Nothing beats meeting your heroes—especially when they’re happy to share their secrets. In the late 1960s, then-teenaged Richard Lloyd, the Television co-guitarist and new wave pioneer, managed to get backstage and into the dressing rooms and inner circles of people like Jimi Hendrix and John Lee Hooker. He asked questions, took mental notes, and absorbed lifelong lessons about the guitar. He put those lessons to good use, too, and developed an alternative, holistic approach to the instrument. That approach was enhanced by his left-brain orientation, plus his never-ending spiritual quest.

Lloyd also studied the teachings of mid-20th-century mystical teacher George Gurdjieff, and those studies—in addition to the impact they’ve had on his spiritual life—transformed his understanding of music. The result, which you can check out in a series of instructional videos and columns that appeared in Guitar World about a decade ago (now on DVD as The Alchemical Guitarist), is a complex, pattern-focused, vertical approach to the instrument based on an idiosyncratic understanding of the major scale.

Not surprising, his career has taken a similar, alternative trajectory.

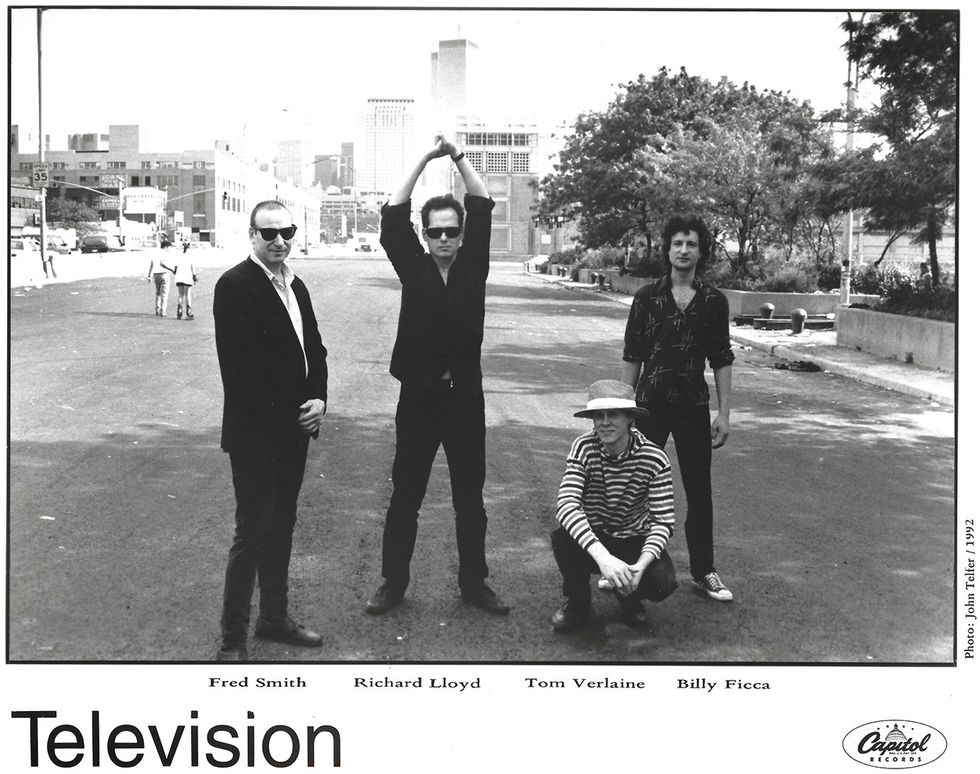

Lloyd came to prominence in the mid 1970s with Television, a group he founded with Tom Verlaine, Billy Ficca, and Richard Hell in 1973. (Fred Smith replaced Hell on bass in 1975.) Television, along with the Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads, and others, were integral to New York City’s burgeoning punk scene. That scene—which, except for a few bands like the Ramones, wasn’t really punk—was based out of CBGB, a club on the Bowery. The black-walled rectangular-box-shaped venue supported a smorgasbord of styles, like new wave, post punk, and art rock, that dominated the Top 40 in the ’80s, albeit in a more plastic, synth-drenched incarnation.

But those sounds in their pure, distilled form were Television’s home. Television was a guitar band—no wailing synths or bad hair for them—and their debut, 1977’s Marquee Moon, is an iconic testament to the early, pre-sellout days of new wave. Lloyd and Verlaine shared guitar duties and crafted tight, interwoven parts, and the band was a huge influence on later acts like the Pixies, Sonic Youth, R.E.M, and many others. Lloyd’s tone with Television, while often overdriven and warm, sounds sharp and somewhat stark when appreciated in context—and given his roots and early association with Hendrix, it was a clean break with the past.

