Hi Jeff

For many years, I’ve been playing hard rock with British master-volume amps (i.e., Marshalls). Lately I’ve fallen in love with the sound of a Marshall 1959SLP. Besides enjoying the slight breakup distortion, I like the amp’s great dynamic range. My picking pressure can make the amp go from a clean, chimey sound with a “hollow” low end that really cuts through to a great mid-rangey, crunchy, distorted sound. I’ve tried to replicate this with master-volume amps like a Marshall JVM or Orange Rockerverb by reducing the gain, but I just can’t get the same dynamic response. Do non-master-volume amps inherently have a better dynamic response? Would class A amps come closer to what I’m looking for?

Len

Hi Len

Nice observation. You’re correct that most amplifiers designed with master-volume controls don’t have the dynamic range and headroom of non-master-volume amps, but it’s more than simply a case of a master-volume control being inserted into the circuit. Here’s my opinion on the subject.

Let’s use your two-channel, four-input model Marshall 1959 as an example. Say you want to run the volume controls on channel 1 and 2 at high levels to achieve a bit of preamp overdrive, but need to play at a less-than-ear-shattering level. (We’ll assume you’ve jumpered channels 1 and 2 together, because that’s where the magic lies in this amp.) If we were to modify this amp and properly install one of several different master-volume circuits, you could lower your volume level with decent results, albeit with a reduction of dynamic range.

This loss of dynamics happens for two reasons: You’re saturating the preamp section, and the master-volume circuit is preventing the full signal from reaching the output stage. If you crank the master volume to 10 and set the volume controls on channel 1 and 2 as you currently do, the amp would sound virtually identical to the way it does now. At this point, you’d realize that the lack of dynamic range is not entirely a result of having a master-volume control in the circuit.

So what’s causing this lack of touch sensitivity and extreme playing enjoyment? The basic answer is “too much stuff!” Most master-volume amps are designed with additional gain stages in the preamp section to achieve a considerable amount of front-end gain and produce a substantial amount of overdrive. This usually means more instances where the signal is amplified, filtered, attenuated, altered, controlled in some way, and then re-amplified and treated all over again. More circuitry means more places for the signal to get lost.

All of this detracts from the signal’s purity and dynamic range. Some of the very early “British”-style master-volume amps (such as the Marshall 2203) are not as guilty of this and can have some pretty decent dynamic range and headroom, but the more current amplifier designs are generally horses of a different color. For me, this is a great argument in favor of “less is more” design. If you want a big, open, responsive, chimey, full-bodied sound, the more basic the circuit, the better the result. As you’ve already found out, your Marshall 1959 is a prime example of this design philosophy.

Regarding your question about a class A amplifier possibly coming closer to what you’re looking for, first let me say I believe the only true class A amplifier is one with a single-ended output stage, such as a Fender Champ. That said, while most output stages that builders describe as class A can be responsive and sound pretty dynamic, the amp’s tone is also going to depend on the design of its front end. Too much stuff in the signal path could equal too little tone.

A quick clarification: One of the sentences in my last column regarding speaker impedances read, “A higher number of turns in the 16-ohm coil may slightly increase the response of the speaker at higher frequencies due to an increase in inductance.” This, unfortunately, was an error. While there is an increase in top-end extension of a 16-ohm speaker versus an 8-ohm speaker, it is due to an increase in the DC resistance (DCR) and not due to an increase in inductance. While the increase in inductance could actually cause a slight loss in high frequencies, the DCR is the dominant factor here, and its effect increases faster than the inductance. Sorry for any confusion.

Jeff Bober

Jeff Bober, one of the godfathers of the low-wattage amp revolution, co-founded and was the principal designer for Budda Amplification. Jeff has just launched EAST Amplification. He can be reached at pgampman@gmail.com.

For many years, I’ve been playing hard rock with British master-volume amps (i.e., Marshalls). Lately I’ve fallen in love with the sound of a Marshall 1959SLP. Besides enjoying the slight breakup distortion, I like the amp’s great dynamic range. My picking pressure can make the amp go from a clean, chimey sound with a “hollow” low end that really cuts through to a great mid-rangey, crunchy, distorted sound. I’ve tried to replicate this with master-volume amps like a Marshall JVM or Orange Rockerverb by reducing the gain, but I just can’t get the same dynamic response. Do non-master-volume amps inherently have a better dynamic response? Would class A amps come closer to what I’m looking for?

Len

Hi Len

Nice observation. You’re correct that most amplifiers designed with master-volume controls don’t have the dynamic range and headroom of non-master-volume amps, but it’s more than simply a case of a master-volume control being inserted into the circuit. Here’s my opinion on the subject.

