On May 1 and 2, torrential rains buffeted Tennessee, Kentucky, and Mississippi. More than 13 inches of rain caused the Cumberland River to rise 52 feet and spill over into Nashville. The Red Cross put the death toll at 24, and property damage is virtually incalculable. Beyond the human suffering and loss, some of the most heart-wrenching destruction was wreaked upon Music City’s historic and irreplaceable artifacts—many of which were stored at Soundcheck studios. The facility took on four feet of water and became the epicenter of the worst mass destruction of guitars in modern musical history.

A collection of Keith Urban’s guitars—including a vintage SG, Les Pauls, Teles, and a Gretsch G6199—hangs out to dry inside Soundcheck. Photo by Jim McGuire

A collection of Keith Urban’s guitars—including a vintage SG, Les Pauls, Teles, and a Gretsch G6199—hangs out to dry inside Soundcheck. Photo by Jim McGuire"Beware of Snakes!!!” That’s what a sign taped to the door of Soundcheck studios reads. This is good advice for anyone in the music industry, but they mean it this time. It is Friday morning, six days after the Cumberland River surged hard and fast into this flat industrial district of Nashville. And as if the toxic slurry of mud, chemicals, and mystery brown stuff left all over the floors wasn’t dangerous enough, the early responders to this massive complex of rehearsal halls, repair shops, and storage lockers encountered venomous, slithering reptiles angry about being beached inside.

People are checking in with employees at a table inside the door. Most media have been stopped at an outer gate. Soundcheck management, understandably, doesn’t want local TV news cameras and lights pointing at the musicians as they pull the corpses of cherished instruments out of their sodden cases and trunks. I have been added to the client list as a volunteer proxy for John Jorgenson, a globally admired veteran of country, rock, and jazz. He is on tour with his gypsy jazz quintet in Europe, doing his best to keep a calm head and coordinate an unprecedented, unplanned evacuation operation from thousands of miles away.

I am with Jorgenson’s stepson, and our mission is to empty his locker and get his instruments and amplifiers to a designated dry-out and repair facility where Jorgenson’s acclaimed luthier, Joe Glaser, can administer emergency care—or last rites—to a collection of stringed instruments of inestimable personal and musical value.

The darkened halls and lockers are bustling with top-flight Nashville session musicians and their guitar techs. Pedal-steel guitarist Bruce Bouton is grieving the loss of his collection of vintage amplifiers. Nearby, country guitar kingpin Brent Mason is taking stock of his losses. Wearing blue surgical gloves, he photographs a prized ’65 Stratocaster that comes out of its case looking ghostly pale and slashed with cracks. At a loading dock, the road crew for country band Rascal Flatts is rolling case after case from multiple storage lockers onto trucks, stopping for photos and analysis by insurance adjusters.

Jorgenson’s locker gives away the story of what’s happened here. The water line is clearly visible in the particleboard walls— about three and a half feet from the floor. Inside, it’s a pathetic sight. Guitar cases are jumbled on the ground as if they’ve floated, shifted, and then sunk like dead submarines. A Marshall amp cabinet looks like it’s been airbrushed with an ash-colored residue. The most important guitars are stored vertically in a road case, their bottoms well off the ground, but it’s pretty clear they were submerged up to their necks and are now sitting in the humidified dark on saturated shag carpet. Nothing in the place smells good, but when cases start opening the stench of mildew and death permeates the air.

For the finite population of vintage and important guitars left in the world, the Nashville flood of May 1 and 2, 2010, may be the most costly natural disaster in history. Guitar experts can think of no other mass wipeout that compares. Hurricane Katrina tragically swamped the homes and instruments of an inestimable swath of musicians in America’s most musical city not nicknamed Music City. But whereas New Orleans is chiefly a city of horns and drums, Nashville is a guitar town. And some of the most carefully tended and cultivated guitar and stringed-instrument collections in the world were here in Soundcheck.

