In late April, Burlington, Vermont-based luthier Adam Buchwald visited the Sphere in Las Vegas. The immersive, much-hyped venue cost $2.3 billion to construct, and to be sure, it’s a sight to behold.

The exterior of the building, touted as the largest spherical structure in the world, is covered in 580,000 square feet of LED displays. The interior, capable of 16K resolution, adds another 160,000 square feet of displays. It’s perhaps the most exciting music venue in the world, and on four consecutive evenings in April, Buchwald watched legendary Burlington band Phish play it.

Buchwald, 46, has been a Phish fan since the ’90s, so to see his hero Trey Anastasio, the iconic frontman and guitarist of the band, playing on the hottest stage on earth, accompanied by the sort of psychedelic visual atmosphere befitting the band, was a thrill. But for Buchwald, there was an even bigger, personal treat: On three of the four evenings, Anastasio played an acoustic guitar Buchwald had built.

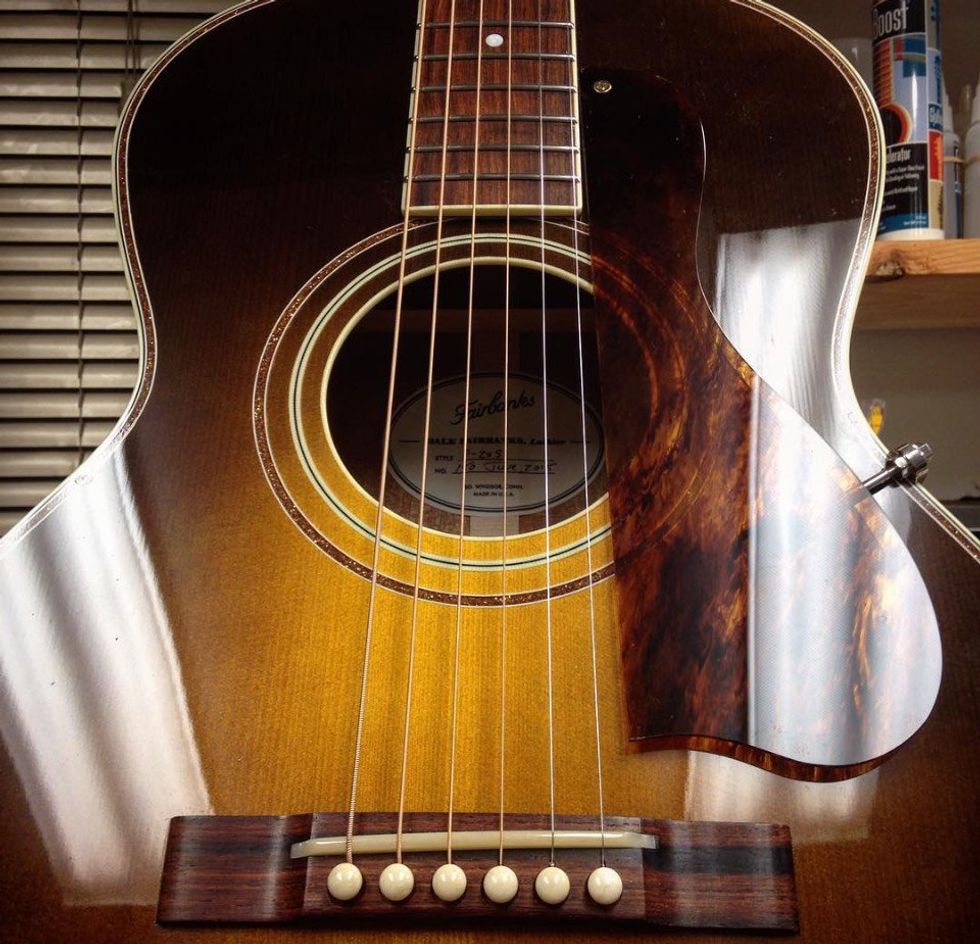

The dreadnought was made with gorgeous, hand-picked “mother of curl” Koa back and sides. The top and bracing are 100-year-old German spruce; the neck is 75-year-old mahogany. The appointments are stunning: holly binding and trim, Waverly titanium tuners, black pearl inlays indebted to American artist Roy Lichtenstein. The instrument was commissioned by Phish keyboardist Page McConnell after he and Buchwald crossed paths in a Burlington paddle-ball group. Buchwald, who owns and operates the guitar brands Circle Strings and Iris Guitar Company alongside luthier-supply outfit Allied Lutherie, was honored to take up the task.

