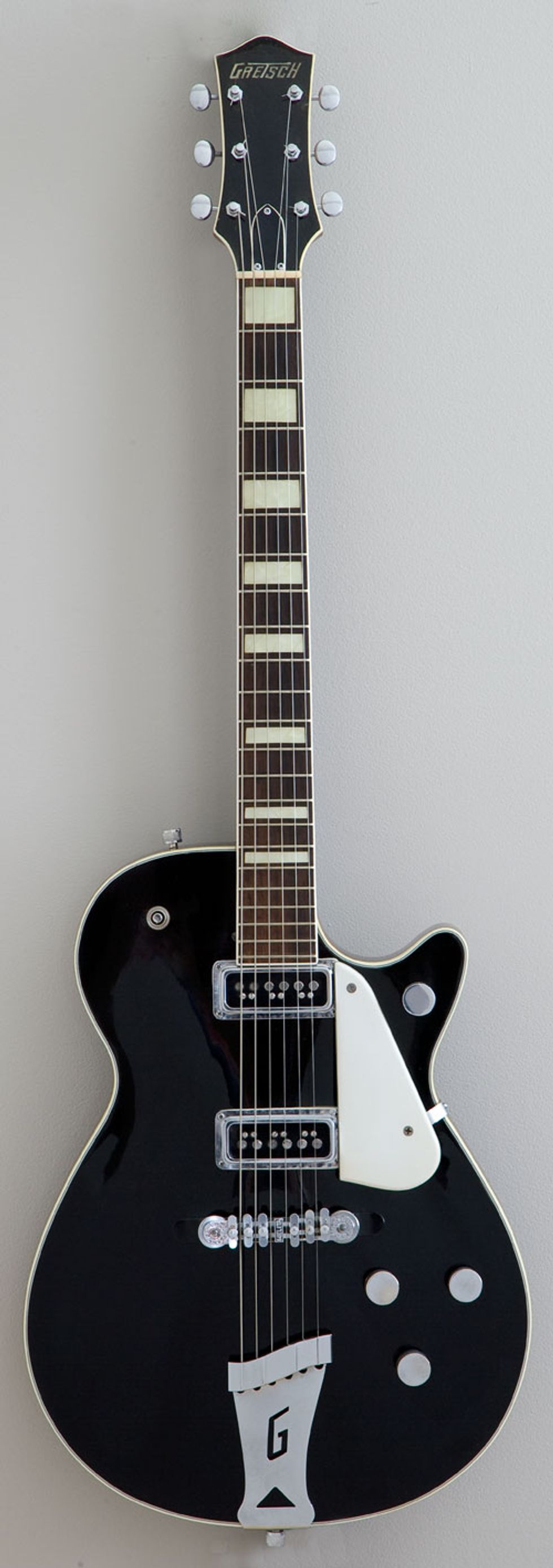

'61 Chet Atkins Country Gentleman model 6122

The Country Gentleman was the 17" wide body representative within the Chet Atkins signature series of electric guitars. Upon its debut in 1958 its sealed-top and faux f-holes foreshadowed the emergence of the Electrotone body design by several years. (Photo courtesy of Ron O'Keefe)