“It is really massive. Every day you hear about more stuff,” said Dave Pomeroy, president of the Nashville chapter of the American Federation of Musicians. “It’s really hard to back up far enough to see this in perspective. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say this is an unprecedented loss. Because these instruments owned by the top musicians are the cream of the cream. Somebody said it’s the equivalent of the Louvre flooding. These guys were working musicians. So [their instruments] were tools, but from a financial and esoteric standpoint, one of these Stratocasters is worth how many new ones? It’s not possible yet to put a monetary value on it. But in terms of vintage, playable instruments, it’s probably the biggest wipeout in the history of modern music.”

A cracked and mildewed vintage Strat being aired-out as part of a massive salvage project headed up by respected Nashville luthier Joe Glaser. Photo by Mark Montgomery

Nashville’s most famous guitar dealer, George Gruhn says, “I feel like there’s been a big death in the family. We have lost a piece of our heritage. This is not just a personal loss for the owners. This is a loss for all of our society. Because these things, just like Stradivari or Guarneri violins made in the 1600s, are still played today and can be played later. They go from generation to generation, and these are things worth going from generation to generation. It’s like losing a Van Gogh painting.”

Gruhn’s landmark shop on Lower Broadway was not flooded, but there were hours on Sunday, the second day of rain, when it was touch-and-go. As the Cumberland crept to within two blocks, the staff moved all the instruments that were on stands from the showroom to the second floor—a precaution that turned out to be unnecessary. Ed Beaver, who had a repair shop inside the Soundcheck complex, was not so fortunate. He spent the weekend after the flood tearing his cozy facility apart, ripping out workbenches and memories.

“If I let my mind wander as a luthier and guitar person, I could probably sit down and quit and just cry,” he said. “The history that is in Soundcheck is beyond belief. It is not the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It’s not the Country Music Hall of Fame. It is the working tools of musicians that have come out of Nashville for decades. Soundcheck was the Fort Knox of instruments in Tennessee. To an instrument guy, it’s like watching Joplin die or Hendrix die. Lennon. We had guitars out there that have that much history—that much influence in the industry.”

As it happened, and by the cruelest twist of fate, one particular collection at Soundcheck was specifically curated to be just that important. The Musicians Hall of Fame was established by long-time Nashville dealer Joe Chambers, a man so dedicated to the Nashville guitar and musician legacy that he used to keep a parking place permanently reserved for Chet Atkins by his shop doors. He spent considerable sums of his own money to grow a collection of iconic American instruments and artifacts to be the core of a hall of fame that has already inducted the Nashville A-Team, the Wrecking Crew, and the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section. Chambers renovated a building just south of Broadway, across a wide parking lot from the Country Music Hall of Fame, and opened in 2006. Less than a year ago, the city determined he was inside the footprint of a massive new convention center, and bought him out via eminent domain. Lacking a long-term home for the museum’s pieces, Chambers was forced to move nearly all of the instruments he’d collected to Soundcheck about a month before the flood.

Peter Frampton’s badly cracked three-pickup Les Paul gets some TLC. Photo by Mark Montgomery

His wipeout was staggering. A 1960s Stratocaster owned by Jimi Hendrix will never be the same. The top of a cherry sunburst Gibson Les Paul Deluxe played by Pete Townsend on the Who’s Quadrophenia tour is riddled with cracks [See “Opening Notes, pg. 22]. And the upright bass played by Floyd “Lightnin’” Chance on Hank Williams’ last recording session collapsed into a sickening pile of wood and wire. “If we had been able to work out an agreement with the city, we would have been sitting high and dry,” Chambers told The Tennessean. “We wouldn’t have lost a guitar pick.”

Meanwhile, the list of working guitarists affected by the Soundcheck flooding reads like some kind of royal order. Besides Brent Mason and John Jorgenson, Brent Rowan had at least a dozen road cases full of guitars and gear. Acoustic guitar star Bryan Sutton is determined to restore a damaged 1930s Gibson L-00 that had been passed from his grandfather and father down to him. Dave Roe, Johnny Cash’s last bass player, lost two uprights and 25 electrics, including the 1970 Fender Precision that he used on the majority of his sessions.

