|  |

| Does the following scenario sound familiar? One day at band practice, thinking out loud, you say, “Man, my tone sucks!” Your drummer will ask what’s wrong with it, and you’ll fumble around for answers before uttering some generalized complaint like, “It’s just not… great. I want a really great tone.” |

He suggests you invest in a new amplifier, and after some more discussion, the seed is planted. You then try out the latest supercool boutique creation and declare, “This is it!” only to discover four months later that “this” is most certainly not “it.”

So there you are, back at square one with a hole in your wallet and a piece of gear that isn’t getting it done. What happened? What do you do next? What if this happens with the next piece of gear you try? Does all tone knowledge come from seemingly endless trial and error? Did iconic guitarists like Van Halen, Santana, Hendrix and Stevie Ray – players with instantly identifiabl tones – go through the same demoralizing searches? You just spent your vacation money on this amp and your wife will throw you out if you buy another one – there has got to be a secret to finding good tone that keeps your cash reserves liquid and your marriage solid.

The honest truth is it’s an equipment jungle out there and it’s easy to get lost. The good news is that the players mentioned above made it to the other side and so can you! Our eight-step tone checklist will help you identify the gear you need, before you open up the wallet, meaning a better chance of getting it right the first time. If you’re sick of spending money on gear that doesn’t get the job done, read on.

Head, Heart and Hands

Electric guitar tone begins before you ever pick up your instrument. It starts with your heart, is assembled in your head and lives in your hands; the gear you use is simply a conduit for the expression of these departments. You won’t find your tone in an amp, guitar, stompbox or rack unit unless you know what you’re looking for. The oftheard line, “I’ll know it when I hear it,” is nothing more than a cop out! Just because you can hear it in your head doesn’t mean you’ll ever figure out how to get it out of your hands.

| |

|

Ever heard this line before? “Smokin’ Johnny Hotlix played my rig and still sounded like Smokin’ Johnny Hotlix!” Why does this happen? Because Johnny Hotlix can answer all the questions above and apply those concepts to any rig. He is absolutely dialed into what he wants. And you’d best believe that he dug hard (just like you) to find it. Some players can do this naturally, like a gifted athlete; some folks stumble on it by accident. But the rest of us have to work at it.

But here’s the rub – I have no way of understanding what’s in your heart and how you create music with that source. That is what makes your art, your art. We’re certainly not here to discuss the esoterica of tone in your soul, and we’re not here to discuss the application of your God-given physiology, either. The point of this article is to help you get inside your head and make some decisions about your tone. Hopefully your heart and hands will follow suit. As there are so many little details that make up a signature tone, we’ll focus on the basics of what kinds of tones emanate from what kind of gear. We will use general classifications to help narrow down the wonderfully ridiculous number of gear choices out there. You will then be able to try a piece of gear and know what to listen for.

A quick note before we jump in: throughout this checklist you will see a lot of adjectives regarding tone. Almost every description has an opposing point of view. Please understand that our purpose here it to generally classify, not define.

Checklist Point #1: Clean Tones

The amplifier is where clean tones are delivered, and provides the foundation for the rest of your tone. Today’s amps deliver thousands of styles and colors of clean tones, so how does one narrow it down? Let’s start by identifying the four basic types of clean tones that the rest are derived from.

“Fender-style” Clean: In the 1950s, Leo Fender and his amp company pioneered this style of tone, created by the use of 6L6 power amp tubes and a Class A/B power configuration. Look for a sparkling, clear and open sounding color. The highs cut hard, the mids are transparent and crisp, and the lows are dry and clear.

| |

|

“Marshall-style” Clean: In the 1960s Jim Marshall used EL34 power tubes and a Class A/B power configuration to create a signature clean sound with a round, warm high-end, punchy midrange, and thick, level lows. Amps such as Marshall’s Plexi and JCM series, Dr. Z Amps and the Mesa Stiletto deliver this flavor. Artists such as rock godfather Jimi Hendrix, The Chili Peppers’ John Frusciante, and the Allman Brothers’ Duane Allman and Dickey Betts use (or used) this tone to define their styles.

