EarthQuaker HQ: (L to R) Gavin Smith, Ben Veehorn (circuit builder), Mike Stangelo (PCB population, wires, assembly), Steve Clements (circuit builder),

Jamie Stillman (founder/pedal designer), Julie Robbins (business manager), Elsa (support), Justin Seeker (senior circuit builder) Jeff France (production

manager), Brad Thorla (assembly). Photo by Stephanie Falk

“Affordable” is not a word often associated with boutique effect pedals. Nor is Akron, Ohio, normally associated with bands that fill Madison Square Garden. But while Akron’s Jamie Stillman was road managing just such a band—the Black Keys—he was simultaneously starting a line of great-sounding, handwired boutique pedals that would retail for little more than those of the mass-produced variety.

Despite boasting some deliciously cryptic names (Grand Orbiter, anyone?), Stillman’s effects often tend toward the meat-andpotatoes variety—boost/EQ, delay/reverb, fuzz, modulation, octave, and overdrive. But Stillman certainly has his own take on these stalwarts, often pushing the limits of their parameters on both ends.

Inspired by Electro-Harmonix founder Mike Matthews’ screw-the-noise-if-it-sounds-great MO, Stillman has likewise proven his mettle as both a designer and manufacturer: His EarthQuaker Devices stompboxes are as appealing to junkies on pedal forums as they are to those more worried about how their purchase will affect their pocketbooks. His is a classic entrepreneurial success story, with worthwhile lessons about carefully monitoring growth while staying true to your vision.

How did you get started

building pedals?

Around 2004, I had a DOD

Overdrive/Preamp 250 that I

loved. When the volume pot

broke, I decided I would just

replace it. I opened it up and

discovered there was nothing

much in it. I found the schematic

online and, for some

reason, it just made total sense

to me—so I decided to build

a new one. During my search

for the schematic, I found

websites like geofx.com and

generalguitargadgets.com and

got obsessed. I would stay up for

days reading about electronics—

I was constantly going to forums

to learn as much as possible.

Did you have any technical

background?

None, but I am able to understand

schematics like any

electrical engineer. Put me in

front of a microwave oven, and

I doubt I could rebuild it. But

put me in front of an effect,

and I can work on it. I can

also work on some amps and

guitars. I have been a tinkerer

my entire life. My folks have

photos of me taking apart an

abandoned car in the backyard

when I was in kindergarten. I

was always dismantling things

around my grandparents’ house.

What’s your musical

background?

I have been a musician forever.

I started on drums when I

was 5 or 6, and I started playing

guitar when I was 10 or

11—about 20 years ago. Until

about two years ago, I had

spent pretty much my entire life

touring in indie-rock bands—

from age 17 until 33. I played

drums in Harriet the Spy, and

guitar in Party of Helicopters.

More recently, I was in a band

called Teeth of the Hydra, and a

band called Drummer with Pat

Carney from the Black Keys. I

am currently in a band called

Relaxer. I also worked as a freelance

graphic designer and as

tour manager for the Black Keys

from 2004 to 2010—but any

spare second was spent learning

about electronics as they relate

to musical instruments.

Were you working on Dan

Auerbach’s equipment when

you were with the Black Keys?

I was not a true guitar tech—I

didn’t string guitars or anything

like that—but I helped

set up the equipment and

handled emergencies. I also built

tons of pedals for Dan. The

EarthQuaker Hoof Fuzz is based

on his green Russian Big Muff.

What was your next project

after the DOD clone?

I then started with the standards.

I built a Fuzz Face clone,

but I had to build that one 50

times to get it to work right

[laughs]—[it was, like] “The

first one was so easy, why is this

one so hard?” That taught me a

lot about transistor biasing and

how something so simple can

be such a pain in the ass.

Fuzz pedals are notoriously

difficult to get right—even

for experienced builders.

From the sound of the Dream

Crusher, it seems like you

eventually nailed it.

