Sonny Sharrock, whose guitar playing harnessed the explosiveness and beauty of a summer thunderstorm, recorded Seize the Rainbow in 1987. By then, he'd been doing just that for more than two decades, using his guitar as a prism to reflect his glorious, Technicolor vision of music and life. Along the way, he helped invent free-jazz guitar.

The flautist and bandleader Herbie Mann, who employed Sharrock and his then-wife Linda in the late '60s, referred to the unfettered guitarist as “my Coltrane." And, indeed, Sharrock's own awakening as a musician happened as a teenager when he heard John Coltrane's performances on the immortal Miles Davis album, Kind of Blue. Although it took until 1966, when he was 26 and playing with Coltrane's sax-wielding friend Pharoah Sanders, for the light bulb that illuminated his approach to ignite.

“I remember the very day I learned to play 'out,'" Sharrock told me when we first met in 1988. “Pharoah had this technique of overblowing the horn. It sounded like very fast tonguing, like a buzz saw. I tried to copy it by trilling on the guitar and found that I could get a huge sound, but more human, like a voice. Then I tried to stretch it by pulling strings and bending notes, and that was the beginning."

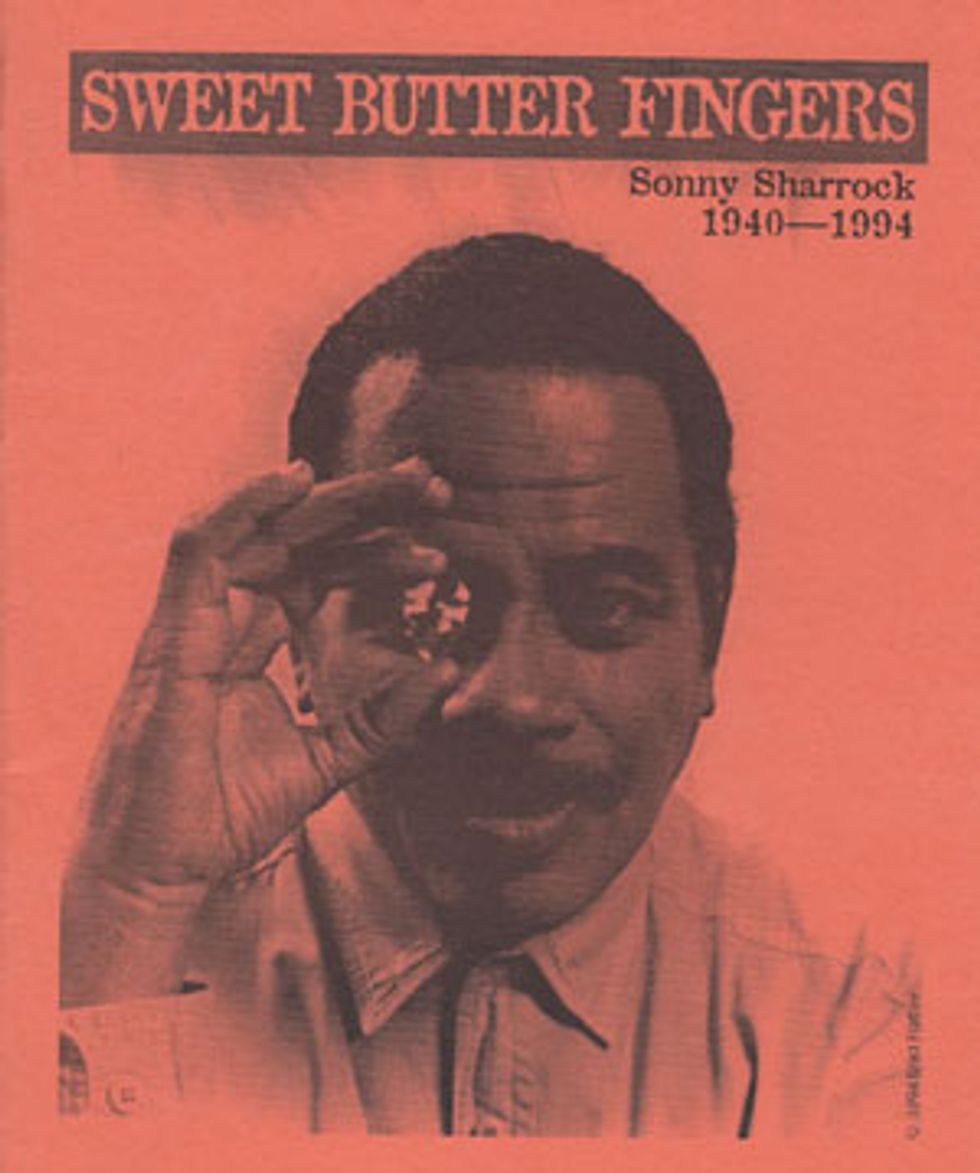

The end came too soon. After decades of struggle—even leaving performing and recording to work as a chauffeur and a music therapist for mentally challenged children—Sharrock died just as the world's doors were fully opening for him and his music. Three years after releasing 1991's majestic Ask the Ages, a graceful, expansive, and clamorous return to the '60s free-blowing aesthetic that had inspired his beginnings—an album that ended up on major jazz and rock critics' top 10 lists and propelled Sharrock toward stardom—he was on the verge of signing his first major-label deal. To prepare for that milestone, he was exercising at his home in Ossining, New York—the small city in the shadow of the notorious maximum-security prison called Sing Sing—and dropped dead from a heart attack. He was 53.

Sharrock left behind an amazing legacy of recordings. As a sideman, he'd played on Miles Davis' A Tribute to Jack Johnson paired with John McLaughlin, and he made seven albums with Mann, including the influential Memphis Underground. He also played on Sanders' 1966 classic Tauhid, Wayne Shorter's innovative Super Nova, Don Cherry's Eternal Rhythm, and discs by Ginger Baker, Roy Ayers, soul/avant jazz-fusion band Brute Force, and new-wave avant-funk outfit Material, among many others.

