Stringed instruments without headstocks, from lutes to nylon-string guitars, have existed for ages. It’s even rumored that Les Paul built a headless guitar of his own. But chances are, when you think of electric guitars sans headstocks, you either picture someone from the 1980s in tight pants and big hair playing an original Steinberger, or you envision a tattooed YouTube shredder with a Strandberg in hand. The two brands share many similarities and dominate one of the most controversial electric guitar designs since Leo Fender slapped a pickup into a plank of solid wood.

Until now, headless guitars were a respected but—other than for a brief period in the ’80s—niche product played by only the most adventurous. Recently, though, they’ve enjoyed a meteoric rise in popularity and are giving the legacy guitar models a run for their money. How did such outlandish-looking instruments become so popular? What would possess a guitar designer to “head” down such a radical path? Is this a fad, or is there something to these futuristic-looking instruments? To answer these questions, we’ll have to go back to 1976.

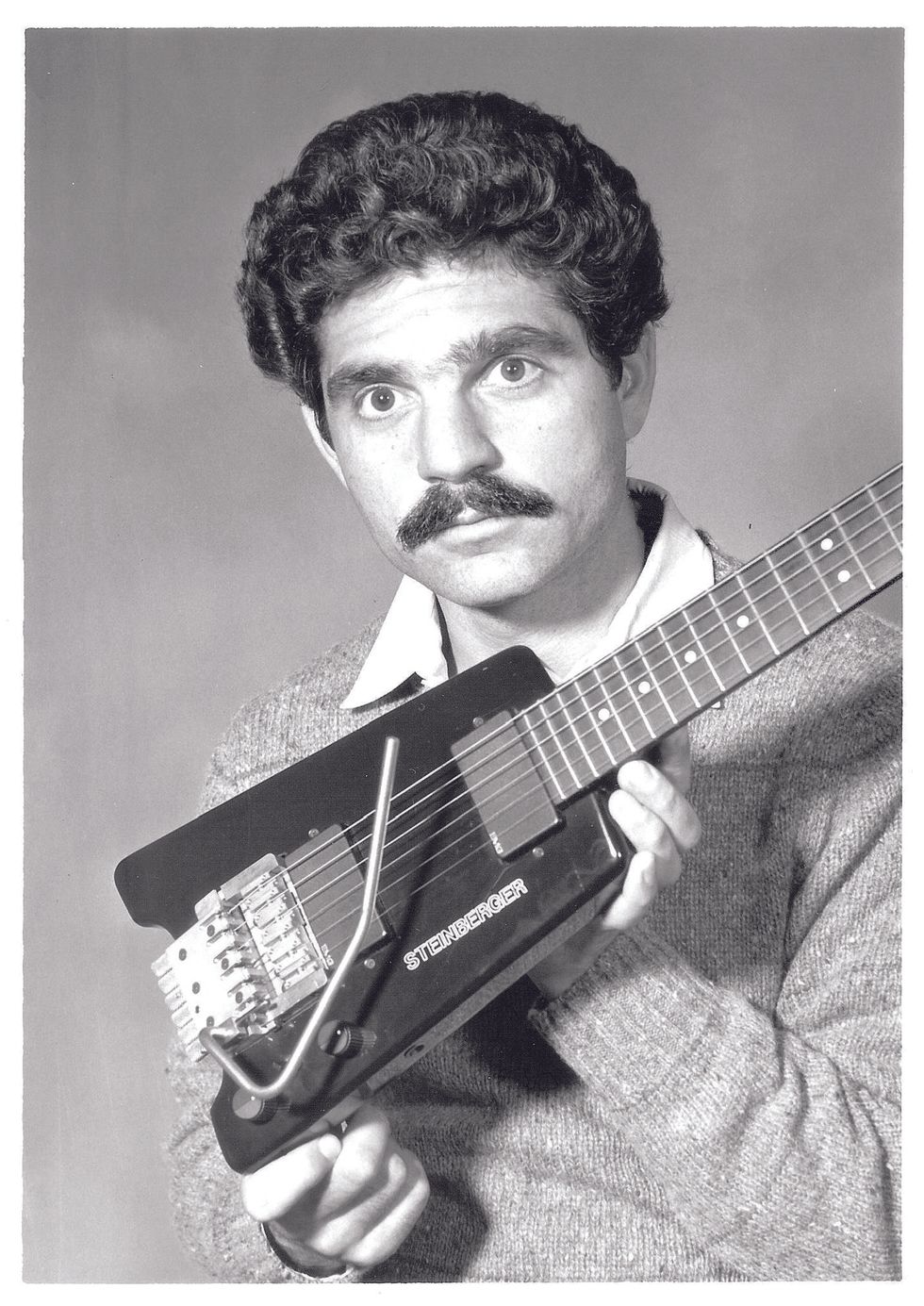

Ned Steinberger

Back in the mid 1970s, then-guitar-builder Stuart Spector wanted to create a new kind of electric bass. He made a serendipitous move and turned to a fellow member of his woodworking co-op to help: Ned Steinberger. Inspired by Ned’s ergonomic furniture designs, he wanted to imbue the new instrument with the same level of comfortable contouring. While furniture and basses might seem like an odd pairing, to Ned, the two are the same.