When you get them right,

they are awesome. The Dream

Crusher was my version of the

Fuzz Face. I try to get as much

range as possible out of the

fuzz and dirt pedals we make,

and while I’m in there I end up

cleaning them up. They are not

as gritty as a lot of other distortion

pedals, and I like that.

After that, I started building all kinds of things. I took pieces from one circuit and attached them to another—all the weird, mad-scientist things everyone who gets into this kind of stuff does. I spent about a year messing with different circuits, and out of those came the three pedals I used to start EarthQuaker Devices. One was the Spectre Overdrive, which was basically a couple of JFET [junction gate field-effect transistor] boosters driving each other … it didn’t work out so well.

In terms of sound or sales?

It sounded pretty good, but at

the time I really didn’t know

what I was doing. We built four

of them and they all went to

friends, but the JFETs ended

up frying each other—I wasn’t

treating them properly. Looking

back, I see every stupid mistake I

made. The second pedal, the discontinued

Tusk Fuzz, ended up

being part of our line. It wasn’t

really based on any other pedal.

The third was the Hoof Fuzz,

and that really set it all off in

2005. I launched the company

on breaks from Black Keys tours.

I basically put a bunch of pedals

up on eBay and sold mostly

the Hoofs. It got around on the

forums that the Hoof sounded

good, and then people found out

I was working with the Black

Keys and that didn’t hurt.

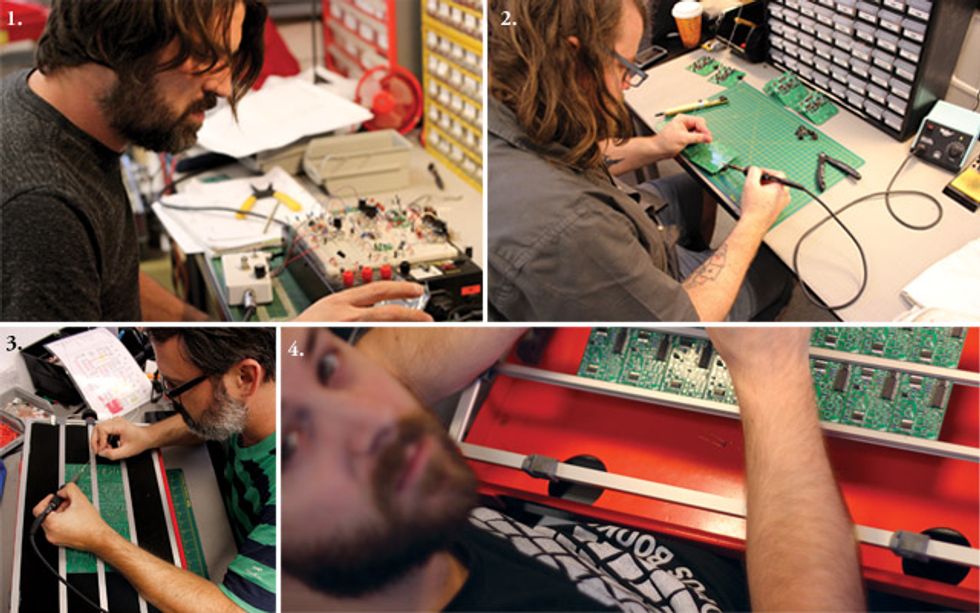

1. EarthQuaker Devices Founder Jamie Stillman works on a pedal bread board. Stillman does all of the pedal designing

and screenprinting for his stompboxes. (Photo by Stephanie Falk) 2. Ben Veehorn works on early stages

of pedal building in the circuitboard workstation. (Photo by Jeff France) 3. Senior Circuit Builder Justin Seeker

working on Earthquaker Devices circuitboards. (Photo by Jeff France) 4. Brad Thorla works with circuitboards and

pedal assembly. (Photo by Jeff France)

When you started the company,

what did you feel you

could offer players that was

missing in pedals already on

the market?

