Tom Crandall was the first person I met in the vintage-guitar industry, when I wrote a profile on him for Acoustic Guitar magazine back in early 2018. In mid February of that year, I visited his shop, TR Crandall Guitars—then in New York’s East Village, now on the Lower East Side—and spent three hours chatting with him about his work as a luthier and playing some of the instruments in his collection. (I had some unconfirmed flu symptoms, and, by so carelessly breathing in his general direction, passed the sick onto him right before he went on a trip to Mexico with his now-wife, Renée. Miraculously, he forgave me for this.)

I’ve brought my own guitars to Tom’s shop a few times since then, and when I took on the task of writing this article on the history of the Gibson J-45, I was looking forward to another opportunity to connect.

“Do you know George Gruhn in Nashville? Mark Stutman in Ontario? John Thomas, the guy who wrote Kalamazoo Gals?” I ask in advance of our conversation, listing some of my other interview subjects, previous and planned. Tom knows them all, and they all know each other, as well as the rest of the established names in the vintage business. (It makes it feel small, which it kind of is.)

We gossip a bit, and I feel as though I’ve been welcomed into the coven of vintage-guitar repair pros and historians. Tom shares that, in his current inventory, he has the earliest known J-45 from the Gibson banner era (more on that later). He hands it to me, and with a single strum I feel affirmed in why I’m writing this in the first place. And so, the following is the result of my conversations with two performers, a producer, an author, a documentarian, and three middle-aged and elder statesmen of guitar repair in North America on the story behind one of Gibson’s most beloved and ubiquitous acoustics.

NYC-based luthier Tom Crandall, owner of TR Crandall Guitars on the Lower East Side, has the earliest known J-45 currently in his inventory.

Photo by Kate Koenig

“What fascinates me about the guitars is the evolution in their design, the haphazardness of their build. I’ve become very knowledgeable in the morphology, for lack of a better word, of the J-45,” says vintage-guitar repairman and historian Mark Stutman. We’re talking on the phone as he drives to work at his shop, Folkway Music in Waterloo, Ontario. When it comes to vintage-guitar repairpeople, Mark’s a bit on the younger side—having just turned 50—and he claims that he probably won’t have much to add to what historian George Gruhn, my first interviewee, had to say. He then proceeds to share an encyclopedia’s worth of detail on Gibson guitar history—with remarkable accuracy.

Mark first explains that the J-45, which entered into the Gibson lineup in 1942, was made in the image of its predecessor, the J-35, and that the idea for the J-35 was built upon Gibson’s Jumbo model, introduced in 1934. A 14-fret acoustic with a sunburst on every side and a lower-bout width of just over 16", the Jumbo was about a half-inch wider than the standard dreadnought, and Gibson’s biggest flattop at the time. It had sloped shoulders on its upper bout, with a greater curve than the more squared-off shoulders of a traditional dreadnought. Martin had released the first dreadnought, the Model 222, in 1916, but the body shape didn’t really catch on until their later introduction of the D-18 and D-28 in 1931.

Country singer/songwriter Kacey Musgraves plays a 1957 J-45, which she’s named “Janice,” at the Royal Oak Music Theatre in Royal Oak, Michigan, in 2019.

Photo by Ken Settle

“I’m sure Gibson introduced their Jumbo guitar to compete directly with Martin’s dreadnoughts,” says Tom, back at his workshop. “I think that’s really what it was. It was starting to take off, and Gibson and Martin were competitors in the flattop world.”

Both brands were racing to move away from the production of the then-more-prevalent smaller-bodied guitars to meet the shifting demands of the zeitgeist. As Stutman says, “[That was what] people wanted, as the whole cowboy-singer, Jimmie Rodgers, railway-switchman-entertainer thing happened in the States. They needed a guitar with a lower-frequency response so that their yodeling could be heard on top of it and not be fighting with the guitar.”

