Most artists pan for gold when they record, but only a few consistently find it. Lucinda Williams has been a remarkably successful prospector since she made her landmark 1998 album, Car Wheels on a Gravel Road. The daughter of poet Miller Williams had displayed her own gift for telling sharp-eyed stories since releasing her second album and first collection of all-original songs, 1980’s Happy Woman Blues, but with Car Wheels, she arrived at the crossroads of country, blues, rock, and folk that she’d been driving toward—in Cadillac style.

Since then, Williams has polished her articulate gemstones of song even more, cutting six albums through 2014 that cracked the Top 30 and established her as the queen of the song-driven, roots-based genre dubbed Americana. She’s also perfected a rhythm guitar style that’s ideal for the tension and release at the core of her powerful, buttermilk vocal performances. Syllables melt in her mouth, thanks in part to her Louisiana drawl, but they can also sting like the notes of a Stratocaster or a trumpet. And her guitar, which she beats like a thief, propels and lays back with similar flexibility and force. It’s not always metronomic, but exactly where it needs to be.

“Over the years, I’ve mastered something with my right hand, just from playing so long,” Williams explains. “When I first started making records, my guitar wasn’t seen as the launching pad for my songs. In the studio, they’d just play around me. But now, it’s where everything comes from. Sometimes I put the guitar down when we’re recording a song at the point where it feels like the band is getting the right vibe, so I can concentrate on my singing, but without my guitar playing leading the way in, it just wouldn’t be right.”

Now Williams has taken a new turn with The Ghosts of Highway 20. It is a cosmic folk-rock masterpiece, with a sound built on the guitars of Williams and accomplices Bill Frisell and Greg Leisz—MVPs of the jazz and singer/songwriter realms, respectively. The two-disc set is a fusion of visionary artistry. Leisz is a subtle craftsman who has spent his life accumulating the skill to build perfect frameworks for songs. Frisell has mastered sound, tone, and phrasing in a way that can transform a songwriter’s labors into something almost incorporeal. And Williams’ voice and lyrics conjure places, people, attitudes, and events that straddle the past and present in a way similar to the authors Gabriel Garcia Márquez and Barry Hannah.

Maybe the term to describe The Ghosts of Highway 20 is magical surrealism. The album brushstrokes its way through 14 songs that illustrate death, struggle, heartache, abandonment, and the people and places bound by them, here and in the spirit world. But it’s too beautiful and mesmeric to be depressing. Thanks to the warmth of Williams’ voice and the burnished intelligence of Frisell’s and Leisz’s guitars—which create a transcendent refuge for these lost souls and places—the light of joy glints everywhere.

“I think it reflects a vision that’s not negative, but older and wiser … mature,” says Williams.

In addition to her own ghostly evocations of the past, like the title number, and “Dust” and “Bitter Memory,” which weave the loss of Williams’ and her producer/manager/husband Tom Overby’s parents with the faded beauty and ugliness of the South into their emotional fabric, Williams recorded songs by two other distinguished writers: Bruce Springsteen’s blue collar requiem “Factory” and Woody Guthrie’s previously uncut “House of Earth.” And the album’s capper is the majestic, near-14-minute “Faith and Grace.” The number, featuring only Frisell on guitar, is an exploratory gambol based on a spiritual by blues legend Fred McDowell that Williams compares to John Coltrane’s rapturous “A Love Supreme.”

“Bill is really why the album sounds like this,” Williams explains. The majority of the tracks were cut at the same time as those for her previous release, 2014’s more conventional—if it’s fair to label the work of a songwriter/performer as superior as Williams that way—Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone. “It became obvious all the songs that Bill played on fit together beautifully,” she continues, speaking by phone from her home in Los Angeles. “We knew we had something special and organic. That’s how it is working with a genius.”

Did you have this album’s sound planned when recording began?

Everything is approached in a fairly organic fashion. It’s just bringing the right musicians together. Bill Frisell, right off the bat, is going to lend that kind of atmospheric thing. It’s just the way he plays. And having Bill and Greg Leisz together … we don’t think about it. Everybody just plays. And then we listen to what we have.

Since this album and your previous release were mostly recorded at the same time, what determined the songs that went on each?

