Left to right: High on Fire’s Matt Pike, Des Kensel, and Jeff Matz. Photo Credit: Travis Shinn

| Click here to watch our Rig Rundown with Matt Pike |

High on Fire guitarist Matt Pike’s previous band, the legendary underground rock act Sleep, helped reinvigorate this long-lost sound once championed by bands like Black Sabbath and Blue Cheer. Sleep and bands such as Kyuss (Josh Homme’s band before Queens of the Stone Age), Neurosis, and veteran rockers Saint Vitus, helped pioneer a revival of the early days of heavy rock by playing droning guitar riffs through simple rigs—often not much more than a loud, fuzzed-out amp. At the time, rock of this fashion wasn’t exactly in style. More sterilized forms of the genre were all the rage, because huge, epic jams that clocked in at 15 minutes weren’t conducive to radio play. A defining trait of these underground bands was that they lived for the thrill of the stage and didn’t need cheap gimmicks or cheesy distractions to take attention away from the music.

After Sleep’s demise, Pike formed High on Fire with drummer Des Kensel. The sound, while still retaining the Sabbath-esque doom elements of Sleep, was infused with the rawer elements of Motörhead. Pike’s voice and persona draw a lot of comparisons to Motörhead’s infamous frontman, Lemmy Kilmister. After laboring and touring for 12 years, HoF has garnered fans the world over and has become one of underground rock’s biggest success stories. Just recently, Metallica handpicked them to open for them on a two-week tour—a sign that years of hard work has paid off.

We recently caught up with Pike in Madison, Wisconsin, during the band’s tour for their fifth studio album, Snakes for the Divine (E1 Music), to talk about metal’s place in the music business, his nine-string First Act guitar and dual-amp rig, and what it takes to be a torchbearer in the latter-day metal underground.

How did you get into playing guitar?

Basically, I was a juvenile delinquent in Denver. One of those bad kids in high school. I did things like drop acid all of the time, hang around the smoking pit, chase girls, whatever. One of the things that I was always really capable of was playing guitar, and I had been playing since I was 8. I was pretty good at the time, but I didn’t think about it in a “I’m the best ever” sense. I just really liked to play and only cared about getting better and better at it. I’d eventually become the guy in school that taught other guys songs. Stuff like Mötley Crüe and Metallica. I eventually got caught up in stealing car stereos, then eventually the cars straight up. It was completely my own fault, and I paid for it by going to military school and juvenile hall. I ended up taking the rap for some older guys in the ring, and when I was about 14 I got shipped off to my dad. While I was there, I met this guy named Al [Cisneros]. He would eventually become the bass player and singer for Sleep. He had this band called Asbestosdeath, which was this dirge-y, Black Sabbath-y punk band. I wanted to play leads and do a bunch of crazy stuff, and they were like “No man, it’s not like that.” We’d go see these really great punk bands like Neurosis and the Melvins that were doing something new and cool at the time, and we got to open for guys like that. Eventually, we dropped the other guitarist and formed Sleep. And man, Sleep blew up really, really fast after that. I spent my 21st birthday in Amsterdam on tour, and before that we had done a tour in the States.

It didn’t last that long, though—why?

We made Jerusalem and then broke up. I’m an aggressive, competitive type of guy. I like a challenge. It’s a great attitude to have when you’re an athlete, but sometimes it’s bad when you’re a musician. I get that way to try and push the music to be the best that it can be, and if I blow you off the stage one night, that’s your problem. You should be doing that to me! [Laughs]

Then what happened?

So, six months go by and I start High on Fire. I met Des through a friend, and instantly clicked with him after we jammed. He’s one of those drummers that I know exactly what his playing is going to be like, and I think he feels the same thing. He wouldn’t have put up with me for this long if he didn’t. We’ve been working together for years and years, and we made kind of a business out of it. It’s like if you started a painting company or something. You might not get paid all of the time, but you believe in this one weird thing. For us, it’s that we play beautiful music together.

Snakes for the Divine is pretty aggressive— even for you guys.

