Though there are many, many factors that contribute to the sound of an individual guitar besides the wood, the woods used in a guitar are probably the most discussed component of the instrument, and they are probably the most misunderstood. Some woods are better suited to guitar making than others and there are two main reasons for this: function and tradition.

The physics of the guitar are rather delicate. The strings on a steel-string guitar exert a tremendous amount of tension on the soundboard, which the luthier hopes to have at an ideal thickness to produce the best tone. It’s a balancing act between structural integrity and the resonance of the soundboard. If the board is too thin, it will warp; if it is too thick, it will sound dead or “thuddy.” Ideally, the soundboard will not warp against the tension of the strings and will also vibrate freely when the strings are plucked, thus moving the surrounding air and creating a pleasing tone.

The physics of the guitar are rather delicate. The strings on a steel-string guitar exert a tremendous amount of tension on the soundboard, which the luthier hopes to have at an ideal thickness to produce the best tone. It’s a balancing act between structural integrity and the resonance of the soundboard. If the board is too thin, it will warp; if it is too thick, it will sound dead or “thuddy.” Ideally, the soundboard will not warp against the tension of the strings and will also vibrate freely when the strings are plucked, thus moving the surrounding air and creating a pleasing tone. Tradition is a factor that is somewhat subservient to function. The Martin guitar company established the American steel-string guitar as the instrument we all know today. Their decision to use particular woods for these early, influential guitars was based on the factors outlined above. Rosewood was often used on many of their higherend guitars, simply because it functioned so well as a guitar wood. It is resonant, beautiful, stable and so on. Because Martin had such a formative role in the development of the instrument, rosewood became associated with high quality in general. The strength and longevity of these associations has engendered a tradition, though it could just as easily have been another type of wood.

When we say “alternative tonewood,” what we really mean is an alternative to the tradition of using certain woods in guitar making; keep in mind that rarely do these alternative woods veer very far from the traditional, because all these woods must be functional guitar woods. There are many reasons a luthier might choose to use an alternative tonewood – to carve a unique professional identity, to be environmentally responsible or to try and discover the next big thing.

In the following pages, we will highlight three of the most popular tonewoods: maple, rosewood, and mahogany, and the alternatives available for each.

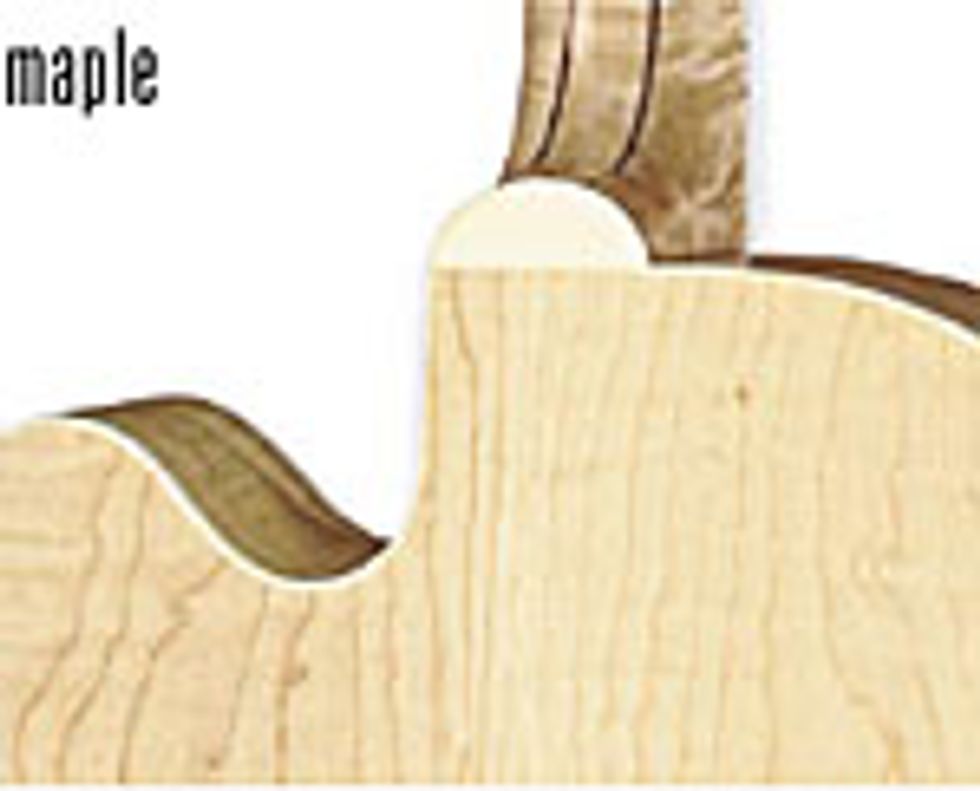

MAPLE

Maple is the only wood used for backs and sides in the violin family so it is well known to instrument makers, even though a modest percentage of guitars are made with it. The fact that it is a domestic wood augments its popularity and it is often used on electric guitars, most notably Gibson Les Paul tops.