“I was involved in designing chairs, primarily,” Ned explains. “And a lot of the things I was working with were analogous to bass. I thought, ‘How does it feel? What are the ergonomics? What is the message of the piece?’ The bass guitar was essentially the sexiest chair I could have imagined [laughs].”

Ned Steinberger with his first TransTrem model in 1983. It was pure kismet that Stuart Spector asked Steinberger, then a furniture designer, for help with a bass design back in the mid ’70s. The rest, as they say, is headless history.

Putting their skills to work, Steinberger and Spector created the very first Spector NS bass, and it’s remained a staple of the industry ever since. But as great as it was, in Ned’s mind it still had a few shortcomings that he would address in his very own bass design.

“There’s this neck-dive issue I was working on,” he says. “All bass players are familiar with it, and that’s where I came into the whole thing, with the ergonomics. There wasn’t balance. And I was thinking, ‘This is not working!’” The culprits were the headstock and the added weight of the tuning machines. Ned’s solution was simple. “If you have a weight at the end of a stick and you put it at the other end of the stick, it’s going to change the balance,” he says. He would move the tuners to the body and remove the headstock altogether, giving birth to the modern, headless electric guitar—or bass, in this case.

“These weren’t weird for being weird. They were about trying to make an instrument perform at the highest level, and musicians could relate to that.” —Ned Steinberger

Ned was just getting started. Many more design elements most luthiers hold dear were on his chopping block, including the wood itself. Creating his first prototypes and production models was a gigantic undertaking. But it would soon be worth it.

The Rise of Steinberger

The 1980s were an exciting time for electric guitar and bass. New brands like Jackson, Charvel, and Kramer, along with Floyd Rose’s revolutionary bridge designs, created fertile ground for forward-thinking electric instruments. Trying to capitalize on this opportunity and wanting to avoid running his own manufacturing business, Steinberger tried to sell his new design to more prominent guitar manufacturers. But even in the ’80s, a bass shaped like a paddle was a challenging sell.

“People didn’t understand. These weren’t weird for being weird,” explains Ned. “They were about trying to make an instrument perform at the highest level, and musicians could relate to that. But when I first brought it to a lot of the shops, they all said, ‘No. We don’t want any of that shit. We can’t sell it.’ They weren’t being mean to me. They were just laying it out there.”

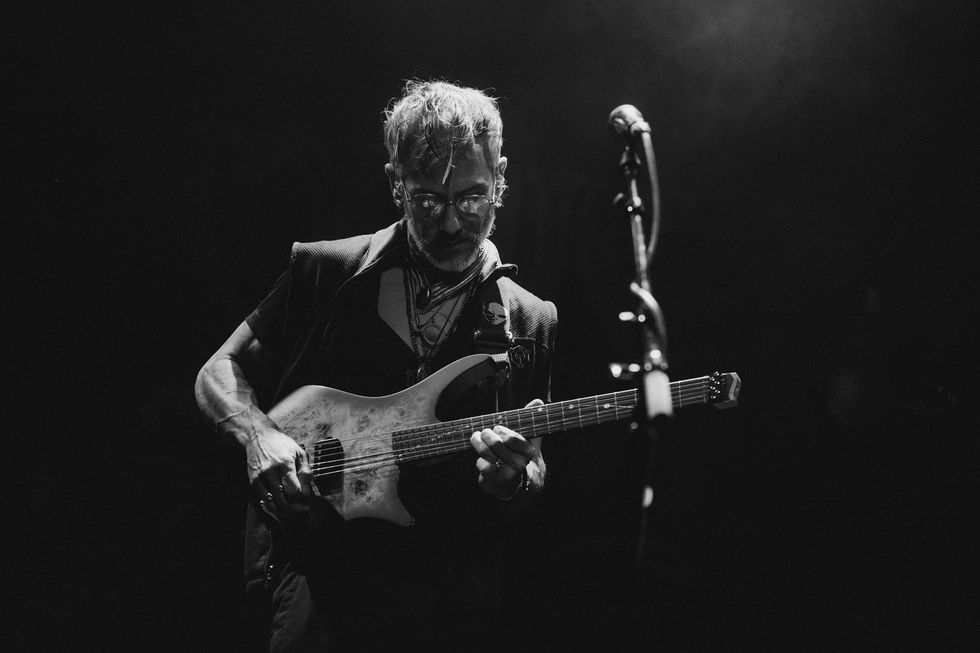

Paul Masvidal wields his signature Strandberg Boden Masvidalien NX 6 Cosmo live with technical death metal pioneers Cynic.