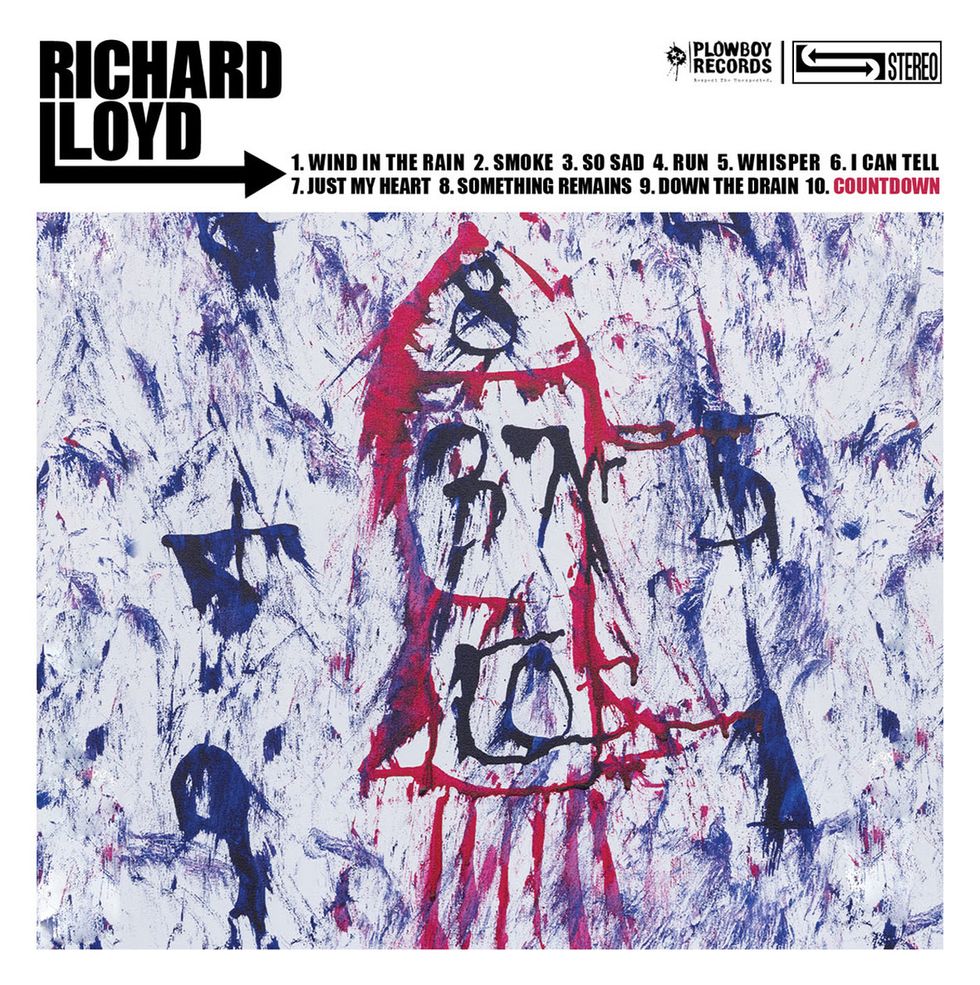

Lloyd left Television for the first time in 1978, after the band released its second album, Adventure. They reunited in 1992, and Lloyd stayed in Television until 2007. Along the way, he’s worked with other artists, including Matthew Sweet and X’s John Doe, released solo albums, and established himself as a sought-after teacher and alternative-rock elder statesman. His new solo album, The Countdown, is a collection of fuzzy, mid-tempo rockers that, along with the paperback edition of his 2017 memoir, Everything Is Combustible, was released in November.

Lloyd took some time to speak with us from his home in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where he recently relocated from Greenwich Village, about the things he learned from Hendrix and Hooker, his experiences with spirituality and Gurdjieff’s teachings, his unique approach to guitar, and some of the collectable gear he’s amassed (and lost) over the years.

John Lee Hooker once gave you advice about guitar playing—specifically about learning how to play one string at a time. Was your meeting with him a one-off or did you have a relationship with him?

No, that was a one-off. I went to see him in Boston, at the Jazz Workshop on Boylston Street. Back then, I just walked into the dressing room and sat down. Eventually, he took notice of me and he said—he pointed his finger at me, and he said, “And you, young man, what do you do?” I said, “I play guitar.” He said, “Are you good?” I said, “I don’t know.” He said, “No, no, no. You’re great. I can tell. Come over here and I’ll tell you the secret of playing the electric guitar.”