There are plenty of high-end 6-strings on the market from trusted legacy brands like Martin, Taylor, or Gibson, but Anastasio chose an instrument from an independent guitar builder in a small northeastern city to bring to Vegas. So how did Buchwald’s acoustic end up centerstage at the Sphere? You can find the answer in a red, aluminum-sided 15,000-square-foot shop space in an industrial spur on the edge of town, near Burlington’s airport.

Principal luthiers Adam Buchwald and Dale Fairbanks joined forces back in 2019, and along with a team of talented guitar-builders, like CNC expert Will Hylton, they now design and build all their instruments under one roof.

“I never wanted to put my name on the headstock.” —Adam Buchwald

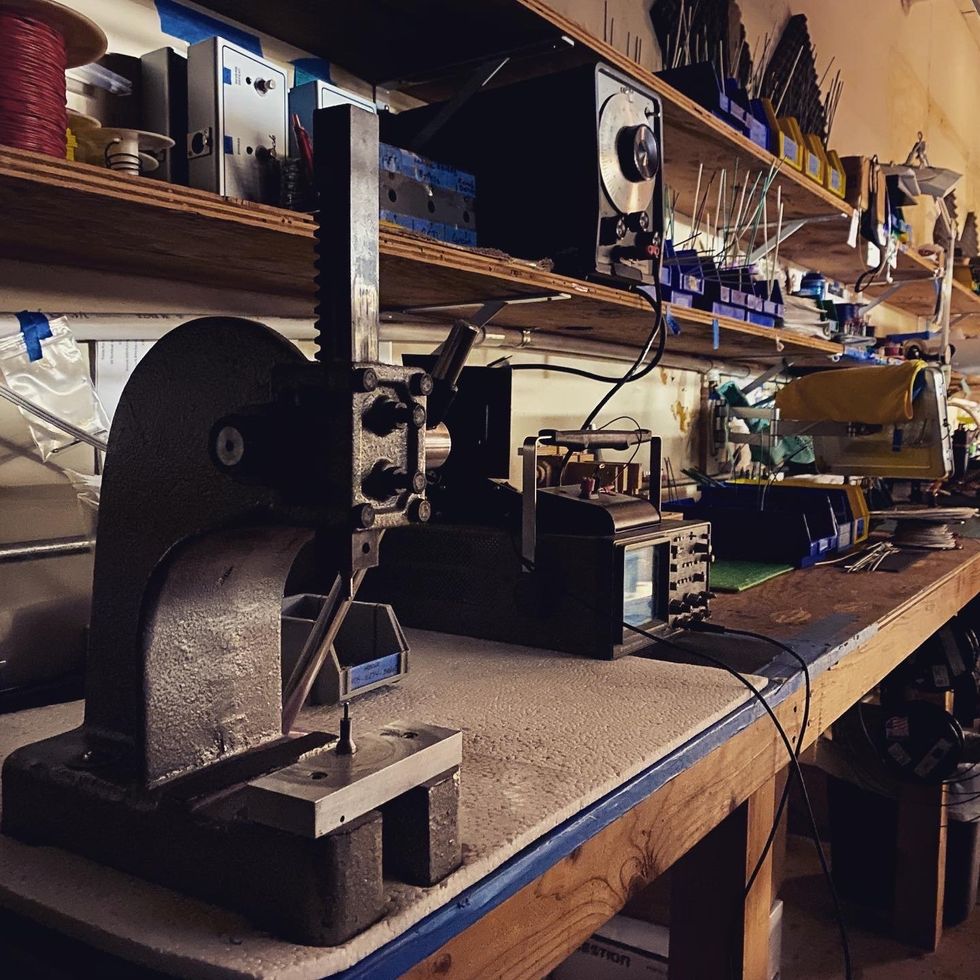

The sprawling, labyrinthine single-level space, which takes up part of an old auto-repair shop, is an acoustic guitarist’s dream. Four distinct brands live under the one roof: Circle Strings, Iris, Allied, and luthier Dale Fairbanks’ Fairbanks Guitars. On a video call, Buchwald walks me through the building. We snake from the front office through to the shop floor, where racks of wood planks tower over Buchwald on every side. There are molds where the wood is bent into shape, and nearby are hulking custom-made CNC machines (including a Haas VF-2 and a Laguna M2). A 3D printer sits alongside them. Further along, there’s a finishing area complete with a spray room. “Smells like delicious chemicals,” quips Buchwald when he pokes his head around the room, where bodies and necks hang like slabs of meat in a butcher shop.

In an adjoining production area of wide workbenches, someone labors on a neck for an Iris guitar; Fairbanks, headphones on, plugs away on one of his own creations. A sanding room juts off from the main floor, where a mask-clad worker smooths out the top of an unfinished body. Through another set of doors is the setup workshop, where head of setup Storm Gates is hunched over a stringless, caramel-colored dreadnought. Finally, there’s the recently opened showroom and store, Ben and Bucky’s Guitar Boutique, where Iris, Circle Strings, and Fairbanks acoustics hang on the wall for people to try and buy. There’s a snappy collection of amps for sale, too, plus other odds and ends.