And Soundcheck was not merely the province of sidemen. Vince Gill reportedly had more than 60 carefully collected guitars impacted, including a D’Angelico and some vintage Strats. Brad Paisley was about to start rehearsals for this year’s tours, so nearly all of of his instruments and his band’s entire road rig were affected. Peter Frampton had vast amounts of gear underwater, as did John Fogerty, John Hiatt, and rock journeyman Steve Farris.

“It’s funny,” says Farris, “I survived the Northridge [Los Angeles] earthquake. I survived ripped off guitars in LA. And I was reminiscing yesterday with [Lynyrd Skynyrd drummer] Michael Cartellone about years ago when I took guitars and stuff to his apartment because fire was coming up the hill in Woodland Hills and he lived over in Sherman Oaks. And I never put guitars all in one place, but I thought what the hell, I’ll move away to my ranch and put them all in [Soundcheck]. And Mother Nature finally caught up.”

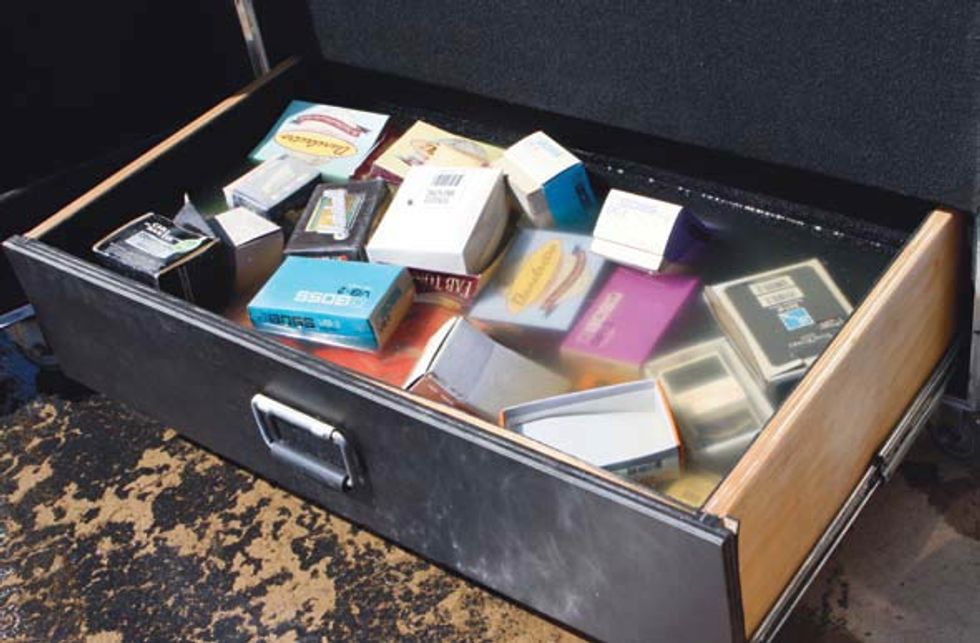

A drawer full of waterlogged pedals—including models from Carl Martin, Marshall, Danelectro, and Boss. Photo by Mark Montgomery

In fact, she took a toll on instruments and gear all over Nashville. The Gibson manufacturing facility took water and had to be shut down for an undisclosed length of time. (Fortunately, the Gibson Custom Shop was not flooded.) Home and professional studios suffered, like the one owned by Americana and rock producer Ray Kennedy. Kennedy says he saved his guitars but that he lost some vintage recording gear. And the inundation at the riverside complex housing the Grand Ole Opry House and the Opryland Hotel simply defied belief. The Cumberland River overtopped a dike built after a 1975 flood of what was then Opryland USA. By the time it was over, two feet of water covered the Opry stage and soaked the lockers and offices of the Opry administration and musical staff. Musicians and employees waded into the water in the dark to remove instruments from the Roy Acuff Museum and backstage areas. The losses there—potentially devastating—have not been disclosed. Corporate owner Gaylord Entertainment imposed media silence on employees until restoration efforts and a full accounting had been completed.