This one is a lot more aggressive than the last one. The last one had its moments. Our bass player, Jeff Matz [formerly of Seattle hardcore band Zeke], wrote a lot more of the stuff than last time. He was a little bit shy about showing what he could do, thinking that he’d get shot down if he brought in a riff or two. I was like, “No, dude!” So he’d be down in the studio at 6 a.m., looping something in a delay pedal. I’d hear it and think, “Oh my god, dude, you’re really serious about this aren’t you?” [Laughs]

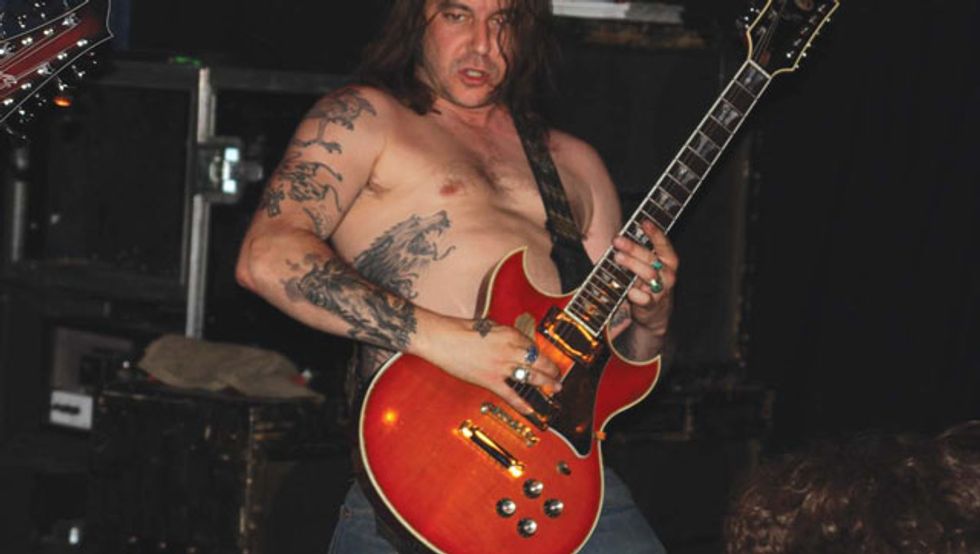

Matt Pike and hist custom First Act—which is a half-inch thicker than a Les Paul. Photo by Chris Kies. |

Did this record come together faster since you guys have been playing together for a while now?

No! Jeff, Des, and I sat around Oakland for eight months, just going down to the studio and pressing record. We started thinking about how we were going to get all of this on a record, and then we met Greg Fidelman [engineer for Johnny Cash’s American V and Slayer’s World Painted Blood]. We started playing him the stuff we had, and he told us that we had about four or five albums’ worth and that we needed to cut the fat. He thought we were going around in circles, just chasing our tail, and that we could make something great out of what we had. It was a good thing, because we’re so good at writing stuff together that sometimes we’ll just keep writing and writing if no one is there to yell “Stop!” or “You need to record that!” and “You need to hone in on one thing.”

You guys have played with some really talented bassists over the years, too.

We went through George Rice, our first bass player, and he was incredible. He just got sick of the touring, and he’s a lot like me. You know, he has to be out loud and a smartass all the time. Then we got Joe Preston [formerly of the Melvins and Thrones], recorded Blessed Black Wings, and asked him to tour. After a while, he said that he was sick of us and the huge amount of touring that we do, which is like nine out of 12 months a year. Who would want to do that, right? [Laughs] It really bummed me out when he left, because I love Joe Preston. Then, we found Jeff after touring with his band Zeke. Des and I said to each other after seeing him play “We need him in our band!” I felt guilty because I didn’t want to steal him from another band. It worked out though.

Was he the only candidate at that point?