Photo by Stephanie Cabral

It was clear to Ned that if this bass design was going to succeed, he would have to build them himself. And that’s just what he did, creating his namesake brand and heading to the 1980 NAMM show. There, displayed alongside countless basses from Fender, Yamaha, and even Spector, would be his headless, paddle-shaped, carbon fiber Steinberger L2 bass.

“We had a little 10' x 10' booth,” Ned remembered. “Most people walked by and looked at us like we were crazy. But NAMM put on a huge concert that Saturday night, and the [Dixie] Dregs came out, with [bassist] Andy West. And unbeknownst to me, there he was with a Steinberger bass! That was the beginning of everything. We were nothing until an artist took it out there and said, ‘This is cool.’ Then, the day after, you had to stand in line to get into our booth.”

Everything had changed. Soon, Steinberger basses were shipping around the world. Headless electric guitars were no longer an experiment by a curious furniture designer. They were a legitimate take on electric guitar design, and it was only a short time before Steinbergers were in the hands of some very influential players.

Sweetwater Senior Category Manager for Guitars Jay Piccirillo remembers when he first encountered the brand. “To me, Steinberger was [Rush’s] Geddy Lee,” he says. “I wanted one so bad, just because he played one. That was probably the Power Windows era, and his bass tone was so cool.”

Allan Holdsworth played headless guitars since their early days, and he’s had several headless signature models dating back to the Steinberger GL2TA-AH all the way up to this modern-day Kiesel.

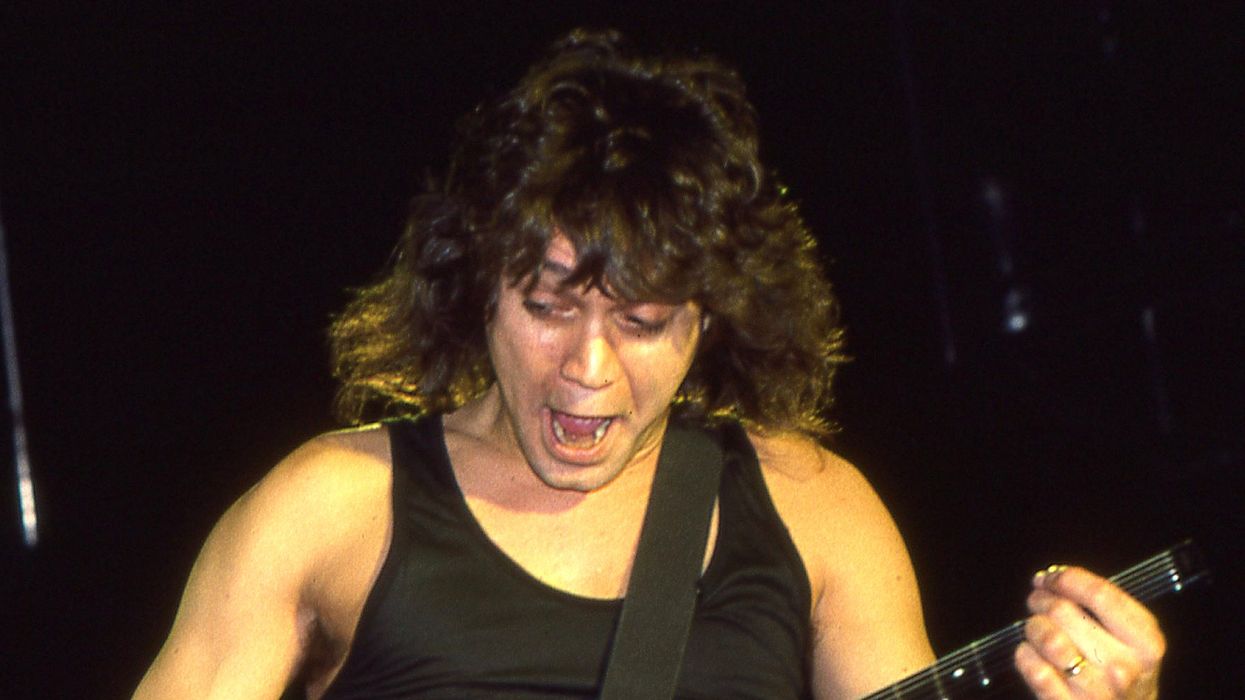

Steinberger guitars followed in 1982 and were adopted by everyone from Allan Holdsworth and Genesis’s Mike Rutherford to forward-thinking side-musicians like Reeves Gabrels (David Bowie, Tin Machine, and, now, the Cure) and David Rhodes (Peter Gabriel). Even Eddie Van Halen got into the act, composing “Summer Nights” around Steinberger’s revolutionary TransTrem system.

