Reeves Gabrels is the Ricky Jay of guitar: smart, fast, funny, and supremely good at his game—really, at all the games requiring 6-string sleight of hand. Gabrels might begin a song—like “Yesterday’s Gone,” on his 2017 Imaginary Friends Live—with cascading, cumulus, whammy-tugged chords that set an air of mystery, but as the music unfolds there are no boundaries. When that ballad concludes 14 minutes later, it’s been refracted through a prism of metal, fusion, Hendrixian wailing, and pure textural improvisation to dissolve in diffuse tailings of dissonance.

That’s no secret to those who’ve watched Gabrels’ career since 1988, when he was elevated onto the international stage in Tin Machine and began a 13-year creative partnership with David Bowie. During that spell, Bowie and Gabrels cowrote more than 70 songs and made eight albums, including their coproduction Earthling, which stood as Bowie’s most creative recording since his so-called Berlin trilogy—at least until his finale, Black Star. That’s also no secret to those who caught Gabrels in Life on Earth, the Dark, the Atom Said, Modern Farmer, or the other bands he played in on Boston’s club scene during the ’80s and ’90s—although even many of his earliest fans would be surprised to learn that one of his best-paying gigs in the pre-Bowie years was playing country music in suburban honky tonks with Jackie Lee Williams. (And yes, they have honky tonks in Massachusetts.)

After parting with Bowie, Gabrels settled in Los Angeles for a spell. He played some high-profile sessions for albums by the Stones and others, but what Gabrels was really doing was developing his muscles as a solo artist. Starting in 1995 with The Sacred Squall of Now, he’s made six albums that showcase his singing and songcraft, as well as his guitar. His current band is a feral power trio, based in his adopted American home of Nashville, called Reeves Gabrels & His Imaginary Friends.

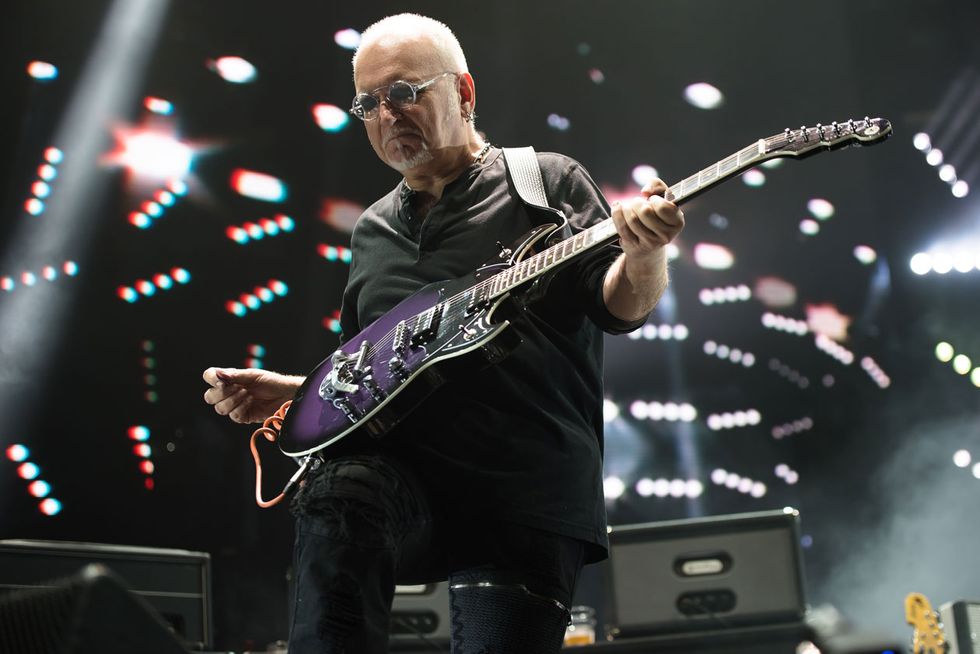

His other current band is the Cure, so Gabrels spends much of his time in London. He’s done that since 2012, when his actual friend Robert Smith invited him as a guest for a string of summer festival gigs with the Cure. Gabrels had played on the Cure’s 1997 single “Wrong Number” and a cut the band contributed to The X Files movie the next year. Turns out those gigs six years ago were actually an audition, and Gabrels has been a member of the band since. When the Cure’s not on tour playing fests like Coachella and Reading, they’re working on a new album.