Everybody asks, “What’s the theme of the album?” And they mean the themes of the songs, like they’re all part of the same story. And I guess sometimes that can happen, but we don’t sit down and say, “Well, this song is about Louisiana and this one is about Highway 20, so they go together.” It doesn’t work like that. It’s what fits sonically. And it’s just a happy coincidence this time that the themes of the songs also work well together.

So you didn’t write them as a suite?

No. I had some of them already. Some I wrote later and added on, like “Ghosts of Highway 20,” “If There’s a Heaven,” and “If My Love Could Kill.” And one is among the oldest songs I’ve ever written, that Tom discovered on an old cassette tape: “I Know All About It.” It used to be called “Jazz Side of Life,” but we changed the title. I probably wrote that in 1980 and put it on the shelf. I’ve saved all these acoustic cassette tapes in a big trunk, and Tom was going through archiving them and ran across this song. I thought I’d outgrown it, but he said, “No it’s great.” So I brought it up to my standard now as a writer and then we cut it, and it was just amazing. Sometimes there are happy surprises like that.

The line-up that recorded the improvised tune “Faith and Grace” includes (at center, beginning third from left) Bill Frisell, Carlton Davis, Lucinda Williams, and Ras Michael. Photo by Peggy French

Why the Springsteen and Guthrie songs?

The Woody Guthrie has an interesting story. We were playing a festival in Germany, and Nora Guthrie, who is Woody’s daughter, and her husband came to the festival and we ended up hitting it off and hanging out afterwards, drinking and talking about socialist politics. She’s an old leftie. Some time later she sent me the lyrics to that song and said, “These are really kind of out there for Woody, but of all the people I thought might be able to tackle this, it would be you if you want to put these lyrics to music.”

What I learned was, this was written when Woody was traveling west and ended up in Arizona. For the first time, he saw adobe structures and he was really impressed. And he called them “houses of earth.” Tom thinks that’s metaphorical—the house of earth is the woman. But I’m not sure. It’s pretty racy for that day and time. For example, one of the lines is, “I can teach you things that you could show your wife.” It’s an empathetic look at a prostitute. I first performed it at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C., and somebody with me said, “I’m pretty sure this is the first time anybody’s performed a song about a prostitute at the Kennedy Center.”

Tom is a huge Bruce Springsteen fan. “Factory,” he turned me on to. He grew up in a factory town, in Austin, Minnesota. His dad worked at the Hormel meat packing plant for 30-plus years, so that song really resonates with him, and me, too. We worked it up for playing the Fillmore in San Francisco one night, during the Occupy Wall Street movement, so we dedicated it to the movement, since it’s a song about working people. Tom’s dad passed away a few months before mine did, year before last. So it’s a combination thing—kind of a tribute to his dad. That line, “Men walk through these gates with death in their eyes.” Tom says, “I’ve seen those men walk through those gates. I could have been one of those guys.”

What do Bill and Greg bring to the game individually?

Greg and I go way back to the ’80s, when I first got to L.A. He’s such a great multi-instrumentalist, with pedal steel, lap steel, and guitar. At the end of each night, when the session ended, it would be Greg, Tom, and me listening to what we had. And Greg has great suggestions. One night I said, “Tom, we need to make Greg co-producer, because that’s what he’s doing.” It helped to have him and David Bianco, the engineer, contributing. We ended up making a great team.

The way I like to work is very democratic. When we do a track, we have three or four live takes and we all listen at once. It has to do with the bass and drums, and getting the vibe locked in there. If we’re lucky we get the one with the bass and drums vibe locked down and the best vocal, because somebody can always go back in and redo some guitar.

With Bill, nobody ever said a thing to him. He’d just play. I’d show the songs to the guys, we’d go over a song until we had the arrangement, and then, it’s “Let’s go!”

Not everybody gets to hear him do this, but Bill can play any style—even a Jimi Hendrix vibe. He doesn’t always get a chance to do that. He does his floaty, ambient thing, but he can also just tear it up.

Bill Frisell and Lucinda Williams take a break in the lounge at Dave’s Room in North Hollywood, California, during the sessions for The Ghosts of Highway 20. Photo by Peggy French

What was it like to record “Faith and Grace,” which was clearly improvised?