Before his '80s re-emergence, Sharrock had recorded two albums as a leader—his 1969 debut Black Woman and 1970's Monkey-Pockie-Boo—and cut 1975's Paradise co-billed with Linda Sharrock. When he returned to full service, he did it with passion, making seven albums from 1986 to 1993, ranging from the all-solo instrumental Guitar to the blithe, melody possessed Highlife to the soundtrack for the cartoon Space Ghost Coast to Coast. He was also a member of Last Exit, perhaps the wildest bunch of free-improvising gunslingers to ever take a stage, along with bassist/auteur Bill Laswell, drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson, and reedman Peter Brötzmann. They'd never played together until Laswell summoned them to a festival in Köln to perform and simultaneously record an album in February 1986. In Last Exit, Sharrock delivered some of his most furious, unpredictable solos—often employing the solid Stevens bar he used for slide to conjure the kinds of sounds one would expect to emit from the gates of hell. (And the Pearly Gates, too, because Sharrock had a gift for creating angelic melodies.)

By the Horns

The great American improvising guitarist Henry Kaiser bought his first guitar and slide the day he heard Sharrock on Sanders' Tauhid. Kaiser went on to play with Sharrock (and scores of others), and recently released the tribute album, Echoes for Sonny, with fellow Sharrock cohort and guitarist Robert Musso. He summarizes the late genius thusly: “Sonny was the kind of guitarist who comes along once in a generation—if that—as special as Hendrix, Django, and B.B. King. A magical person. No one has made a more original statement on the instrument. Sonny had as much heart as B.B. or Carlos Santana. He stood in the middle of what was happening in black jazz in the '60s, socially and politically, and in the beginning of free jazz. Without Sonny Sharrock, there is no Vernon Reid, no Sonic Youth … so many things people have embraced musically.

“And his slide playing is unprecedented," Kaiser continues. “It's technical and non-technical at the same time, so it was accessible to me the moment I heard it. Just how original was he? Well, if you look to B.B. King, first there was T-Bone Walker. For Jimi Hendrix, you've got the influence of Curtis Mayfield and Muddy Waters. For Sonny, there ain't nuthin'. He's the first guitarist with his footprint on the moon."

Factoid: After Sharrock's death in 1994, the Black Rock Coalition held a memorial concert in his honor in New York City's Central Park. This booklet was produced for the event.

Sharrock's Earthly arrival was on August 27, 1940, in Ossining, where he spent much of his life. “Dad's full name was Warren Harding Sharrock, Jr., after my grandfather, but he never liked that name," says his daughter, Jasmyn Sharrock. The stories of the 29th president's affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan were a thorn, and Sharrock quickly adopted what his family called him as his handle.