Let’s use your two-channel, four-input model Marshall 1959 as an example. Say you want to run the volume controls on channel 1 and 2 at high levels to achieve a bit of preamp overdrive, but need to play at a less-than-ear-shattering level. (We’ll assume you’ve jumpered channels 1 and 2 together, because that’s where the magic lies in this amp.) If we were to modify this amp and properly install one of several different master-volume circuits, you could lower your volume level with decent results, albeit with a reduction of dynamic range.

This loss of dynamics happens for two reasons: You’re saturating the preamp section, and the master-volume circuit is preventing the full signal from reaching the output stage. If you crank the master volume to 10 and set the volume controls on channel 1 and 2 as you currently do, the amp would sound virtually identical to the way it does now. At this point, you’d realize that the lack of dynamic range is not entirely a result of having a master-volume control in the circuit.

So what’s causing this lack of touch sensitivity and extreme playing enjoyment? The basic answer is “too much stuff!” Most master-volume amps are designed with additional gain stages in the preamp section to achieve a considerable amount of front-end gain and produce a substantial amount of overdrive. This usually means more instances where the signal is amplified, filtered, attenuated, altered, controlled in some way, and then re-amplified and treated all over again. More circuitry means more places for the signal to get lost.

All of this detracts from the signal’s purity and dynamic range. Some of the very early “British”-style master-volume amps (such as the Marshall 2203) are not as guilty of this and can have some pretty decent dynamic range and headroom, but the more current amplifier designs are generally horses of a different color. For me, this is a great argument in favor of “less is more” design. If you want a big, open, responsive, chimey, full-bodied sound, the more basic the circuit, the better the result. As you’ve already found out, your Marshall 1959 is a prime example of this design philosophy.

Regarding your question about a class A amplifier possibly coming closer to what you’re looking for, first let me say I believe the only true class A amplifier is one with a single-ended output stage, such as a Fender Champ. That said, while most output stages that builders describe as class A can be responsive and sound pretty dynamic, the amp’s tone is also going to depend on the design of its front end. Too much stuff in the signal path could equal too little tone.

A quick clarification: One of the sentences in my last column regarding speaker impedances read, “A higher number of turns in the 16-ohm coil may slightly increase the response of the speaker at higher frequencies due to an increase in inductance.” This, unfortunately, was an error. While there is an increase in top-end extension of a 16-ohm speaker versus an 8-ohm speaker, it is due to an increase in the DC resistance (DCR) and not due to an increase in inductance. While the increase in inductance could actually cause a slight loss in high frequencies, the DCR is the dominant factor here, and its effect increases faster than the inductance. Sorry for any confusion.

Jeff Bober

Jeff Bober, one of the godfathers of the low-wattage amp revolution, co-founded and was the principal designer for Budda Amplification. Jeff has just launched EAST Amplification. He can be reached at pgampman@gmail.com.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