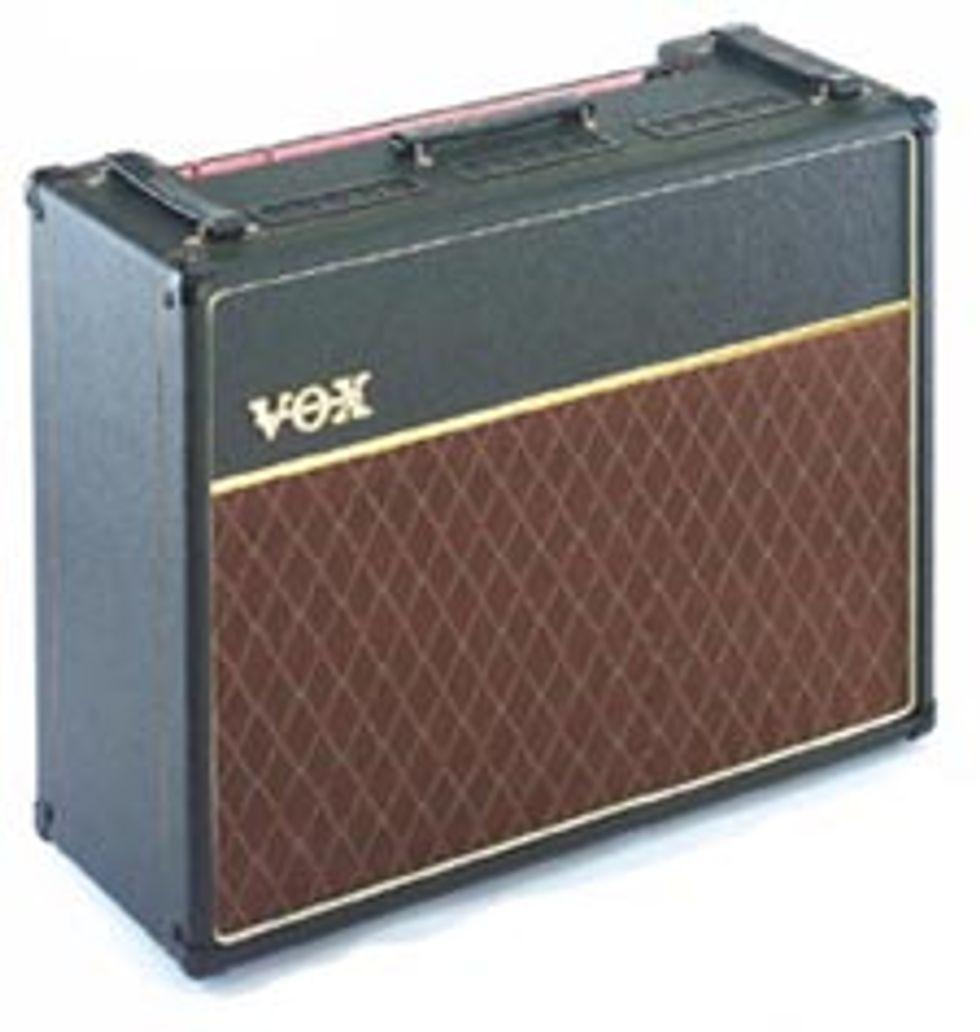

“Vox-style” Clean: The British Vox Company developed and popularized a clean tone unlike any other with some unique preamp tube choices, EL84 power amp tubes and a Class A power configuration. Characterized by scrunchy highs, a warm midrange, and soft, full lows, Vox amps do their own thing. Amps such as the Vox AC30, the Carr Hammerhead and the Orange Tiny Terror produce this spice. Brian May of Queen, The Edge from U2 and jazzbo extraordinaire John Scofield (a recent convert) can be seen using Voxes for their signature clean tones.

| |

|

But which one is right for you? Here is where those difficult questions start. How do you want your clean tone to feel? Cutting? Smooth? Raw? Fat? Think about the environment you’ll be playing in – what instruments will you be blending with (if any)? Are you using more than one clean tone? How much do you use your clean tone – is it as important, or less important than your distorted tone? Also take into consideration volume and headroom – where are you playing, and how much volume do you need to cover the space? Ask these questions and let them lead you to your own questions. Learn to describe in detail the clean tone you hear in your head. Once you can accomplish that, you’ll be on your way to finding your own sound.

But which one is right for you? Here is where those difficult questions start. How do you want your clean tone to feel? Cutting? Smooth? Raw? Fat? Think about the environment you’ll be playing in – what instruments will you be blending with (if any)? Are you using more than one clean tone? How much do you use your clean tone – is it as important, or less important than your distorted tone? Also take into consideration volume and headroom – where are you playing, and how much volume do you need to cover the space? Ask these questions and let them lead you to your own questions. Learn to describe in detail the clean tone you hear in your head. Once you can accomplish that, you’ll be on your way to finding your own sound. Checklist Point #2: Distortion/Overdrive Tones

Dirt, glorious dirt. The right kind equals bliss, while the wrong kind often equals barf. There are quite possibly, and without exaggeration, hundreds of thousands of distortion colors on the market and you can get your distortion in a variety of ways. Here are a few categories to help explain it all.

| |

|

There are tons of uses for these little jewels. You can use them to distort a clean amp signal, further distort a slightly distorted amp signal, boost the guitar’s signal, filter it for timbre purposes, distort an effected signal, send a distorted signal to an effect or any one of umpteen options. The Ibanez Tube Screamer and the Boss Blues Driver are popular overdrive boxes, while the Krank Krankshaft and the DigiTech Distortion Factor are popular with metal mavens. The Electro-Harmonix Big Muff and the Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face are popular with the psychedelic fuzz crowd.

Overdriven Amp: Take a good tube amp from the sixties and turn every knob all the way up. You’ll get a preamp and power stage pushed to their limits, thereby creating a mild distortion rich in singing overtones. This is the sound of early rock n’ roll and blues. Since the amp is doing all the distortion work, circuit designs and tube choices play a huge part in shaping the tone and flavor of the overdrive. From Hendrix and Clapton in the sixties, to Angus Young and Ritchie Blackmore in the seventies, to modern overdrivers such as Pearl Jam’s Gossard and McCready, there are a multitude of overdriven amp flavors to choose from. You’ll want to spend some time listening to your favorites to nail down a specific tone.

Cascading Gain Circuits: As the seventies rolled around, amp manufacturers realized that distortion was a good thing and began looking for ways to create more. Californian Randall Smith (of Mesa Boogie fame) began modifying Fender amps with a new preamp design that multiplied the number of gain stages. Thus began the era of the high-gain amplifier and the sound of modern rock. These amps create thick, rich distortion with chunk, drive and a girthy buzz with more distorted definition than pedals or previous amp circuits. Most major manufacturers now have high-gain amps in their line, with Mesa’s Dual Rectifier and Marshall’s TSL and JVM series being popular favorites. Some distort moderately and some rage like an underfed Doberman – James Hetfield, John Petrucci and Steve Vai are just a few of the more famous players falling into this category.

| |

|

Of course, not all solid-state amps are modeling amps. With tight, focused distortion colors, defined overtones and a rounder attack, many players prefer solid-state tone. Ty Tabor used these amps for his unique signature tone on King’s X’s first four discs, and “Dimebag” Darrell Abbott used them for the entire Pantera catalog. Megadeth’s Dave Mustaine is a recent modeling convert and has added them to his live rig. It should also be noted that as a category, these amps are generally less expensive than tube amps, which make them very attractive to the guitarist on a budget.

Which type of grit is right for you? This one is a little tough, because circuit design variations within each category mentioned above drastically affect the distortion flavors, but we can still ask some basic questions to get you thinking about your tone. How do you intend to play with your dirt? Is it the cornerstone of your sound, or is it just for solos? Do you have to worry about covering up other instruments, or making the mix muddy? Do you need one dirty tone, or several at different levels? You need to be able to describe each sound in detail, whether it’s sweet, singing, ballsy, freaky, chunky, nasally, grinding, thick or focused. Once you ascertain what your needs are in detail, you’ll be able to narrow down the vast amount of distortion options and find a sound that fits you.