Maple is the only wood used for backs and sides in the violin family so it is well known to instrument makers, even though a modest percentage of guitars are made with it. The fact that it is a domestic wood augments its popularity and it is often used on electric guitars, most notably Gibson Les Paul tops. Maple with figuring is preferred over plain maple, but the figure has no real bearing on the sound of the wood. The figure is, however, strikingly beautiful. Most common is curly maple, also known as flamed maple or tiger maple. A bit rarer is quilted maple, a wood with a billowy, bubbly appearance. Plain maple (Rock maple from the East Coast) is often used for electric guitar necks, but Bigleaf maple (from the Northwest) and European maple (from the former Yugoslavia) are the common choices for acoustic guitar back and sides.

Maple is well known for imparting a bright tone to an instrument, with excellent separation – a guitar with good separation allows each note of a chord to ring independently as opposed to sounding thick or clustered. It has long been a popular choice on the Gibson Jumbo series because the bright tone helps balance out the booming sounds of guitars with a large body.

Maple Alternatives

It is hard to find an alternative to maple, although tonally many have had similar results with Californian walnut. Walnut is primarily dark gray in color and can also exhibit dramatic figuring. Myrtlewood (also from the Pacific Northwest) has many maple-like qualities in tone and appearance, though generally the sets are more varied as far as color is concerned, with brown, gray and greenish vertical streaks being common.

