There’s a definite, almost tangible, musical force that surrounds Prince. When musicians are offered a chance to pass through the Purple One’s sphere of influence, rarely do they say no—even Miles Davis had a late-night jam inside Paisley Park Studios (Prince’s $10 million-dollar recording compound located in Chanhassen, Minnesota). In late 2012, Prince asked drummer Hannah Ford Welton to help recruit a guitarist for a rock-oriented project he was putting together. As Welton was cruising YouTube she came across Toronto guitarist Donna Grantis and her fusion trio play Billy Cobham’s “Stratus,” a tune that was already in Prince’s live show. At the time, Grantis was making her name as a forward-thinking, jazz-inspired rocker in the clubs with her eponymous group. Once Prince saw the video he invited her to Paisley for a jam. The chemistry was immediate. “Within a week I had booked a one-way ticket to Minneapolis,” remembers Grantis.

In the 18 months since that fateful jam, 3rdEyeGirl—the trio of Grantis, Welton, and bassist Ida Nielsen—have become a powerful and funky rock ’n’ roll outfit. Without the behemoth of the New Power Generation’s 11-piece horn section, the group is more nimble, explosive, and so incredibly full of energy, it’s hard to believe it’s just a quartet. “Because we are so small, just the four of us, there’s a lot of room for improvisation. We can really stretch things out,” mentions Grantis. PLECTRUMELECTRUM, the group’s first full-length album shows off the bombastic playing of Welton, the hard-driving bass lines of Nielsen, and of course the adventurous and inventive playing of Grantis. This alone would make for a formidable trio, but with Prince’s Hendrixian, wah-fueled explorations, the result sounds like Jimi fronting Led Zeppelin with a James Brown swagger.