When I started building, I had

no idea there was a world of

people online talking about

boutique pedals. I had always

used pedals but was never

happy with them. I heard

sounds made by other bands

and didn’t know how to get

them: I didn’t know that there

was a difference between the

sound of a Marshall JCM900

and a Marshall Super Lead,

or a Boss Overdrive versus a

Big Muff. I was unhappy that

I wasn’t getting the sound on

Led Zeppelin records, without

realizing I wasn’t using anything

close to the same gear. Once I

started building pedals, I realized

these are those sounds!

As I started experimenting with effects, I began adding things that I wanted, like more low end or more clarity, while still having the pedal sound like an amp on the verge of blowing up. Modern effects were clean, pristine, noise-free—sterile. My goal was to make things that sounded old and kind of [expletive] up. Noise was part of those old pedals, like Echoplexes and old fuzz pedals—they didn’t work right, and that’s what sounds so good. Over time, I realized I was trying to mix old and new to come up with the sound that I had in my head. It turned out other people were into that sound, too. I read the Analog Man book interview with Mike Matthews of Electro- Harmonix, and a lot of his philosophies fall right in line with mine. If it does its job but there is some noise—[expletive] it.

You used to work as a graphic

designer—did you design the

EarthQuaker logo?

The octopus skull? No, I wish

I did. I redrew it a bit. The

octopus skull was a piece of clip

art that I cut out of this ’90s

punk-rock magazine called Crap

Hound, thinking I would use it

some day. When I started making

EarthQuaker Devices, I put

it on there and it became recognizable.

Still, I wish I had come

up with something of my own.

I ran across a guy who had a tattoo

of it—but not because of us.

He came across it on his own.

What’s your shop like?

I used to work alone out of

my basement, but by March of

this year we had seven people

working in 300 square feet. I

am an organization freak, so we

had things going up the walls

and stored on the ceiling. We

had used every square inch of

my basement, and it was time

to move. Now we have a shop

downtown with 2,000 square

feet that’s five minutes from

my house. We are in a couple

of rooms in a warehouse—with

windows [laughs]. It is a bombproof

fortress, most of it owned

by an Akron company that

builds bionic limbs. We have

run out of room there already.

Compared to other handwired

boutique pedals, your prices

are pretty affordable—almost

in line with mass-produced

effects. How do you do it?

Volume—we sell a lot of pedals,

mostly through stores and

distributors. At any given point,

we sell from one to five percent

direct. The pricing has always

worked out—from the time I

was doing it myself up until

now, with nine people and a

ton of expenses. The volume

kept increasing, and we’ve done

everything at the right time to

maintain that pricing. That is

not to say we don’t lose money

on some pedals. Some are not

making a profit, but I love

them so much I won’t get rid

of them.

LEFT: Steve Clements tends to the fi ner details, in the saudering of PCB population into pedals. Photo by Jeff France. CENTER: Pedals in the wiring stage at EarthQuaker headquarters. Photo by Jeff France. RIGHT: Mike Stangelo drills stomp switch holes into EarthQuaker Device pedals.

Photo by Jeff France.

When we started, the low prices turned some of the boutique buyers off because they assumed low price meant crap workmanship. But it is important to me to keep the effects affordable and keep making them by hand. Otherwise, what is unique about them? I think some boutique pedal buyers search out the most expensive pedals they can find, whereas we have crossed over to the general purchaser who walks into your average music store in the middle of Minnesota and says, “I want an overdrive pedal that does such and such.” The salesman shows them one of ours, and they go, “Oh, cool.” They might have come in looking for a Boss overdrive and they end up with one of our pedals. Then again, some of those people think our prices are a little high.

Do you take custom orders?

We used to, but we just can’t

keep up with it—I’m the only

one who can do custom stuff.

Most of the people who work

here do it like paint by numbers:

They get a build sheet

and they only know how to

build our pedals. If someone

wanted a purple Organizer [an

EarthQuaker pedal that produces

organ-like effects] with a

boost function, I would be the

only one who could do that—

and I don’t have the time.

