Randy Parsons abandoned the guitar after years of playing in high school and college. He quit, assuming he had no future in music, and ended up working for the city of Bellevue, a suburb of Seattle. But then, one day, he received a vision of sorts that sent him on a journey toward custom-made guitars made of exotic and unusual materials—in addition to interactions with some of his childhood heroes.

Page playing the Strolling with Bones flattop Parsons made for him. It features Kasha-inspired bracing and a secret button to light up the interior, and its neck, fretboard, back, and sides are all of ebony. |

That journey came after a period of serious introspection mixed with sweat and hard work, a blend of the esoteric and do-it-yourself know-how. Despite starting with zero training as a luthier, he has built a business with five different shops and celebrity clientele that includes Jimmy Page, Joe Perry, Jack White, and Sammy Hagar. He works out of his main Seattle shop, which is run by five women—three of whom are luthiers—and he also has Parsons Guitars repair shops in four Washington-area Guitar Centers.

We recently spoke to Parsons about his history, using bones in guitars, the significance of the number 333, and the fusion of mystic vibes and good old-fashioned hard work.

How did you get into luthiery?

I had given up the guitar. I had been that kid in high school that everyone thought would be a rock star. But deep down, after much soul searching, I just knew it wasn't going to happen. I gave it up in my 20s and went a different direction altogether. I don't even think I owned a guitar. It was the furthest thing from my mind. But when I was 28 years old, I was taking a shower one day and I got hit with this vision. It was so strong: I saw myself making guitars for my idols—like Jimmy Page—and having a business and doing the whole thing. It was just a fraction of a second, but it was like an instructional video inside my head showing me how to approach this new life. I remember getting out of the shower—I was shaking—and I couldn't dry off fast enough. I got in my little Jeep and went down to the hardware store. I had about 300 bucks and I spent it on a band saw, woods, some glue. I had no idea what I was doing, but I was just like, “This is it—this is my life," and there was no stopping me. It just felt so right and I just went for it.

|  |  |

| The Strolling with Bones acoustic Parsons built for Page features a Sitka spruce top with Kasha-style bracing and an ebony neck (left) and an embedded silver “spell coin" the luthier has had since childhood (center). “I figured it couldn't hurt," he says. Bones' interior is supported by four flying braces tied together with waxed leather (right). | ||

You have jokingly said you almost flunked high school shop class. So your wood skills weren't exactly outstanding. How did you go about the process of learning to build guitars?

I locked myself in my basement for two years. This was before YouTube, so there really wasn't a lot of information out there. I just started cutting wood and trying to invent how guitars were made based on what I knew. I would buy some crappy guitars and take them apart, but I was just a madman. I think I made over 100 guitars in those two years in my basement. They were crappy and I didn't even finish a lot of them, but I was on this mission. I told myself, “I need to spend two years and learn this craft the best I can." That began this serendipitous journey where the right things, the right materials, and the right people just came into my life at the right time.

Who were some of the folks that helped you?

Well, there was Boaz Elkayam. He's this underground gypsy guitar maker and he's well known in the classical world. He would travel from country to country and build guitars with small tools. I was so obsessed with building guitars that I decided to build some flamenco guitars, and I thought, “If I'm really going to learn how to make these, I need to learn how to speak Spanish." A Spanish instructor introduced me to Boaz, and it began this friendship. Boaz actually lived with my wife and me for a year. We would stay up at night and drink wine and talk about guitars. The most important thing he taught me was when he pulled out this Mexican knife he carried around with him everywhere and said, “This is all you f-ing need. Learn to make guitars with this and this is all you will ever need." And that began my relationship with low-tech tools. And he was right—technology really gets in the way. If you can make your guitar with hand tools, then you're better off. Famous people will contact a major company and say, “Hey, I had this idea…" and the manufacturer says, “Geez— no, our computerized machines aren't calibrated to do that." But I can do anything, because I can make a guitar with a hand knife. I can just conjure up a way of approaching any request. In my shop, there are no CNC machines, there are no Plek and fret machines. There's none of that crap. It's all just small tools.

|  |  |

| Left: Another view of Bones' top underside reveals a personalized inscription on the bass-side bout, as well as bracing inscriptions like “Thoracic Spine" and “Right Clavicle." Middle: Parsons scalloped the bone nut, something he says he picked up years ago while buidling flamenco guitars. Right: The finished Strolling with Bones. | ||

Some of your current work—like the Diablo—uses unusual materials such as bones, skulls, and other organic materials. What led you to incorporate those into your instruments?