Buchwald moved into this space in 2018, after years of building his Circle Strings guitars in New York, Connecticut, and Vermont. Since he was 10 years old, Buchwald has been obsessed with guitars. His parents were constantly driving him to local guitar stores around his hometown of Bedford, New York, to check out “the best of the best,” he says, and after high school he went to the University of Vermont to study music theory and composition. He wanted to be a performer, but when he needed money back in New York after school, he took up a spot in his father’s manufacturing company, Circle Metal Stamping. “I worked on machines and saw how a factory worked and got experience using my hands and all the tools and everything in front of me,” he explains. Around that time, Buchwald began tinkering with his guitars and had a realization: “Wow, I could actually build these things.” He had all the tools he needed at his disposal. After a guitar-building course and apprenticeship at a New York City repair shop, and a job running the repair shop at Brooklyn’s RetroFret Vintage Guitars, he started to build his own acoustics.

Buchwald always drifted toward acoustic music: Bluegrass, newgrass, classical, and jazz were his stomping grounds, so it followed that he’d build acoustic 6-strings. Around 2005, he started his own company, Circle Strings, a nod to his family’s business. “I never wanted to put my name on the headstock,” he notes. In 2008, he, his wife, and their newborn baby moved north to Vermont, where he taught lutherie at Vermont Instruments, and worked at Froggy Bottom Guitars for a spell. He built his Circle Strings guitars out of his garage before moving into a proper shop space in Burlington next to his friend, electric guitar builder Creston Lea.

Orders for Buchwald’s guitars began to take off, and before long, his boutique acoustics were fetching more than $5,000. Even so, he’s not terribly precious about his work. “I can sit here and try and bullshit my way around this whole conversation and tell you I’m tap-tuning and voicing tops,” he says. “I’ve studied all that shit, learned different methods and people’s theories on brace carving and how they’re played and how thick they are. I just feel like we came up with a formula that works, and we just stick to it. To me, it’s more about picking out the woods and how I’m piecing them together. That’s my way of thinking about voicing.”

Obviously, Buchwald’s approach works. Phish’s Anastasio is far from the only convert. New York-based fingerstyle guitarist Luke Brindley has been playing Circle Strings acoustics for nearly a decade, and he just got a new one this year—a 6-string OM-size made from German spruce and Brazilian rosewood. “I’m not sure how Adam does it technically or whatever,” says Brindley. “I know he’s an expert on woods and obviously a musician himself, but ever since the first guitar I played of his, I felt like it perfectly suited my “voice.” I don’t know. It’s just like a perfect combination of the craft and then a little bit of magic and intuition.”

