When you’re chasing music, some nights are special. For me, March 25, 1985, was one of those nights.

The great Les Paul famously held court at Manhattan’s high-profile Iridium nightclub from 1995 until his death in 2009. But before that, he began his return to regular performing at Fat Tuesday’s, a tiny basement jazz room on Third Avenue, in 1984. As soon as I heard about that gig, I had to go.

I was living in Boston at the time, with a day job at a business magazine, and, as luck would have it, my colleagues and I were dispatched to New York City to cover a convention a few months after Les’ Mondays at Fat Tuesday’s started. On the night we arrived, I dragged my fellow suits to the Lower East Side to “come in and hear the truth,” as Les tagged those shows, which blended beautiful music, infantile humor, and silly banter between the elder statesman, then a mere 79, guitarist Wayne Wright, and bassist Gary Mazzaroppi. The audience was sparse, which made the experience rarer and more beautiful, and I left with a head full of melodies, higher than the moon, knowing I had to return.

In March of the next year, I was on yet another biz trip to Manhattan, and this time my wife, Laurie Hoffma, joined me, expressly so we could both see Les. It was cold and slushy outdoors, and the small interior of Fat Tuesday’s was a warm, welcoming retreat—especially when Les’ trio started playing. The setlist was unsurprising. It was music Les had ascended with, during the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s—songs like, to the best of my memory, Gershwin’s “Embraceable You,” “As Time Goes By,” Rodgers & Hart’s “Lover,” “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” and numbers he’d made hits with Mary Ford, like “Tennessee Waltz,” “Vaya Con Dios,” and “How High the Moon.” But regardless of how that looks, these chestnuts didn’t sound corny. They sounded loved. And while Les’ arthritis had already slowed him down, that only made him squeeze everything from each ripened melody and from his lush tone.

“While Les’ arthritis had already slowed him down, that only made him squeeze everything from each ripened melody and from his lush tone.”

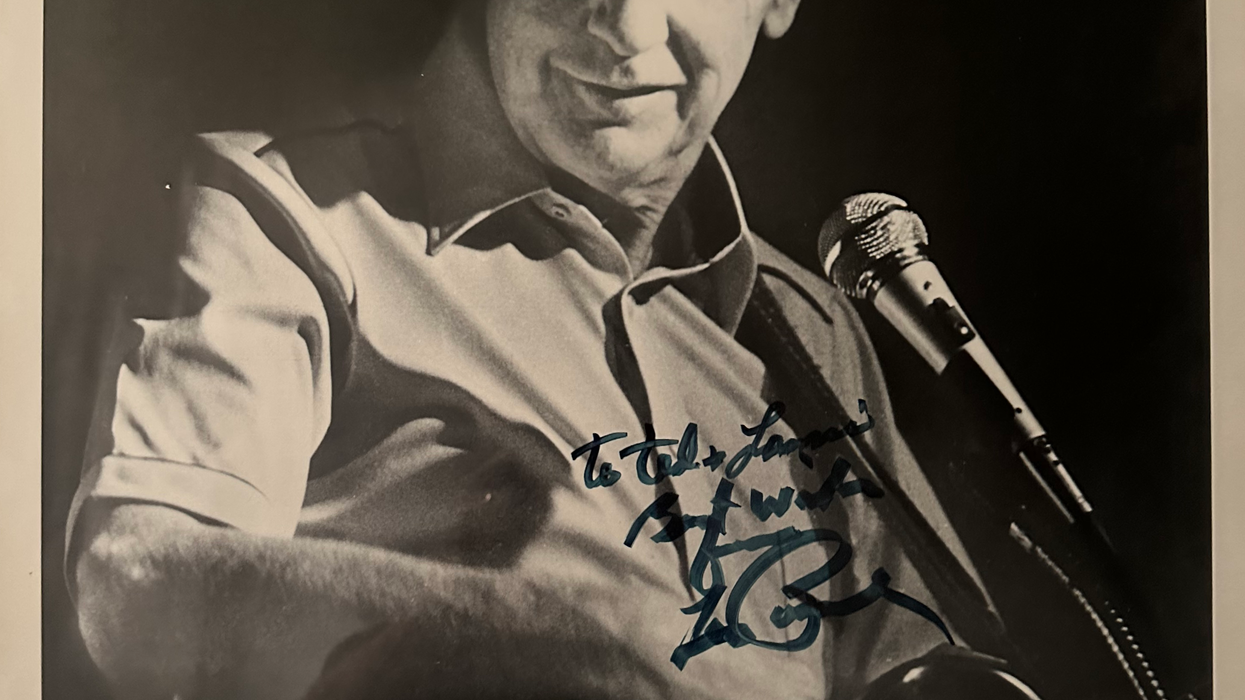

I’d recently begun freelancing for some small music publications and, with Laurie’s urging, decided to introduce myself to Les during the set break and ask if he’d do an interview. This took some courage on my part, because, to me, talking to Les was like talking to one of the heads on Mt. Rushmore. But this 6-string chief of state was exceedingly friendly, walking the club to visit each table, with a drink at the end of his 90-degree-angled right arm, famously fused in that position after a car wreck in 1948 so he could keep playing guitar.

When I got up the gumption to say hi and pitch a phone conversation, Les was pleasantly game and gave me his home number. The club had made posters for the evening, which, as luck had it, was the first anniversary of his Fat Tuesday’s residency. So, he signed one for Laurie and me. But as I turned toward my seat, he stopped me and said, “There’s someone I’d like you to meet. Follow me.” We strolled to a table by the stage where an elderly man with glasses sat alone, and Les told me to take a seat. “Leo,” he said, “this is Ted.” A pause. “Ted, this is Leo Fender.” Mind blown, all I could do was shake his hand, say hello, and sit stunned and still for a moment. I think I mumbled something about admiring his work and nervously returned to our table. I wish I had a second chance at that meeting, but still worry that a barrage of questions would be as obnoxious as the hasty, insecure retreat I made that night. I am now a bolder person, largely thanks to decades of interviews and fronting bands.

That first interview with Les was magical, if unconventional. I asked him about his start in the music business, and his answer was nearly an hour long, as he giddily, almost breathlessly, recounted his path from playing guitar at a drive-in restaurant as a “freckle-faced, red-headed kid” who “attacked the guitar,” to fibbing his way to his big break with Fred Waring and his Pennsylvanians, with nods to clarinet player Stinky Davis and jazz legend Miles Davis, and on to a new guitar he was designing but couldn’t speak about until he got the patent. And then, he had to go. His non-stop answer, nearly verbatim, became my entire article. And every time I think of that night at Fat Tuesday’s, it reminds me how fortunate my life has been.