Then he cupped his hands and he whispered in my ear, “Take off all the strings but one and learn the one string up and down and down and up and bend it and shake it until the women go ‘oooo.’ Then put two strings on and learn two strings up and down and down and up.” I went home, but I didn’t take the strings off. I couldn’t afford to take them off—I didn’t have a replacement set. But I did practice what I call vertical knowledge, which is up and down pitch on a single string, a great deal. Jimi Hendrix had also suggested that to us—that we learn the neck that way.

TIDBIT: Lloyd stood in the studio’s live room with his amp, creating slithering lines of feedback, for the title track of his new solo album, The Countdown.

As opposed to horizontal playing?

Exactly. As opposed to playing it from side to side or across the strings—to learn the single string. In fact, some of Jimi’s solos … like on “May This Be Love,” are all on the B string. The entire solo. There’s another one that’s all on the G string: “I Don’t Live Today.” Except for the last note, it’s all on the G string.

He did that for tonal reasons?

I don’t know why he did it, but he could move up and down the neck pretty effortlessly. He knew his intervals. For instance, that solo starts on the A and goes up to a fifth of the A, and then down to the fourth, and then up a major third, and then a minor third, and a minor third, and then a major third. He’s building the chords on a single string, arpeggio style. It’s a very cool way to play. My solo on “Elevation” [from Marquee Moon] does the same thing on the G string. It goes up in A minor from the second fret to the 17th fret.

I’m asking because in the instructional videos you did for Guitar World, you talk a lot about Pythagoras, major-scale exercises, and using a single string. That comes from your conversations with John Lee Hooker and Hendrix?

It comes partially from them, but also from my study of music theory, which is based on ratio and vibrations—a man name George Gurdjieff, he was a spiritual teacher, and I am involved with his teaching.

He incorporates music into his spiritual philosophy?

Yes, he does. He takes the major scale as a way to look at reality. It is very interesting. It takes a lot of study to understand. That informed a great deal of my own musical theory and knowledge.

How so?

To concentrate on a major scale and all its modes and permutations. A single scale accounts for 84 scales. If you buy a scale book, you’ve got 84 pages of major scales, but it is really one scale that starts in different places on different pitches. You’ve got 12 pitches, and you’ve got seven modes—that’s 84—and you really only have to learn one pattern. The same with the pentatonic. There’s five modes, but only two of them are really used—the major and the minor modes of the pentatonic scale—but you really only have to learn one scale and then you just start it from a different place within the scale.

A Supro Black Holiday is Lloyd’s current favorite stage guitar. Inspired by the Res-O-Glas Supro guitars of the ’60s, the model has two single-coil pickups and a chambered mahogany back. Here, he’s at Nashville’s 3rd & Lindsley for The Countdown album-release concert that followed a book signing. Photo by Stacie Huckaba

And you take that around the circle of fifths and find it throughout the instrument?

Absolutely. And one of the reasons I love the guitar is that you’re in contact with a vibrating string. Unlike a piano, where you’re hitting a key, which then operates a hammer, which hits the string. It’s very polite in a certain sense, but the guitar, in a way, is rude and lewd. That’s why the troubadours in the 12th century caused such a ruckus, singing love songs and ballads on a guitar. It was beyond romantic. The ladies liked it and the guys didn’t.

Because you have physical contact with the sound-making device?

Absolutely. You’re not using a bow. You can use your fingers or you can use a pick. I use a plectrum myself, almost all the time. Sometimes I claw back, it’s called, if I am doing things like sixths or even tenths: I play with my first finger and thumb with the pick and then I use my middle finger or ring finger to claw back a second string, to do intervals.

And do you work through the harmonics on each string as well?

Yes. You can find the major scale embedded in the first 16 harmonics, but the harmonics are useful after you know everything else. Sometimes I’ll go up and down the string checking out the harmonics. We used to tune with harmonics, because the fifth fret on one string equals the seventh fret on the next string going up in pitch. Like the A to the D. It works for all except for the G and B strings, because that’s a major third.

lead guitar playing.”

You’ve mentioned in interviews that music is your meditation and prayer. How is music a spiritual pursuit?

I think that in the ancient world there was no difference between religion and science or spirituality. Alchemy and chemistry were the same thing. Astronomy and astrology were the same thing. It’s only in the modern era that this got separated. People started to play secular music. Before, everything was sacred about music. Personally, I think it still is something sacred, because you’re dealing with vibrations, and the universe is made of vibrations.

And so the connection you have with people is more intuitive as well.