His first musical obsession was vocal groups, like the Moonglows and Orioles. “The greatest thing I'd seen until then was Red Ryder and Little Beaver on their horses," Sharrock recalled, “but these groups were the hippest. They had matching suits, did coordinated steps, and they sounded incredible." At 14, his baritone singing earned him a spot with an integrated group of neighborhood kids who called themselves the Echoes. “The other guys were a lot older, but I'd just pencil in my moustache and go right on into the club."

A few years later, in 1959, he was listening to Symphony Syd, the hot jazz DJ on New York City's WJZ, and heard Kind of Blue. “I saw Miles' band that summer and I was gone from that moment on," Sharrock recalled. He began a lifelong obsession with horns and drums. “But I couldn't afford either, and I had asthma, so I knew I couldn't play the saxophone." His consolation prize was his first guitar, which he purchased in 1960, and he split Ossining for Boston and the Berklee College of Music in '61.

“There were 26 guitarists enrolled, and I was ranked 25th," he recounted. “Then the 26th guy left and I was at the bottom." He didn't stay much longer. Armed with the basics of music theory, Sharrock moved to California in 1962 and lived in a trailer with several other struggling musicians while trying to pick up gigs and sessions. But not before suffering one more indignity.

“I got into a band and we worked for just one night at a coffeehouse in Cambridge," he said. “Sam Rivers and Tony Williams were in town and decided to sit in, and they destroyed us." He laughed and shook his head. “They played 'Milestones' at a tempo I'd never realized existed!"

Ultimately, he found his musical home in mid-'60s New York City. “When I got there, I ran into Sun Ra on 125th Street and I asked to study with him. He said, 'Come by.' So I went to his place and Pat Patrick, Marshall Allen, and all these heavies from his band were there, and Sun Ra showed me two movies. That was the extent of the lesson. Real weird! But while I was there, they got a call from [Nigerian drummer and bandleader] Olatunji about a gig. I heard Pat say, 'Yeah, I've got a guitar player here.' I thought, 'He can't be talking about me.' That's how I ended up working with those guys. They were very nice to me, because I didn't know what the hell I was doing."

So Sharrock's bona fide apprenticeship on the bandstand and in the studio began, including the important work with Sanders that set him exploring dissonance, distortion, slurred licks, and skittering, screaming slide, as well as melodic excursions inspired by horn players, classical music, and blues. His tone grew darker, richer, and bigger, and would continue to do so throughout his career as he upgraded gear and further defined himself. He also began using distortion pedals, so he could compete with the sound of an overblown tenor sax.