Recently, Gabrels also worked on a new old album. Per Bowie’s posthumous request, Gabrels and a cast that included guitarist David Torn, bassist Tim Lefebvre, drummer Sterling Campbell, and producer/engineer Mario McNulty convened in New York City’s Hendrix-built Electric Lady Studios to re-record and reimagine an album Bowie felt had missed its mark: his 1987 Never Let Me Down. The project was part of a master plan Bowie left for managing his legacy, and the result is a much more organic and toothy take on that album’s 11 songs.

Speaking about the original version in Interview magazine in 1995, Bowie observed, “I felt dissatisfied with everything I was doing, and eventually it started showing in my work. Let’s Dance was an excellent album in a certain genre, but the next two albums after that showed that my lack of interest in my own work was really becoming transparent. My nadir was Never Let Me Down. It was such an awful album.”

Now, it is not. The drum machines, keyboard-fat mix, and era-dominating studio signatures like heavily gated reverb have been stripped away to reveal the heart of numbers like “Day-In Day-Out” and “Time Will Crawl,” baring the album’s balance of romance and apocalyptic dread. “New York’s in Love” now carries all the frenetic impact of the city, with Gabrels spray-painting the walls of the song. “Zeroes,” which has been released as a single, recalls the balladic strength of Bowie’s Ziggy era, and “Glass Spider” is chilling ambient poetry. All of this can be heard right alongside the original version of Never Let Me Down in David Bowie: Loving the Alien (1983–1988), the fourth in a series of box sets released so far that will altogether span Bowie’s career from 1969 until the end.

When we spoke to Gabrels, by phone and at Roger Alan Nichols’ Bell Tone studio in Nashville, he was in a creative hotspot: fresh from the Bowie sessions, cutting more tracks with the Imaginary Friends, and preparing to return to London for more work with the Cure. To begin, we talked about his three musical heads.

You have your own trio, the Cure, and, now, this Bowie project. What concentrations in your playing come to the fore in each?

With my trio, because I’m singing as well, I try to be responsible to the singer and provide the appropriate chords so he can sing the melody. And then when there’s an open space, I’m kind of wishing I was Coltrane. I like that we’ll do group improvisations where we don’t know how long it’s gonna be or we don’t know where we’re going, or there are ambient interludes, and you can hear that on the live album that came out last year.

—Reeves Gabrels

Next is the Cure. I’ve known Robert since ’97, and he’s been on one of my records, so he knew what I play like. I seemed like a logical choice to join the Cure in 2012 to some people, and to others I seemed like a strange choice. That’s another case where I’m there to support the singer, so it’s not about putting your foot on the monitor and pushing it out. I had a lot of songs to learn with the Cure. They are incredibly durable, really good, well-structured songs, so you could actually take the approach of treating them like jazz standards. [Chuckles.]

And we’re owning our age—the stature of the band. Before the Cure happened, and therefore before the whole Goth bag happened, you were just a Lou Reed fan if you wore black, and before that, you were a beatnik, you know? So it’s really a band that has created a whole genre. I’ve become a more responsible guitar player for being in the band. I know the song, I play the song, but there are subtle variations that I can do that are reactive to Robert’s things, or to the audience, or to the rest of the band. And then a quarter of the night, I’m off the leash.

Well, you know what Hunter Thompson said: “When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.”

With David, at the end of the set, my job was to be the guy that went for the extra points. We’re already winning the game, but here, let’s give Reeves the ball and see what happens. And really, even with David, I figured out that in a two-hour set, the average fan could only take maybe two or three doses of the full me before I overstayed my welcome.

