Straight from the woozy opening rip of “Bedside Manners,” the breakneck lead track from the Black Crowes’ 10th studio album Happiness Bastards, it’s clear that the Southern rockers from Georgia are in as fine a form as they’ve ever been. There are plenty of examples of bands that have lost their sonic teeth or just traded them in for a softer sound. But despite a 15-year gap between the new record and their last long-player, and plenty of time apart, the band sounds just as vital as they did when their 1990 debut, Shake Your Money Maker, first electrified listeners more than three decades ago.

That consistency of their rousing brand of rock ’n’ roll—blessed by rhythm and blues swagger, injected with more than a touch of gospel, and steeped in the traditions of American music—was likely buttressed by the reunion tour they set out on to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Shake Your Money Maker in 2021. And, by the fact that at least three of the members—Rich, his brother and lead singer Chris, who co-founded the band, and bassist Sven Pipien—all came up together in Atlanta. It could, above all, come from their pure desire to never stop making music.

The Black Crowes - "Wanting And Waiting"

But at least one of the primary driving forces behind the band’s vitality is Rich Robinson’s guitar playing—distinctive but also familiar in the last 30-plus years of rock; always nuanced and natural, frequently stirring, and just as compelling in blistering electric riffs as it is in delicate and expressive acoustic arrangements. It’s a palette that Robinson has nurtured since his early teens when he first picked up a guitar, and one of the things, of course, that has tied the Crowes’ sound together throughout their long career. It informs Robinson’s solo albums and his work with the Magpie Salute as well.

“There’s always that common thread,” Robinson says over the phone from Nashville. “There’s always the language. There are certain writers and they choose the phrasing or the pacing of how they write, and their paragraphs and their words. A painter, you know; you’ll see people who have a signature to the way they paint. That’s why we love them. In movies you see that same thing. So, all creative endeavors have that element in them. Chris sounds like Chris. He’s never gonna not sound like Chris. And I play like me, and I’m never gonna not sound like me.”

“You’ll see people who have a signature to the way they paint. That’s why we love them.”

With his ear first tuned to his dad’s music of choice—Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Sly Stone, Joe Cocker, Bob Dylan—Robinson eventually started sculpting the beginnings of his own sound with his dad’s 1954 Martin D-28 in the early ’80s (Martin’s Rich Robinson Custom Signature Edition D-28 is based on the same guitar). He gravitated especially toward The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and remembers the first time he saw Angus Young being impaled by his Gibson SG on the cover of AC/DC’s If You Want Blood You’ve Got It: “There was something really special about it to me. I was drawn to it.” He and Chris listened to a lot of Prince, and got into punk rock, too—X, the Clash, the Ramones, the Sex Pistols, Black Flag. Next came the alternative stuff, like the dB’s, Rain Parade, and fellow Georgians, R.E.M.