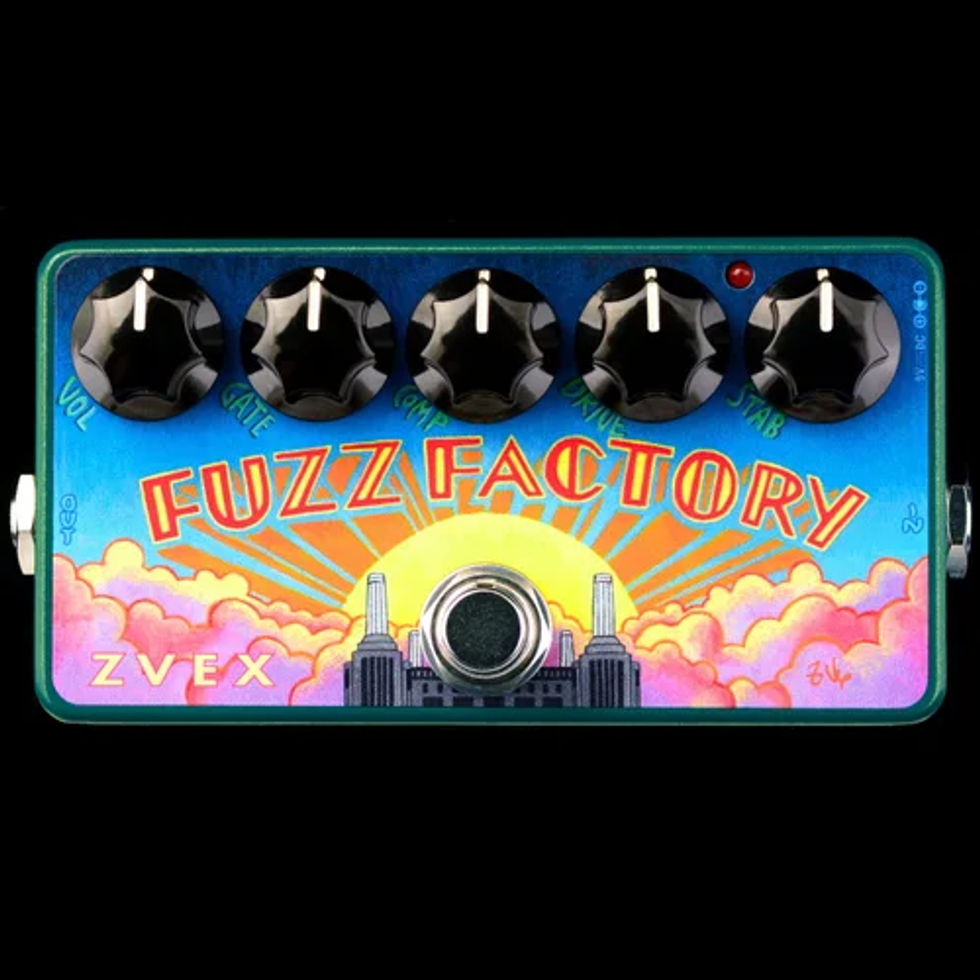

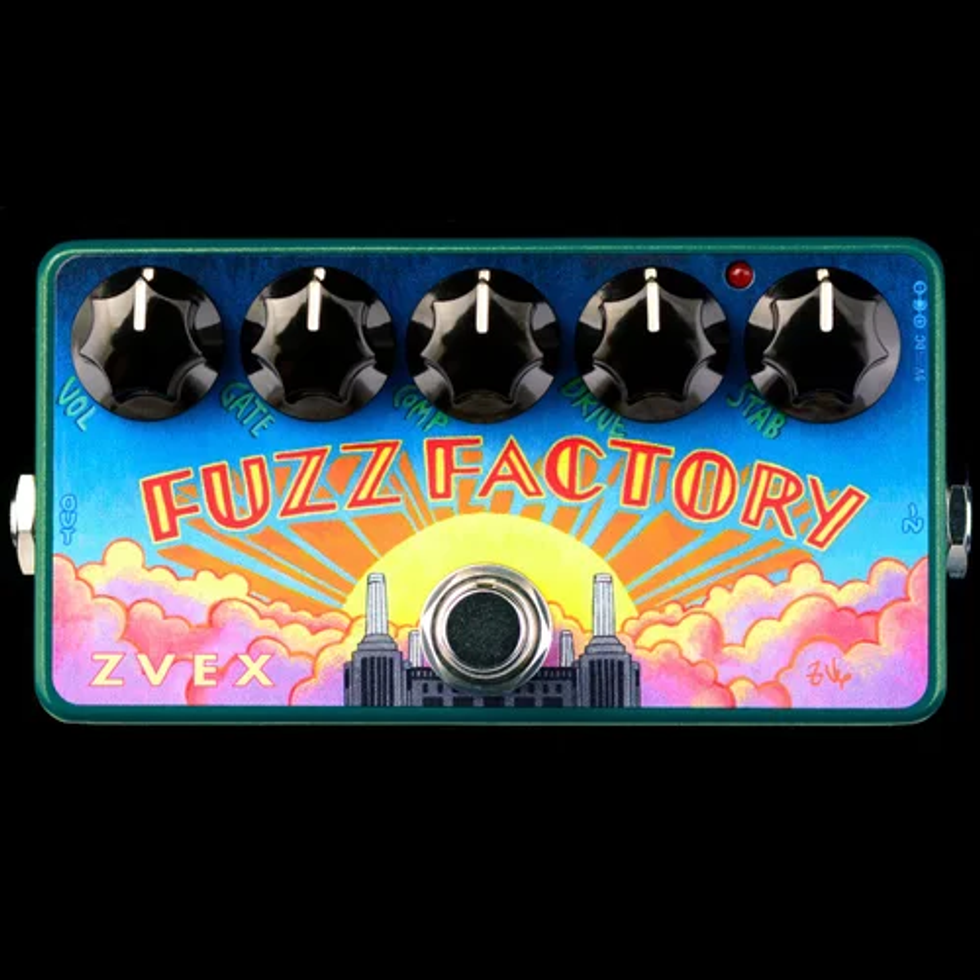

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig