In 2021, the Madfish label released a 35-CD boxed set with a 168-page hardcover book on John Mayall, then 87. Let that sink in. How many blues artists, living or dead, ever received that kind of treatment? What made John Mayall: The First Generation even more remarkable is that it only documented the British blues legend’s career up to 1974—at that point, 10 of his 55 years as a recording artist.

Robben Ford surely speaks for many, noting, “The guy has a major place in musical history for embracing, practicing, playing, and promoting the blues in England, and spreading what might have remained a small, cult music form in rural North America to the rest of the world.”

“He holds a position similar to Miles Davis in jazz for opening the door for a lot of deserving talent to be heard, allowing them to go on to brilliant careers.”—Robben Ford

Mayall, who died on July 22, at age 90, grew up in Cheadle Hulme, Cheshire, England. From beginnings with the George Formby banjo and ukulele how-to guide, he sustained a long, prolific career with few equals in blues. In the 2004 documentary John Mayall—Godfather of British Blues, he reflected, “The focus had always been on the road work, rather than hoping for some hit record.”

For better or worse, he was best known for the famous sidemen who passed through his band. As Ford says, “He was the mothering womb for a long line of incredibly influential blues guitarists. He holds a position similar to Miles Davis in jazz for opening the door for a lot of deserving talent to be heard, allowing them to go on to brilliant careers.”

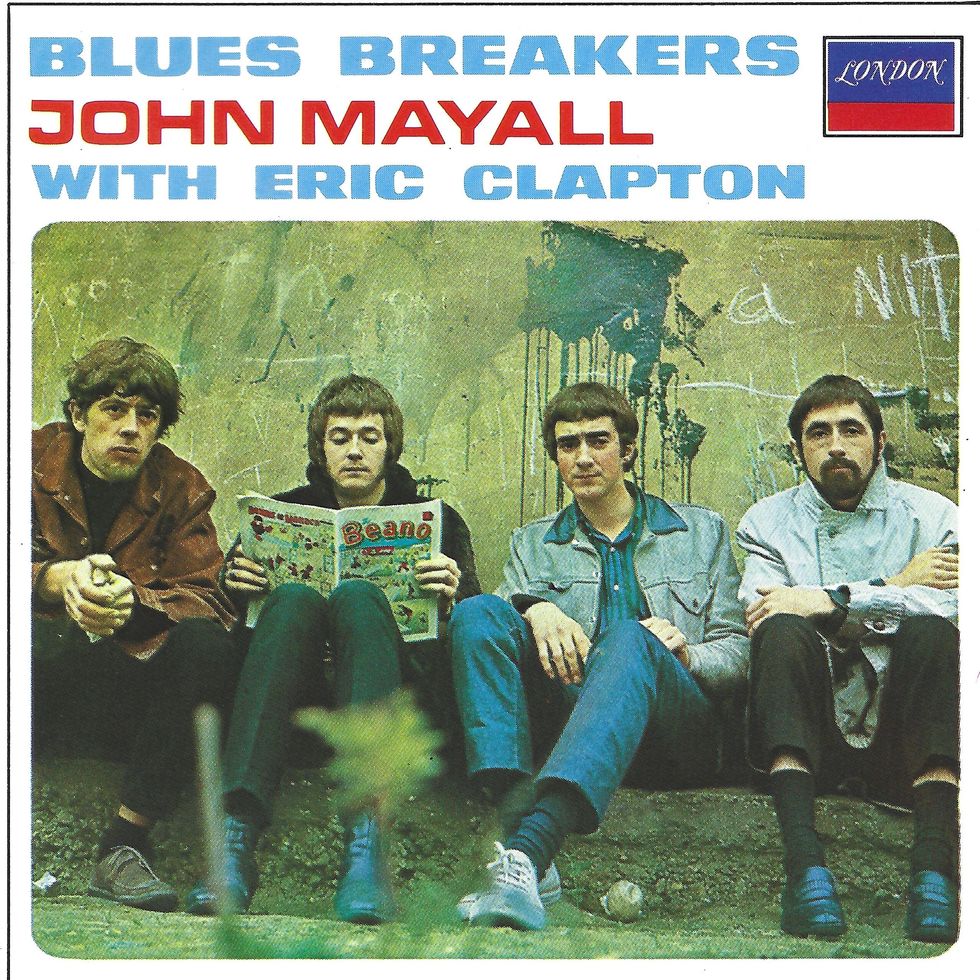

After the live John Mayall Plays John Mayall, with guitarist Roger Dean, 1966’s so-called “Beano” album ushered in essential appearances of Clapton, Peter Green, and Mick Taylor, on the Blues Breakers, A Hard Road, and Crusade albums, respectively

With the release of what’s often called the Beano album, after the comic book Eric Clapton is reading on its cover, both Clapton’s and Mayall’s legendary status were cemented. For at least two generations of players, Clapton’s version of the Freddie King instrumental “Hide Away” was a litmus test for emerging blues guitarists.

The drummer on Beano and its predecessor was Hughie Flint, who emailed, “Meeting John Mayall in 1957 was a special moment in my musical life, resulting in him becoming my mentor, sharing so much music. John was very much the bandleader, and knew what he wanted from his members. But with me, he let me play how I felt. I owe him so much, without which I would never have had a career in music.”

Clapton, Green, and Taylor all played ’Bursts, but their personalities were radically different. Clapton’s aggressive attack and unprecedented sustain from his Marshall JTM45 (later reissued as the Bluesbreaker amp) contrasted with Green’s pin-drop dynamics and Taylor’s long, unhurried lines. When “Clapton Is God” graffiti appeared, the “guitar hero” die was cast forevermore. Each was spotlighted on a Freddie King instrumental, giving their own spins on “Hideaway” (Clapton), “The Stumble” (Green), and “Driving Sideways” (Taylor). While all three “Kings” were influential, Mayall later pointed out that Eric owed the biggest debt to Freddie, Peter was into B.B., and Mick leaned on Albert.

But the succession of guitar greats didn’t stop there. After 1968’s Blues From Laurel Canyon, Taylor joined the Rolling Stones, and Mayall took a radical turn to an acoustic, drummer-less quartet. With saxophonist Johnny Almond and Jon Mark on gut-string, the live Turning Point (featuring the FM-radio hit “Room to Move”) was his best-selling album.

Still eschewing drummers, his next lineup featured Harvey Mandel and electric-violin wizard Sugarcane Harris on USA Union, with drummer Keef Hartley added for Back to the Roots, in ’71. For Memories, that same year, Mayall tapped guitarist Gerry McGee, a veteran of the Ventures, Monkees, and Delaney & Bonnie.

The years 1972 and ’73 produced Jazz Blues Fusion, Moving On, and Ten Years Are Gone, featuring guitarist Freddy Robinson, whose resume embraced Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, Quincy Jones, and others. With trumpeter Blue Mitchell, and saxophonists Clifford Solomon and Red Holloway, the albums went a long way in exposing some jazz greats to blues and rock audiences.

John would challenge you to go further as a musician and performer.”—Rick Vito

As Clapton said in the documentary, “He chose me for the way I play; he didn’t tell me what to play.” That was true for 6-stringers in subsequent lineups, including Hi Tide Harris, Randy Resnick, James Quill Smith, Cid Sanchez, Walter Trout, Debbie Davies, and Rocky Athas.

Rick Vito, whose five-album tenure began in ’75, recalls, “John would challenge you to go further as a musician and performer. When we were playing my hometown of Philadelphia, he said, ‘Okay, you’re starting the show,’ and shoved me onstage by myself! I improvised something of a blues suite and got a great response, followed by John and band joining me and starting the normal set, which was also always subject to change.”