Which type of grit is right for you? This one is a little tough, because circuit design variations within each category mentioned above drastically affect the distortion flavors, but we can still ask some basic questions to get you thinking about your tone. How do you intend to play with your dirt? Is it the cornerstone of your sound, or is it just for solos? Do you have to worry about covering up other instruments, or making the mix muddy? Do you need one dirty tone, or several at different levels? You need to be able to describe each sound in detail, whether it’s sweet, singing, ballsy, freaky, chunky, nasally, grinding, thick or focused. Once you ascertain what your needs are in detail, you’ll be able to narrow down the vast amount of distortion options and find a sound that fits you. Checklist Point # 3: Pickups

Electric guitars are a peculiar beast – while they often look relatively straightforward and utilitarian, every component of the instrument contributes to your tone. There are, however, four main things we can examine to help you zero in that sound: pickups, body type, woods and components. We’ll begin with the pickups, as they actually transmit the string vibration to your amp.

| |

|

Single coils: Having only one coil (a magnet wrapped in wire), these pickups remain one of the most versatile designs around. Developed in the fifties, Leo Fender’s single coil pickup – found in Fender Stratocasters and Telecasters – has become a standard for many players, producing a clean, clear, crisp, biting sound. These pickups generally have a medium to low output resistance and phasing characteristics that enable the pickups to cut through a mix.

Of course, there are plenty of other options here. Introduced by Gibson in the forties, the higher-output P-90 produces a fat midrange with lots of punch. Likewise, the eighties gave us Lace Sensors, which are classified as single coils, but use compression magnetics rather than the standard slug coil technology used in most pickup designs. This technology produces a slightly mellower tone, but virtually eliminates the pesky 60-cycle-hum associated with single coils.

| |

|

Piezo: These pickups were designed to amplify acoustic guitars but have been used on electric guitars to great effect. Essentially ceramic transducers – as opposed to magnets – they produce a resonant, somewhat quacky tone with lots of hollow (notched), ambient overtones. Godin’s Multiac is a very popular piezo-equipped axe. Players who don’t want to lug an acoustic to a gig often use piezo-fitted electrics. Jazzers and janglers alike often use a blended mix of single coil or humbucking pickups with a piezo tone.

Which pickup or pickup configuration is right for you? How do you want to use your pickups? Do you need one sound or several? Do you need lots of highs, or do you want your tone to be fat? Do you want it to cut, but not feel thin? Remember that creating a personal tone often means using things in a manner they were not intended. Jazzer Mike Stern uses a Yamaha custom Telecaster-style guitar with a single coil in the bridge – not the first choice for your average jazz cat. Some folks – Scott Henderson, for example – think that single coils work better in a trio because of their wide sonic throw, rather than their ability to cut through. Once again, if you ask the tough questions, you’ll get the answers you’re looking for.

Which pickup or pickup configuration is right for you? How do you want to use your pickups? Do you need one sound or several? Do you need lots of highs, or do you want your tone to be fat? Do you want it to cut, but not feel thin? Remember that creating a personal tone often means using things in a manner they were not intended. Jazzer Mike Stern uses a Yamaha custom Telecaster-style guitar with a single coil in the bridge – not the first choice for your average jazz cat. Some folks – Scott Henderson, for example – think that single coils work better in a trio because of their wide sonic throw, rather than their ability to cut through. Once again, if you ask the tough questions, you’ll get the answers you’re looking for. Checklist Point #4: Body Style

| |

|

Hollowbody: The first electric guitar was an arched top, acoustic f-hole guitar with a pickup attached to it, and not much has changed since. With a hollow, resonant sound and lots of woody overtones, these guitars react strongly to the kind of strings used. Being completely hollow, the entire guitar becomes a resonant chamber. Gibson’s ES-175 and Ibanez’s AF75 are popular hollowbody choices. Primarily used in jazz, the hollowbody is favored by everyone from jazz genius Pat Metheny to the ever-funky Eric Krasno from Soulive.

Solidbody: A solidbody electric is basically a solid piece of wood (or several pieces laminated together) with the strings, neck and pickups attached. It has no resonant chambers and creates a tight, directed, focused attack with narrow and specific overtones. It is the weapon of choice for most guitarists, from blues to rock to country and beyond.

Semi-hollowbody: Take a fat hollowbody and make it thin; then stick a solid wood center block inside the guitar, from the neck tenon to the tailpiece, leaving the “wings” hollow and the center solid. The result is some of the resonance and overtones of a hollowbody, with some of the focused attack of a solidbody. Semi-hollows have a quite pronounced midrange punch, with Gibson’s ES-335 remaining one of the most recognizable guitars in this category.