That started all the way back with Boaz. We were staying up all night, thinking about what materials we could use for frets. The steel or nickel fret makes sense from a manufacturer standpoint, because you can hammer them in. But you would never use that material for a nut or a saddle. So we were coming up with these weird materials, like beryllium, bone, and this plastic called Delrin. It's really all about enjoying your art and enjoying life and resisting. I'm very stubborn—I'm trying to resist becoming a factory. I get enjoyment out of becoming a guitar maker, being original, and using different materials.

It's quite common to use bone for nuts, but what is the benefit of using bone and even cow skulls more extensively throughout the instrument?

Bone is just such a perfect material. I use the skull for interior bracing, and because of its honeycomb construction it's very lightweight and super, super strong. We've got these dead skulls sitting in the desert just being wasted, and I'm going to chop them up and use them for braces. It just makes sense. Tonally, they're great. They look cool, and it's a great resource. I do a lot of other things, as far as being green—I recycle materials you would never think of instead of buying new stuff or chopping down trees. Ultimately, I use these items because nothing competes with nature.

Sourcing quality wood can be tough for any luthier, but how does one go about procuring cow skulls?

You can discover this stuff by accident. In New Mexico and Mexico, they're lying all over the place so people just pick them up and sell them on the Internet. People hang them over their fireplace as a decorative thing. But they're out there, just lying around. They have to be bleached, dried, and hardened, and all the gunk inside needs to have gone away, but the outside of a cow skull is just so, so tough.