That was the high point. Here’s how that started. There’s a DJ in L.A., his name is Native Wayne [Jobson], and he’s been telling Tom, “You need to get Lucinda down to Jamaica to record with the great musicians there.” At one point when we were in the studio, we ran into Wayne and he said, “I’ve got these guys in from Jamaica. Let me bring them down to the studio.” So they came in and set up.

Ras Michael, who plays hand drums, is the head of the Rastafarian church in L.A. He’s the real thing. He had on all these colors and medallions and a long beard and dreads, and he just kind of sits there and smiles. Talk about a vibe. And the drummer, Carlton Davis, played with Peter Tosh and was in the room when Peter Tosh was shot and killed. He was shot, too. That guy never missed a beat. I could see him playing through the vocal booth, and it was perfect.

But I was just terrified. I said, “What are we gonna do? We’re not doing a reggae song.” We settled on “Faith and Grace,” which I learned from an old “Mississippi” Fred McDowell recording he did with his wife and some gospel singers. I got the lyrics from the album and adapted them, and took some of the Jesus stuff out so it could be non-denominational. I started singing the song, to show it to everyone, and after a couple go-rounds they all fell in and we kept going. It was an experience. Not like jamming. It was a mantra. I’m just going off and improvising, and the voice you hear in the background going “ah-hoo” is Ras Michael. Every so often he would just wail. Nobody told anybody what to do. Bill is the only guitar player on the track. The entire version is about 18 minutes long, and when we were done, I went, “Oh my god! It reminds me of John Coltrane’s ‘A Love Supreme’ or something.” We edited it down a little for the album, but the only reason it’s two CDs is that song is so long.

Lucinda Williams’ Gear

Guitars

1954 Fender Esquire

• Mid-’70s Fender Deluxe Thinline Telecaster

• Gretsch Penguin

• Gibson J-45

• Martin D-28

• Baby Taylor

• Bedell parlor guitar

Amps

• Victoria 1x12 combo

Strings and Picks

• D’Addario EJ17 Phosphor Bronze (.013–.056)

• D’Addario EXL115W (.011–.049)

• Dunlop Medium Shell Plastic Thumbpicks

• Dunlop Nickel Silver Fingerpicks (.020)

What guitar do you prefer writing on?

I keep an old Martin D-28 … not a really valuable one, a ’72. That’s the one I usually write on and keep at home. I took the pickup out a long time ago. I started using Gibson J-45s on stage. They seem to be a little meatier. But this Martin has got that vibe. It’s kind of my magic guitar.

I’ve really been enjoying smaller guitars. I got a Baby Taylor to take on the road. That’s a sweet little thing to take around instead of trying to fit a regular-size guitar on the bus.

A few years ago a guy came out to the house and dropped two Bedell guitars off. One was regular sized and one was smaller. They sat in a closet, but they look really nice. After the last tour my Gibsons all ended up at Third Encore, where we store our stuff. So I picked up the little Bedell and used it a few times to work on songs. I never change the strings on my Martin, and it clearly needs to be taken in. So I used this bright shiny little guitar.

Do you still play your ’54 Esquire?

Tom won’t let me take it on the road anymore. It’s worth about 35 grand. I just play it in the studio now. Onstage I either play a J-45 or a Deluxe Thinline Tele. It’s an older one. I was playing a Trussart. They’re beautiful, but they’re just so heavy. And I recently picked up a Gretsch Penguin in Nashville. I don’t like to have too many guitars onstage. I get overwhelmed by choices. Stuart Mathis, who plays guitar with me, has six or eight onstage. I don’t need to have more than three. I don’t need too many knobs. And I don’t need a whammy bar.

How did you first fall for the guitar?

I started playing in 1965 when I was 12, at the height of the folk music thing. The guy who taught me had a rock band and he would come over once a week. Rather than bog me down with theory, I would pick a song for that week’s lesson and he would show me the chords and fingerpicking for that song. So I learned about guitar by learning about songs. “Puff the Magic Dragon” was one. You have to remember, I was 12. One of the first songs I learned was “Freight Train” by Elizabeth Cotten, ’cause you could pick the melody out.