In 1987, the big guitar builders finally came calling, allowing Ned to sell Steinberger to Gibson. Unfortunately, as the 1990s drew closer, so did a seismic shift in popular culture. Though still going under Gibson’s leadership today, Steinberger would, in many ways, be a casualty of the decade.

The Decade That Changed Everything

By the time 1992 rolled around, bands like Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Sonic Youth had replaced the technology-tinged tones of the 1980s. It was as much a reaction to the previous decade’s fashion and trends as it was a trend of its own. Anything related to that era’s guitar playing, including Steinberger, was gone. Even the early Steinberger stalwarts had turned their back on their beloved L2s.

“Sting [who famously used his L2 on the Police’s Synchronicity album and on the Ghost in the Machine tour] is an interesting story,” sighs Ned. “He played a Steinberger for a few years. Now, he’s done a complete 180, and he’s playing an old Fender. Geddy Lee, too. While there are still all these people out there that really appreciate Steinberger instruments, not everybody has stayed with it.”

Piccirillo thinks he knows why. “I think the timeliness—and not the timelessness—of some of that music, that’s maybe where it started to fade. I think of a Kevin Shirley interview I read while he was producing some of the later Rush albums. He told Geddy, ‘Get away from the modern stuff. Go grab your Jazz Bass, and let’s crank up that old SVT.’”

Whether it was changing fashion or preference for tone, by the 1990s, Gibson was sitting on a game-changing brand that had made next-level instruments for some of the most popular and finest musicians, and nobody wanted them. Well, nearly nobody.

Headless Goes Underground

While the rest of the world focused on Seattle, the band Death, featuring guitarist Paul Masvidal, also a member of Cynic, had emerged as a leader in the Florida death metal community. In 1991, Death released Human, which many consider the first technical death metal and progressive death metal record, and Cynic’s Focus followed in 1993. Both albums laid the groundwork for modern artists as diverse as Plini, Animals as Leaders, and Per Nilsson. And like many of them today, Masvidal made his music on headless guitars—the Steinberger GM and GR models.

Strandberg’s Paul Masvidal signature, the Boden Masvidalien NX 6 Cosmo, strikes a pose.

Photo courtesy of Strandberg Guitars

“When I played on Death’s Human, Steinbergers weren’t popular,” Masvidal remembers. “But I had no issues with [there being] no headstock. To me, it was groundbreaking. Those guitars felt alien, and I felt like an alien. It was also when my playing started to go into new places. My harmonic vocabulary and soloing style expanded. I started to feel like I was onto something, and that was somehow in tandem with this instrument. With Focus, a voice was emerging, and the headless guitar was the beginning of that for me.” Photo courtesy of Strandberg Guitars

Masvidal wasn’t alone. A small but passionate network of collectors also kept the headless-guitar design alive. Two of which were Headless USA’s Donald Greenwald and Jeff Babicz (also of Babicz Guitars). Calling themselves the “home of everything headless in the music world,” their company was ground zero for buying and selling classic, U.S.-made Steinbergers, accessing hard-to-find headless hardware and strings, restorations, and anything one might need on a headless guitar journey.

“Those guitars felt alien, and I felt like an alien.” —Paul Masvidal

Greenwald unfortunately passed away in late 2022, but he left his partnership in Headless USA to his dear friend and guitar confidant, Natalie Thayer. Still teamed with Babicz (who worked in the original Steinberger factory), Thayer’s goal is to honor her friend’s legacy by playing a major role in the current popularity of headless guitars.

Ola Strandberg

Beyond Masvidal, Greenwald, and Babicz, several online guitar builders’ groups and forums were dedicated to the headless guitars, covering every topic from vintage headless gems to creating new designs. Little did they know, hiding in their ranks was a soon-to-be electric guitar icon, Ola Strandberg.

In the 2000s, Ola was a hobbyist guitar player looking for a way to unwind from his stressful life. A tinkerer since birth, he says that he soon found himself thinking of an old Steinberger copy he had torn apart years prior. “It was a Hohner with the Steinberger-licensed tremolo system,” he recalls. “The hardware really appealed to me from a technical perspective. It was next-level stuff compared to traditional hardware. So, I ended up tearing it apart and building a different guitar around the hardware.