|  |

| |

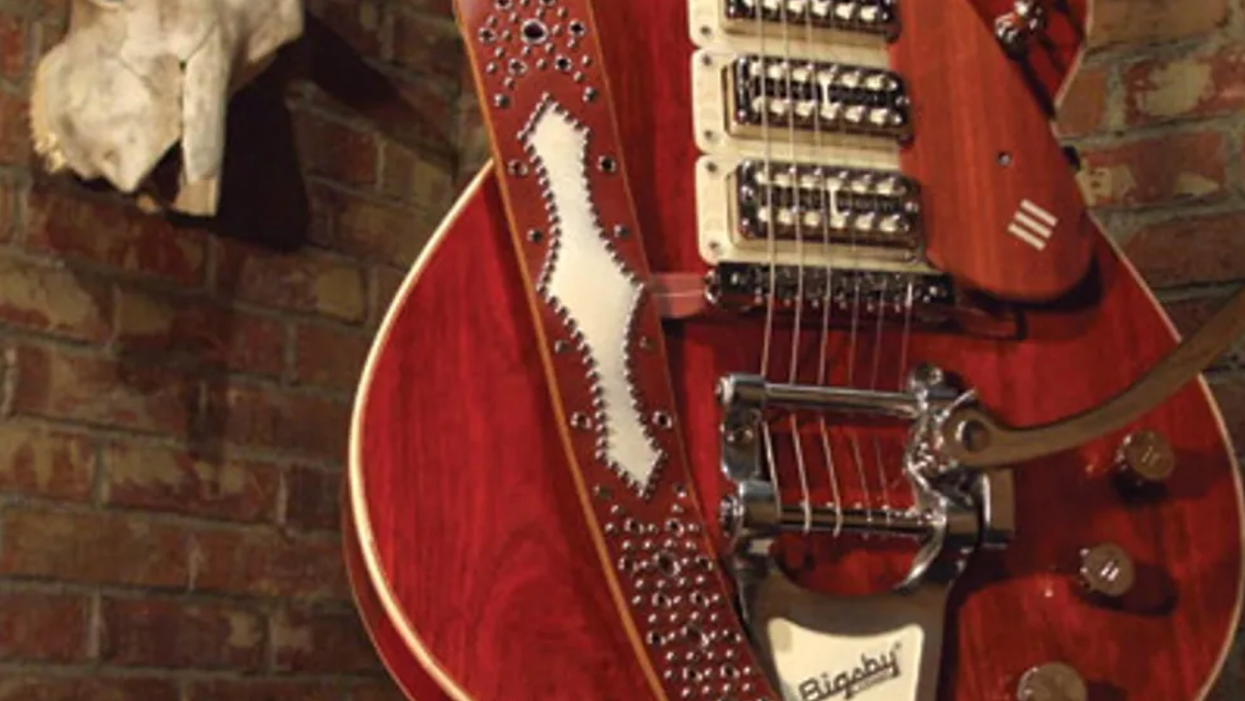

| Upper Left - Jack White's Gretsch-inspired Parsons Red Vampire features cow-skull bracing inside its semi-hollow African bloodwood body. Upper Right - The hollowed-out, three-piece neck is of African bloodwood and holly (“Bloodwood is just like ebony—very heavy and dense"), and the African bloodwood fretboard features cow-skull binding and thumbnail inlays. Lower Left - The back has four compartments—one for the onboard MXR Micro Amp pedal and three to facilitate fast repairs on the road. “Jack breaks things," Parsons explains. Lower Right - The finished Red Vampire is stocked with a an unusual bridge (“I bought a bunch of them years back from a smaller company, but I haven't been able to find any more") and TV Jones Classic Plus pickups with a unique switching system: The treble bout has three beefy on/off toggles “from a secret source," the bass bout has a killswitch (under the strap), and the knob complement consists of a master volume, a master tone, and a master gain for the Micro Amp. | |

While bone and other organic material might be lightweight, your Black Vampire model is made entirely of Gabon ebony. How much does that instrument weigh?

Well, before the fingerboard goes on, the whole neck is hollowed out. Again, kind of like honeycomb, so there's some structure there. And the body is semi-hollow, so the sides are bent like an acoustic. And the top and the back are one chunk of ebony that's shaped by hand. So it's a heavy guitar, but no heavier than a Les Paul.

The Black Vampire was built entirely of Gabon ebony for Microsoft co-founder Paul G. Allen. Its headstock is adorned with intricate scorpion carvings, and the back of the neck is inscribed with secret writings that are only visible under a black light. |

Why not just use multiple chunks of ebony?

The whole idea of one piece was just the uniqueness of it—y'know, the rarity. Here's a guitar made from the same piece of ebony just to keep it consistent. If I'm going to make a guitar out of solid ebony, I'm going to know that all my T's are crossed and my I's are dotted and do it right.

How would you describe the Black Vampire from a tonal perspective?

You would think the Vampire would be really cold and dark, but there's definitely an open, airy sound—kind of like an archtop. And I left the back of the neck unfinished, so it just feels great to play.

What are the pickups on the Vampire?

TV Jones Classic Plus models. Same thing on the Bruja model.

From your source materials to your model names—Strolling with Bones, Diablo, Bruja, and Vampire—there's a hint of the macabre to your work. Where does that come from?

It probably comes from my personality and the things I'm interested in. I think of myself as so normal, but then people come over to my house and ask, “Why is it painted like that? Why do you have dead cows hanging from the ceiling?" So I don't know. I'm just kind of one of those guys. I'm just a regular person that loves Halloween.

You joined the military in your 20s, which is a pretty unusual move for an artistic person of your background. What drove you to enlist?

I wanted an experience. I wanted adventure. It really was not my character to do something like that, but I just kind of panicked once I graduated from Cornish College of the Arts. It was like, “What the hell am I going to do with my life?" Music college was so liberal and so soft that I felt like I really needed to get beat up if I was going to do anything with my life. That discipline has really helped me to this day with my approach to guitar making and the way I run my business. I'm an anti-war guy, but in the military I learned you can achieve anything through hard work and never giving up. There's nothing wrong with getting a little bloody and bruised and just basically working your ass off.

|

| Left: Jack White hammering away at the Peach Thief guitar Parsons built for White's wife, singer/songwriter Karen Elson. Right: Randy Parsons poses in jest after White's round of chiseling on the Peach Thief. “I was trying to make fun of Jack for screwing things up." |

Jack White is one of your most well-known customers. How did that association begin?

It's just one of those phone calls you get. I had put myself in the right spot, I guess. Some person who knew me knew someone who knew Jack's drummer at the time. Jack had the idea for a new band called the Raconteurs and, instead of making everything red and white like he does with the White Stripes, he wanted his color of choice to be copper. So he was looking for someone to make a copper guitar. So, Jack's people called me with this idea for a guitar called the Triple Jet, and it was going to have three pickups and all this cool stuff. On the first guitar, we actually painted the top—it was a copper top with metallic paint. He played that for about six months, and then they started their tour and I didn't like it. One day, I said, “Why don't we just make the thing out of real copper?" I took about two months and made the actual Triple Jet #2 out of real copper, and that's the one he uses all the time now. It's his number-one guitar.