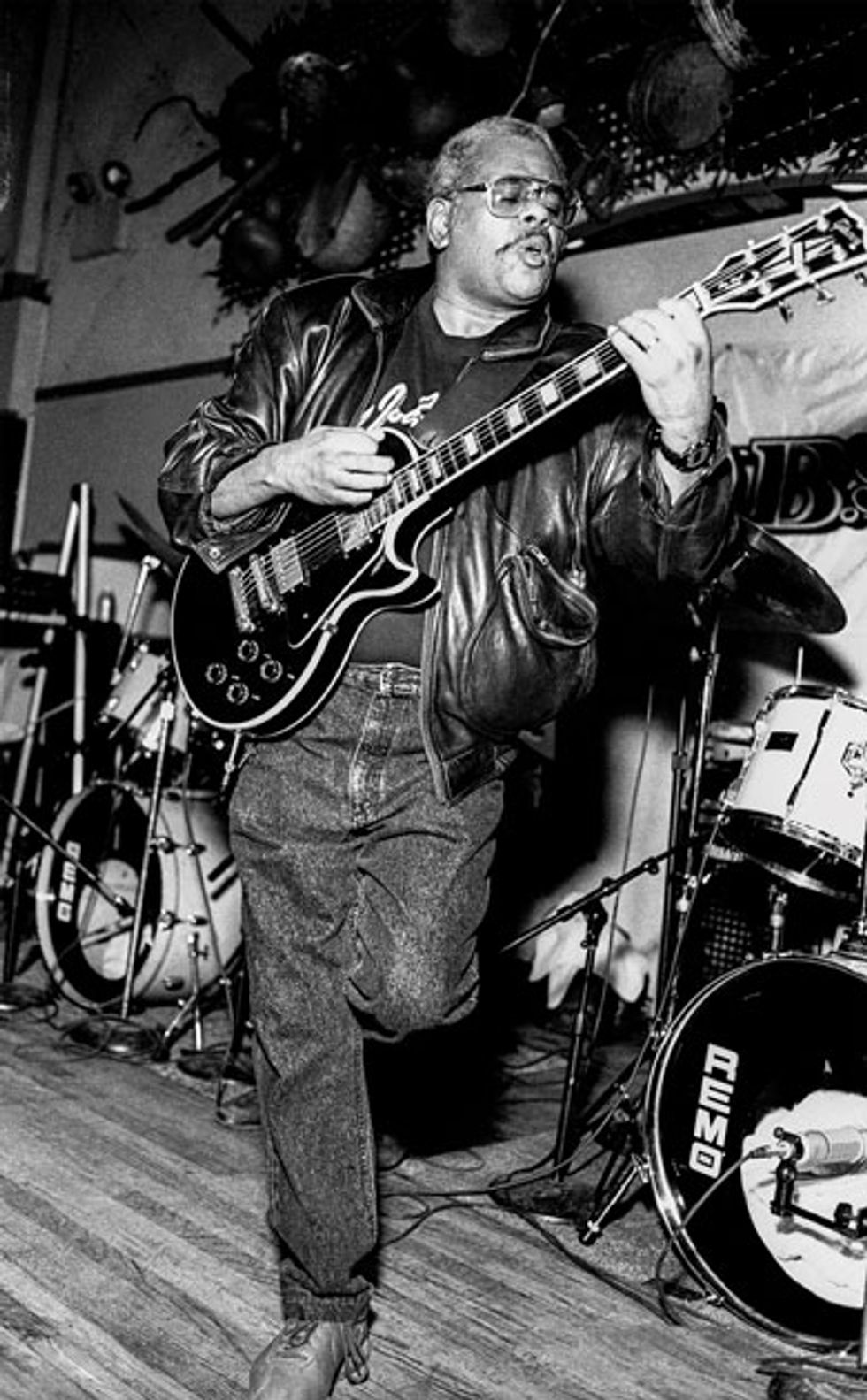

In mid-flight during a 1992 concert, Sharrock fused energy and intellect into a breathtaking dialog with his audience. Note his T-shirt, from a Last Exit performance at Johnny D's in Somerville, Massachusetts, on February 2, 1990, one of the band's three U.S. performances. Photo by Jack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotos

Clearing the Room

Sharrock was recording and performing with reed player Byard Lancaster when he got a telegram—he was so broke that he didn't have a phone—asking him to call Herbie Mann.

Mann fused jazz and pop, and had been among the musicians who'd popularized the bossa nova in the States during the early '60s. He sold a lot of records across a spectrum of listeners. He also had broad tastes and was looking for a connection within his own music to the free jazz sounds that were exciting him. Soon, Sonny was getting the spotlight once at every Mann concert, and he was joined there by vocalist Linda Chambers, who he'd later marry, when she was also hired for Mann's group.

“I'd reached a point where I wanted to have some contrast in the band," Mann told me in 1988. His audience had not. “The reaction was often hate—total hate," Mann said.

Sharrock remembered a gig with Mann at a Florida jazz festival. “It was at a marina, and all these people came in yachts," he said. “In the middle of Herbie's set, Linda and I came out to do 'Black Woman'."

The song was the title track to Sharrock's debut album, the result of a deal Mann has brokered with the Atlantic Records subsidiary Vortex. “They all sailed away," the guitarist recalled, chuckling.

Decades and an upswing in his popularity didn't necessarily change all audiences. When he and Henry Kaiser took the stage to play duets at an Italian jazz festival in 1987, following the staid Modern Jazz Quartet, “the audience was like a tidal wave," Sharrock recounted. “We cleared the room instantly. My [second] wife, Nettie, cried, because she'd never seen anything like that before." He laughed, gently. “I said, 'C'mon, that's nothing! Do you want me to clear out the ushers, too?'"

Humor was another of Sharrock's trademarks. And his friends and bandmates loved him for his wicked one-liners and playful skewerings. “It was as if I was on a laughing-gas high," recalls Pheroan akLaff, one of the two drummers in Sharrock's juggernaut Seize the Rainbow band. “If we went on the road, there would be continuous Don Rickles-style jokes hurled about you from the moment of airport check in until we said goodbye. In fact, I don't ever remember him saying goodbye, unless it came in an insult. That was his way of expressing love."