So what body style is right for you? Ask yourself how “open” do you want your guitar to be. How important are resonance and overtones to you? Some players want as tight a tone as possible. Consider how loud will you be playing, and in what kind of environments – semi-hollows and hollows often wrestle with feedback at higher levels, although a young Ted Nugent famously made this work for him. Some players fill their hollowbodied guitars with stuffing to control feedback while keeping the resonance. There’s also the practical – how much weight do you want hanging around your neck for prolonged periods of time?

So what body style is right for you? Ask yourself how “open” do you want your guitar to be. How important are resonance and overtones to you? Some players want as tight a tone as possible. Consider how loud will you be playing, and in what kind of environments – semi-hollows and hollows often wrestle with feedback at higher levels, although a young Ted Nugent famously made this work for him. Some players fill their hollowbodied guitars with stuffing to control feedback while keeping the resonance. There’s also the practical – how much weight do you want hanging around your neck for prolonged periods of time? Checklist Point #5: Woods

| |

|

Mahogany: Mahogany is one of the most common woods used in electric guitar construction, and for good reason. Mahogany is a rich sounding wood with a resonant structure that accentuates the midrange frequencies. It is a dense, open sounding wood that vibrates well, becoming more resonant with age. It also plays well with other woods (the Les Paul’s mahogany/ maple cap, as an example).

Maple: High-end frequencies abound wherever maple is used. Not often used as a body wood due to its weight, it provides a snappy and bright tone. It is often used as a neck wood to create more attack and brightness in cooperation with warmer body woods. Flamed, curly, birdseye, spalted, burled and other figured maples are quite striking visually, and are often used as body caps (tops) to provide both good looks and some extra “snap” in tone.

Swamp Ash: Swamp ash is a common, lightweight, “soft” wood used in many guitar bodies today. Some players swear by this wood’s upper-midrange overtone structure and sustain, making it popular with the shred crowd. Ash has an open, warm tone that smoothes out the attack a bit, while remaining very resonant.

Basswood: Basswood is a soft, light, wood that has no figuring and is used by guitar companies for solid finishes on less expensive models. However, basswood guitars have vibrant sustain and pronounced highs and mids. Some brave companies, like Parker, use basswood for their necks, due to its consistent tone and lack of dead spots.

Alder and Birch: Alder and birch come from the same tree family and share very similar tonal and resonant characteristics. These woods generally have a brighter tone and are not as dense as mahogany. They have plenty of warmth and sustain, and are lighter weight. Clapton’s famous “Blackie” Strat featured an alder body.

Ebony and Rosewood: These woods are primarily used in fretboard construction due their density and durability. Ebony provides a “stiff” feel and snappy attack; rosewood is less dense and offers a “softer” feel. Rosewood is used occasionally as a body wood, offering a tone similar to mahogany with more highs.

Other Exotic Woods: We live in a gigantic world with thousands of tree varieties. One could theoretically make a guitar out of just about any wood. Brian May made his famous Red Special out of his father’s fireplace mantle! The tonal properties of exotic woods vary greatly; if you are going to use an exotic tonewood, it is important to ask plenty of questions regarding the actual piece of wood you will be using. Make sure it fits your needs.

When contemplating tonewoods, do your homework. Are you thinking about building your own custom instrument, or are you buying off the rack? Do you want a darker or lighter sound? Which woods tonally compliment each other? For example, some Fender Strats have a maple neck, rosewood fingerboard and an alder body. What is the purpose for this combination? How would the sound change if you went with a basswood body? What about a maple neck and fingerboard?

When contemplating tonewoods, do your homework. Are you thinking about building your own custom instrument, or are you buying off the rack? Do you want a darker or lighter sound? Which woods tonally compliment each other? For example, some Fender Strats have a maple neck, rosewood fingerboard and an alder body. What is the purpose for this combination? How would the sound change if you went with a basswood body? What about a maple neck and fingerboard? Checklist Point #6: Components

It may seem like we’re really delving into minutiae here, but even your guitar’s components will have a big impact on your tone, as they either handle the actual signal path (after the pickups) or are part of the string’s vibration.