When stories of this flood are told years from now, however, most of the heartbreak and loss will be symbolized by Soundcheck. Opened in 1993 by Glenn Frey of the Eagles, and his roadie Bob Thompson, Soundcheck Nashville was an offshoot of their Third Encore rehearsal space in Los Angeles. About six years ago, Ben Jumper, a long-time road production manager, purchased Soundcheck and began an ambitious expansion. The place became a small town of product reps, microphone dealers, case builders, and a concert-video production company. It worked because it is incredibly convenient to the freeway. It’s also on a floodplain.

George Gruhn has been outspoken in his opinion that Soundcheck was the right business in the wrong spot. “There is a reason [that land] was never developed for housing. It floods! I think it was poor judgment on a lot of people’s parts.”

In his defense, owner Ben Jumper can point to the fact that even though the ground around Soundcheck has seen a few inches of water in decades past, his buildings’ floors are four to five feet above the ground, and this was at least a 100-year flood. “I feel I’ve done the best I could to protect everything in Soundcheck,” he says. “You cannot anticipate an event of epic proportion. My father—my grandfather—never saw anything like this in Nashville. It’s something you don’t anticipate or don’t believe would ever happen. Obviously we were all wrong. And it did happen. And I don’t know that I have ever been through a tragedy like this and I hope I never am again.”

Left: A soggy, sagging acoustic is one of the many flood-damaged instruments that will never be played again. Right: One of the lucky few salvageable acoustics at Soundcheck being dried out with an industrial fan. Photos by Mark Montgomery

Left: A soggy, sagging acoustic is one of the many flood-damaged instruments that will never be played again. Right: One of the lucky few salvageable acoustics at Soundcheck being dried out with an industrial fan. Photos by Mark MontgomeryJumper’s clients seemed to be satisfied and even impressed with Soundcheck’s response to the flood. He secured two large dry-out facilities, and over three days company trucks and roadies moved tons of gear to the spaces where it could be spread out and dried at a proper pace. Guitar techs set up a kind of field hospital, where they disassembled the electrics, soaked the electronic parts in WD-40, and bagged them for rebuilding later. Guitars were laid out everywhere. Keith Urban’s guitars and banjos dangled from a ceiling by their headstocks as if from some hideous hanging tree.

Glaser shuttled between several facilities, working on guitars owned by Urban, Gill, Jorgenson, and others. Sizing up the overall damage on the Saturday of the recovery, he said, “It’s like any disaster. There’s been a lot of really pleasant surprises and a lot of discouraging damage, which we expected to see. The acoustics have fared worse than the electrics, because any instrument put together with water-soluble glues is tending to come apart. The acoustics are generally built out of boards that were bent into shape, and these are straightening out again. But there are some surprising survivors, particularly in old and valuable instruments. The irony is that, for the last 10 or so years, there’s been quite an industry in making new guitars look like old guitars, and this flood has done more of that than everybody’s careful expertise combined.”

John Jorgenson’s travel back from Europe was a nightmare in itself. Starting with the troublesome Icelandic volcano, a rash of problems got him home more than a day late. By then, we’d opened his guitars, emptied them of water, and put them in Glaser’s care. Some we’d delivered to his home so he could see them as soon as possible. None of those prized instruments had been spared damage, and some were complete wipeouts. Two mandolins—a pre-war Gibson A style and a custom-built John Monteleone—had more or less exploded. A rare Höfner guitar in the shape of Paul McCartney’s famous bass had mold inside it. And one-of-a-kind presentation pieces, including a custom Gibson Casino with artwork based on the Beatles’ animated Yellow Submarine film, had taken serious damage to its bindings and its previously pristine finish.