In the 2008 documentary It Might Get Loud, Jack White uses a guitar you built with a retractable microphone in the body. How did that design originate?

Jack could call some company and say, “Hey, there's no budget, sky's the limit, get your research team on it and make me this guitar." But with me, I'm just a one-man show. I had to figure it out, and it was a challenge. That guitar has a heavy microphone that he pulls out and screams into. He's very brutal onstage, so he lets it fly and then retract back up into the guitar. But of course I was like, “Oh yeah, I can totally do that." I bought a bunch of hair dryers and stuff with retractable cords, and I immediately discovered there was no way those parts were going to work—the bullet microphone weighs at least four pounds. I started talking to people in the industry that do big tools, but all their stuff was just huge and this guitar has a thin body. I finally ran into the Rain Man of vacuum cleaners: I walked into his shop and I just laid it out. I said, “This is the guitar, this is how much the microphone weighs." And he says, “The Hoover 2002 XL31." He went to the back of his shop and pulled out this wheel, and I swear to God this must be the only thing on the planet Earth that would fit into Jack's guitar and pull the microphone back inside. So I bought three of them and just kind of figured it out. That vacuum part is 10 years old, and we had some problems with it breaking down a few times on the road. I freaked out and went back to this guy to buy some more, and he had no idea what I was talking about. I'm like, “Man, come on! I came here six months ago and I showed you the guitar," and he just looked at me and said, “Nah, I don't know what you're talking about." So we're kind of screwed. We've got one wheel left, and that's it. But I think that's what Jack likes. He likes the fact that there is only one wheel and that if he's on the road somewhere and it breaks down, he's kind of screwed. He'll have to figure it out.

The finished Peach Thief features an armrest, a single TV Jones pickup, and petals from four sets of roses that were dried in books for three weeks. |

The guitars you've built for Jack have turned out so well that you're actually doing a signature Gretsch. What can you tell us about that instrument?

I made a guitar for Jack White's wife, Karen Elson. She wanted a guitar the color of a peach, and the idea was to just paint it that color. Of course, me and my big mouth, I said, “Why don't I find some peach-colored roses, dry the petals in books, and then glue them all over the guitar?" And that's what we did. The guitar is called the Peach Thief and looks like Jack's Triple Jet, but it has two pickups. I really like that idea of using flowers and organic petals. I came across these sunflowers, but instead of being orange and yellow, the leaves were dark, dark, blood red and black. So the new Gretsch guitar uses these pointy, sharp, sunflower-seed petals all over the front, with kind of a gray-black finish on the back and sides. It's very dark, very gothic, so it's actually called Sleeping Hollow. They pulled a Gretsch Anniversary Jr. off the assembly line and gave it to me to modify. I replaced the fingerboard, reshaped the guitar, changed the f-holes. It's a completely different guitar. They don't know quite what they're going to do with it yet, but they came to me because they wanted to identify with the rock-and-roll crowd versus the country cowboy crowd.

Back to your own brand, you've got a new model coming out in August.

It's the Diablo Antigua [August cover image], which is my new line and what I'm most excited about. I'm working with this incredible metal artist named Shawne Reeves, and this thing looks like it's 500 years old. It's got this cool copper etching all over the top, and the fingerboard is actually made from recycled newspaper and car tires. It's got aged copper block inlays. It has the cow skull construction and some other hidden stuff inside. One of the cool things about this guitar is that all the hardware goes through a two-step process. First, we copper-plate all the hardware before we do our acid treatment, because we turn everything black after it's been coppered. It just has this unique look that you can't buy anywhere. It also has a killswitch and a boost control—which are two things production guitars usually don't have.

What's the price point for the Diablo Antigua?

It ranges from $5000 to $7500. Most things at Parsons start there. What I'm trying to do is avoid doing production guitars. I'd rather offer my clients something that has value because it's handmade by me, so we do a small run every year of no more than 50 guitars.

A $5000 guitar is not entry level, but it's not outrageous either. A customer could easily drop that on a high-end axe off an assembly line. How do you create handmade quality while still keeping prices at least somewhat reasonable?