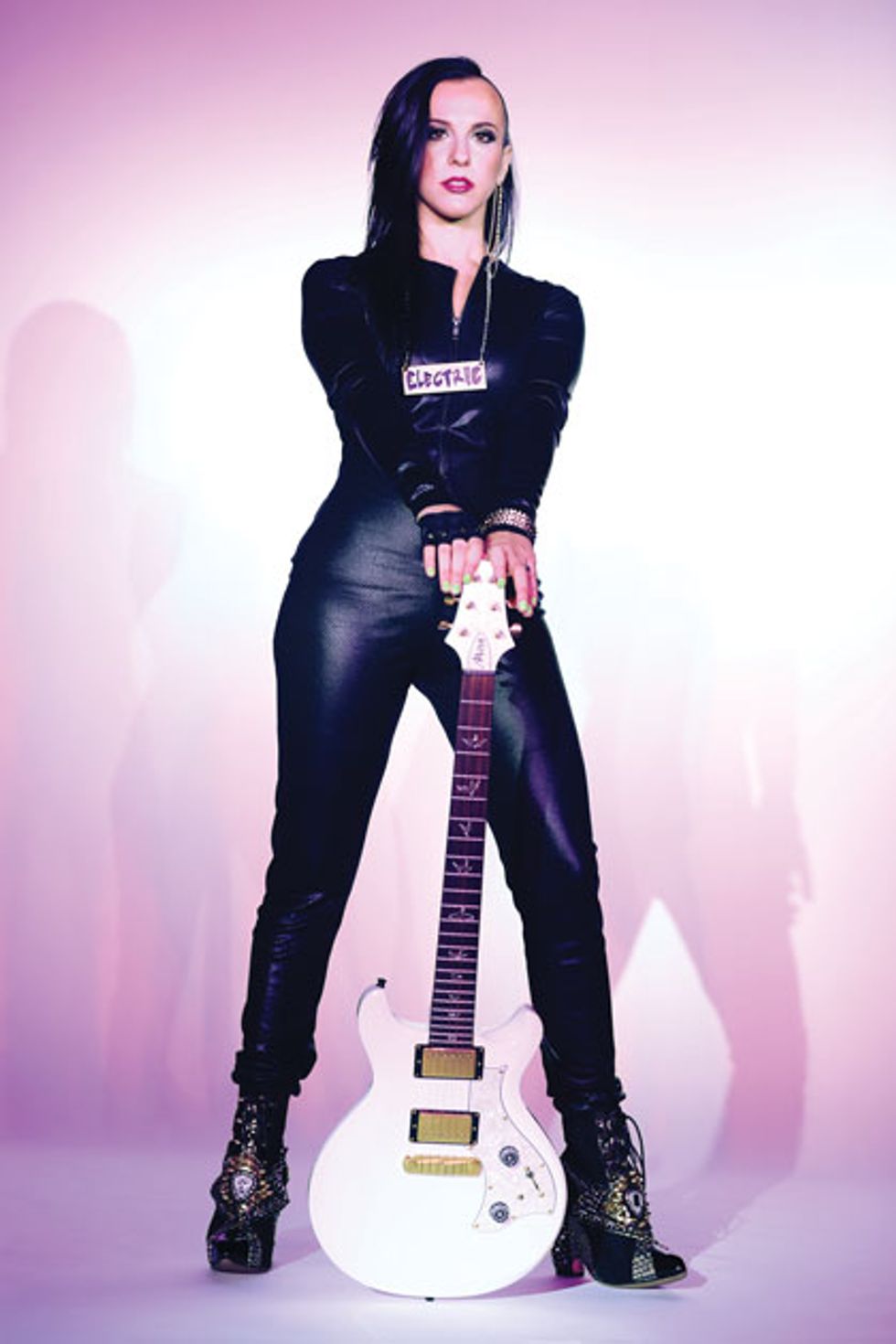

Grantis gives Premier Guitar a glimpse of life inside Paisley Park, explains her love for vintage Traynor amps, and shares guitar tips from Prince himself.

The album is finally out. Was this something you started working on as soon as you joined the group?

It was one of those things where when we started recording the album, we didn’t realize what we were doing. We just set up to rehearse and everything was miked. Recording is just part of our day-to-day existence. It wasn’t until we started hearing the songs with vocals that we thought there was something bigger being planned. Out of everything we recorded, Prince asked us to find 12 songs that we thought went together really well. I’m sure Prince had a master plan, but when we were recording we thought we were just cutting takes.

Absolutely. The really cool thing was that it was recorded live with all of us in one room playing together. We just had to nail takes that we would keep. If one person made a mistake it was like we all made a mistake.

With a musician as iconic as Prince, it’s nearly impossible not to be aware of his music. Was he a formidable influence on you growing up?

He was a huge influence on me. Before I got the call for this gig people would ask me, “If you could play with anyone, who would it be?” My answer was always Prince. About a year before I went to Paisley I actually saw him play in Toronto and then one of the infamous after-show jam sessions. Playing with him is literally a dream come true.

After more than a year of recording and some touring, is there a fair amount of music that didn’t make the album and was put into the vault?

[Laughs]. Yeah, the vault is real!

Can you describe what it’s like at Paisley Park from a musician’s standpoint?

It’s the ultimate creative space. Every day we go in to the huge soundstage. It’s like a live music venue. Sometimes we open up on the weekends on short notice and invite people in to have dance parties, listen to new music, or even have breakfast. We played a show once called The Breakfast Experience. It was in support of Prince's single, “Breakfast Can Wait” and we performed in our pajamas at four in the morning to a packed room. Everyone was in pajamas and pancakes were served—it was pretty crazy. There are a number of recording studios. Of course, there’s a lot of purple. There’s a ping-pong room. That’s usually where we unwind. Prince and Ida go at it. Since the first day we all arrived, our ping-pong skills have greatly improved.

"Because there's so much ground to cover sonically, and tonally, I needed to have all the essentials in front of me," describes Grantis about her pedalboard.

How structured are the rehearsals?

Every day we have new things to work on and new goals to accomplish. Sometimes it’s working on new arrangements or lifting songs, putting a setlist together, recording, or jamming out on different grooves. It’s amazing to be able to do that together every day for hours on end.

When Prince brings in a song, is it a completed demo or just a few riffs?

Most of the time it would be jams that we would learn really quickly. He would come in, show us something, or maybe give me a chord progression. Prince really left a lot of room for us to contribute to the arrangement, to decide on our tone, how we would play things, or what inversions to use. Sometimes we would just record songs without playing them all the way through. He would just queue things on the spot. That really kept us on our toes. We would jam on parts for a while to really lock in the feel. Other times he's giving me directions like “Use the wah on this.” And then I just take it from there.

Donna Grantis' Gear

Guitars

PRS CE 22 “Elektra”

PRS S2 Mira

PRS 513

PRS Starla with Bigsby

PRS SE Angelus

Effects

Boss RC-30 Loop Station

Line 6 DL-4

MXR M159 Stereo Tremolo

MXR Micro Amp

Boss BD-2 Blues Driver

Fulltone OCD

Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer (modded)

Fulltone Octafuzz

Foxrox Octron

Electro-Harmonix Micro Q-Tron

TC Electronic Hall of Fame Reverb

TC Electronic Flashback Delay

TC Electronic Vortex Flanger

Boss BF-3 Flanger

Ibanez DML20 Modulation Delay III

Fairfield Circuitry Randy’s Revenge

Boss TU-2 Tuner

Fulltone Deja Vibe MDV-2

Jim Dunlop Eddie Van Halen Signature Wah

Ernie Ball volume pedal

Amps

Early ’70s Traynor YBA-1 (modded by Pat Furlan)

Strings and Picks

D’Addario .010–.046

Steve Clayton Delrin .73 picks

EBow

It seems like there's this line between an extremely tight arrangement and a free-form jam.

He’s a master bandleader and we’ve really learned how to communicate onstage. We always keep our eyes on him. He could break things down at any time, queue solos at anytime, stretch out sections—anything can happen. Yeah, the other really cool thing is that he wrote the songs on PLECTRUMELECTRUM specifically for us and with us in mind knowing our styles and musical personalities.