Tuning Machines: When it comes to tone, your tuning pegs are all about vibration transfer. Installed properly, good pegs will transfer string vibration into the headstock and neck – once the neck and body begin to vibrate together, you get sustain. A tuner’s mass has the ability to affect the sustain; likewise, companies that manufacture “locking pegs” claim to transfer the vibration of the string through the peg quicker and truer than standard pegs.

| |

|

Likewise, bridge saddles can greatly change your tone, as it’s the first place a string’s vibration gets transferred to the guitar’s body. Brass saddles are warm and tight sounding; standard steel is bright and ting-y; stainless steel offers an even brighter option; and coated and composite saddles generally offer mellower options.

Bridge and Tailpiece: Stop bar tailpieces stop the string after it “breaks” over the bridge with a bar bolted into the guitar, providing an immediate transfer of vibration at the bridge. The denser the metal used here, the better the transfer. Stringthru designs stop the string inside the guitar’s body, with individual string holes routed into the body behind the bridge. The idea here is to “attach” the string to the body, allowing the string complete resonant opportunity. Fender-based tremolo designs stop the string inside the bridge, transferring vibration from the string at the bridge fulcrum through the springs inside the routed body cavity. Locking tremolo systems lock the string down at the bridge and the nut to ensure stable tuning during whammy abuse. These designs were once known for killing tone, but a lot of sweat has gone into making new locking trem systems as resonant as any Fender-based system.

| |

|

If you’re planning on buying a stock guitar, your components may matter little; however, for anyone considering a custom built guitar, you will again want to ask these important questions. Do you love the sound of whammy abuse, or would you rather put in a stop tailpiece for more vibration transfer? Is tuning stability a concern for you? How important is sustain to your playing? Alternative nuts and saddles may cost more, but if you value sustain, it may make sense to spend the extra cash.

If you’re planning on buying a stock guitar, your components may matter little; however, for anyone considering a custom built guitar, you will again want to ask these important questions. Do you love the sound of whammy abuse, or would you rather put in a stop tailpiece for more vibration transfer? Is tuning stability a concern for you? How important is sustain to your playing? Alternative nuts and saddles may cost more, but if you value sustain, it may make sense to spend the extra cash. To sum up points 3-6, choosing a guitar is a matter of feel and tonal nuance – there are now tons of options available for tone hunters. Prior to buying a guitar, determining the kind of pickups, body style, woods and components you need will make your search more manageable. If the guitar does what you want, it’s because of the choices you make. Ask yourself exactly what you want from your guitar.

| |

|

What’s the cheapest way to improve your tone? Change your strings! The type of metal used in your strings, the size of the string and the way your string vibrates all define your tone.

Alloy Type: Nickel-steel is the most common string type, providing a balanced tone with tight highs, punchy mids and clear lows. If you’re looking for more highs and increased definition in your sound, go for stainless steel – Scott Henderson does. Pure nickel offers a slightly softer, yet alive alloy that Eric Johnson uses and many players swear by. Most alloys come in coated versions that, to some ears, mellow the output and attack ever so slightly.

Winding Type: The type of winding used on a string will also determine its sound. Roundwound strings are the most common and are found on 90 percent of all electric guitars for their clean, clear overtones and definition. Flatwound strings grind the rough edges off the string for a smoother feel, and produce a fatter, much less biting tone with less sustain and a smoother attack. Smack dab in the middle, tonally, are semi-flatwound, or “bright flat” strings. While roundwound strings are used in all kinds of music, flatwounds are primarily found in jazz.

String Gauge: The thickness (gauge) of a string will determine its dynamic headroom, tension and overtones. Simply put: the heavier the string, the higher the string tension. This gives you more headroom, allowing you to hit the string much harder without it “flattening out.” Thinner gauges (.008 and .009) work well for players who rely on smooth distortion and a light touch. Medium gauges (.010 and .011) provide more dynamics while still retaining good sustain and feel, while heavy gauges (.012 and .013) provide the most headroom, attack and focused overtones, but can make you fight your guitar with each solo. Detuned metal gods use heavy gauges to compensate for the decreased string tension detuning results in.

Which string type is right for you? Once again, determine your needs. Think about your playing style – do you use a heavy pick and aim to destroy your strings with every down stroke? Do you detune? What about the action of your guitar? Do you need sustain from your strings or lots of attack? Is string feel important to you? Feel and tension even vary from brand to brand. Working with various string types and brands will give you the quickest and cheapest way to help you find your tone.