His daughter Jasmyn also loved Sharrock for his playful spirit. Dad was by no means the disciplinarian among her parents. He encouraged her to dance as they listened to music together, and took her on frequent excursions into New York City. “The time he spent in Manhattan shaped him as a young man," she says. “He wanted me to experience the heartbeat of the city, and because of that I became a city rat as an adult and have never lived in the suburbs."

At our first meeting, I asked Sharrock how he felt about his decades of struggle. His reply: “I've been trying to sell out for years, but nobody's been buying."

And despite Sharrock's avowal to “find a way for the terror and the beauty to live together in one song," there was also humor in his music. It was woven into the grinning, peppy melody of “Blind Willie," a sweet 'n' droney composition on his first album, and the chipper theme—and even the title—of his Seize the Rainbow tune “The Past Adventures of Zydeco Honey Cup." He also laughed and joked with his audiences—often with pointed wit. A video from a 1988 show at the original Knitting Factory, his New York home base in the '80s, features this song introduction: “This is dedicated to the South African government, the Israeli government, and those brothers that are gonna git yo' ass on the way home. It's called 'Stupid Fuck.'"

But he had nearly a decade of hurdles to clear before becoming a darling of the downtown Manhattan music scene. Driven to experiment with pop due to lagging record sales and gigging opportunities, he and Linda, an astoundingly potent vocalist who, like Sonny, worked in sheets of sound rather than conventional language, made the album Paradise. Sonny declared it a disaster, and the disc headed straight to the cutout bins. Today, Paradise is appreciated for its beauty and riskiness, but the guitarist considered the album on Atlantic's Atco subsidiary a self-betrayal of the creative aesthetic he'd forged.

“I worked hard to be me," he declared. “I like drums and I like Coltrane. People used to get mad at me because I'd get hired for a gig and I'd say, 'I ain't gonna play chords. That's guitar. I'm a horn player. I just play a fucked-up horn.' "

In 1978, he put down his “horn"—at least in public. He and Linda got divorced and he moved back to Ossining. “I worked with disturbed kids for a while, which was very demanding," he said. “Then I got a job as a chauffeur. Not a bad gig, but not what I'm supposed to do." He also remarried, to Jeanette Hill, and they had Jasmyn.

Thankfully, Bill Laswell knew what Sharrock was supposed to do. He'd fallen under Sharrock's spell in his early teens. “In high school, when we first heard him, it was on Herbie Mann records," Laswell says. “When Sonny's solo came on, we'd pick the needle up off the record to see what was wrong. It sounded like the guitar exploded." At age 15, Laswell hitchhiked from Michigan to the Newport Jazz Festival and saw Sharrock play with Mann. “He made a great impression on me," Laswell recalls.

The bassist/producer caught one of Sonny and Linda Sharrock's final gigs in a small club after moving to New York City in the late '70s. He also got Sharrock's number. In 1981, he used it, inviting Sharrock to come play in the punk clubs as a guest with his band Material. Sharrock also played on the group's debut album, Memory Serves—a gloriously fractured mix of rock, free improv, and funk grooves.

While his own star rose as a producer for Mick Jagger, Fela Kuti, Peter Gabriel, and others, Laswell dedicated himself to nurturing Sharrock's comeback, producing Guitar and Seize the Rainbow, and organizing Last Exit. And Sharrock, thus encouraged, assembled a quartet around the rhythm section of drummers akLaff and Abe Speller, and bassist Melvin Gibbs, who's gone on to play with the Rollins Band and currently co-leads the ambitious jazz group Harriet Tubman.

Seize the Rainbow was unprecedentedly hard-rocking jazz: less ornate and overtly virtuosic than the Mahavishnu Orchestra and other volcanic fusion outfits, while more rooted, basic, and expressive—at least until Sharrock took off on one of his slide solos that seemed destined for Pluto. Live and on album, he drove his guitar to unpredictable places, and yet, within the framework of a few carefully selected notes, could return to a song's core melody in seconds and with perfect, logical balance. It was breathtaking.

Last Exit was the wildest bunch of free-improvising gunslingers to ever take a stage. From left to right: Peter Brötzmann, Sonny Sharrock, Bill Laswell, and Ronald Shannon Jackson.