I played the 12-string for a while. I was playing out a lot by myself and figured it would have more sound. I had a Martin 12-string. I feel very blessed and thankful, now, that I learned that fingerpicking style.

YouTube It

Although Bill Frisell is absent, two other prominent guitarists in Lucinda Williams’ history, Greg Leisz and Buddy Miller, accompany her for this performance of “Blessed,” the title cut from her 2011 album, during that year’s Americana Music Association’s annual awards show at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, where she was presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award in the Songwriter category. Williams’ open-handed strumming on a Gibson J-45 drives the tune. Leisz takes one of his patented tasteful, melodic solos at the 1:50 mark, and comes back for a more exuberant cleanup round at 3:35.

And what was your first guitar?

A Sears Silvertone my dad bought for me. I was always interested in music, but I wanted to learn quickly and didn’t have the patience for piano. My mother was a piano player, so there was always a piano in the house and sheet music, but I couldn’t read the sheet music and I wanted to play something so badly … I was really frustrated. I wanted to play and sing.

A friend of my dad’s, another poet, had left his guitar over at the house. It was broken and beat up. I remember picking it up and messing with it a little bit, so it was obvious I wanted to play, so my dad went and got me a Silvertone. And then I moved to listening to bands like the Lovin’ Spoonful, the Byrds, and Bob Dylan.

Besides Bill, Greg, and Stuart, you’ve had a long line of distinguished guitar players in your band—Gurf Morlix, Doug Pettibone, Duane Jarvis, Kenny Vaughan, Buddy Miller, and Bo Ramsey among them. What do you look for in a lead player?

It’s hard to find a good folk, rock, country, and blues player who is also a lead player. That’s what I need. More and more I put down the guitar so I can concentrate on singing. And the rhythm playing is as important as good lead lines. But at the same time, my playing and my voice are welded together for a lot of my songs. Somehow all of those parts need to fit together naturally.

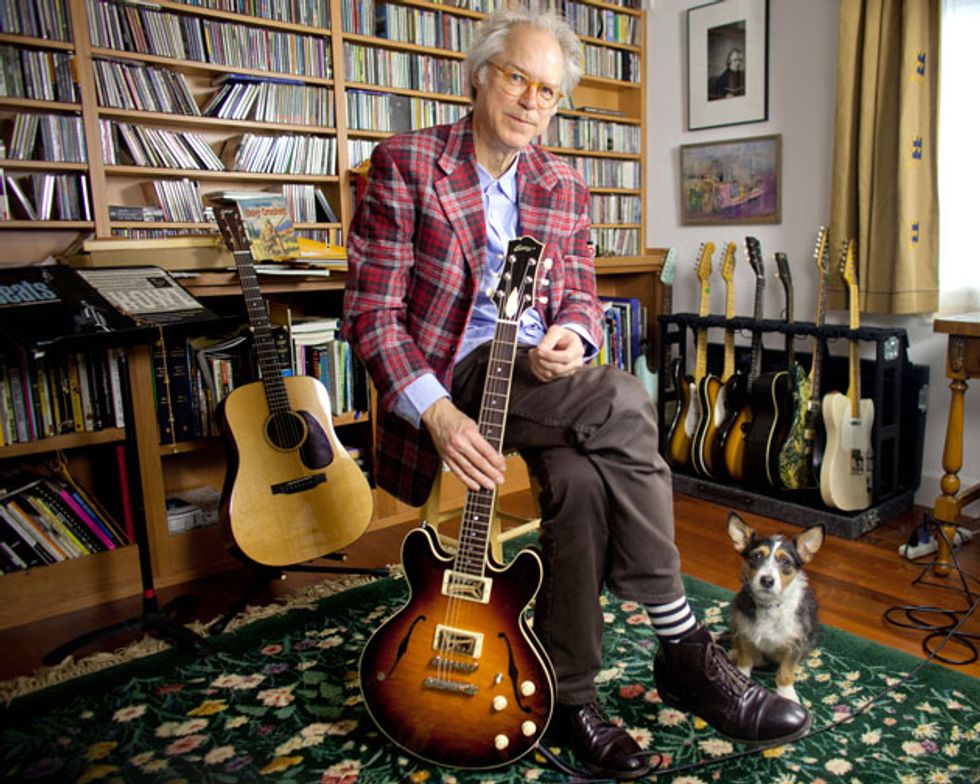

Whether he’s flying to a session or tour dates, Bill Frisell travels light—with one Telecaster and a modest pedalboard. But he confesses to having a roomful of gear at home.