Which string type is right for you? Once again, determine your needs. Think about your playing style – do you use a heavy pick and aim to destroy your strings with every down stroke? Do you detune? What about the action of your guitar? Do you need sustain from your strings or lots of attack? Is string feel important to you? Feel and tension even vary from brand to brand. Working with various string types and brands will give you the quickest and cheapest way to help you find your tone. Checklist Point #8: Plectrums

Picks are where things get crazy, in terms of the sheer number of options. Comfort is the criteria most players use when deciding on a pick, but picks are all about tone, too. Today’s plectrums are being manufactured out of a range of materials, all producing different sounds: celluloid, molded plastic, nylon, acetyl polymer, delrin, tortex, aluminum, nickel, silver, gold, copper, brass, cork, ceramics, graphite, rubber, stone, ivory, wood, felt, glass, and the list goes on. And that doesn’t even take into consideration different shapes, all of which will change your attack. Pick thickness also plays a role in both comfort and tone; picks are available in thicknesses anywhere from 0.18mm (the approximate thickness of a G string), all the way to 5.5mm (the approximate thickness of two quarters). In general, strummers seem to like thin picks and accurate speed pickers seem to like stuff around 1.0mm. There are even special effects picks! The Jellyfish uses rows of tiny metal dowels at a 45-degree angle – the company claims that it makes your guitar sound like a 12-string. Now that’s value! Experimenting with picks (or lack thereof) can be one of the most personal things about your tone. Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top used a quarter for his famous solos in “La Grange.” Top’s tonemeister even says that if you want a real “international” sound, use a Peso. After 30 years, Jeff Beck dropped the pick and decided to play with his fingers; likewise, many hybrid country pickers grow their nails out in lieu of a pick. The perfect pick may be closer than you think.

A Word or Two About Effects: You might have noticed that a checklist point regarding effects is conspicuously absent in this article. The reason? Effects do just what they are advertised to do: they affect your signal. Whether effects are a big or small part of what you are trying to do, it’s important to define your core tone(s) first. If the ideas for your core tone(s) aren’t solidified, effects orchestration becomes a hell-bound spiral of death. Why? Simply put, if you are tweaking effects and it sounds like crap, you have to ask yourself, “Is it the effect or the tone?” Get your tone together first and you’ll avoid this conundrum.

A Word or Two About Effects: You might have noticed that a checklist point regarding effects is conspicuously absent in this article. The reason? Effects do just what they are advertised to do: they affect your signal. Whether effects are a big or small part of what you are trying to do, it’s important to define your core tone(s) first. If the ideas for your core tone(s) aren’t solidified, effects orchestration becomes a hell-bound spiral of death. Why? Simply put, if you are tweaking effects and it sounds like crap, you have to ask yourself, “Is it the effect or the tone?” Get your tone together first and you’ll avoid this conundrum. So What’s Left?

Simply go down the checklist and ask yourself the questions at the end of each point. They should serve as springboards for your own questions. Once you’re able to answer all of your own questions and can truly define your tone (you may want to try doing it on paper), you’ll be able to start intelligently looking for the gear you need, without wasting precious time or money. And that’s when the fun part begins! Start tying different combinations of gear at every music store you can think of. Hang out with your friends and swap gear for a day or two. Try every combination of equipment that makes sense for your circumstances, and test-drive that gear in your playing situation, even gigs if you can. Ask questions, use descriptions and let good salespeople help you. Use reviews, but make your own decisions. Read everything you can find on the subject of tone. And make sure to buy from the store you tested the gear at! If you follow these steps, you’ll likely be at band practice and hear, “Dude, what’s up? Your tone is killin’ these days!” Or maybe you’ll be at a gig, and some guitar geek will come up and say, “I love your tone! What are you using?” Or just maybe you’ll find yourself in the studio, and while the engineer is mic’ing up your rig, he’ll turn to you and say, “Man, your tone just nails the take. It records so well!” That’s the payoff of spending the time focusing on tone. But before your head explodes with that great feeling you get from other gear hounds checking out your rig, remember that you’re just getting started. Tone is a lifelong journey – just ask Eddie, Allan, Robben or Carlos. Happy hunting!

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)