Rich Robinson's Gear

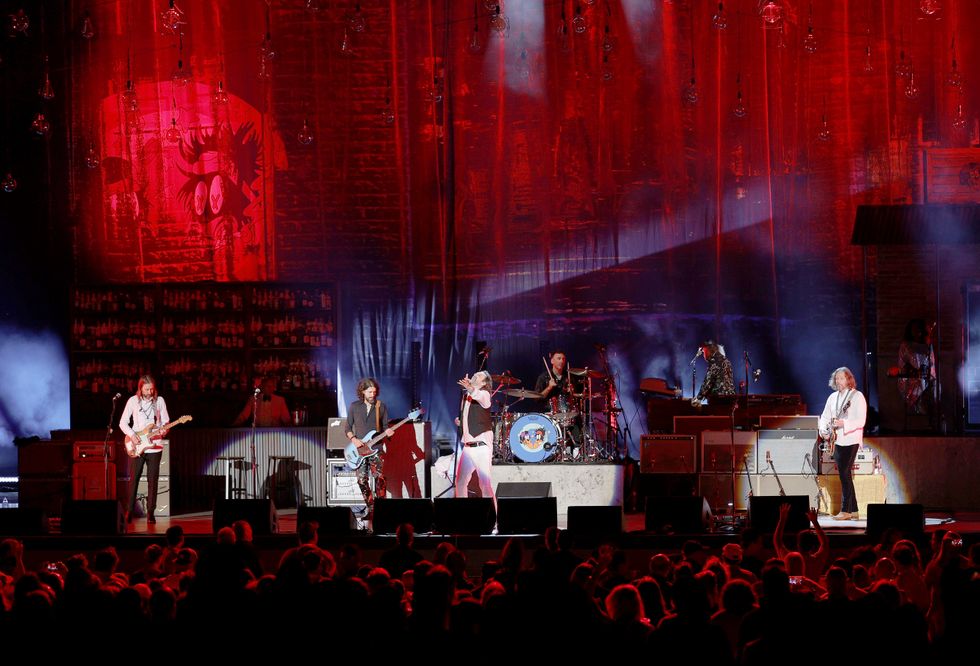

A few years ahead of the release of Happiness Bastards, the band reunited in 2021 to embark on the 30th anniversary of the release of their debut album, Shake Your Money Maker.

Photo by Jason Kempin

Guitars

- 1956 Gibson Les Paul Special

- 1959 Gibson Les Paul Junior TV

- Custom Shop Gibson Les Paul Junior

- Bonneville Les Paul Junior

- Bonneville Strat

- 1968 Les Paul Goldtop

- 1961 Gibson ES-335 Cherry

- 1962 Gibson ES-335 Sunburst

- 1968 Gibson ES-335 Cherry

- 1967 Fender Telecaster

- 2015 Custom Shop Black Fender Telecaster

- Custom Shop Sunburst Fender Telecaster

- Custom Shop Fender Telecaster with B-Bender

- 1999 Custom Shop Mary Kay Strat

- 1964 Rickenbacker

- Stephen Stern Custom White Falcon

- Stephen Stern Custom Magpie

- 1969 Dan Armstrong

- 1972 Dan Armstrong 341

- Zemaitis Disc Front

- Zemaitis jumbo acoustic

- Martin D-28 Appalachian

- Martin 0000

- Martin parlor

- Martin 12-string

- 1967 Guild 12-string

- Piers Crocker Crockenbacker

- Gibson Custom Shop Firebird Pelham Blue

- Gibson Firebird

- Gibson Custom Shop Firebird

- Teye El Dorado

Amps

- 1966 Marshall bluesbreaker

- 1968 Marshall bluesbreaker

- 2023 Muswell 50-watt

- 1987 Marshall Silver Jubilee

- 1956 Fender Deluxe

- 1950s Fender White Model 80

- 1971 Marshall JMP 50-watt

- Handwired Vox AC30s

- 1961 Fender Twin

- 2009 Reason Combo

- 1965 Fender Bassman black-panel

Effects

- RJM MIDI Controller

- Ebo Customs E-verb

- Fulltone Tube Tape Echo

- Fulltone Clyde Deluxe Wah

- Lehle volume pedal

- Way Huge Angry Troll

- Way Huge Red Llama

- Black Volt VFUZZ

- Strymon Lex

- Strymon Flint

- JHS Ruby Red RR Overdrive

Strings, Slides & Picks

- D’Addario strings

- D’Addario Rich Robinson signature slides

- Dunlop picks

“And then it kind of worked its way through us back to our foundation, where we loved roots rock ’n’ roll music,” Robinson says. “But all of that journey shaped how I wrote songs. The first thing I did was write songs. You know, I was never someone who just kind of played all day and learned scales and shredded. I always thought the song was the gift. And that was the thing that was lightning in a bottle, so to speak.”

Robinson was never trying to learn everything about the guitar as fast as he could. He played when he wanted to play, which still remains the case. “And every time I play it, I feel joy, because it’s never laborious or forced,” he says. He cautions against the “apprentice effect”—getting stuck in the lines and grooves of the people you learn from and forgetting to explore the untrodden paths you might be interested in. Through his time playing the guitar, he’s picked up something new here, something new there; his learning process has evolved naturally for him, and continues to do so in the present day.

“I always thought the song was the gift. And that was the thing that was lightning in a bottle, so to speak.”

“I think there’s a time when you peak, and then it just kind of starts going down,” Robinson elaborates. “It’s like you’ve learned everything you can on that instrument. And people play that way. You can kind of tell—it’s almost like people know too much. Every time I learn something new, I think about how I can do that in writing a song, first. I’m like, ‘Oh, man, this is great. I can write this into something.’ But then it also expands how you play and how you see the guitar.”

On Happiness Bastards, the Black Crowes sound as strong as ever, proving they haven’t wavered in their rock vitality since their last release in 2009.