It's tough, because ultimately I want people to play them and be able to buy them. Five [grand] is kind of the area where, if I can get that much, I can continue doing what I do. I don't want to get greedy and just sell to collectors or rich people. But at the same time, I recognize that $5000 is a lot of money for a guitar. What I'm trying to say to someone is that you can spend $5000 on a Les Paul and it's going to hold its value and you're going to get a quality instrument. But you can also buy a guitar from me—that's actually made by me—and it may be worth a lot more in the future. This is the birth of a new company.

The Parsons Triple Jet that Jack White plays with the Raconteurs features a top made of copper. |

How are the repair locations in the area Guitar Centers set up?

The whole point is to get the name out there and brand it. So when you go there, you'll see the Parsons logo, and the shops are built by me and they're kind of dark and spooky. The Parsons vibe is there—it's not just a bench in the corner, that's for sure.

While female luthiers are not totally unheard of, it is somewhat unusual that you employ five women in your shop. What does this team bring to Parsons Guitars?

I couldn't be in a confined space for very long with another guy. I have this drill-sergeant mentality when it comes to training and dealing with people who work for me. If they're pretty girls, I back off a little bit. I don't think any guy could actually handle working for me, screaming and yelling all day long. The first to join my team about eight years ago was Dagna Barrera. She was an inlay artist and really knew her craft and was making acoustic guitars that made me say, “Wow!" I really enjoyed working with her and I thought, “I'm going to wait for more Dagnas to come through my door." Every couple of years, someone would show up looking for a job or training and, as long as they had a legitimate interest, I'd take them under my wing. So far, no one has left. They're like daughters. We're a big family. Now, if you're a female in a band in the Seattle area, you try to get a job here. Every cool chick that comes into town asks about doing an apprenticeship. I ask, “Do you know anything about building guitars or working on guitars?" And they're like, “No." But potential employees have to really want to do it. I'm looking for people that genuinely want to be a part of what I'm doing, that believe in it, and that see themselves as creating a career here and being here long term.

You've also built instruments for Jimmy Page. How did that occur?

In the movie, Jack is kind of talking about me and Jimmy listens. So I drunk-emailed Jack and said, “Call Jimmy for me, I've got this guitar I want to build him." Jack mentioned the movie premiere in Los Angeles and invited me to come down, meet Jimmy, and give him the guitar—which was a month and a half away. So I actually built Strolling with Bones in a month and a half. It was insane. I don't think I slept the whole time. The cool thing about that guitar is that it's based on the Kasha bracing system, which is a really cool way of making acoustic guitars. It's a cool guitar and it sounds pretty good, but I wasn't really happy with it.

How does one design a guitar for Jimmy Page? Does he ring you on the phone? Send email? Transmit telepathic missives?

Why are you calling the instrument the White Mare?

It's a line from the Zeppelin song “Going to California"—“Ride a white mare in the footsteps of dawn."

You're clearly interested in the esoteric—and you've said you're obsessed with the number 333, even going as far as assigning serial instruments in conjunction with it. How have these threads of the arcane and a strong sense of purpose guided your life and work to this point?

The number 333 is just a number that keeps appearing in my life when things are going good or something is about to go well. It's just everywhere—to the point where it's ridiculous. I went to someone professionally and said, “What the hell does this mean? Am I losing my mind?" And they said that it just means I'm on the right path. For some reason I'm just more attuned to it, and it definitely guides the direction of my instruments and the way I conduct my business. I'll never forget pulling up to the Beverly Wilshire hotel in the back of a cab when I was getting ready to go to Jimmy's hotel room and give him the guitar. That was definitely a very powerful, surreal moment when I sat back and reflected. I was very conscious of where I was and where this whole journey has taken me. I looked at the car in front of us and the license plate began with “333." Some people just aren't very conscious of things like that— even though they may be all around them.

What do you see in the next five years for Parsons Guitars?

To continue doing what we're doing and improve and build slowly. I've had opportunities in the past where people have shown up with money and they've said “Hey, we're going to do this and that and have your guitar manufactured over here." I've always resisted that—I've been very stubborn with my vision of creating a really unique, small guitar company that produces some real sick stuff. I'm very passionate about what I do or I wouldn't have been fighting for the last 15 years. Sure, I've always been in tune and aware of life's “spooky stuff," but I also believe in the science of business, in the science of hard work. Hard work is the key. You have to believe. I go through these periods where I'm so deep in my work that I start questioning—I feel like I'm treading water. But always, at the end, hard work prevails and something good comes of it.