I called Hank [Williams] III, who’s a really good buddy of mine. I said “Shelton, do you want to play on the album?” That dude’s making, like, five albums all of the time, so he was pretty busy then. He’s a big High on Fire fan but he said he wouldn’t feel right there. But then he said, “Jeff Matz”— the bassist from Zeke that Des and I toured with—“is looking for a band.” Des and I were stoked, and I called him up to come practice. He can play guitar exactly like I do, and he knew all the songs. About 50 to 60 percent of Snakes for the Divine was written by him, too. I told him “I’ll just put lyrics over your riff, I don’t even know what to say.” [Laughs]

So let’s talk gear for a bit. What are you using for the tour?

Basically, my main rig starts with a Soldano SLO. It was custom made for me by Mike Soldano, and it’s the best investment I ever made. They’re not cheap. I’m using it with a Marshall Kerry King head, which has a built-in noise gate. It runs with the Assault control, which adjusts the intensity of the channel. I use it in the right way, because there is no clean tone whatsoever in that amp.

Yeah, it’s hard to associate clean with Kerry King.

Dude, that head is so gnarly sounding. It’s the closest thing I could find to punching a guy in the face. [Laughs] I used to use a Green Matamp, an MXR distortion, and a power amp, and then I got a Soldano unit, one of the old purple ones. I really liked the way the extra tubes in the chain made a difference in the tone. So once I figured that out, running the Soldano into the Green Matamp, through another power amp and then a bunch of 4x12s, it was like, “I’m on to something!” So then I called Mike [Soldano] and said “Hey, man, I play in this band called High on Fire” and he said “Yeah, I know who you are!” He’s a big fan and he offered to make me an SLO, so I took him up on it.

What differences are there between that one and a standard SLO?

Pike's dual-amp rig of Soldano SLO and Marshall JCM800 Kerry King heads. Soldano settings: Preamp - Normal: 7, Overdrive: 11, Bass: 11, Middle: 8, Treble: 4.9, Master - Normal: 4.9, Overdrive: 4, Presence: 4 - Marshall settings: Presence: 8, Bass: 8, Mid: 0, Treble: 5, Master: 5, Preamp: 9.8, Gate: 5, Assault: 10. Photo by Chris Kies |

Nice, I like that pedal a lot.

I actually bought it to use for some Sleep reunion shows that we did a while back, and I ended up using it for High on Fire. It’s killer, like an old tape delay in this little box. It’s a great design. I don’t really need a bunch of pedals, just a little delay from time to time.

What are your thoughts on the Emperor cabs, and how did you get hooked up with them? I’ve been seeing those onstage a lot lately.

What are your thoughts on the Emperor cabs, and how did you get hooked up with them? I’ve been seeing those onstage a lot lately.We were in Chicago when I first heard one onstage with a band that we were playing with. I really liked the way that they sounded, so I got in touch with them, and they made me a batch. The Green 4x12s that I had been using for years were beaten up pretty bad by that point, so I needed to replace them.

How do they compare to the Green cabs that you had been using?

Well, they have higher-wattage speakers, but they still sound really thick. Actually, they sound really similar, but the wood they use is really thick and sturdy.

You’re also a big proponent of First Act guitars. Most people only know them for their entry-level guitars, but they make some very nice custom instruments.

Man, they’re just the coolest guitar company ever. Bill [Kelliher] and Brent [Hinds] from Mastodon told me about them first, then Kurt [Ballou] from Converge. I called up John McGuire and Jimmy Archey at the company, and we’ve had an awesome relationship ever since. They hooked up me and Bill up with our nine-strings at the same time.

The top three strings are doubled, like a 12-string, right?

Yeah. I was hanging out with Bill one night, and we thought about how cool it would be to have a nine-string guitar. We both called them in the same week, and they were a little pissed because we didn’t have a design. They told me that I had to design it. So I had to go to the drawing board, and I thought to myself, “So, I get to design it, and Bill gets to play it. Cool!” [Laughs] I always really liked those Yamaha SGs that Santana played years ago, but I wanted a thicker guitar. I’m a man, I’ve got man hands, and I’m a big dude, so I need some weight and durability—because I’m gonna throw it around and beat it up or whatever. So I had them make it a half-inch thicker than a Les Paul Standard. I wanted a baseball bat neck, because I wanted to have big-ass strings on it—I need to punish with it. The pickups are from Kent Armstrong, and are really strong.