“Then, I got back into guitars in 2007 as a mental recovery after a pretty intense period of work, and I wanted to build another guitar. The headless concept … I couldn’t see myself doing anything else. It just made sense for so many reasons.”

Direct from the “cutting edge” of headless designs, according to Sweetwater Senior Category Manager for Guitars Jay Piccirillo. Ibanez has several forward-thinking models, including this EHB1005F Fretless 5-string bass.

Ola wasn’t out to make a Steinberger clone. Like Ned, he wanted to take what existed and make it better. The difference was that Ola says he “wanted to build a guitar that had some references to what a traditional guitar would look like and that would appeal to what I would want to play.”

From custom hardware to a new body shape, nothing was off the table. Refusing to compromise, the guitar Ola arrived at—now called the Strandberg Boden—was an instant winner and caught the attention of another of the forum’s members. As Ola explains, this part-time luthier and full-time musician was at the epicenter of a new style of highly technical, heavy new music and was about to change his life forever:

“Chris Letchford of Scale the Summit came up to me and said, ‘I hang around the forum because I’m a guitar builder, but my music is taking off, and I don’t have time to build guitars. Can you build me a 7-string guitar?’ I hardly knew 7-string guitars existed, but I said yes. So, guitar number five was for Chris.”

Letchford was hitting the road on package tours that included four or five bands, sometimes sharing members and gear, Strandberg recalls. “Chris showed it to Tosin (Abasi from Animals as Leaders) and Misha (Mansoor from Periphery), and I built number eight for Tosin and number 15, I think, for Misha.

“They were producing a new type of music, and it was perfect for them to have a guitar that looked different. They were a lower weight, had quicker response, and had better resonance. They addressed a lot of the issues they were having with traditional extended-range guitars. And, obviously, with those guys out there playing to audiences largely composed of other musicians, it was the perfect viral marketing.”

“The headless concept … I couldn’t see myself doing anything else.” —Ola Strandberg

Like Steinberger in the ’80s, the orders started flooding in. Strandberg had set off a headless-guitar tidal wave that’s still going strong. What once shocked the industry is now found next to Les Pauls, Strats, and dreadnoughts. For devotees of the design, it’s been a long time coming— especially for Ned Steinberger.

“Think about this,” Steinberger says. “It was less than 30 years from when the Fender bass and Strat were introduced to when I got started. It is now 50 years later. That blows my mind when I think about it.”

Ned Steinberger’s latest design project, the Phin, built by Patrick Sankuer of Sankuer Composites Technology using carbon fiber. The self-clamping bridge tuners are 3D printed in bronze-infused steel, and the custom EMG pickup incorporates 3 humbuckers inside a single housing.

Is the Future Headless?

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, the decades of hard work have paid off. Countless guitar brands like Ibanez, Traveler Guitars, and Kiesel have now put their take on the headless thing. These companies are pushing their own boundaries in design, and the headless community is happy to have them. But is there enough demand to keep all of these builders afloat? Piccirillo says yes: “Ibanez, as far as the bigger manufacturers go, they’re the cutting edge. They spend a lot of time with artists and developing the next iteration to make things better and better. And Strandberg already broke through. They perform consistently, they have wide distribution with lots of great retail partners, and they have enough artists that legitimize the design in the eyes of others. Demand is still huge, and it’s not slowing down. There’s plenty of room for brands to join in.”

“It was less than 30 years from when the Fender bass and Strat were introduced to when I got started. It is now 50 years later. That blows my mind when I think about it.” —Ned Steinberger

“I don't think there’s any going back now,” says Masvidal. “The post-Cynic artists that are creating these sounds need them, and there are so many. It’s post-trend now. It’s still there, and it’s still holding up. There are so many companies that are making interesting things and pushing the envelope. They’re not going to turn that uncool corner again. It’s just not going to happen.”

The very soul of headless electric guitar design is the unwavering charge toward progress and evolution. From the work Ned’s doing today with his company NS Design to Strandberg’s line, to Ibanez or Kiesel’s creations, the platform, by its nature, must move forward. That takes commitment from builders, players, and retailers. Luckily, it’s in good hands.

“I’ve had a lot of heart-to-hearts with Ned and Don about the future of the headless guitar business,” says Thayer. “I want to put some fresh, grassroots effort into revitalizing it. This headless resurgence is the perfect opportunity. I think it’s going to be like the Les Paul and the Strat. I see a huge future for [headless] guitars, and I think it’s only just begun.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)