The band also went out on a few tours of small club shows. How important was that in developing these songs?

I think in terms of playing live it just really solidified the vibe of the band and the energy we put behind those tunes. We actually recorded the songs before playing them live. During the tours we only played a couple of songs from the album. The rest of the material went all the way back to Prince’s first album. The interesting thing is that all of those songs were arranged for the four-piece band. That was really cool because a lot of the songs have horns and arrangements with keys and synth sounds. We had to take those songs and figure out how to make them sound massive with only four people.

What guitar did you use on the album?

I used “Elektra” on the entire album, which is a PRS CE 22. That’s been my main guitar since I was a teenager. Plus, it’s purple—so I guess it was meant to be.

You cover an amazing amount of sonic space with all the different tones in your live show. I imagine your pedalboard is pretty sizeable.

I have a massive pedalboard that Craig Pattison built me specifically for this gig. One of my techs calls it the starship. It’s three pedalboards, all connected together. Something like 20 pedals. Because the group is only the four of us, there’s so much ground to cover sonically, and tonally. I wanted to have all the essentials right in front of me.

What pedal, or combination of pedals, do you use for your lead tone?

I actually use a lot of different combinations and when thinking about the solos on the album, I wanted them all to be slightly different, tone-wise. For example, there’s a song called “AINTTURNINROUND,” and there’s a part where the guitars are feeding back and the lyric is “What you are listening to now is an ultrasound of Donna’s brain.” I stepped on almost everything. That was probably an Octa-Fuzz mixed with an OCD and a TC Electronic Flashback Delay with a Vortex Flanger and a Line 6 stereo delay—at minimum. For something like “ANOTHERLOVE” that was pretty much straight OCD plus wah with a little bit of the Flashback Delay. For “WHITECAPS” I wanted to get a warmer tone so I used reverb with an Ibanez Tube Screamer that was modded for me.

Rehearsals with Prince can be pretty intense. “Sometimes we are given a list of six songs to learn for

the next day. Or learn them by dinner!," mentions Grantis.

What was the mod?

A guy from Toronto named Pat Furlan did it. I’ve worked with him a lot to mod my amps as well. I was looking for added warmth, a greater range of attack, and longer sustain. Basically, I would describe to him a sound, and then he would work his magic until we got to the right place. On the album, I played through vintage Traynor amps from the ’70s that were handmodded by Pat. We went through the process and he knew who my influences were and what kind of sound I liked. He modded the amp for me and after we went back and forth a few times, we landed on the right tone.

What’s a typical day at Paisley Park like for you?

We go in and play all day, break for dinner, and then go back in and play either late into the night or early into the morning. We’re always working on new songs—it's become just part of the process. Over the past year and a half it’s a lot easier for me to learn songs quickly and remember them. I lost track of how many songs we’ve learned.

Do you chart them out?

I chart them out and we usually make our individual charts but we lift by ear for our parts. Then I bring those to rehearsal and then the arrangement will get changed or really picked apart. Then I make notes and really try to commit it to memory at that point. Sometimes we are given a list of six songs to learn for the next day. Or learn them by dinner! I find that charts can be really helpful as a starting point. There’s always a period of internalizing music and that just comes from playing it and listening to it a ton.

YouTube It

During 3RDEYEGIRL’s quasi-undercover tour of the U.K., the group often opened the show with a reimagining of Prince’s classic, “Let’s Go Crazy.” Donna Grantis takes a ripping solo at 4:18.

Is there a particular song on the album you feel especially connected to?

“PLECTRUMELECTRUM” is really special. It’s a song that I wrote that Prince rearranged. It’s an instrumental and everyone’s musical voice and personality really shines through. Hannah has some wicked drum fills, there’s this heavy bass groove, and Prince and I both solo. It was a real honor to have Prince arrange a song I wrote. I definitely have special memories about every song. One in particular is “ANOTHERLOVE.” That was a song that we were recording at a three- or four-in-the-morning jam. Prince has a way of really pulling out the best in everyone. I really thought I would have to spend some time working out something for that since it’s a giant solo in a Prince song, but he wanted to record it right on the spot. Prince and I are trading fours, and as a guitar player, that’s so much fun.

Have you picked up any gear tips from Prince?

He can play any guitar through any amp and make it sound incredible, but I think one of the sounds I really like is how he uses a flanger pedal. There's a lot of room for feedback and really cool sounds. Other than the melodic side of things and note choices, I’ve also really learned a lot from him on how to create soundscapes to end tunes or between phrases or before hitting a solo.

I’ve learned so much from him about when to play and when not to play. Plus, how to make every note count and play everything with conviction. I’ve learned a ton about funk and rhythm guitar. I’ve put together a “funklopedia” of all the funk lines and riffs I’ve learned from him. It’s so incredibly tight and precise and there’s such a special way of approaching that type of playing in terms of the attack and rhythms, but loose at the same time. Hearing Prince, Hannah, and Ida play still blows my mind. I just love where things are at right now.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.