Bill Frisell: Sounds of Innocence and of Experience

Fans of nuanced guitar playing with a dollop of the outré know Bill Frisell’s name. Somehow—even after roughly a half-century playing 6-string and a 2005 Grammy win for his 22nd album, Unspeakable, followed this year by his fourth Grammy nomination for his 2014 album Guitar in the Space Age!—he seems to find that surprising.

“I can’t believe it,” he says about his latest Grammy nod, for an album that puts his inventive spin on selections from the great American and British Invasion rock songbook: “Pipeline,” “Rebel Rouser,” “Telstar,” “Tired of Waiting.” “I still don’t even really understand what that means, but it’s nice,” he adds, quietly.

Like his brand-new 2016 album, When You Wish Upon a Star, which revisits classic TV and film themes from David Rose’s Bonanza melody to Bernard Herrmann’s music from Psycho, the material for Guitar in the Space Age! is plucked from the soundtrack to his childhood. For Frisell, it comes from a time when guitar playing was new and mysterious, at least to him, and he strives to explore it with a mix of his accumulated knowledge and the same naiveté with which he originally encountered the tunes of the Ventures and Duane Eddy.

His blend of innocence and experience resonates throughout Lucinda Williams’ The Ghosts of Highway 20, and allows him to take the music to places most guitarists supporting a singer would not. Although Frisell has played on three of her albums, this is the only one that features him on every track, to the extent that he is its sonic North Star.

“Her recording process is incredibly courageous,” Frisell says. “She would show us the songs and then, without anybody getting any instructions, really, we’d all begin playing. And I felt like whatever we played had an impact on what she was singing, and what she was singing had an impact on what we were playing. I’ve been a fan since Car Wheels on a Gravel Road, and I love her writing and singing and guitar playing, but this felt so truly in the moment and mysterious, and we heard that in the playbacks while we were recording. You could really feel each song come to life, and that just reaffirmed my feelings about what a real person she is.”

Frisell first performed with Williams at a Seattle concert, when his former student, Kenny Vaughan, who now plays with Marty Stuart’s Fabulous Superlatives, was in her band. “They invited me down to play, and I figured I’d sit in for a song or two and that would be nice. But just before we went on, Lucinda arrived and introduced herself, grabbed my arm and said, ‘I’m so glad you’re here—let’s go.’ And walked me right onto the stage with her to play the whole concert. I was kind of nervous, but I was also such a big fan that after a few songs everything seemed really natural.”

Playing with Leisz during the Ghosts sessions was equally natural. They’re longtime friends and collaborators, and Leisz has played on several of Frisell’s albums. “Greg and I know exactly how to fall in place with each other, and we’re really comfortable playing together,” says Frisell, “but even at that, there was an element of danger during the sessions. It’s so spontaneous that you always feel like the songs are either going to come together perfectly or entirely fall apart. But Lucinda is such a good guide.”

Frisell says his playing on the track “Faith and Grace,” the set’s concluding transcendentalist opus—with Williams’ chanting, the wails of Ras Michael, and a weave of instruments that shimmies like a rainbow-colored sheet in the breeze—“is the best playing I’ve ever done. It was just amazing, and we did it all in two live takes.” His backwards melodies, sonar blips, chiming chords, horn-like statements, and gutbucket rock licks are, indeed, entrancing. But that can be said about the way he wields his Telecasters on almost any track. On “I Know All About It” he creates the aural equivalent of a rippling seascape, playing what sounds like a guitar trying to morph into a Hammond B-3 organ.