The Pinnacle

By '87, Sharrock was playing a Les Paul Custom through a Marshall half-stack, sidestepping the hollowbody jazz guitars and Fender amps he'd used in his earlier work, opting for more volume and tube gain instead of an overdrive pedal. “I'd come back from England, producing Motörhead, and I told him about using Marshalls real loud, and he got into it," says Laswell. “When we got to Japan with Last Exit, he had a whole wall of Marshalls and he'd gotten his black Les Paul, and that was his sound." But his sound, even via that classic combination of guitar and amp, was uniquely liquid and colorful—a thick, sweet sonic syrup that could suddenly leap like lava.

Laswell also turned guitarist and engineer Robert Musso on to Sharrock's music. Musso mixed and engineered Seize the Rainbow and most of Sonny's recordings that followed. He also drafted Sharrock to record and gig with his own band, Machine Gun, and they became running buddies.

“He used slightly different guitars and amps every time I recorded him," Musso recalls. “Sometimes I'd use an SM57 and sometimes a Sennheiser MD 421 on his amp, and he'd use Les Pauls and wah-wah pedals set in certain positions to get the tone he was looking for. No matter what he did, it was Sonny and it sounded great."

For Gibbs, Seize the Rainbow was one of the most memorable album sessions he's done. “When Sonny started playing around town again, I started following him until he hired me," says Gibbs, who'd just quit playing in Ronald Shannon Jackson's Decoding Society. “I remember one gig where I said, “Let me just play some shit and see what Sonny does, and I played wild and he just kinda smiled like, 'yeah, I got you,' and played it back at me. Playing with him helped me figure out who I was."

After a handful of shows with Sharrock, Gibbs was instructed to be at Electric Lady Studios at 7 on a night in May 1987. “We couldn't have spent more than two hours recording," he recalls. “We recorded 'Dick Dogs' first, and I was still kind of fuckin' around with my headset during the take, and Sonny was like, 'That's great. On to the next song.' I thought, 'Oh, we're not fuckin' around today!' When we were done, I looked up at the clock and it was like, 'Shit! 10 o'clock!'"

The seven-song Rainbow was edgy, accessible, and adventurous at the same time, and it introduced Sharrock to the rock world as well, earning him a new audience that continued to expand for the remaining years of his life.

Live in New York, cut at a 1989 Knitting Factory show, came next. It was followed by Highlife, which features Jasmyn and her dad on the cover and is Sharrock's most melody-focused album—a calculated effort to boost his audience even more as he worked toward a grand vision of recapturing the glories of '60s free jazz in the studio. Touring behind this succession of albums and hitting the stage and studio with Last Exit kept accumulating the capital he needed to realize that vision. A set of guitar duets with Nicky Skopelitis, who worked regularly with Laswell, called Faith Moves was next. And then Sharrock reached goal in 1991 with Ask the Ages.

With Laswell producing and Jason Corsaro engineering, he entered Sorcerer Sound in Soho with free jazz giants Sanders and drummer Elvin Jones, and Charnett Moffett, a 24-year-old bass wunderkind who nailed the vibe of elder statesmen like Paul Chambers and Percy Heath. The result was a musical perfect storm. In six tunes, Sharrock built a sonic bridge between his own past and future, supported by big, buttery guitar tones that boldly laid out succulent, easily digestible riffs. The guitar and horn unison head of “Promises Kept," the loving melody of “Who Does She Hope to Be?" (written for Jasmyn), and the riveting, intense “Many Mansions" were the work of an artist who'd tied together all the elements of his soul.

Sharrock set the scene for cutting that last, magical tune: “Pharoah was in the glass booth on one side of the room. Charnett was on the other side. I was out on the floor sitting across from Elvin laying down the drone, and I flashed back. Looking at him and hearing him up close, it was suddenly the first time I saw him back at Birdland with Coltrane. And I lost it. I totally lost the tune, because he was playing such a deep, deep groove. I went into a total fan thing and forgot about being a musician, because it was just too good. You can hear my mistake on the record, too, because I wanted to keep that."

Sure, the sound of Ask the Ages was something he'd begun sculpting in '67, but, Sharrock explained, “it wasn't complete at that point. Now it is complete, and it's ready to be heard." And today it's ready to be heard again. Late last year Laswell reissued Ask the Ages on his M.O.D. Technologies label, and it's still stunning and full of heart.

The album gave Sharrock wings. He toured more, and he felt that his playing continued to improve—as odd as that sounded to us knocked-out acolytes. And then, he died. Leaving so much fantastic music unmade.