The only thing David ever asked me to do was turn up and not play the solos so much like the record. A couple of gigs in, on the first Tin Machine tour, he said, “I hear you kinda sticking to the solos from the record.” I was trying to keep the band glued together, because Tin Machine could blow apart at any point. And he was like, “Well, don’t do that.” [Laughs.]

The Cure is a different beast than anything I’ve ever been a part of, and playing those songs is a nice musical experience. If you’re a guitarist, you think about guitar playing, but if you’re a musician, you’re thinking about the music. I hate to think it, but maybe I’ve matured.

Gabrels’ custom-built Audio Kitchen amps, Thing One and Thing Two, stand behind him at a Cure show. “For the Cure’s stuff, I need loud and clean, and my stage volume sits right around 100 dB, but I need to be able to boost it 5 dB without it compressing,” he says. Photo by Mauro Melis

And now you’ve revisited your time with David, in a sense, during the sessions for the new Never Let Me Down.

David and I talked about those songs a lot through the years, and so I kinda knew what he liked and what he didn’t like. I purposely didn’t listen to them before I went in the studio. I wanted to treat the original versions like they were demos, but I didn’t want to have parts stuck in my head. That was the kind of scenario David encouraged. A lot of people think David dictated every note, but David was like an art director. He assembled people whose work he liked and saw what happened, then edited from there.

Did David leave instructions for the project?

Bill Zysblat, who’s running the Bowie trust, kind of explained that David left a five-year plan. So, at the beginning of a year, they just tear open an envelope and see what the instructions are. As I understood it, he left a list of musicians for the project. I was a sounding board, perhaps, for Mario in the process. It was nice for me just to be the guitar player, because I spent a lot of years where I was worrying about way more things than just playing guitar—writing those pesky songs with David.

The recording process was fairly organic. Mario and David’s plan was to keep David’s vocal, keep his guitars, and replace the drum machine with real drums, and build it up from there. So Mario got Tim Lefebvre and Sterling Campbell, and they went in, and they spent about a week just doing bass and drums against David’s guitar or a keyboard pad that defined the harmony, and David’s vocals. We had talked about maybe me recording with the rhythm section, but I was out with the Imaginary Friends in Texas at that point. So I couldn’t do it.

With “Time Will Crawl,” they had kind of established a sound. When I came in, I spent a couple of days doing some guitars, and then David Torn came in for a day while we were at Electric Lady, so there were a couple tracks—“Shining Star” and “Glass Spider”—where we played simultaneously, which was fun.

Did you already know David Torn?

We had spoken via email and on the phone, but we had never met. You would think the overlap between the two of us would have made it unnecessary to have both of us. But like it often happens, when you put two things next to each other, you see the differences. Torn, with his ambient and atmospheric stuff—there’s something really gentle about his playing, and intimate. I’m more of a bull in a china shop, so that difference became apparent from early on.

What was revisiting your time with David in such a visceral way like, emotionally?

Hearing David’s voice on the multitrack ... when Mario and I were getting ready to record, we listened to “Zeroes,” and we kinda looked at each other, and were, like, “Wow, this should be a single!” Jokingly—but apparently now it is. We realized it needed another acoustic guitar. So I figured, “I’ll do this first. It will be a good way to get into it.”

So they set me up to record an acoustic guitar in the live room: Studio A at Electric Lady. It’s the Hendrix Room, so there’s all this vibey stuff going on in there. I had my headphones on. I had me in my right ear and David’s guitar in my left ear—and the vocal in the middle, bass and drums.

David and I always used to record, from Tin Machine times on, the acoustic guitars simultaneously, facing each other. And he tended to emphasize his downbeats, like one and three, and I tend to sit on the backbeat. So we had this nice push-pull-in-stereo feel, panning left and right. And he would also get this look in his eyes while we were tracking: He was looking at you, but he was also looking miles away. He would cross his leg and his foot would bounce while he was playing.