The original Jumbo was listed at $60. “It was just about the height of the Great Depression, so it didn’t sell well, because nobody had 60 bucks to spend on a guitar in 1934,” Stutman comments. In response, Gibson scrapped the Jumbo just over two years later and replaced it with the J-35, which sold for $35. The J-35 had the same outline, scale length, and 14-fret neck design as the Jumbo, but to manage the reduced sale price, Gibson trimmed back the Jumbo’s accents, removing the sunburst from the back, sides, and neck, as well as the pearl headstock inlay, back binding, and high-end tuners.

The interior of a J-45 (left) and a J-35 (right)—the former with two tone bars and the latter with three.

The first J-35s were built with three tone bars—the braces placed at a slant within the bottom half of the X-bracing—which made them powerful and cutting. But because the market was asking for guitars that were more bassy and warm, Gibson decided to reduce the tone bars to two by 1940. And that wasn’t the only adjustment that was made.

“They changed the angles that the X makes under their top,” Stutman says. “And about a year later, they changed that X angle again, and they put scalloped bracing in. They changed the size of their bridge plate. They messed around with how thick they wanted the top to be. As a result, J-35s that we find today vary tremendously from guitar to guitar and very much from year to year.”

Then, in 1942, Gibson debuted the J-45 and J-50, both the same model, but with a sunburst and natural finish, respectively. They priced the J-45 at $45, and charged $5 more for the J-50 (Stutman guesses because they had to use higher quality wood under a natural finish). The original design featured a mahogany neck, back, and sides, a spruce top (first Adirondack, later, Sitka), and a Brazilian rosewood fretboard and bridge. They also kept the same shape as the J-35. “The last of the J-35s were made in the early ’40s,” Stutman shares. “By 1941, a J-35 is kind of the same guitar as the J-45, but most of the world doesn’t know that.

“Even out of necessity, in 1944, they discovered a way to make a guitar that today is one of the most sought-after, great-sounding guitars in the world, out of mostly indigenous hardwoods.” —Mark Stutman, Folkway Music, Waterloo, Ontario

The year of the J-45’s release, Gibson also made a few modifications to their acoustics, replacing the more “lumpy-looking” prewar pickguard with the smaller teardrop pickguard. They designed a new headstock shape, where its sides were concave rather than straight. And, cue the fabled “banner era”: “[Gibson guitars] from ’42 through ’45 have a yellow, silkscreen, script Gibson logo on the peghead and a decal banner that says, ‘Only a Gibson Is Good Enough,’” shares vintage-guitar historian George Gruhn, owner of Gruhn Guitars in Nashville, over the phone. “And there are collectors who pay extra for the guitars from that period.”

This vintage sunburst-finished model displays the classic J-45 look.

The release of the J-45 happened in the midst of global calamity, coinciding with the U.S.’s entry into World War II. A change in ownership occurred later during the war when, in 1944, Gibson was purchased by Chicago Musical Instrument Company (CMI). (Ted McCarty was later appointed president in 1950.) And, as young male luthiers were required to comply with the nation’s draft, several women were instated at Gibson in their place. “I have on the record the president of Gibson at the time testifying in front of the war production board that his company was being run almost entirely by women,” says John Thomas, the author of 2013’s Kalamazoo Gals. Women not only did much of Gibson’s administrative work, but were responsible for producing at least 25,000 guitars—many of which are highly coveted today. That aside, the period also presented manufacturing limitations due to the federal government’s wartime rationing of various materials.

“They had written regulations as to what percentage of metal they could have in proportion to the weight of the instrument,” explains Gruhn. “Musical instruments were very, very highly regulated, as was almost everything in manufacturing during World War II.”

“Epiphone came out with a slogan, ‘Good Enough Is Not Enough’—and Gibson dropped that banner like a hot potato.” —George Gruhn, Gruhn Guitars, Nashville

This meant that Gibson did not have the necessary supplies to make their adjustable truss rods, which they’d been using since 1921 and patented in 1923. The solution was to return to their previous method of installing a triangular wooden block of maple, roughly an inch-and-a-half wide, in the neck near the headstock. “They did that for strength, but it would also make the neck way bigger,” says Stutman.

“It was variable, but many of the necks [from those years] are 1 3/4" wide. And the depth at the first fret—I’ve measured some that are almost 1.1" deep. By comparison, a ‘big’ electric guitar neck, like on a ’59 Les Paul, might be 900 thousandths deep.”

Yet, even more impactful than the shortage of metals was the decreased availability of woods. “It was just hard to get rosewood from Brazil during World War II when there were German U-boats all over the Atlantic,” Stutman points out. “And more importantly, for Gibson, their mahogany supply was running low, ’cause it came from the same place.”

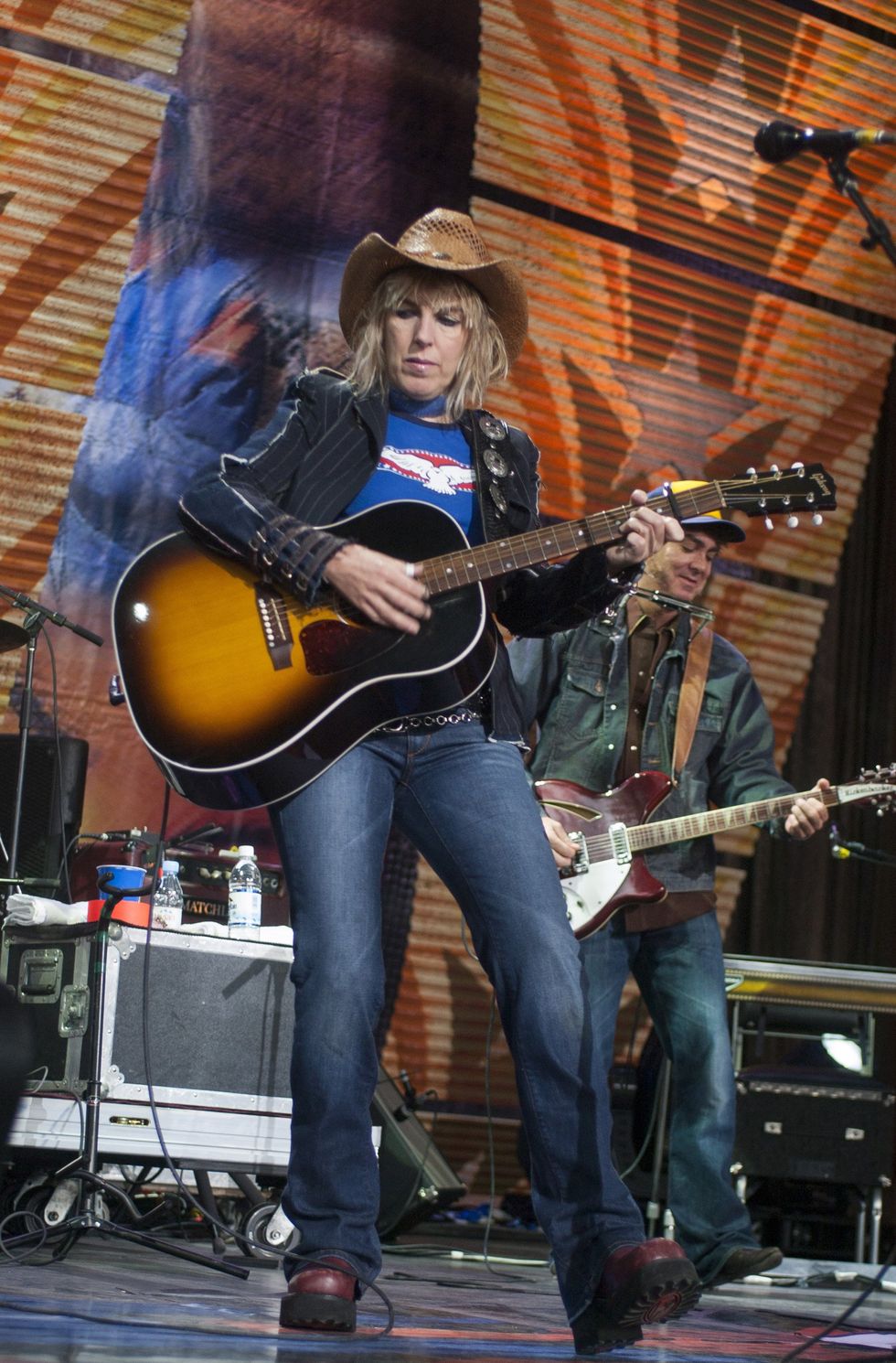

“I think that’s the magic to her sound,” Lucinda Williams’ guitar tech Justin Bricco told Premier Guitar of Williams’ most played J-45 in her 2014 Rig Rundown.

Photo by Ebet Roberts

This led to inconsistencies in J-45 features. During that time, Gibson began using multiple pieces of maple—or even a combination of different woods—to create necks, as it was also harder to acquire individual pieces of a larger size. “It could be a 5-ply neck for strength,” comments Gruhn.

“From 1943 and ’44, sometimes you find fretboards and bridges made out of gumwood instead of Brazilian rosewood,” Stutman elaborates. “So you get these really interesting J-45s from the late banner era. You might find a guitar that has a maple back and sides, a maple neck, a gumwood fretboard and bridge, and a spruce top—that’s almost entirely built of North American woods, which is pretty darn cool. Even out of necessity, in 1944, they discovered a way to make a guitar that today is one of the most sought-after, great-sounding guitars in the world, out of mostly indigenous hardwoods. Anyways, what happens is, the war ends, metal comes online again, Brazilian rosewood, mahogany. It’s all back in 1946-ish.”

The banner era had also come to a close by 1946. Gruhn adds, “I’ve been told that one reason for that was that Epiphone [which wasn’t acquired by Gibson until 1957] came out with a slogan, ‘Good Enough Is Not Enough’—and Gibson dropped that banner like a hot potato.”When the war had ended, “this little blip of really exciting guitars from 1942 to 1946 that have all sorts of unique characteristics and interesting tone and feel and uniqueness and charisma … those go away,” Stutman shares. Gibson standardized their specs across their models, though at first some J-45s were still made with parts left over from the banner era. But by 1947, the design was fully solidified, and the J-45 as we now know it was born. “The sound of a J-45 that we’re all familiar with, that thing that we all love about the J-45, that strummer, singer/songwriter, country guitar kind of thing, is a sum total of how it’s built with that light scalloped bracing of the Sitka top in particular; a 1 11/16" nut; mahogany back and sides; that short scale; and the style of neck carve. All that stuff adds up to having a J-45 be a J-45. Then, from ’47 to ’55, not very much changes with it.”

“This is the tool of the storyteller. This is the tool of the songwriter. You want an acoustic guitar—you hit the J-45 button.” —Ted Wulfers, J-45 documentarian

There was, however, a significant change in 1956—the issuing of the adjustable-height bridge with a ceramic saddle, labeled the J-45ADJ, for “adjustable,” which was sold, at first, as a second option for the consumer. “And then they became a standard feature,” Tom says, showing me one of the J-45ADJs he has in his inventory. “So this is an adjustable bridge. It’s kind of heavy. It’s got big brass pieces underneath. And because of all that weight and this sort of disconnect, you can hear a compressed sound.” (I play it, and, for the record, hear exactly what he’s talking about.)

Then, there was another less-than-desirable modification in the early ’60s, as told by George Gruhn: “Around ’63 is when the J-45 had those horrible, hollow plastic bridges rather than a wood bridge. It didn’t function, but it would look like the actual adjustable bridge was bolted through the bridge plate.” Those bridges ended in 1970—coinciding with when the Panama-based conglomerate Ecuadorian Company Limited (ECL) acquired CMI, then renamed themselves as the Norlin Corporation. “Gibson has not used them since, but now there’s a lot of variations of J-45 historic reissues.”

“It’s a very personal thing,” Aimee Mann said of her J-45 to Paste in 2010. “You want to play a guitar that’s an extension of you.”

Photo by Tim Bugbee/tinnitus photography

Most of my conversations with Stutman and Gruhn are focused on the J-45’s early history, so I venture further to fill in the blanks of what happened with the guitar in the decades following. Over a Zoom call, I spend about an hour absorbing J-45 lore and geeking out about guitars in general with Ted Wulfers, a filmmaker who has been putting together a documentary on the history of the J-45 for the past several years. In the process of making the film, he’s interviewed 180 people from 14 countries. “We’re going to be expanding to about six more,” he says.

“In 1968, they switched the J-45 to the square shoulder, and that remained until 1984, through the Norlin era,” Wulfers explains. Gibson added a volute to the neck, to compensate for the weakness of the area where the neck becomes the headstock. But, “People kind of got sick of them, and they went out of fashion in the ’80s.”

Due to waning popularity, Gibson briefly discontinued the J-45 in 1982. But in ’84, they brought it back with the slope shoulder—in very low production. They also introduced some new finishes, including a whiskey burst and an amber burst. Eventually, in the ’90s, as Wulfers shares, Gibson fully restored their production of J-45s, and reinstated the ’40s-style slope shoulder and tuning pegs to the design. “I think that’s one of the reasons why they went out of fashion in the ’70s and ’80s—they weren’t playing as good as the guitars from the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s. They came back into fashion once they started making the guitar like the older versions,” he laughs.

“A great guitar is the tipping point of being held together and being pulled apart. So, I’ve always had a theory that my favorite guitars are really on a fulcrum’s edge of that.” —John Leventhal

Yet, as Tom suggests, it took a few more years before the J-45 was reinstated to its earlier popularity. “I’ve owned quite a few J-45s, and I was buying them in the ’90s for like $800, $900. I always thought, ‘Wow, these things are so undervalued.’ So I would buy them, fix them up, maybe sell them for 1,200, 1,300 bucks. Then somehow, in the early 2000s, they started to catch on again.”

But what about the J-50, if they’re truly identical models beyond the finish? “I think a lot of the reason why the J-45 has become so popular is because they’re gorgeous,” says Stutman. “Gibson sunbursts, back then, were exquisite. They just got it right. And even though the J-50 was [originally] more expensive, and today it’s a way more rare guitar, the J-45 is still more valuable. That’s simply because people love a good-looking sunburst. And when you pick up a J-45, you feel like you look the part.”

A closer look at the two-tone-bar interior construction of a classic J-45.

Photo courtesy of TR Crandall Guitars

According to Tom, his friend John Leventhal—the six-time-Grammy-award-winning producer, musician, and recording engineer—has long been a fan of J-45s and J-50s. “He just came out with his first solo record at 70 years old, and he used the J-50 that he got from us on a lot of those cuts,” he says.

When I connect with Leventhal on the phone, he strikes me as a straight shooter. “I really don’t know what the hell you’re talking about,” he quips, when I ask him if he has an audio-engineer interpretation of the J-45’s physics (a question inspired by my personal scientific bent).

He offers, instead, “Why Gibsons are different from other guitars, I couldn’t really say. ’Cause basically, the physics of all these things are more or less the same. A great guitar is the tipping point of being held together and being pulled apart. So, I’ve always had a theory that my favorite guitars are really on a fulcrum’s edge of that.

“Whatever it is about the construction of the J-45,” Leventhal continues, “is that really good ones have what I would call a strong fundamental tone in which the overtones don’t really get in the way or don’t confuse the sonic output of the guitar. I have my own recording studio, and I notice everybody’s pretty happy when they play these things.”