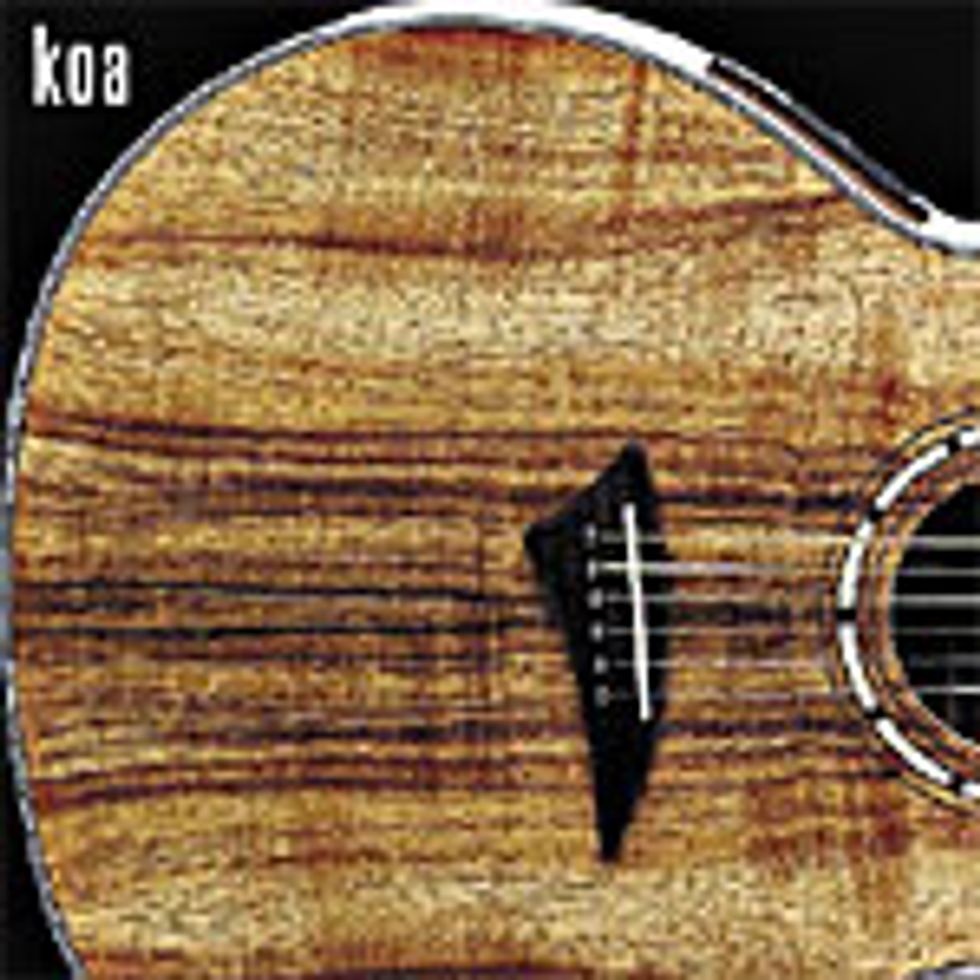

It is hard to find an alternative to maple, although tonally many have had similar results with Californian walnut. Walnut is primarily dark gray in color and can also exhibit dramatic figuring. Myrtlewood (also from the Pacific Northwest) has many maple-like qualities in tone and appearance, though generally the sets are more varied as far as color is concerned, with brown, gray and greenish vertical streaks being common. Another set of alternatives is koa from Hawaii and its Australian cousin, black acacia, otherwise known as Australian blackwood. These woods are among the most beautiful available, often found with a light, honey-brown color. They can combine vertical color bands with flamed figure, though flamed sets are becoming increasingly more difficult to come by. Though koa is technically not endangered, good old trees are few and far between on the islands and prices for the best sets are sometimes on par with Brazilian rosewood. Koa is sometimes compared tonally with mahogany.

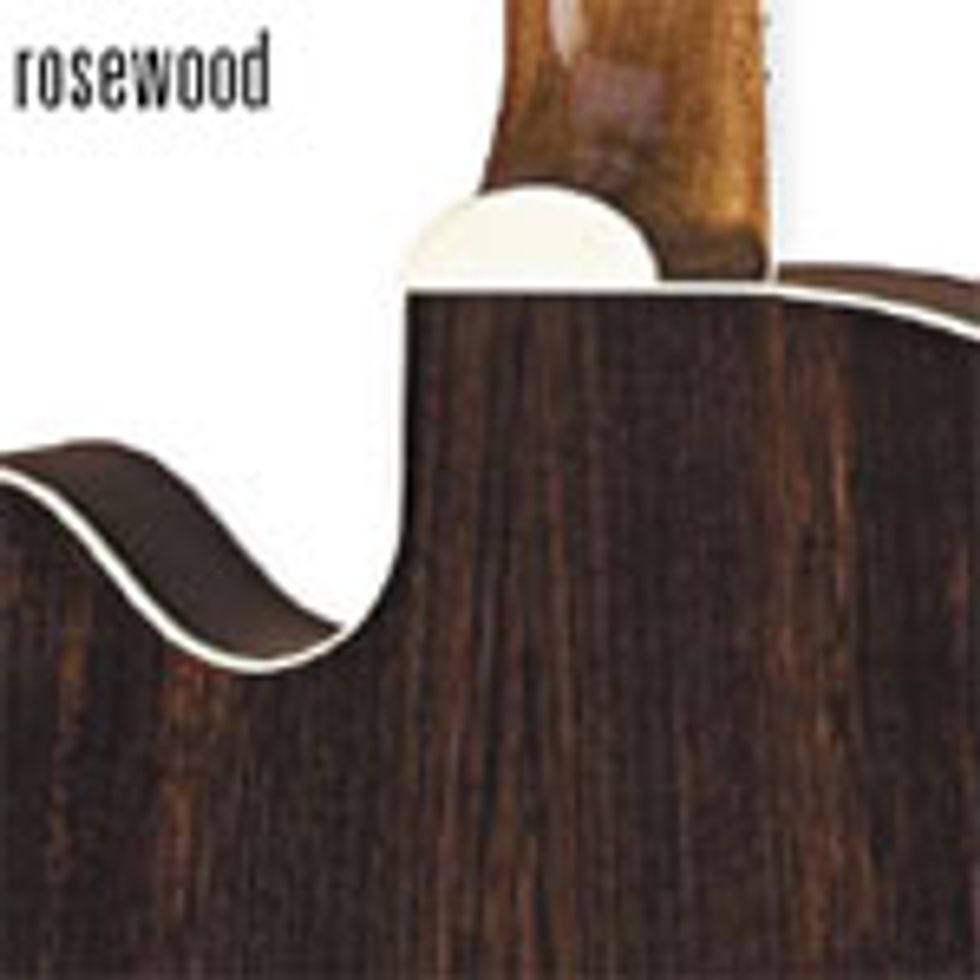

Rosewood

For many years the crème de la crème of tonewoods was Brazilian rosewood. Brazilian rosewood is sought after for its dark brown color that ranges from chocolate brown, to rust or a warm burnt orange. Finer examples feature fine black line figuring and spider webbing. Some say the tone is incomparable; great projection, with strong, balanced bass and highs are its trademarks. Though this wood is still in common usage, it has been protected against import and export by the CITES Treaty.