Bill Frisell’s Gear

Guitars

• J.W. Black T-style with Mastery Bridge and Callahan pickups

• J.W. Black T-style with Bigsby, Mastery Bridge, and Callahan pickups

• Nash T-style with TV Jones Filter’Tron neck pickup and Lollar Tele bridge pickup

Amps

• 1958 Fender tweed Deluxe

• Fender blackface Princeton Reverb

• Princeton Reverb modded by Howard Dumble

Effects

• Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer

• Electro-Harmonix Nano Pocket Metal Muff

• Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler

• Electro-Harmonix Freeze Sound Retainer

• TC Electronic Hall of Fame Reverb

• Strymon Flint Tremolo & Reverb

• Catalinbread Katzenkönig overdrive/distortion

• Voodoo Lab Pedal Power

• TC Electronic PolyTune

Strings and Picks

• D’Addario XL115s (.011–.049)

• Dunlop Tortex Jazz mediums

“I discovered this weird thing about playing with two amps,” he explains. “If I set the tremolo on one and not the other, and play in stereo, it kind of makes the sound go in and out of phase.” The quivering effect is also helped by his wiz status with a Bigsby, which he has on his Tele-inspired J.W. Black guitar.

Speaking to Frisell, his humility comes through as crisply as the notes of his guitar. Perhaps that’s a leftover from surviving the ’70s, when he was living in Denver, Colorado, trying to get his balance. “It was a really dark time,” he recalls. “I had been on the East Coast studying with Jim Hall, and then I moved back to where I grew up and was giving guitar lessons to high school kids who didn’t care at all about Charlie Parker and never practiced their lessons. I would walk around by myself, depressed. I didn’t have a girlfriend and I was living in a total fleabag transient one-room apartment.”

But in the ’80s, Frisell became the house guitarist for ECM Records after Pat Metheny, unable to make a session, recommend him for a recording with drummer/composer Paul Motian. He quickly became a staple of jazz’s cutting edge, and an innovator for his use of effects in the genre.

“Oh, I don’t know if I’m an innovator,” Frisell verbally shrugs. “I just like to mess around with sounds. I got my first fuzztone because of the trumpeter Freddie Hubbard. He got this sustained, buzzing solid sound from the trumpet, and I wanted to be able to do that on the guitar.

“I’ve been playing for more than 50 years, and with my technique and my sound it’s like, you can’t quite get there,” he explains. “ My tone … I feel like I’m always struggling with it somehow. But when you spend your whole life struggling, it feels like you get a little closer every day. Hopefully at some point you’ve accumulated something, but it’s hard for me to say what it is.”

Another recent project that displays Frisell’s perspective on roots music as an elastic form is his 2012 soundtrack for documentary filmmaker Bill Morrison’s The Great Flood. The movie uses historic footage and still photos to tell the story of the Mississippi River’s 1927 overflow, which influenced the course of 20th century American history. Frisell and his band traveled with Morrison through the region affected by the disaster—which inspired Delta bluesman Charley Patton’s “High Water Everywhere” and a host of other songs—looking for traces and the aforementioned visual treasures for inspiration.

“Initially, I thought we might do something based on classic blues and jazz, since we found material in St. Louis, Chicago, Memphis, Helena, Arkansas, Vicksburg, Mississippi … but in the end I decided to build something from the ground up,” Frisell says. His guitar and Ron Miles’ trumpet became the film’s narrative voices, echoing the majesty, loss, and rebirth caused by the flood in gracefully evolving movements.

“I’ve been so lucky its kind of crazy,” says Frisell. “I don’t feel like I have a real plan. I don’t set goals for myself. I just go along and opportunities keep presenting themselves. Something will be suggested or an opening will arise—and then I get to do it.”

Greg Leisz, here onstage at Red Rocks, brought a ’54 Fender Jazzmaster and “as many guitars as I could fit in my car” to the sessions for Lucinda Williams’ new album, which he also co-produced. Photo by Anjali Ramnandanlall.

Greg Leisz: Symbiotic Guitar and the Art of Supporting Songwriters

“This album is very special and unique,” says Greg Leisz, whose playing has become legendary for his ability to support singer-songwriters from k.d. lang to Dave Alvin to Jackson Browne, Tracy Chapman, John Fogerty, and Eric Clapton. “When I listen to it, it’s hard to really understand how it happened. There was no thought to how it was going to sound. We didn’t have a plan. It was just those people playing on those songs.”