Phish’s Page McConnell commissioned this Circle Strings acoustic as a gift for bandmate Trey Anastasio, who recently took it to the stage for three nights at Las Vegas’ Sphere.

Photos by Shem Roose

In 2018, Buchwald launched Iris Guitar Company, which would produce more affordable, less decorated models for players who couldn’t shell out for Circle Strings instruments. The following year, he took another leap. He bought Allied Lutherie, a wood and supply company based in Healdsburg, California, that was up for sale, along with all of their materials, for a fair price. The owners gave Buchwald a good deal, including interest-free payments over the next few years. The lumber was shipped from coast to coast, and Buchwald and his team in Burlington loaded their score of tonewoods, plus a boatload of other materials, into their shop. Now, Buchwald could sell guitar-building materials to any and all comers, and Circle Strings and Iris instruments would be produced, nose-to-tail, under one roof.

Soon, so would Fairbanks guitars. Dale Fairbanks loved the old acoustic guitars he had when he was young, but he had no idea how the hell people managed to build them. How could luthiers force the wood to contort and hold the shape of a guitar’s body? Answers came in the form of William Cumpiano’s 1984 book Guitarmaking: Tradition and Technology. It became Fairbanks’ bible, but eventually he needed to go beyond the page, so he drove up to see Massachusetts luthier Julius Borges and badgered him with questions as long as Borges would stand it. Fairbanks’ 1933 Gibson L-00, which he bought in his early 20s, has always been his benchmark for acoustic excellence, and after 10 trial-and-error runs of guitars, he started selling his creations around 2009. He’s never been without an order since then.

For years, Buchwald and Dale Fairbanks had talked about joining forces to share overhead, production costs, staff, even ownership. When Buchwald bought Allied, he pitched Fairbanks again: Come up to Burlington and build guitars under the same roof, with a load of wood at our fingers. Fairbanks and his wife wanted a change from central Connecticut, so they packed up their house and headed north to Burlington in November of 2019. Soon, the two luthiers were settling into a new, expanded shop space complete with a large spray and finishing booth, and Buchwald’s newly launched Iris line promised to keep a steady revenue stream while they produced their more time-consuming, intricate instruments. Like Tom Petty sang, the future was wide open.

Fairbanks’ made-to-order acoustics, like this gorgeous tobacco burst F-20 model, can cost more than $10,000. From the start, Fairbanks has been committed to uncompromising quality.

Then the pandemic hit. Offices shut down, layoffs rocked working people, musicians went silent, and budgets shrank as business ground to a halt. Millions went into survival mode. For a time, it seemed like the purchase of Allied might nosedive into disaster. Buchwald was saddled with a small forest’s worth of wood, and it seemed like no one had the money to put him to work on it. If things got bad enough, reasoned Buchwald, he could sell off the wood at least. But surely no one would be lining up to buy high-end acoustics for a while. “It was terrifying,” says Buchwald. “I’m like, ‘Fuck, I just bought this business, I just rented this shop, I just got all this equipment, and then the pandemic happens.’”

“Now, I have to give up control to other people with my guitars, which took some getting used to. Luckily, we have a really good crew.” —Dale Fairbanks

Luckily, Buchwald’s fears didn’t come to pass—if anything, the opposite happened. “Everybody bought wood, everybody bought guitars, and the businesses took off,” says Buchwald. He was able to pay off Allied, expand the Iris lineup, and invest in new equipment and people to pad out the operation. The Iris models, quicker to produce while still being high-quality guitars, paid the bills so he and Fairbanks could spend more time and care on their custom projects.

While some elements of Fairbanks’ builds have been changed by the new production facility, they still retain key Fairbanks qualities: They all have glued dovetail necks rather than rather than the bolt-on mortise-tenon joints Buchwald prefers, and Fairbanks still builds most of them himself after the body is assembled, although he’s also adopted some of Buchwald’s techniques.