So, I have all these memories of that, and while I was playing, I had my eyes closed, and I’m hearing him in my left ear, his guitar, hearing his vocal in the center. I can feel him hitting the one and three a little bit harder, and me hitting two and four, and I can see him in my mind, sitting across from me the whole time.

Then we get to the end of the song, and I opened my eyes … and he wasn’t there. I was glad I was in the room by myself because—it’s even hard for me to recount it now—it brought a tear to my eye. And so there was that.

And the other thing about the group of musicians was that we all wanted to see David happy, you know, with what we were doing, and we all cared about him. We all loved him, basically. So it was a labor of love for everyone involved.

We just wanted to serve the songs, really. The original version—everybody played great on. And if you like the original version, the original version’s being remastered and it is being released as well, so it’s not like we’ve erased history. But David always said that he felt the songs were great, but he kind of “checked out” during the recording. So it’s been an album that’s almost more about production—that 1985–’87 sound. We stripped the songs back quite a bit, and you can hear them now as the songs that they are.

Are there places on the album where you really uncorked?

Yeah, a bunch of them. [Laughs.] On “New York’s in Love” ... I like to cut what would be considered the lead guitar first and then go back and respond to that track with other guitars later. If the song is a room, it lets me into the room, and I’m lifting up the couch pillows and looking for change, and checking out what’s fastened to the wall and moving the furniture around.

Parenthetically, on “New York’s in Love,” Peter Frampton had played rhythm guitar, and we kept the guitar parts from the original, and kept Peter’s sitar on “Zeroes,” and we kept Carlos’ [Alomar] gated rhythm on “Never Let Me Down.” And then pretty much everything else got replaced.

But anyway, on “New York’s in Love,” I was thinking about how much New York had changed since 1987, and like what you hear walking around on Saturday night. There’s definitely more of a cultural melting pot—more Middle Eastern and Asian influence now. On the original version, it was Peter’ blues-rock-influenced soloing. I decided to substitute more microtonal modal stuff. I did it in one take, first take—I just went for it, and when I got to the end, Mario just looks at me, and he goes, “Well, I guess that’s done.” “Beat of Your Drum” has moments of that, too. “Zeroes”—I freely played and took a couple of runs at it, and we figured out we had what we were looking for. “Zeroes” still has that freedom to it.

It has more of a textural vibe.

Yeah, a melodically relaxed thing. It’s not as fraught as, say, “New York’s in Love,” where I was thinking of the sirens you hear on Saturday night and people trying to sell you something on the street. “Buy a watch!” “Zeroes” was an emotional response to the lyrics and to what I felt when I was recording the acoustic. And in “Bang Bang,” I was feeling sort of a fractured blues thing, so I used a Trussart Telecaster and a Fender Bassman with a GE-7 Boss Graphic in front of it to spike certain frequencies.

Since you mentioned the Yamaha modeling amp, what gear did you use for the sessions?

I used, basically, the same as my usual live rig with the Imaginary Friends. I found an old Ibanez Weeping Demon wah that I brought with me. Also, a Varidrive tube distortion, a Source Audio Multiwave distortion, a GE-7 graphic fuzz modified by the Thru-Tone guys in Nashville, a Phase 90, an M9 with an expression pedal, and an Ottobit Jr. bit crusher/randomizer thing that I actually bought on the second day of the session and ended up using on “Beat of Your Drum.” It has a randomized setting that you can tap a tempo into, and it will do something very similar to what the old H4000 Eventide unit did, which is periodically grab a note and just spin it, delay it, cut it up, jump an octave … you don’t know what it will do next. But I like that.

We did a couple of passes on the solo. I started way far out and then dialed it back, and I think we mostly used the dialed-back one, where I just used Ottobit Jr. at the end of phrases, so that last note would get hurled off into the depths of space. Then that went in stereo out of the M-9, into the front end of the THR100, which I had running as two separate amps: one sounding like a Hiwatt with a 5881 in the power-amp section, and the other sounding like a Deluxe with 6L6s, with two of the Yamaha THRC speaker cabinets. They had different Eminence speakers—a Tonker and a Cannabis Rex, I think, but we tended to like the one that was getting fed the Hiwatt-sounding side of the Yamaha. That might have been the Tonker, because that’s kind of more like a Celestion.