Those people—the cast of Lucinda Williams’ The Ghosts of Highway 20—are primarily guitarists Bill Frisell and Leisz (Leisz also co-produced), Williams on acoustic and electric guitars, and her band’s rhythm section, bassist David Sutton and drummer Butch Norton. Val McCallum also played some guitar, when Frisell wasn’t available for the album’s final sessions.

Leisz and Frisell have played together on Williams’ albums before, including 2014’s Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone, as well as on Frisell’s own recordings. But this, explains Leisz, was different. “On other recordings with Bill, I’d been playing a lot of other instruments—pedal and lap steel—but this is really a two-guitar record. I have a relationship with him that goes back 20 years, but this is different because it’s all based around Lucinda’s songs. We’re really playing in the moment with her and, unlike the last album, she played her guitar throughout most of the recordings. When she keeps her guitar in her hands, it’s easier to keep the original feel of how she wrote the songs.”

Leisz says Sutton and Norton were also an important element of The Ghosts of Highway 20’s rooted yet open and ethereal sound, and the emotional richness of its songs. “The rhythm section on the last album played okay, but David and Butch play her songs differently and follow her lead,” he observes. “And that made a difference.

“As far as Bill and I, we just have to come up with parts that work with her and each other,” Leisz continues. “We’re just playing the songs together at the same time in the intuitive way we’ve developed. Bill has an approach that has been derived, in large part, by playing in instrumental settings where he is the ‘singer,’ so he’s not accompanying the songs by playing around the singer—which is what I’ve done for many years. When he plays with a singer, he’s almost harmonizing the vocal line. It takes up a lot of space, but it also creates space. That allows me to react to him and the singer at the same time. With Lucinda, these songs have a lot of raw emotional content, and in the studio we could feel it coming out of her and pouring through all of us.

Greg Leisz’s Gear

Guitars

• ’55 Fender Telecaster

• ’64 Fender Jazzmaster

• ’61 Gibson Les Paul Junior (pre-SG designation)

• Guild Starfire V

• ’56 Gretsch Firejet with DeArmond pickups

• 1941 Martin 0-18

Amps

• 1958 Fender tweed Deluxe

• Fender blackface Princeton Reverb

• Princeton Reverb modded by Howard Dumble

Effects

• Strymon El Capistan dTape Echo

• Strymon Flint Tremolo & Reverb

• Strymon Lex Rotary

• Arion Stereo Chorus

Strings and Picks

• D’Addario EXL140 (.010–.052) Tele

• D’Addario EXL116 (.011–.052)

• D’Addario NB1253 (.012–.053) acoustic

• Dunlop Zookies thumbpicks

• ProPik Finger-Tone fingerpicks

• Coricidin bottle-style slides

“With Bill and I, it’s really unique compared to putting almost any other two guitar players a the room. They’d tend to play similar parts, like chords, together, while Bill and I are crossing each other all the time. When I listen back to the album, I really can’t tell who’s playing what. That’s why we split ourselves in the mix. I’m on the left side and Bill is on the right.”

Leisz dives deeper into his modus operandi: “Since I first started playing, when I was 13 or 14, I was drawn into the melodic content of songs and have been interested in reacting to and playing with singers. I like to think I’m contributing to the melodic content while reacting to the emotional content. You have to know when what you’re playing might get in the way of the songs, and when I get to a place where I know I’m helping deliver a great song, I really dig it.

“I started out working with world-class songwriters, so I’ve had a lot of experience,” he continues, “but I don’t really know how I got to that place. By the time I was aware of what I was doing, I was already doing it. It wasn’t a conscious pursuit, but it was exactly what I wanted to do.”

Leisz first worked with Williams in the mid ’90s, although those sessions were ultimately scrapped in favor of pursuing what became Car Wheels on a Gravel Road, where he played 12-string guitar and mandolin. The Ghosts of Highway 20 is his fourth album with Williams, who he first encountered as a blossoming singer-songwriter in L.A.’s ’80s post-punk roots scene. “I think she was working in a record store,” he says.

“Today, Lucinda has a real strong sense of who she is,” Leisz offers. “As a writer, that’s always been true, but now more so than ever as both a writer and performer. She’s had quite an illustrious group of guitar players come through her band, and when you work with a lot of people you develop more confidence than you do working with the same group of people all the time. So she also became a great bandleader.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)