For many years the crème de la crème of tonewoods was Brazilian rosewood. Brazilian rosewood is sought after for its dark brown color that ranges from chocolate brown, to rust or a warm burnt orange. Finer examples feature fine black line figuring and spider webbing. Some say the tone is incomparable; great projection, with strong, balanced bass and highs are its trademarks. Though this wood is still in common usage, it has been protected against import and export by the CITES Treaty. The main alternative is Indian rosewood, which has become such a standard choice that it should now be considered a traditional tonewood itself. Basically brown, but with purple, gray and sometimes red highlights, it is known for straighter, more homogenous grain lines and a lack of ink-line figuring. Some say it is on par with Brazilian rosewood for tone, and it is far easier to procure and less expensive.

Rosewood Alternatives

There are a number of other woods that, because of their higher density, help create a rosewood-like sounding guitar, but do not come from the rosewood family. Visually, none of them would be mistaken for rosewood, but they are all quite attractive in their own right.

On the higher-end are Macassar ebony and ziricote. Macassar ebony is a black wood with dramatic blond streaking which creates a beautiful liquid or marbled appearance. Ziricote is grayish and features intense spider- web figuring and layered effects. Both woods are brittle and hard to work with, and both are expensive; however, their high density allows for great tonal balance and volume and the scarcity of well-figured sets adds value to the instruments.

On the higher-end are Macassar ebony and ziricote. Macassar ebony is a black wood with dramatic blond streaking which creates a beautiful liquid or marbled appearance. Ziricote is grayish and features intense spider- web figuring and layered effects. Both woods are brittle and hard to work with, and both are expensive; however, their high density allows for great tonal balance and volume and the scarcity of well-figured sets adds value to the instruments. The remaining rosewood alternatives are relatively inexpensive and easy to come by. From Africa there’s bubinga, which has a nice reddish-mauve brown color and often sports an interesting “bees-wing” figure that gives a nice three-dimensional shimmer to wood under finish. Also from Africa is padauk, a brilliant purple-red wood that oxidizes to dark brown over time. Finally, there is wenge, a very dark brown wood (verging on black) that some well-known builders, such as Mark Blanchard, have had good results with.

From South America there is grenadillo. This wood has a nice purple brown color reminiscent of Indian rosewood, except that it does not have the straight lines that Indian has. Grenadillo does have a subtle wavy figure, a bright responsive tap tone, and attractive sapwood centers are commonplace. It is popular in Brazil, but it is relatively new to American lutherie. It promises to become a favorite among steel-string builders.

From South America there is grenadillo. This wood has a nice purple brown color reminiscent of Indian rosewood, except that it does not have the straight lines that Indian has. Grenadillo does have a subtle wavy figure, a bright responsive tap tone, and attractive sapwood centers are commonplace. It is popular in Brazil, but it is relatively new to American lutherie. It promises to become a favorite among steel-string builders. Pau ferro (or morado) is well known as a fingerboard wood on electric guitars and basses and is coming into its own as a back and side wood. It is much like Indian rosewood with dark, straight, vertical lines except that gold, beige and brown substitute for the dark browns, grays and purples found in Indian rosewood.

Mahogany

Genuine Honduran mahogany has been an ideal choice for a variety of woodworking applications. Its cross-grained structure makes it unusually stable and easy to carve. It is a superb choice for woodcarvings, furniture making and pattern making. It is still the most popular choice by far for guitar necks, though Spanish cedar is widely used on classical guitars and maple is widely used on electric guitars.

Genuine Honduran mahogany was once in plentiful supply, but it is now nearing CITES treaty protection. The guitar-making world is struggling to find a suitable alternative for necks, but there is really no clear choice. Fortunately, the use of truss rods and graphite reinforcement in necks will allow the luthier to accept other mahoganies that are not quite as stable without any ill effects.