“I remember him saying that after his grandmother told him he should go to church, he told her, 'No grandma you should listen to John Coltrane,'" says akLaff. “His generation had that clarity. Him, Carlos Santana—they each have the depth of spirituality as their most earnest goal, and to reach it through their instruments and share it with others. That came out in Sonny's playing."

“The biggest thing I learned from being around my dad is to never compromise who you are," say Jasmyn Sharrock. “Integrity is the first word that comes to mind. My dad never changed who he was regardless of who was around. He stood up for what he believed in: doing the right thing and being a kind person. It sounds corny, but he believed if you do the right thing, then things will work out. He was always a class act."

Santana Talks Sharrock

When Sharrock traveled to Japan, he took two Les Paul Customs. One had extremely high action, for practice. The other was set close to the neck, for speed. Photo by Paul Robicheau

Given Sonny Sharrock's relative obscurity and the iconoclastic nature of his music, it's surprising to hear a high-profile artist like Carlos Santana work one of Sharrock's tunes into his sets. Nonetheless, “Dick Dogs" from Seize the Rainbow is occasionally a hard-rocking highlight of Santana concerts, and Carlos says his solo for “Bliss" draws straight from the well.

“I was ready to do a tour with him, record with him, and then he left us," Santana explains. “We talked a few times on the phone after he found out I was fully into him, and he was such a gentlemen and very gracious and encouraging. To me, he was a tornado when he played and he left an imprint with his melodies, of course, but I was also into the energy."

The guitar legend says he first heard Sharrock on Wayne Shorter's 1969 fusion classic Super Nova. The next year, Santana caught Sharrock live in Montreux, playing with Herbie Mann. “He had a big 'fro and a fringe jacket and was laying into it, and I was, like, 'Dang, this is a very radical dude!' I couldn't take my eyes off of Sonny, because when he went into his solo it was like Coltrane and Jimi Hendrix, Albert King, John Gilmore, Pete Cosey, and Larry Young all together—interdenominational intergalactic music. It was a thing of beauty. I remember a lot of people got up and left because they were not ready; their minds were, like, 110 and he was 220. I was like, 'This is the shit!' Sonny Sharrock and [P-Funk's] 'Maggot Brain'—that was a new way. So refreshing to hear something so different from Queen, Hendrix, Jeff Beck, or Led Zeppelin, but at that level of mastery."

So Santana sought out Sharrock's recordings, discovering a consistent boldness of tone and purpose—the latter expressed, particularly, in numbers like “Black Woman" and “Portrait of Linda in Three Colors, All Black," which were rallying calls for African-American empowerment and identity, and for pure, heart-expressed sound.

“If you want to get a tone like Sonny Sharrock or Stevie Ray or John McLaughlin, you have to be really willing to die. Right now, right here," Santana relates. “It ain't no pedals that are going to give you that sound. It ain't no amplifier. It ain't no guitar. If you could see like a psychic that going for that next note or that particular solo, you might be checking out … then fuck it, you check out. It means that much to you. Sonny—I would call him a liberator. If you really listen, artists like that can liberate you from your own fear. He's like Coltrane—he's the cosmic lion. And when he roars he wakes people up from the nightmare of feeling limited and unworthy."

Carlos Santana's version of Sonny Sharrock's “Dick Dogs" is off the chain. Watch Carlos get rad with a Stevens bar slide at 5:50—and wail like a banshee on his Paul Reed Smith signature model throughout.

YouTube It

Since Sonny Sharrock died a full decade before the dawn of the YouTube/smartphone era, there isn't a wealth of visual records of his performances. But these three clips sample his creative arc.

Here, Sharrock plays an Italian TV appearance with one of Herbie Mann's Memphis Underground-era groups. Sharrock is playing a Yamaha hollowbody guitar through a silverface Twin Reverb, and cuts loose at 1:45 with flurries, slurs, and trills.

Linda and Sonny Sharrock led their own band for this performance of “Peanut" from Black Woman on the French TV show Jazz Session. Sonny's dynamics, note choices, and chordal outbursts are totally unpredictable, and yet, his and Linda's interplay display their then-shared vision at work.

And here's Sharrock on stage at the original Knitting Factory in 1988 with his double-drums Seize the Rainbow band. He comes out of the gate ripping, alternating between flurries of notes and warm melodies. At four minutes, bassist Melvin Gibbs steers the tune into funk. And when Sharrock breaks out his slide after six minutes, all hell breaks loose!