This is our annual DIY issue, where we share a few interesting projects—this time, a guitar mod that's a lesson in the proper way to use a router and six pedal-kit builds—that can be done fairly easily, in one day. The idea is to showcase attainable work that builds basic skills needed for more complex projects.

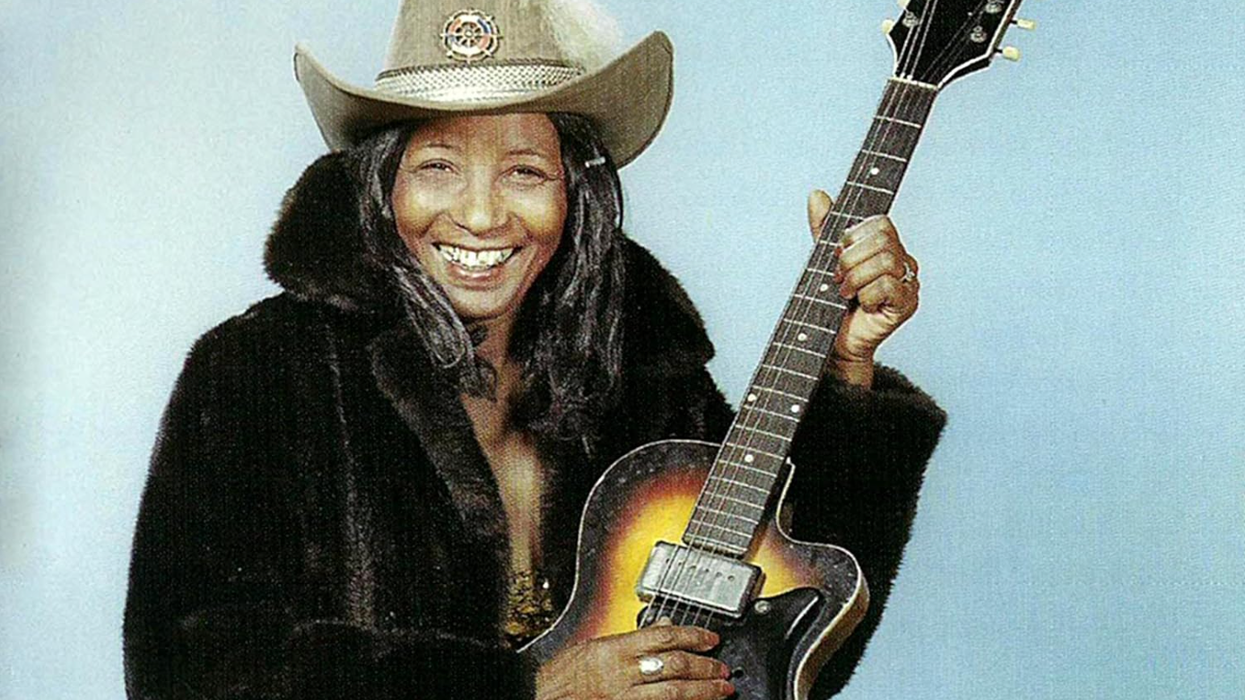

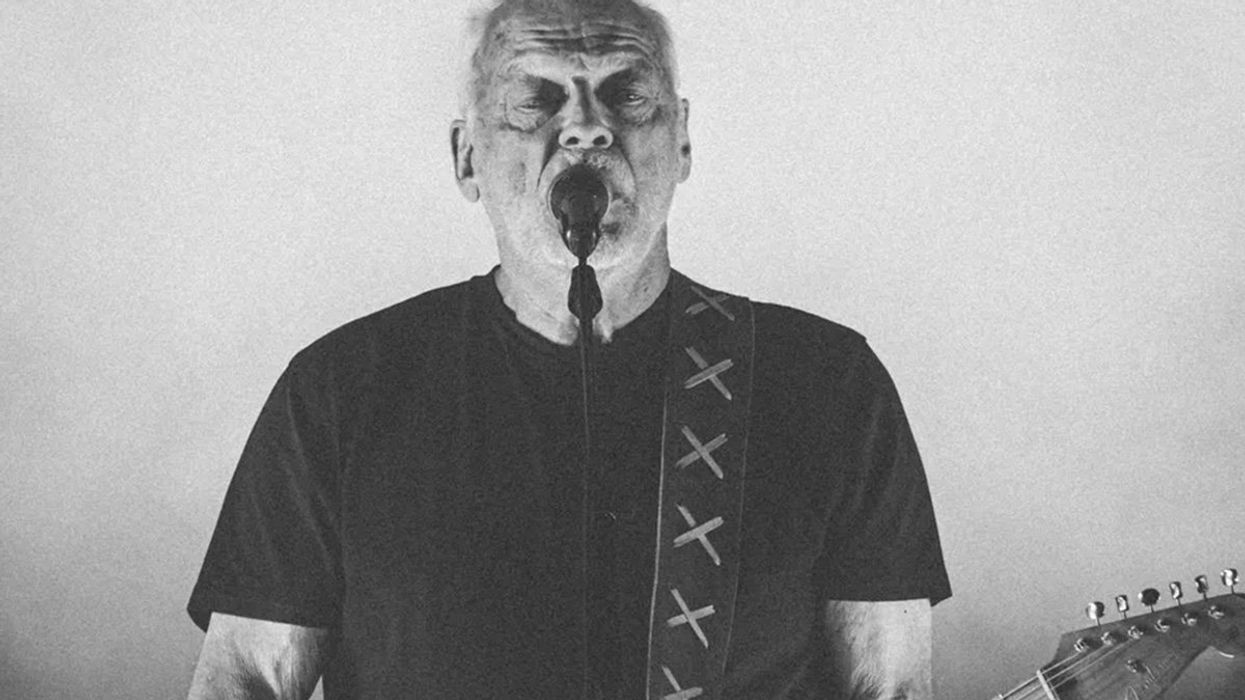

But for those of us with creative ambitions, the most important DIY project is far more complex than a pedal build, a pickup swap, or even homebuilding a guitar. I’ve always believed that the mark of an artist is having a unique character that comes through in their work. There are plenty of examples: Joni Mitchell, James Hetfield, David Gilmour, Polly Jean Harvey, Jimi Hendrix, Ava Mendoza, Anthony Pirog, Hank Williams, Howlin’ Wolf, Yvette Young, Coltrane, Miles, Billy Gibbons, Mike Watt, Brent Mason, and many, many more. What they all have in common is that it takes just a few notes or a vocal line or two to recognize them. Some might only be known in your town, but that doesn't make their work any less viable or important—especially if it’s important to you.