Genuine Honduran mahogany was once in plentiful supply, but it is now nearing CITES treaty protection. The guitar-making world is struggling to find a suitable alternative for necks, but there is really no clear choice. Fortunately, the use of truss rods and graphite reinforcement in necks will allow the luthier to accept other mahoganies that are not quite as stable without any ill effects. As a back and side wood, mahogany has sometimes been considered a “poor man’s choice,” but there is now a great appreciation for its unique tonal qualities. It seems that mahogany ages well and its true value may not reveal itself until a few years have passed. This is especially true when it is used as a top wood (Martin issues a mahogany-topped model from time to time). Mahogany’s trademark tone is a powerful midrange, with great punch and character.

Mahogany Alternatives

As far as stability is concerned, Honduran mahogany has no peers, but tonally there are some good alternatives. The best is Sepele mahogany, which features a very attractive ribbon figure that runs parallel to the grain. Khaya mahogany looks more like Honduran but is generally softer, so it is important to find dense logs when cutting for guitar material.

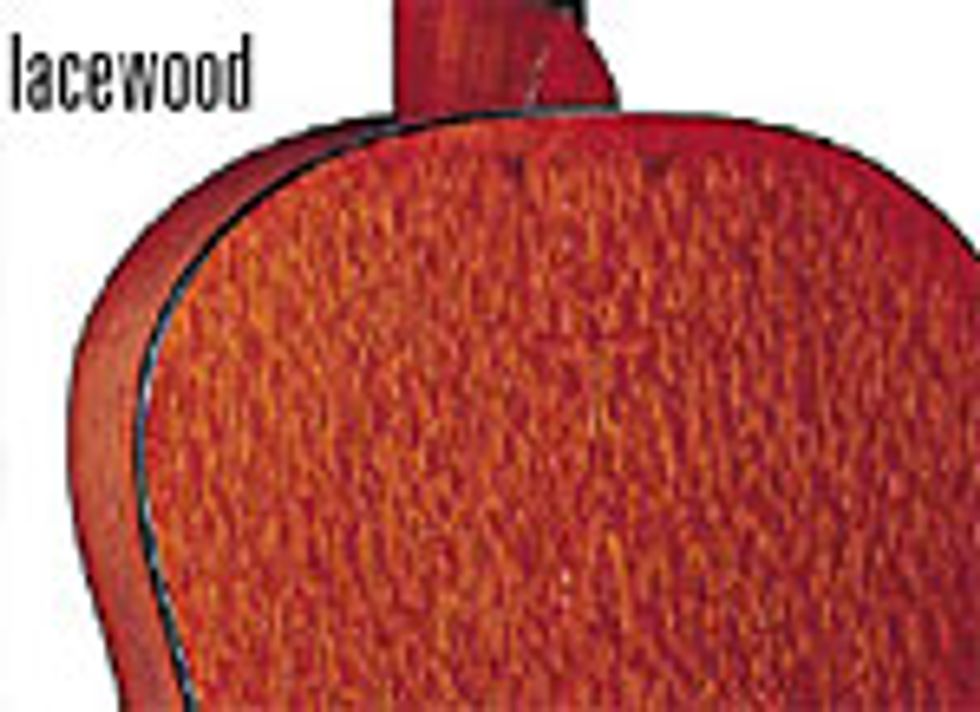

As far as stability is concerned, Honduran mahogany has no peers, but tonally there are some good alternatives. The best is Sepele mahogany, which features a very attractive ribbon figure that runs parallel to the grain. Khaya mahogany looks more like Honduran but is generally softer, so it is important to find dense logs when cutting for guitar material. Outside of the mahogany species, lacewood is the most exciting alternative. According to John Greven, a luthier who has built hundreds of guitars in his career and who has a great respect for vintage Martins, lacewood has the rare ability to impart the tone of a well-aged Martin mahogany guitar to a brand-new instrument. Fruit tree woods, most notably cherry and pear, sometimes draw comparisons to mahogany.

Where to Now?

Remember, each piece of wood is different and what each luthier does with the wood is unique. You can read about woods all you want, and you can tap and flex the individual pieces to test their tonality, but you will learn far more by playing the instruments themselves. Keep an open mind when searching for a new guitar, or when having one custom built. What a luthier might suggest may surprise you. Though tradition may direct you to select a guitar made out of this or that wood, your dream guitar may very well be born of a unique, and heretofore unheard of tree!

Elements of this article first appeared in Mel Bay Publications’ Guitar Sessions webzine at guitarsessions.com.

Chris Herrod is a Sales Manager for Luthiers Mercantile, Int’l