The other thing about the amps is, we used the room at Electric Lady, because it would be a crime not to. We had ambient mics up. And that was the rig for everything except some of the stuff I did at Mario’s studio, where I used a Line 6 Helix and my pedalboard.

Gabrels cradles one of his signature models, the Reverend Spacehawk, in Nashville’s Bell Tone studio, where he’s at work on new recordings with his own trio, Reeves Gabrels & His Imaginary Friends. Photo by Andy Ellis

And were you using your signature Reverend electrics?

The guitars were my RG1, but with a sustainer in it, and the Reverend Spacehawk, my other signature model, with just a stop tailpiece, and a Trussart SteelCaster with a humbucker PAF-ish-style pickup in the neck. And then, right at the last session, I bought a Les Paul R7 goldtop. I thought we were done, and I get a phone call from Mario, and he goes, “There’s one more guitar part.” So I went over to his house with the Les Paul, and I ended up using the Les Paul and the Spacehawk on the intro, and it gets repeated at the verse intro, on “Beat of Your Drum.” And the acoustic was a Breedlove.

Do you have .009s on your electrics?

I’m running .009 to .046, and I’m using D’Addario NYXLs. I’ve never liked the multi-colored ball ends, because when I look down it looks like Playskool [laughs]—like I should be playing a toy xylophone, so they make the ball ends black.

Very stylish. [Laughter.]

I would have settled for brass. I didn’t expressly ask for black, but they ended up making them black for me, so….

How different is your rig for the Cure?

Well, my pedalboard is pretty big! [Laughs.] But I use some Peavey stuff, as well as the Line 6 Helix. I also use my signature Pro Tone Distortion Engine and their dual distortion pedal with the Cure. Amp-wise, my friend Steve Crow owns Audio Kitchen. I’ve known him since he was a guitar tech in London, when he was, like, 17. I said to him a long time ago that I really liked the Baxandall front end, from the old Ampex recorder, but I like the class A sound.

I like the way an AC30 sounds before it starts to overly compress, so it’s rich sounding but it’s not distorted. But I’d like that sound a lot louder, so I said to him jokingly, “Could you make an amp with a Baxandall front end that has a class A power amp section that doesn’t start to squash out and distort and is maybe four times as loud as an AC30?” So he laughed at me, and he told me all the reasons why it wouldn’t work—just in terms of the size, the amount of iron, the size of the transformer. It would have to be the size of the SVT, and it would take two people to lift, blah blah blah. And then about three months later I get a schematic from him, and basically it was the amp I was talking about, but because it’s class A, you don’t have to have pairs or quartets of power tubes, so it had three KT88s in the power amp section and it was rated at 50 watts.

I compared the prototype to my 100-watt Hiwatt, which I had been using with the Cure, and it was louder than the Hiwatt and a little bit cleaner. For the Cure’s stuff, I need loud and clean, and my stage volume sits right around 100 dB, but I need to be able to boost it 5 dB without it compressing. He built, as far as I know, only two. It looks like a big box with a little hole in the center of it. It’s really comical. They’re called Thing One and Thing Two. And that’s what I use in the Cure. And I use a 100-watt Hiwatt head for my Bass VI.

Returning to the past, how do you reflect on the years you spent with David Bowie?

He opened the door for me. If it wasn’t for him, I probably would have never gotten out of Boston. And it was always funny to me that after I started working with David, a lot of people that I had wanted to work with all along, but wouldn’t give me the time of day, suddenly were having me because I had the David Bowie Good Housekeeping Seal of approval.