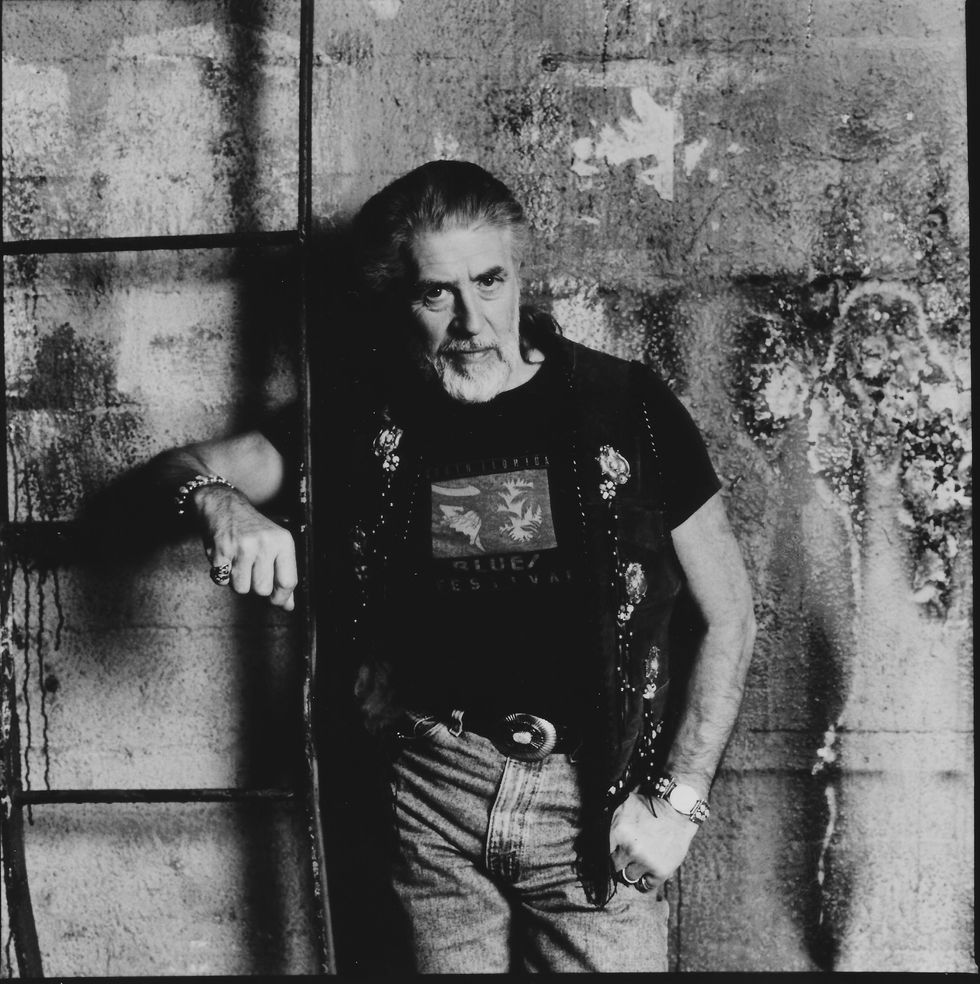

In 1968, Mayall retired the Bluesbreakers name for his band, but by the time this photo was taken, in 1995, he’d revived the moniker for a decade, and it would remain in use for the rest of his career.

Coco Montoya was actually a drummer, and had decided his music career was over prior to an impromptu jam. “I started playing guitar at 13, but it was secondary. In ’84, I played at a jam session where John heard me. The Bluesbreakers reunion with Mick was ending, and I got the call. Clapton was a hero to me, and I tried to emulate him and the others as much as I could; I thought that was the job. John took me aside and said, ‘Look, where’s that guy I saw at the jam session? You’re trying to sound like Eric. You’re not Eric. Don’t forget the first law of the blues: interpretation.’ In doing that, he freed me up from trying to be people that I could never be. John never let anything deter him, which helped me a lot in my solo career.”

After Buddy Whittington opened for John in Dallas in ’92, his phone rang the following year, and he was a Bluesbreaker for 15 years. “Most of the time, John would give you ‘about enough rope to hang yourself,’ meaning just play what you feel. If he didn't like where it was going, especially in the studio, he would stick his head in the doorway and say, 'Take this another way’—but that wasn't very often.”

Carolyn Wonderland came onboard in 2018 and played John’s last show in 2022. “It was such a musical education, as well as how to be a bandleader. He gave me board tapes of about 80 songs from different eras, and every night would be a different set; he never wanted it to be the same. And that was the same with the songs. When it came time for your solo, he’d push you until there was some spark. It’s frightening, jumping off the high dive, but it was so freeing, and he was right there behind you, ready. He made everybody reach inside to find out what your inner voice is. It’s like the graduate school of the blues that you never want to graduate from.”

John Mayall - Room To Move (Live)

John Mayall delivers a fast-paced rendition of his sole radio hit, 1969’s “Room to Move,” which originally appeared on the album The Turning Point.

Although his talent scout abilities often overshadowed his own contributions, constant components were the bandleader’s distinctive high vocals, authoritative piano and organ, harmonica in the Sonny Boy Williamson tradition, and quirky guitar, typically slide—often on homemade axes using Burns and Fender parts.

“When it came time for your solo, he’d push you until there was some spark. It’s frightening, jumping off the high dive, but it was so freeing, and he was right there behind you, ready.”—Carolyn Wonderland

Also, his songwriting expanded the repertoire, with songs such as “Have You Heard” and “The Laws Must Change.” “His voice and harmonica playing were unique and, for me, his greatest gifts,” says Ford. “But, just as important, as a composer he wrote some serious, classic blues that will live on with his recordings.”

For championing the blues, Mayall was awarded Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in 2005. In 2016, he also received an overdue induction into the Blues Music Hall of Fame, and equally about-time recognition came this year with his induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, alongside his British blues forebear, Alexis Korner.

In his liner notes to A Hard Road, Mayall wrote, rather dramatically, “I accept that I’ve unwittingly hurt a lot of people who’ve known me. I’ve few friends left, and now the only thing to live for is the blues.”

That was on his third album, when he was 33. Thirty-five studio and 33 live albums would follow, and he’d live to be 90. Maybe it was hard, but his bandmates would tell you it was also a joyous road.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)