Why is it that when soloing some notes that seemingly shouldn’t work, do? And no, it’s not jazz we’re talking about. So get ready to play some dissonant music that sounds wonderful.

Which Are the Wrong Notes?

For the purposes of this lesson, when we’re referring to “wrong” notes, what we honestly mean are “non-diatonic” notes–notes that are not in the home key of the chord progression. For instance, in the key of C major we have the notes C-D-E-F-G-A-B and the chords C-Dm-Em-F-G-Am-Bº. Thus, any notes not found in this collection are non-diatonic. As a result, this entire lesson will only use chords from the home key of C major, making the non-diatonic notes easier to identify. Respectively, I’ve also labeled the “wrong” notes as flats, even though sometimes they technically function as sharps.

Spice up Your II-Vs

When it comes to playing “wrong” notes, one of the best places to start is the old I-IV-V progression. While the tradition of the blues obviously fits into this category, I’m going to bypass that genre as there are plenty of other lessons focused on that idiom. Instead, I’m going to jump ahead to the blues’ babies–the first wave of rock and roll from the 1950s; its second wave, the British Invasion; the third wave of American garage rock; and ending with some rock/fusion.

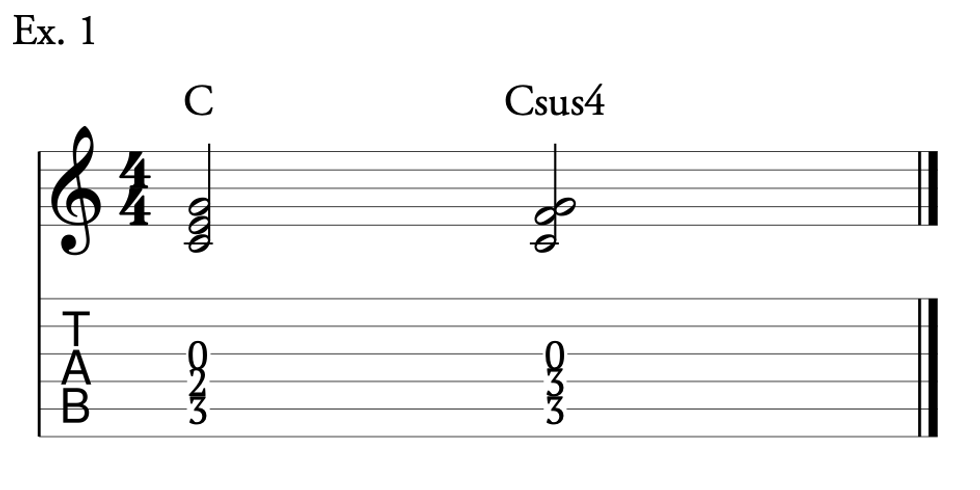

Though I am skipping traditional blues, the chord progression in Ex. 1 is in fact a 12-bar, but without the traditional blues riff. In fact, this feel is more akin to Gene Vincent’s “Be-Bop-a-Lula,” and the note choices are based on Cliff Gallup’s original solo.

To our 21st-century ears, most of this solo sounds normal, however, in the 1950s, many of these choices were radical to those raised on pop music. That’s because this solo is full of non-diatonic notes, specifically the b7, b5, b3, and b2, all of which can be seen in the notation by looking for the flat symbols. For example, measure one starts on a Bb, aka b7, measure two has a Gb, aka b5, etc. So keep your eyes and ears open for these non-diatonic notes.

One important piece of theory information here: When labeling notes as b7, b5, etc. it’s important to understand that these notes have two relationships, one to the overall key and one to each individual chord it’s being played over. For instance, a Bb is a b7 in the key of C and over a C chord, yet over the F chord the Bb is a 4. Additionally, over the G chord, the Bbis a b3. This can seem confusing at first but just think of it as a familial relationship: A daughter to a mother can also be a sister to a brother. It’s that straightforward: same person, two different relationships.

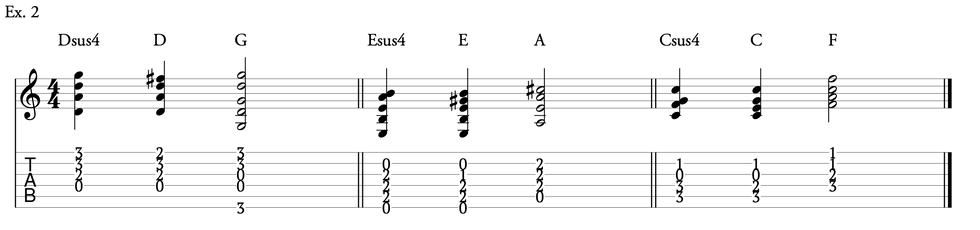

Ex. 2 is based on another I-IV-V 1950s rock and roll classic, Buddy Holly’s “It’s So Easy.” It would be understandable to presume that this example is merely using the blues scale, but this isn’t true. What this solo, and the entire lesson, emphasizes is that it’s the combination of both diatonic and non-diatonic notes that makes this lead so dynamic. Thus, this solo contains all 12 notes found in Western music! Even better, this solo also contains three so-called “quarter-step” bends (measures five and seven), which are not normally acknowledged in the traditional Western chromatic scale. A solo with 15 different notes… Amazing!