Sure. I used to play in fourths while I was practicing the guitar—I had an acoustic guitar and I would play fourths on a rooftop in Manhattan—and I swear that little spiritual creatures used to come around to listen. Playing in fourths is so compelling that it draws good spirits around you.

Specifically a fourth? Not a third or some other interval?

No, specifically fourths. A fourth is an upside down fifth. It’s either the cycle of fourths going up or the cycle of fifths descending, and they are the same thing. If you play along that line, it’s a very spiritual practice.

Fourths are more intuitive to the guitar, too.

The strings are tuned in fourths. The only one that’s missing a half-step is the B to the G, which is a major third. That is not a perfect interval, but it’s the most consonant of the non-perfect ratios.

Guitars

1961 Fender Stratocaster

Supro Black Holiday

Epiphone Casino

Eastwood Classic 6

Vintage-brand S-style V6MR

Amps

Supro Black Magick

1965 Supro Thunderbolt

Effects

Vertex T Drive

Dunlop Echoplex Preamp

Vintage Echoplex (studio only)

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky Classic Rock N Roll (.010–.046)

D’Andrea Snarling Dog Brain .88 mm

With all this knowledge, when you’re actually playing or writing songs, do you think about this stuff or do you turn it off and just play?

I basically go by instinct. I turn my brain off [laughs], although it won’t turn itself off and there is nothing I can do about that. But I don’t actively think, “Now I am moving to a fourth. Now I am moving to a sixth.” I just don’t think in those terms once the music starts.

Do you use dissonance, too?

Yeah, but not so much in my work. In practice I do. I love dissonance because it demands resolution. You can wait until it resolves and it splits the tension. It is pretty fantastic in lead guitar playing. The other thing the guitar is great for is half-steps. Microtonalities. In that sense it’s a lot like a sitar, because you can bend the strings.

Dissonance creates tension and you resolve it, or do you leave it unresolved?

The human brain wants it resolved, that’s for sure. If you leave it dissonant, the mind imagines the resolution. Or the mind goes into a state of distress [laughs]. The beginning of “Purple Haze” is tritones, which they used to call the devil’s interval. That’s the most dissonant you can get.

You met Hendrix through your friend, the guitarist Velvert Turner, who was also a friend of Hendrix?

That’s correct.

You mentioned the single string. What else did Hendrix show you?

Mostly he taught through his songs. In the early days, he taught us his first records—the first and second record.

On your tribute to Hendrix, The Jamie Neverts Story—Jamie Neverts was the code name you and Velvert had for Hendrix—you mostly cover songs from those two albums.

That’s right. I didn’t want to do guitar hero stuff, like “Voodoo Child (Slight Return).” I wanted to do those shorter songs, which were more like pop stuff. He didn’t have much time in the studio back then. They’d book two hours and you’d have to do, like, three songs in the two hours and then you’d come back and put leads and vocals on. I spent more time trying to get clearer images of his solos and stuff. I didn’t bend the songs too much out of their structure.

Hendrix’s sonic footprint was pretty high tech for the times—he used a lot of effects—but you didn’t take that from him for your own work.

No, I am not an effects guy. Occasionally, I’ll use an effect, but for the most part, it’s just been a guitar into an amp. You get the purest sound that way. With Television, those records are without any effects at all. The only effect was me doubling parts, which gives it a kind of chimey-ness. Not chorusing, but similar.

In this Capitol Records promotional photo from 1992, the members of Television are, from left to right, Fred Smith, Richard Lloyd, Tom Verlaine, and Billy Ficca. Photo by John Teller

Do you get your gain from letting the amp break up naturally?

Yeah. I mean, I am using some pedals live and I have been for a number of years. Lately, I’ve been using a Supro reissue. For a while I was using a Thunderbolt, and now I’m using a Black Magick. They break up pretty good, pretty early. You can pretty much get your tone out of the amp. I had about eight of them at one time. I sold a bunch off in the ’90s, but I kept my ’65 Thunderbolt. I’ve kept a number of others. They’re numbered; I don’t know the names of them. I am a big fan of Supro.

That’s what you’re using on those first two Television records?

On the third one [1992’s Television]. For instance, the solo on “Call Mr. Lee”—that’s through my Supro ’65 Thunderbolt, straight in, turned all the way up.

What were you using earlier?

We started with Fender Supers and then we switched. In the studio, I was using Danelectro/Sears/Silvertone amps. We had a number of amps. One song had an Ampeg Jet. It’s a small amp, but you don’t need a large amp to sound big in the studio.

For your clean tone, do you ride the volume knob on your guitar?

Absolutely. Yup.