What tuning is that in?

C–F–Bb–Eb–G–C, low to high. I have another tuning now, too, which I use for the song “Bastard Samurai” off of the new record. It’s Bb–F–Bb–Eb–G–C.

How long did it take you to get used to playing the nine-string?

It took about a month. The doubled high strings provide a natural chorus, like how some guys will use a chorus pedal to cop it, like Zakk Wylde.

Is that what you use to play the intro to “Waste of Tiamat” [from Death Is This Communion]?

Live, totally. Jeff plays a couple of different Middle Eastern instruments, and the Tambura is one of them. So when we recorded it, we had a bunch of different instruments sitting around. I originally wrote that part, then Jeff altered it and said we should have more Middle Eastern parts. Dirty hippy. [Laughs] After hearing it, I was like, “OK, you’re right man! I totally get it now.”

That’s kind of another example of how bands in this scene have achieved notoriety on their own terms—they tour on their own and live out of their vans. A lot of players think they need a huge record deal to get them going.

Yeah, I know. Record companies wash those people up and eat them alive. You’re doing alright one day, then the next thing you know you’re homeless and some guy is beating on you for money. If that’s what you want, then fine. It’s not like I’m gonna quit or something. But man, that’s what happens. And if anybody wants to fool themselves that this is all about being on the job…you fucking walk in front of that many people when you feel like shit, you’re hung over, you haven’t done yoga in a month [Laughs], and you’re gonna tell me how you’re going to perform all of the stupid songs you made up for yourself and that make everybody else happy? It’s not an easy task. Suck it up, because there’s no calling into work sick. I had to play with a 103-degree fever and just had throat surgery, and played an instrumental set. I was on, like, 20 Norcos! [Laughs]

There doesn’t seem to be this preconception of “making it” in this scene.

Well, you care about making it, but in the sense of living in the moment. I get in a van, I don’t want a girlfriend bitching at me, and I don’t want a boss bitching at me that I have to be somewhere at 5 a.m. I just want to be in the van, heading to a stage, and then ruling! And if I want to wake up someone in the band at one in the afternoon to party, then, goddamn, you better wake up and play some guitar. It’s the way it should be! And as far as the underground rock thing goes, everybody bringing it now is over 30. It’s the new 20.

You guys have worked really hard to get this far, and a lot of people don’t realize just how hard it is out there sometimes.

We all worked our asses off. And you know, it’s also great to be in a band where all three of us are really part of the creative process. No one wastes any time. We have a studio and we pretty much live down there. But even with that, the times that we can all play together don’t always line up. So, one of us will be down there recording, and then play it back later for everyone who wasn’t there. There’s a lot of “Hey, that sounded good, play that again—I have something for it.” At the same time, I can’t deal with record companies that want to give you a deadline. There is no deadline for High on Fire. We don’t put out shit—we haven’t put out a crappy riff on a record yet—and I do not have any plans to do that. If it takes time, it takes time. We couldn’t write an album in a month and be happy with it. If you could do that, fine. But that’s just not how it is with us.

Are you shocked at all the exposure you guys are suddenly getting?

No, I deserve it! I hate to be an asshole, but I really do think we deserve everything we can get. I mean, I don’t know one band that’s been in the trenches this long. We earned it, and we’re good. And we’re going to continue to get better. It’s just a matter of…well, I’m 37 years old now—how much longer am I gonna survive? [Laughs]

Matt Pike’s Gearbox

First Act Custom Shop nine-string

Soldano SLO head

Marshall Kerry King JCM800 head

Emperor 4x12 cabinets with Jensen JC12-70EL Electric Lightning and 80-watt Weber Ceramic Thames speakers

MXR Carbon Copy delay

Boss TU-3 Tuner

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)