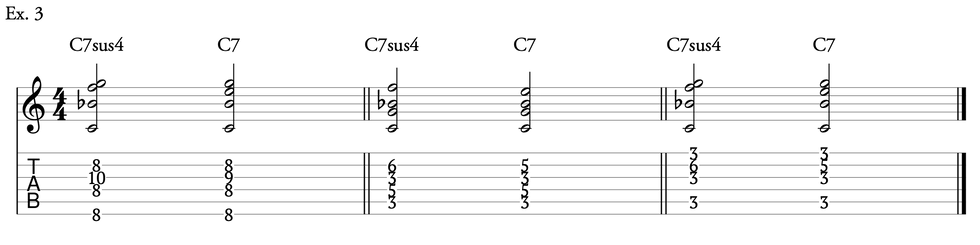

Moving on to a British Invasion era sample, Ex.3 contains non-diatonic notes in both the lead and accompaniment. At this point, it’s worth mentioning that many of the “wrong” notes are what we call chromatic passing tones, meaning we don’t spend a lot of time on these but pass through them on the way to diatonic notes. This can be seen and heard when the accompaniment moves from F to Gb to G, and throughout the solo. This lead also benefits from a “rhythmic motif,” meaning that the rhythm of the lead is consistent throughout the first three measures, which brings cohesion to the solo, and feels satisfying when measure four, surprisingly, varies the rhythm. This example is loosely based on “The Game of Love” by Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders.

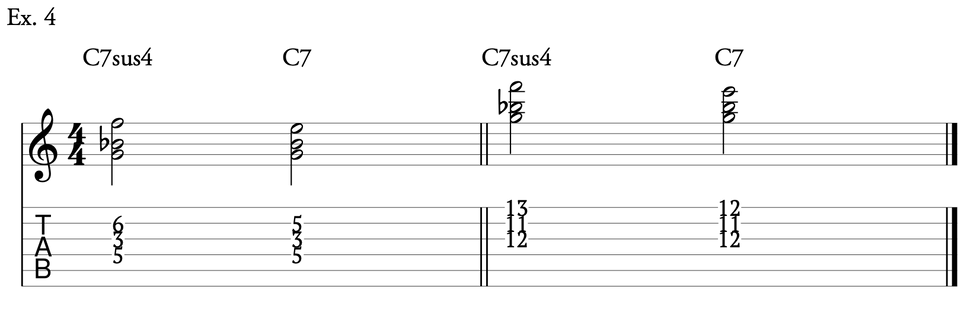

Ex. 4 is our final I-IV-V example, which was inspired by the McCoy’s garage rock-era cover of “Hang On Sloopy,” featuring a young Rick Derringer on guitar. This lead is almost entirely composed of double-stops, combining both diatonic and non-diatonic notes.

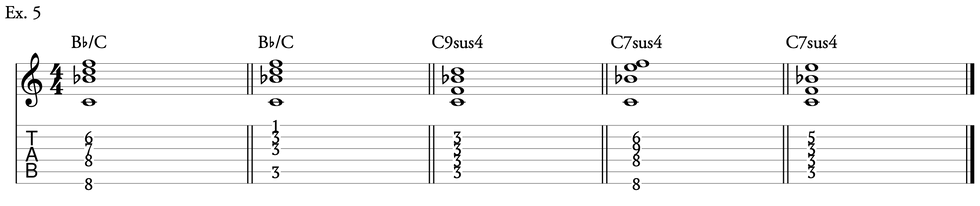

Mixolydian Hybrid

Returning to the British Invasion, countless songs from that era employ chord progressions that emphasize the Mixolydian mode, which is to say that they revolve around, and resolve to the V chord, instead of resolving to the I. The Them’s “Gloria” is a prime example. Hence Ex. 5, a Mixolydian hybrid–the progression is pure Mixolydian, the solo is not. While the original “Gloria” solo avoids non-diatonic notes, it does possess a rhythmic motif, which is a triplet figure comparable to the one in our example. As mentioned earlier, a rhythmic motif is a shrewd way to bring cohesion to a solo, even more so when using “wrong” notes. Ex. 5 abuses this privilege by running through a series of triplet groupings. Of particular interest are measures seven and eight, which contain a Db, which is extremely dissonant against the F and C chords yet still works wonderfully.

The Who also had their fair share of Mixolydian progressions (“I Can’t Explain” being perhaps the most famous) and Ex. 6 was inspired by their “Run Run Run,” featuring a solo by a studio musician named Jimmy Page. Unlike Page’s solo, which is largely pentatonic, this lead accentuates the differences between the various diatonic and non-diatonic notes.

Our final example, Ex. 7, is another Mixolydian hybrid inspired by both Jeff Beck’s “Freeway Jam” and Steely Dan’s “Reelin’ in the Years.” Once again we enjoy plenty of chromatic passing tones, and also noteworthy is the Gb, in measure four that wants to resolve to G but instead goes to B; and final descending triplets, which, as wrong as many of them are, find structure in their symmetry.

While there are myriad worlds of “wrong” note genres–20th Century classical music, free jazz, art punk, etc.–those are contexts in which wrong become “right” by way of stylistic intent. This lesson has attempted to demonstrate wrong notes in more pedestrian situations, circumstances in which an otherwise “normal” solo may be enhanced by spice, tension, and the unexpected. I hope you’ll attempt some of these ideas the next time you find yourself in a classic rock, country, or even folk jam…because wrong notes are alright!