Some of John Jorgenson’s guitars—including a Fender Tele, a G&L ASAT, an Ovation uke, and his signature Fender Strat—with parts removed and bagged for safekeeping. Photo by Jim McGuire

“It was pretty horrifying,” Jorgenson says about finally facing the instruments and vintage amplifiers he’d collected and cared for so assiduously over so many years. One particularly hard-to-take loss was a 1961 Gibson Les Paul SG. “I bought that on time payments when I was 15 years old, and I’ve had it my whole life. It was really the first really good guitar that I ever bought, and I played it forever. It’s a great guitar. And I’ve had the original case with it and I’ve taken care of it. Guitarists will know those have the original PAF pickups, which are super valuable now. And I’d never done anything stupid like change them out! And to see it cracked and with rusty pickups just really kind of broke my heart.”

It’s a hurt that perhaps only guitar players and lovers can fully understand. Jorgenson and many others spoke of being caretakers and curators for their instruments. They technically own them, but they said they felt more like they were holding them in trust for future players and the future of music. Pretty much everyone spoke respectfully and emotionally about the many lives and homes that had been lost in the flood, but at the same time, fine instruments have a life force of their own.

“I know they’re just objects. They’re tools,” said Jorgenson two weeks after the flood. “But when somebody put in the time that it took and the energy and creativity to build those— that’s someone’s energy in it. And then it had a significance in the careers of other artists. That’s kind of the overwhelming part. It felt like my history was just being ripped away. I know that’s not true, but that’s what it felt like.”

Gone But Not Forgotten

By Thomas Scott McKenzie

Luckily, the type of immense guitar destruction seen in Nashville is a rare occurrence. Guitar catastrophes don’t happen often, and in the rare event they do, they can be related to industrial tragedies, natural disasters, or more mysterious causes. Here are just a few sad examples.

Mosrite Factory Fire, 1983

California guitar maker Semie Moseley came to prominence in the 1950s and ’60s with his unusual-shaped guitars and multi-necked instruments. His Mosrite brand is perhaps most well known for being played by the Ventures and Johnny Ramone. After a series of setbacks, Moseley re-located his factory to Jonas Ridge, North Carolina. In late 1983, the factory caught fire and burned extensively. Lost in the blaze were not only the production models being built, but also Moseley’s personal collection of triple-necked instruments.

Hurricane Katrina, 2005

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in August 2005, instrument loss was the least of anyone’s worries. More than 1800 lives were lost and tens of billions of dollars in property damage occurred. Unlike in the Nashville flooding, there weren’t any single warehouses or storage facilities affected. Instead, the hurricane’s devastation was so widespread that putting a single dollar amount on the loss of instruments is almost impossible. “For months, people were bringing in instruments to save,” says Dave Newman of International Vintage Guitars in New Orleans. “But we’re guitar technicians, not miracle workers.” Music Rising, a non-profit organization founded by producer Bob Ezrin, U2 guitarist the Edge, and Gibson chairman and CEO Henry Juszkiewicz, provided 2700 replacement instruments to affected musicians in the short term after the catastrophe. Since then, the group has restored gear to tens of thousands of people.

Southern California Wildfires, 2008

Just about every year wildfires threaten the cities and suburbs of Southern California. With the high numbers of musicians in the area, it is in some ways a pleasant surprise that more wildfire-related guitar loss doesn’t occur. However, the Los Angeles Times did report the sad story of Roger Heath’s experience in 2008. A 20-year resident of Twin Lakes, California, Heath thought he had more time before the blaze would reach his home, but then he was suddenly surrounded by smoke and gray ash. He managed to save his 1959 Les Paul but lost 24 other instruments when his house burned to the ground.

Gretsch Factory Fires, 1973

In 1973, a disastrous fire halted production at Gretsch’s Boonville, Arkansas, factory for three months. Another fire would follow in December of that year. The Booneville chapter of Gretsch’s storied history is largely forgotten by most connoisseurs of the brand and is even downplayed with a bit of embarrassment in the company’s own annals. This is due to what is widely regarded as a period of questionable quality control during the company’s Baldwin years. The Baldwin Piano company bought Gretsch in 1967 and moved guitar production from New York to Arkansas. As QC slipped, Chet Atkins withdrew his endorsement and Baldwin eventually shut down guitar production in 1981. To this day, rumors persist that disgruntled employees sabotaged operations during the Baldwin era.

