of the aluminum joint came extremely close to hardwood.

Since 1995, you’ve overhauled the Birdfish in four stages. What are those stages?

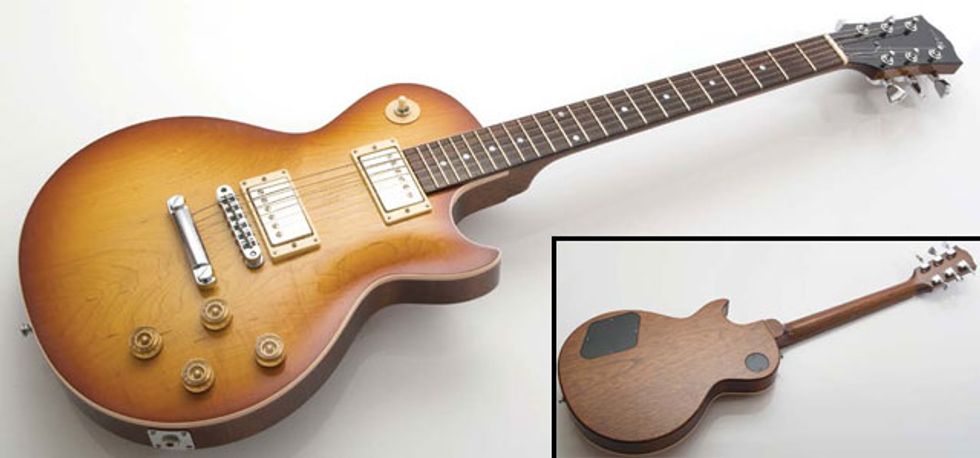

This 1993 single-cut is one of very few

Teuffel-made Les Paul clones. The

cedro body features an alpine maple

top, and the pickups are Häussels.

This 1993 single-cut is one of very few

Teuffel-made Les Paul clones. The

cedro body features an alpine maple

top, and the pickups are Häussels.How do those different aluminum-shaping methods affect the final product?

The fretboard on this version features yin-yang

position markers.

The fretboard on this version features yin-yang

position markers.You even make your own screws sometimes. Why?

The screws for the locking nut are small but rigid. Regular stainless steel

screws aren’t durable enough for that purpose, so I had to use

a stainless-steel alloy that can be hardened. But they have to be custom

made, because you can’t buy screws made of that material.

Do you ever plan to unveil new designs—and, if so, when? Or

do you find yourself spending most of your time building the

existing ones and thinking of ways to improve them?

I am very busy with building the current models, but I am working

on a new model for next year.

What can you tell us about the new model?

The new model is my journey back into guitar history. It will be an

electric guitar, but it will deal with elements from classical guitars

and elements of my own work history. The project name is Antonio,

and it will be finished for the 2012 Montreal Guitar Show.

What do you say to traditionalists and naysayers who think your

designs are inspired more by a desire to be unique and artistic

than to address practical musical needs?

I once had a talk with David Torn exactly about that, and he said

some people say his music isn’t music. Some people say my guitars

are not guitars. And some people visit museums of modern art and

say “This is not art.” I have a deep respect for traditional guitars,

and I have spent many years building them and learning from

them. My newer models are founded on this tradition. But guitar

playing now seems to mean something akin to taking part in a kind

of reenactment—as if you are role-playing the battle of Gettysburg.

You could call this the Stradivarization of the electric guitar. But if

you don’t see yourself as the role-playing type of guitar player, you

might be attracted by the freedom that my guitars will give you—

because they don’t lock you into the scenery of a reenactment.

When assembling pickups, Teuffel first inserts the alnico magnets in a magnetic vice.

He then glues on the bobbin’s bottom plate.

And then removes the assembly from the vise, flips it over, and glues on the top plate.

More glue is then added to reinforce the structure.

The magnets are then insulated with a thin layer of tape.

Pickups being wound onto a bobbin.

Potted Niwa pickups setting in a vacuum chamber.

Teuffel soldering a Niwa humbucker.

Niwa pickups being assembled in their wood covers prior to final shaping.

Niwa pickups (with a subtle leaf motif) after installation.