❦

“How many guitars do you have?” I ask Steve Earle over Zoom. (Steve is a frequent visitor at TR Crandall; coincidentally, Tom receives several texts from the country-rock guitarist while we’re chatting in his workshop.) Steve’s just labeled himself a “degenerate collector,” saying that among the instruments he owns is every Gibson flattop except for a J-100, an L-2, and a Dove.

“I just did the inventory. I think it’s 187 instruments, counting banjos and mandolins. And I do count ’em.”

Earle’s been playing Martins for several years now, but his time with J-45s and J-50s goes way back. “I hitchhiked up to Nashville when I was 19, you know, to do what I do,” he shares. He had a Martin D-18 at the time, which he traded for an Alvarez Yairi when no one in town could repair the Martin’s bowed neck. “When I got to Nashville, I was the only guy with a Japanese guitar sitting around in a room with a bunch of Gibsons and Martins, and it started to embarrass me. So the very first check I got when I signed my publishing deal, I went down to George Gruhn’s and bought a 1956 J-45 for $250. That’s about what they went for in 1975.” He later traded it to Jerry Jeff Walker for $500 and a ’65 J-50ADJ (whose hollow bridge had been replaced with a solid one). “That was my guitar for years. I recorded part of [1986’s] Guitar Town on it.

“So, the very first check I got when I signed my publishing deal, I went down to George Gruhn’s and bought a 1956 J-45 for $250.” —Steve Earle

“I own one now,” he says. “I’ve got a really good 1950 J-45. I had this belief that that’s like, the perfect year for a J-45, ’cause Ray Kennedy owns one. All my acoustic tracks on [1997’s] El Corázon were recorded on his guitar because when I got outta jail [in1994, after a 60-day stint], I didn’t have anything. The one I have now, I bought from [NYC luthier] Matt Umanov. It belonged to Adam Levy before me.” He says the one he’s used the most, however, is Kennedy’s.

Grace Potter - "Mother Road"

❦

Country-rock guitarist and songwriter Grace Potter has a signature Gibson Flying V, but she’s also been an ardent J-45 player for years. “A J-45 was actually the first guitar I ever bought,” she tells me, when we connect over the phone after Wulfers points me in her direction.

“I was 19 and I walked in cold to a music shop in upstate New York called Dick’s Gas, Guns, and Guitars. In the back was this incredible guitar shop that felt like a novelty in the moment.”

With $860 to her name, she made a deal with the owner, who let her make a partial down payment on the $900 guitar. “It was a 1999, and I bought it in 2002,” she continues. “The second I picked it up, it transported me to the 1940s and an open window of potential. It sang so beautifully. And I just remember the feeling of the body of the guitar against my chest, curling my body around it, and feeling like I just met a long lost aunt that I didn’t know I had. And that’s when I started writing songs on guitar, immediately.” Naming the first two albums she produced with her band the Nocturnals, she adds, “Every song from Nothing but the Water, and some of the songs on This Is Somewhere, were written on that J-45.”

❦

On my call with Wulfers, we’ve taken a detour from the J-45 subject, and I’m now enthusiastically telling him about the specs on my Washburn and Taylor acoustics. He’s into it, but helpfully brings it back to the main topic—on which he’s clearly, passionately fixated.

“It was fresh off the factory floor, but the second I put it in my hands, it transported me to the 1940s and an open window of potential.” —Grace Potter

“The J-45 has the bass, but that midrange, too; it cuts, but it allows the human voice to shine,” he asserts, “whereas a couple other guitars and styles of the Gibson line, of the Martin lines and others—they cloud the vocal. Sometimes, when I’m working with an artist here in my studio and they have my J-150 or a big Guild or something, I’m just like, try the J-45. And they go, ‘Oh my god, everything sounds better.’ Well, you know, sometimes it is the guitar.

“This is the tool of the storyteller. This is the tool of the songwriter,” he continues. “If you want delay, you hit a delay pedal. If you want reverb, you hit a reverb. You want an acoustic guitar—you hit the J-45 button.”