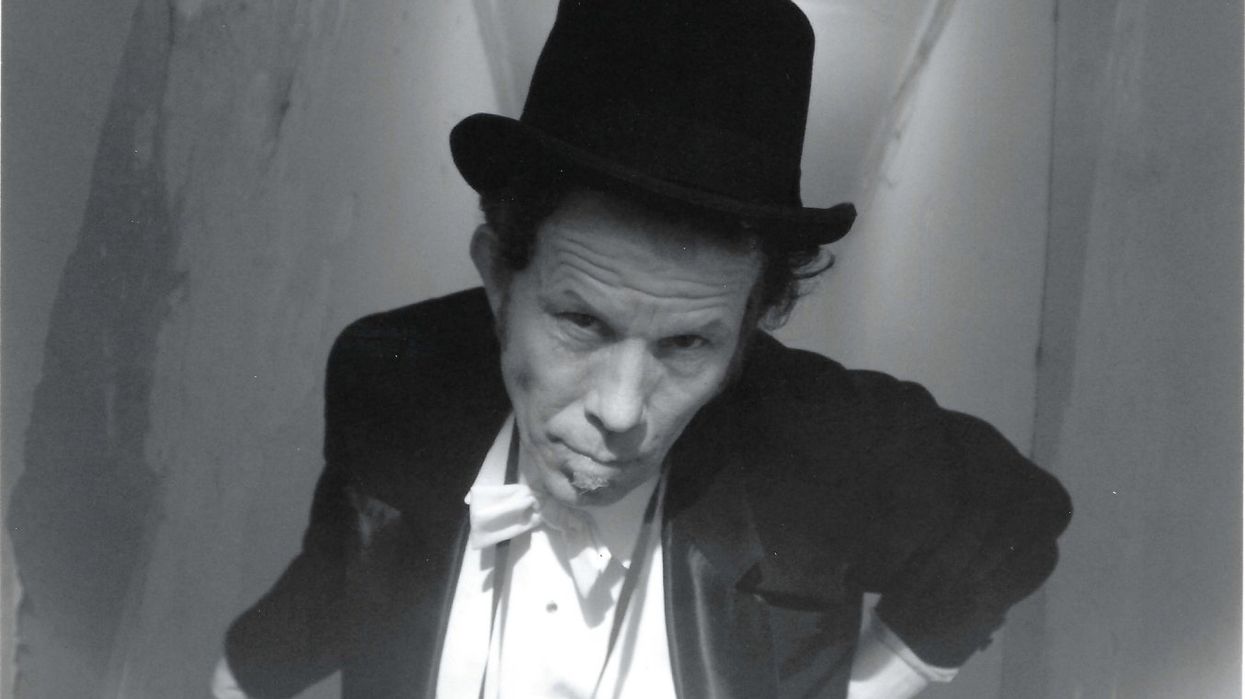

My favorite example, and also my favorite living songwriter, is Tom Waits. Whether you hear Tom crooning in his early post-Tin Pan Alley phase on a song like 1973’s “Ol’ 55” or whooping and cawing through 1987’s “Temptation,” accompanied by Marc Ribot’s gnawing guitar solo, or raving through 2011’s “Bad As Me,” recorded well after his conversion to avant troubadour … it all sounds like Tom Waits. And not just in the vocals and arrangements—although those are unmistakable. There is a rock-bottom sentimentality to much of his writing, which is consistently literate and poetic, and he has a way of drawing on roots-music sources in unlikely, sometimes outright weird contexts. He’s also a capable actor, but anyone who has seen Tom onstage, even before his first major theatrical role, in 1986’s Down by Law, knows that. I understand that everybody isn’t as fond of Tom’s work as I am, but that doesn’t matter. What does is that he is always recognizably himself—that he has a unique artistic character.

“What matters is knowing your own creative truth and embracing it.”

So, the point is, how do we follow in the footsteps of all the above to discover who we are artistically and bring that to play in our own work, in a way that conveys our distinctive creative character to anyone who hears our music? And once we do that, how do we keep growing while staying true to ourselves? There’s no pat answer, so it’s not as easy as soldering or even learning to blaze on scales for Instagram. And developing a unique artistic character is not important to everyone. There’s a lot to be said for just playing guitar and performing covers and having a whale of a time. But for those of us making original albums, trying to establish a sound or style that is authentically our own, trying to expand the envelope of genre, or do whatever the heck it is that lets us be us … well, it’s a lifelong DIY project.

The tools can’t be ordered online. They’re imagination, inspiration, honest evaluation, and the proverbial 10,000 hours. Along the way, decisions need to be made—about the playing approach and gear you might need to create a sound of your own, about really workshopping your songwriting and composing to get to a place where you hear that what you’re creating is authentically yours and not a diluted version of one of your heroes, about deciding exactly what you want your music to do. (A good way to arrive at the latter is working out an elevator pitch that explains your music to a stranger in as few words as possible. Decoding it for them also decodes it for you.)

It doesn’t matter how others judge your work. What matters is knowing your own creative truth and embracing it. Besides, it’s not always, or even often, easy to get others to embrace your vision, but that doesn't matter, as long as it’s your vision—and you know it, deep in your heart and brain.

Sure, gear is great and important, and I could talk about it all day. (Just ask my wife, Laurie, who has done her best to stay awake during many of my obsessive conversations with gearhead friends.) And learning how to mod it or make it so it best serves you is important. But if you have a creative vision, what’s most important is pursuing that vision, nurturing it, and truly owning it—until you and that vision are wholly the same thing.