All of the disparate influences, filtered through roots and Southern rock traditions, have helped to build a Black Crowes sound that explores plenty of different sonic territory, but remains singularly theirs. Eventually, the direction in which those sounds went became dictated by the tone of the instrument; the right acoustic guitar, with a certain stunning kind of resonation, can bring hundreds of songs out of Robinson, as can the right guitar with the right amp. The tone, for him, has always been an essential part of the overall mosaic of the song, and if the tone isn’t there, the recording can be a letdown regardless of how great the song is. For example, he says, some of Prince’s records—though the songs and the playing are brilliant—could have benefited from a sound more in line with the unmediated electricity of Sly and the Family Stone albums.

“I just don’t like those tidy, neat, sort of clean things,” Robinson says. “There’s a humanity involved in all of it. There’s a humanity in music, in the sound of the music, and in the composition of the music. And by ‘humanity,’ I mean there are flaws, or perceived flaws, that actually turn out to be the magic. You want to try to get it as good as possible. But you also want to leave that space for a breath, or for anything that shows the human organism that’s growing and breathing and behaving.”

“Every time I learn something new, I think about how I can do that in writing a song, first. But then it also expands how you see the guitar.”

Every guitar, amp, and pickup influences the tone Robinson arrives at, and on Happiness Bastards, he employs many different combinations to get where he’s going. For the punchy and jagged “Cross Your Fingers,” he’s on his 1962 Gibson ES-335 and a Muswell amp; the wiry “Dirty Cold Sun” features a Muswell again, powering a custom shop Tele; a dense Gretsch White Falcon through a ’56 Fender Tweed Deluxe fills out “Flesh Wound”; and “Follow the Moon” showcases his 1956 Gibson Les Paul Special through the same amp.

Rich Robinson, seen here playing his Zemaitis Disc Front back in 2021, owns more guitars than your average collector.

Photo by Frank White

In his search for great tone, Robinson founded Muswell Amplification after building one of his own amps—based on his 1968 Marshall bluesbreaker—with his guitar tech, Roland McKay.

“It’s basically an exact, or almost exact, duplicate of my bluesbreaker,” Robinson says. “It’s a 1968 bluesbreaker I bought that, when I heard it, I was like, ‘Holy shit.’ When you buy one amp that is amazing, you kind of want another one just in case. So I was like, ‘Man, can we do this?’ The guy that I’m building the amps with was like, ‘Yeah, I can get all these transistors, I can get these tubes, I can get everything exact and do this.’ And so we did it. And side by side, it’s incredibly close and sounds amazing.”

Mostly, on Happiness Bastards, Robinson flips between his faithful Muswell and the Tweed Deluxe, pulling the textures of the past and contextualizing them here and now for 21st-century rock ’n’ roll. But perhaps one of the more essential elements of the Crowes’ recording process is making room for the human quirks and dynamics that are more akin to the previous century; Robinson laments the uncanny valley feeling that poorly done autotune affects in him, or the stilted nature of songs played to a click.

“You want to leave space for a breath, or for anything that shows the human organism that’s growing and breathing and behaving.”

“It seems weird to me, because, it’s a natural human response—if a chorus is coming, you’re getting a little excited, you speed up a little bit,” Robinson says about the experience of playing live and loose. “And then after that, you kind of slow it back down. That adds to the dynamic of the song and to the humanity of the song.”

Brothers Chris and Rich Robinson formed the Black Crowes in 1984, while still attending high school.

Photo by Tim Bugbee/tinnitus photography

The building blocks of the Black Crowes’ sound, then, are kindred to those that have helped create any of the great Southern rock bands—a melting pot of diverse influences, close attention to tone and timbre, a motivation that comes from love of the game, and brotherhood. It all seems to make a joyful sound, and could hardly be recreated by putting together all the right technology. Ultimately, the formula can only remain a mystery. “There’s always more to it than something as simple as what an amp might sound like or what a mic or effect might do,” Robinson says.

What makes a compelling guitar player is similarly enigmatic; again, of course, there’s no recipe for a Jimi Hendrix or a Duane Allman. But Robinson says his favorites, the players who he looked to when he was learning—Jimmy Page and Peter Green, for example—all have a few things in common with the other greats: freedom, abandon, and passion.

“I think they’re just unapologetically themselves," Robinson says about what sets the singularly voiced apart from the masses. “They’re not trying to be safe. They’re just doing what they do. They’re artists, you know?”

YouTube It

The Black Crowes rip through the fan favorite “Twice As Hard” during their 2021–’22 Shake Your Money Maker tour.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)