For Fairbanks, this type of collaboration has been a lesson in letting go. He had worked alone as a one-man operation building his Fairbanks guitars for 15 years before shacking up with Buchwald, and suddenly, other hands were working on his instruments. “Now, I have to give up control to other people with my guitars, which took some getting used to,” he says. “Luckily, we have a really good crew. So many talented people have come from different parts of the country to work here.”

One of those people is Will Hylton, the “chief CNC wizard” at the complex. (Hylton had to reschedule our first interview time because he was working on a replacement guitar neck for Keith Richards’ ES-335. “It’s the dream come true, really,” he says. “One of the reasons I got into guitar building to begin with is like, ‘Man, I want to build guitars for my favorite guitarists.’”) Hylton says that with Iris, he and his colleagues have endeavored to apply the Toyota Production System—a set of lean manufacturing principles developed by the Japanese automaker in the decades after the Second World War—to prioritize efficiency in their processes, while safeguarding the more time-consuming parts of the Circle Strings and Fairbanks builds. “With the higher-end guitars, there’s more problems to solve and things to work through that are pretty fun, depending on the mood,” says Hylton, who designs and programs the CNC cuts. “Iris is more my engineer side, while the Circle and Fairbanks stuff, I get to appease my artistic muse.”

With four different companies under one roof, Hylton’s days can vary. “It could be working on figuring out a way to speed up a process in the production realm, or it could be working on a $3,000 inlay, or it could be fixing a machine,” he explains. “There’s always a big curve ball.”

Burlington musician Zach Nugent, who played with Melvin Seals and JGB and helms the Grateful Dead act Dead Set, swears by his Fairbanks acoustic. “There are a lot of really high-end boutique guitars that are great on paper, but just don’t move me,” says Nugent. “Each brand new guitar feels like it’s got a hundred years of gigging and amazing stories in the sound. Every person that I introduce to this guitar, I say the same thing. I know how stupid and whatever this sounds: ‘This is the best guitar you’ll ever play.’

At the heart of the Burlington operation—and the seemingly magical acoustics produced there—is the vast collection of old, rare woods that Buchwald purchased from Allied Lutherie and various other sources.

“I know $2,000 is a lot of money for a lot of people, especially for a guitar. But once you get a better guitar and you sound better and you play better and it feels better, you bond with it, and you’ll get better as a musician.” —Adam Buchwald

“I don’t know if Dale is just stopping in and making guitars for the humans for a little bit, but something really special is going on with those guitars.”

None of the guitars that Buchwald, Fairbanks, Hylton, and the rest of their colleagues build are what you’d call “cheap.” Iris guitars still cost upwards of $2,200. People say all the time that the “affordable” line isn’t all that affordable. Buchwald doesn’t mind. “I say, ‘The only way to get it done cheaper is to have it made overseas,’” he says. “It won’t play as well, it won’t look as good, they won’t use as nice materials, and you won’t be supporting focused, dedicated craftsmen like what we have here. I know $2,000 is a lot of money for a lot of people, especially for a guitar. But once you get a better guitar, and you sound better and you play better and it feels better, you bond with it, and you’ll get better as a musician.”

That belief in the irreplaceable value of a carefully made guitar is probably part of the reason why Circle Strings, Fairbanks, and Iris are unlikely to ever take up entire display walls in your local music stores, like other acoustic brands do. “I don’t necessarily want to make 500 guitars a week like Taylor does,” says Buchwald. “I want to keep the quality of it as high as possible and limit the supply so there’s always some demand. I like having guitars that are sought-after.”

Earlier this year, an investor proposed a plan that would have doubled the production and output at the Burlington warehouse. It “scared the living day-lights” out of Buchwald. “I knew that the people that I hired to do this work would look at me after two months and say, ‘Fuck this, this isn’t what we want to do, we’re not some huge manufacturing company,’” he explains. “If we can expand, we’ll expand slow and steady.”

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)