In the early days, David had a very … older brother thing with me. The music thing was the easy part. I understood that. And even hostile press: The bands I had in Boston were never anybody’s darling. And I realized pretty quickly that international press is no different. So that was easy. But David said to me early on when we were in the studio, during what became Tin Machine but before the Sales brothers were involved, “It’s great when we’re behind these walls, but as soon as we get out in the world and start dealing with the paparazzi side of press and things like that, it’s gonna get weird. It’s like, basically, we’re all equals in here, but as soon as we get outside, it’s gonna be all about me.” And he said, “The only thing that any of this stuff is good for is I can get a good table in a restaurant so I’m not near the kitchen. And I can get free tickets to shows.” [Laughs.]

We were literally using Mountain Studio in Switzerland as our demo studio for what became Tin Machine. And that was a lesson. We got in an 10 a.m., then we were sitting around for two or three hours, having breakfast, reading the papers, talking about stuff, basically shooting the shit, and the clock’s ticking, man, you know, what the fuck? But what I learned from him is the worth of reading the paper and talking: Eventually someone would pick up a guitar or a keyboard and play something, and one of us would go, “Hey, that’s a good idea.”

The point was, everything informs the process. Or the process informs the art. And part of the process is the hang. And once the ball starts rolling, you might work three times as fast as somebody else in the studio, because another thing I learned with David is to always be ready to record. Always. So, if you started at 10, you might not get as much done by 5 o’clock as we did when we started at 2.

I learned from him to treat the studio like I treated my Tascam Porta One, where I learned to bounce, like, 11 guitar tracks. So that allowed for all kinds of creative experiments that you wouldn’t normally do. The crux of that is having money to pay for the time. Now everybody has Pro Tools.

Another thing I learned is that you don’t judge an idea until it’s brought to fruition. It’s like trying to start a fire with straw and flint outdoors. You all have to crowd around the spark and help it, protect it, so that it catches. And then once it catches, someone gets some kindling, and someone else gets some small sticks of wood, and someone gets some logs, and then eventually you’ve got a fire. Once you’ve got the fire going, it’s okay for someone to say, “Ah, yesterday’s fire was better.” [Laughs.] But until it’s a fire, you don’t judge it. Watching how David worked, I kinda figured out that a lot of dumb ideas turn into brilliant ideas at some point in the process. All you can do is raise them.

Reeves Gabrels plays two solos on his single-pickup Reverend Dirtbike signature model in this performance of “Drown You Out,” shot on tour with his trio in September 2017. The first is pure rock ’n’ roll, while the second is a free-ranging sonic feast that shifts effortlessly from melodic exploration to textural brushstrokes to a cascade of delay-soaked feedback.

Gabrels’ first signature model was the Reverend RG1. This is his favorite example, and one of the main guitars he uses with the Cure. It also was employed on the revamped Never Let Me Down. Photo by Andy Ellis

Reeves Gabrels' Gear

Guitars: Reverend Reeves Gabrels Signature RG1, Reverend Reeves Gabrels Spacehawk, Gibson Les Paul R7, Trussart SteelCaster, and Breedlove Black Magic.Amps: Yamaha THR100H, Audio Kitchen Thing One and Thing Two, Hiwatt 100-watt head, Fender Bassman, and Yamaha THRC cabinets.

Here’s the core pedalboard Gabrels used for the Never Let Me Down sessions: an Ibanez Weeping Demon, Boss TU-3 Chromatic Tuner, SIB Varidrive tube overdrive, Source Audio Multiwave Distortion, Alexander Syntax Error, Meris Ottobit Jr., and Line 6 M9. The signature Reverend Spacehawk was one of his primary guitars. Photos by Peter G. Fisher

Effects: Line 6 Helix, Ibanez Weeping Demon wah, Varidrive tube overdrive, Source Audio Multiwave Distortion, BOSS GE-7 Graphic Equalizer (modded by Thru-Tone), MXR Phase 90, Line 6 M9, Alexander Syntax Error, and Meris Ottobit Jr.

Strings and Picks: D’Addario NYXL (.009–.046), D’Addario EJ26 Phosphor Bronze acoustic (.011–.052), Dunlop Tortex 1.14 mm, and Dunlop T3 .60 mm and 1.3 mm.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)