Robert Keeley Electronics Fire, 2009

On a cold afternoon in January 2009, employees at Robert Keeley Electronics were hard at work on their popular pedals when a fire broke out in the company’s Edmond, Oklahoma, factory. “It was a scary moment for everyone,” says company vice president Jacob Adams. “All of us were out there watching, and we didn’t know what the future held for us. We didn’t know how bad the fire was going to be, what all we were going to lose.” The firm lost the bulk of its inventory, as well as a large supply of vintage parts. A year and a half later, the company has moved into a brand new facility and is back to full capacity—with more employees than before the disaster.

By Thomas Scott McKenzie

Luckily, the type of immense guitar destruction seen in Nashville is a rare occurrence. Guitar catastrophes don’t happen often, and in the rare event they do, they can be related to industrial tragedies, natural disasters, or more mysterious causes. Here are just a few sad examples.

Mosrite Factory Fire, 1983

California guitar maker Semie Moseley came to prominence in the 1950s and ’60s with his unusual-shaped guitars and multi-necked instruments. His Mosrite brand is perhaps most well known for being played by the Ventures and Johnny Ramone. After a series of setbacks, Moseley re-located his factory to Jonas Ridge, North Carolina. In late 1983, the factory caught fire and burned extensively. Lost in the blaze were not only the production models being built, but also Moseley’s personal collection of triple-necked instruments.

Hurricane Katrina, 2005

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in August 2005, instrument loss was the least of anyone’s worries. More than 1800 lives were lost and tens of billions of dollars in property damage occurred. Unlike in the Nashville flooding, there weren’t any single warehouses or storage facilities affected. Instead, the hurricane’s devastation was so widespread that putting a single dollar amount on the loss of instruments is almost impossible. “For months, people were bringing in instruments to save,” says Dave Newman of International Vintage Guitars in New Orleans. “But we’re guitar technicians, not miracle workers.” Music Rising, a non-profit organization founded by producer Bob Ezrin, U2 guitarist the Edge, and Gibson chairman and CEO Henry Juszkiewicz, provided 2700 replacement instruments to affected musicians in the short term after the catastrophe. Since then, the group has restored gear to tens of thousands of people.

Southern California Wildfires, 2008

Just about every year wildfires threaten the cities and suburbs of Southern California. With the high numbers of musicians in the area, it is in some ways a pleasant surprise that more wildfire-related guitar loss doesn’t occur. However, the Los Angeles Times did report the sad story of Roger Heath’s experience in 2008. A 20-year resident of Twin Lakes, California, Heath thought he had more time before the blaze would reach his home, but then he was suddenly surrounded by smoke and gray ash. He managed to save his 1959 Les Paul but lost 24 other instruments when his house burned to the ground.

Gretsch Factory Fires, 1973

In 1973, a disastrous fire halted production at Gretsch’s Boonville, Arkansas, factory for three months. Another fire would follow in December of that year. The Booneville chapter of Gretsch’s storied history is largely forgotten by most connoisseurs of the brand and is even downplayed with a bit of embarrassment in the company’s own annals. This is due to what is widely regarded as a period of questionable quality control during the company’s Baldwin years. The Baldwin Piano company bought Gretsch in 1967 and moved guitar production from New York to Arkansas. As QC slipped, Chet Atkins withdrew his endorsement and Baldwin eventually shut down guitar production in 1981. To this day, rumors persist that disgruntled employees sabotaged operations during the Baldwin era.

Robert Keeley Electronics Fire, 2009

On a cold afternoon in January 2009, employees at Robert Keeley Electronics were hard at work on their popular pedals when a fire broke out in the company’s Edmond, Oklahoma, factory. “It was a scary moment for everyone,” says company vice president Jacob Adams. “All of us were out there watching, and we didn’t know what the future held for us. We didn’t know how bad the fire was going to be, what all we were going to lose.” The firm lost the bulk of its inventory, as well as a large supply of vintage parts. A year and a half later, the company has moved into a brand new facility and is back to full capacity—with more employees than before the disaster.