We have hired more and more people, so actually building pedals has been out of my hands for a year, if not longer. My daily routine involves answering a ton of emails and fielding questions from everyone in the shop. My final hands-on thing with the pedals is hand-screening them and doing all the repairs. Sometimes we do custom colors for people because they happened to write us just when I was about to order enclosures, so I can throw in a one-off color. But in terms of fully custom pedals, I just don’t have the time— which sucks for me, because I like doing stuff like that. Occasionally, I will do a limited run of fuzz pedals because I like doing them.

Are you working on any new

pedal designs right now?

I haven’t had time lately to

design anything new, but I had

a lot of free time last year so I

have a backlog of ideas and prototypes

for new pedals.

Why EarthQuaker “Devices,”

rather than “Effects” or

“Pedals”?

It is my obsession with old

things—it sounds like an old

Japanese pedal company. It’s the

same reason I use “machine”

on the end of some of the

pedal names. I always thought

the old Foxx Tone Machine

name was really cool, or the

Hornby-Skewes Zonk Machine,

which is my favorite name for a

pedal—ever.

What kind of pedal was that?

I believe it was a treble booster

into a Fuzz Face. I’ve never seen

one, though.

Some EarthQuaker nomenclature

can be a little vague.

For example, is there any bit

reduction going on in the Bit

Commander synth pedal?

No—that confused everyone

at first. I was thinking in terms

of 8-bit sound as opposed to

a bit crusher. Maybe I should

have saved the name Bit

Commander for a bit crusher

pedal! [Laughs.]

Lastly, Production Manager Jeff France places knobs on the various pedals. Photo by Stephanie Falk

Is the Attack knob on the

Ghost Echo a predelay?

Yes. That is another one of

those confusing things that

makes total sense to me, but

when we first put it out people

were like, “What is this?” I like

to hover in the space somewhere

between reality and being totally

cryptic. About 50 percent of our

pedals don’t have instructions

for that very reason. Just plug it

in and mess around with it and

you will figure it out.

Was the White Light Overdrive

a reference to Lou Reed’s

“White Light, White Heat”?

No, I wish I were cool enough

to say it was—not that I was

unfamiliar with that song. I

seem to go through phases

when naming pedals. I was

coming off an animal phase and

moving into a short-lived color

phase with that pedal.

Why would you call an amazingsounding

fuzz Dream Crusher?

My wife named that.

Because you spent time

designing it instead of taking

her to dinner?

Yeah, right. I think I had the

graphic before we had the

name. It is based on the skull

inside the dream catcher.

It seems a little pessimistic to

call your delays—the Disaster

Transport and Disaster

Transport Jr.—“disasters”?

Dispatch Master [reverb/delay]

and Disaster Transport are

both Ohio references. Disaster

Transport is the name of a roller

coaster here at Cedar Point

[amusement park in Sandusky].

It was called Dispatch Master

Transport, but after an explosion

knocked off some of the

letters it read “Dis … aster

Transport.” Coincidentally, that

ride just shut down.

Tell us about the new

Talons pedal.

It is an overdrive that goes from

totally clean to full-on distortion,

with a fully active boost

EQ and a presence knob to

tame that last bit of high end. It

really covers a lot of ground—it

does a lot more than most

overdrive pedals I’ve played. I’m

really happy with it, and it takes

a lot for me to be happy with an

overdrive. I went through eight

completely different circuits.

Ironically, the end result was the

easiest circuit to work with.

How much of any given

design is based on customer

feedback?

Not a lot. You can’t please

everybody. I will sometimes

listen to our production manager,

Jeff France. He will come

up with ideas for additions

and subtractions, and he will

bluntly tell me if an idea sucks.

Ninety-five percent of the time

I go with my ideas, and five

percent will be his suggestions.

We get emails with suggestions,

but everyone who works here—

especially my wife—will tell you

I am very set in my ways and

usually use only my own ideas

[laughs].