In the studio, do you stand in the room with your amp when you’re playing?

Sometimes. Sometimes I am in the control room. It depends. On The Countdown, I was in the room with the players, the bass and drums, and on the song “Countdown,” the lead is all feedback, so I had to stand in proximity of the amp.

How has your approach to recording and tone evolved over the years?

I don’t know if it’s evolved so much as every time you have a different opportunity to try different things. I recently got an Epiphone Casino, which I love. I got it because John Lennon played it and you can get an incredible, great sound out of it. I also have a Supro, a new one, called the Black Holiday guitar, which is my go-to guitar now. And a Strat, and anything else that might pop up. I don’t tend to use Les Pauls. I tend to stay with single-coils, not humbuckers.

Do you still have that 1961 Strat with the great paint job—a pattern of sweeping lines on the body—that you played on Marquee Moon and Adventure?

I do. It’s in storage and it’s locked up and everything along with it, its appraisal and all of that. That’s a museum piece. I don’t play it out. The first tour that I didn’t take that on, all of our guitars got stolen in Brussels. I must have had some foresight or something. I lost a couple guitars but not that one, thank God.

Did you do the paint job yourself?

I didn’t. I got it that way and no one knows how it got painted that way. It must have been right away, shortly after the first purchase. I think it was originally a gold top.

come around to listen.”

Did you do any mods or is it stock?

The electronics are all stock. I changed the tuning pegs because it wouldn’t stay in tune, but that’s the only adjustment. I did change the frets. I still have the old ones, but I put on kind of jumbo, Les Paul frets on the Strat. I got the originals in a bag [laughs], along with a few other things from that guitar. The original tuning pegs.

On Marquee Moon and Adventure, you got to record with engineer Andy Johns, who was known for his work with the Stones, Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton, and so many others. Did he have any insights or tips that helped you with tone or miking guitars?

He pretty much left us to our own devices, but what a great recording engineer. Incredible use of microphones and very little outboard equipment, but some—mostly compressors and EQ. He was a fantastic recorder, that’s for sure.

What mics do you prefer?

Nowadays, I use ribbons and a great combination of the Royer 121 and something called a Turner. Turner was a company in the 1930s. First they made headstones, then they made PAs for funerals—and they also got into shortwave radio mics—but they had two or three that were high-end mics. But they’re not very high end. They’re not condensers; they’re dynamic mics, like a [Shure SM] 57, but a pretty flat sound. I love them.

Yours are vintage or copies?

That company went out of business thousands of years ago. I have Tuner mics that are older than Stonehenge.

What pedals do you bring on tour?

I had a Tube Screamer TS808 that I used for a long time. It and a couple of other pedals got lost by Air Canada, which really upset me. They only pay by the pound when they lose your luggage. They don’t pay the value, so I lost that. I wasn’t able to replicate it. The new ones, the reissues, even if they say they have the same chip in them, for some reason they just don’t sound the same comparatively. I had one from the first year that they came out. I also have a Boss overdrive, the yellow one, that Overdrive OD-1, which had the same chip as the Tube Screamer. That’s a pretty good overdrive pedal. Lately, I’m using a Vertex T Drive. I have an Echoplex preamp, which adds up to 8 dB to the signal and softens it a bit. And some kind of delay. On one tour I took an actual Echoplex around the world and, surprisingly, it kept up. They’re infamous for breaking and it didn’t break. I was lucky.

A lot of the guitarists in the New York City bands that you came up with were so different: Television, Talking Heads, Blondie, the Ramones. How was it a scene? It wasn’t a genre.

No, it certainly wasn’t. The scene was that everybody played original music and no covers. That was the basis of it, and there were an amazing number of bands who did not sound the same: the Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads, Television, Mink DeVille, the Shirts, the Dead Boys … there were tons and they all sounded different, which was fantastic. We weren’t in competition then so much as we were able to cross-pollinate our audiences.

And everyone got signed.

Pretty much everyone got signed, that’s right. It took three years for Television to get signed. A lot of the bands had been signed, but we kept turning record companies down. We didn’t want to have a producer come in and we didn’t want to have to make a record on a $2 budget. We waited and went with Elektra because they had Love, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and the Doors.

After Television reformed in 1992, they made their third album, simply called Television. The single was “Call Mr. Lee,” a sonic nod to ’50s and ’60s noir/spy movie soundtrack music. You can catch the interplay of Lloyd and Verlaine during the instrumental break, and eyeball Lloyd’s ’61 Strat, with its distinctive paint job. Oh yeah … and Lloyd rips it up from the 3:00 point on.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)