Whether you’re a lead player looking add some fast-picked lines to your vocabulary or a metal player who wants to play faster riffs, you’ll need a solid foundation to tackle the heavy-duty alternate picking that’s needed. It’s always good to have that technical headroom to express yourself without hitting the ceiling too quickly. In this lesson, we’ll look at how “speed bursts” can help you with short- and long-term technique goals.

There is no “correct” way of picking. Picking techniques vary from player to player and there are some odd ones, like Marty Friedman’s approach where he bends his wrist at almost a 90-degree angle.

MARTY FRIEDMAN - MIRACLE (Official Video)

Notice how other players pick from different parts of their arm. Paul Gilbert’s picking motion comes mostly from his wrist, while shredders like Vinnie Moore and Rusty Cooley derive their power from their elbow. It’s not important how you do it, just make sure not to create excessive tension. Now, some tension is ok, but if your tone gets buzzy or you’re having trouble controlling the rhythm you should probably slow down and relax a bit more. This is a trial-and-error process, so it’s important to be honest with yourself and reflect on what your hands are doing. You’ll get a feel for how much tension is appropriate.

That brings us to the next important point about picking: rhythm. It’s all about being in time. At a certain speed—which is different for everyone—our brains stop processing each note individually and think of them as a group of notes. At slower speeds, our brain processes each note we hear before sending out the signal to play the next note. This is what neuroscientists call an open feedback loop, while fast playing occurs in a closed feedback loop, where our brain sends out the signal for an entire group of notes that is processed as one unit. That means that playing slow and playing fast utilize different neurological processes and the old adage of practicing slow to play fast doesn’t work.

Yes, you do need to first practice something slow to properly learn the phrase or lick, but once you have it under your fingers, you must crank up the speed and focus on the first note that falls on each beat and let your brain build up those note groupings. This is known as a speed burst. That’s why being in time and having good rhythm is so important for this process.

Practicing at fast tempos will also expose problems in your technique and efficiency that don’t show during slow practice. I’ve included some basic exercises first to help you really feel the rhythm of the right hand.

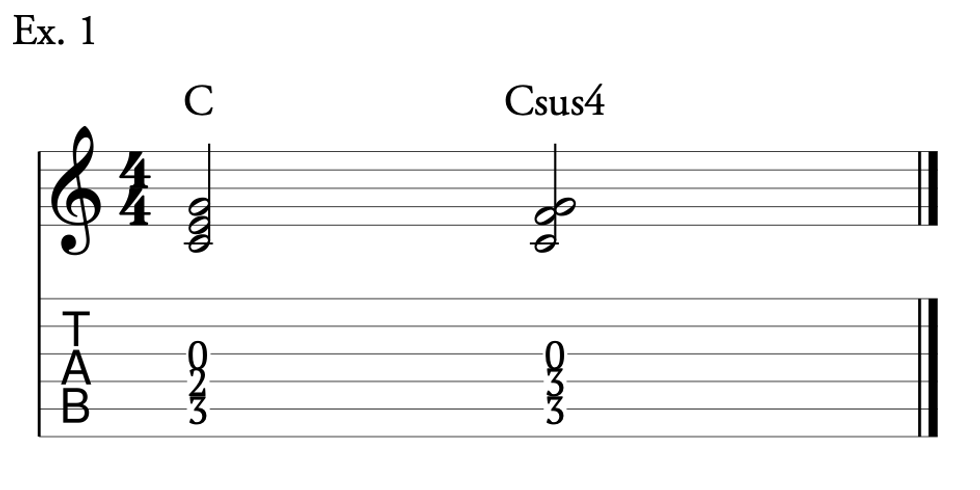

Ex. 1 introduces the idea of speed bursts. I’m playing 16th-notes on the first three beats of the measure and then one beat of 32nd notes. That will help you to get used to how it feels to play fast and dial in your right-hand technique with these short bursts. I play four measures of this and then take a short break so as not to fatigue my hand too quickly.

Ex. 1

Start at a comfortable speed and, once you get a feel for it, increase the speed in increments of about 5 bpm until the point where the burst starts to feel a little uncomfortable. At that point I’d recommend single repetitions and focusing on the rhythmic feel. Take short breaks between every repetition. When you feel comfortable at that speed, add more repetitions. When you can do four comfortably, bump up the metronome until it’s uncomfortable again. This forces your body to adapt to the speed and actually get better. You don’t get faster by staying in your comfort zone. Also, don’t do this while watching TV as some people recommend. Mindful practice reaps much faster results than noodling away while being distracted, by a TV or anything else. I also find being really focused on what you’re doing prevents getting bored quite effectively.

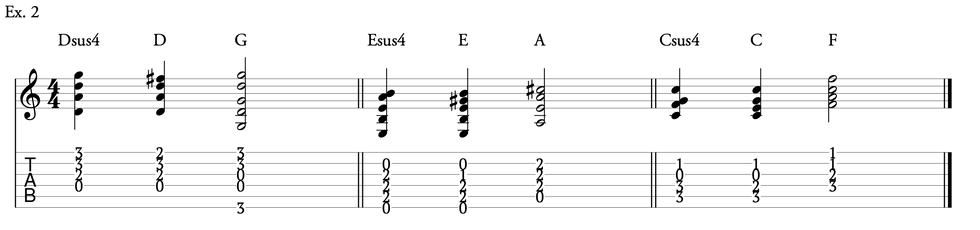

Ex. 2 does the same but adds a triplet feel for the burst, forcing you to focus on the rhythm and timing even more. I try to feel the sextuplet as two groups of three. Personally, this gives me more rhythmic control when applying fast picking to string changes as opposed to feeling three groups of two. Try both and see what feels better to you. There are never too many ways to feel a rhythm.

Ex. 2

I use a triplet feel throughout Ex. 3, flipping the picking direction every measure. You’ll start with an upstroke in the second measure and the burst in the second measure will reverse the picking pattern. Take it slow at first to really get comfortable with that and then follow the above procedure again. This is a great exercise to lose excessive tension and focus on your upstroke. You can and should of course also practice starting all the other exercises on an upstroke as well.

Ex. 3

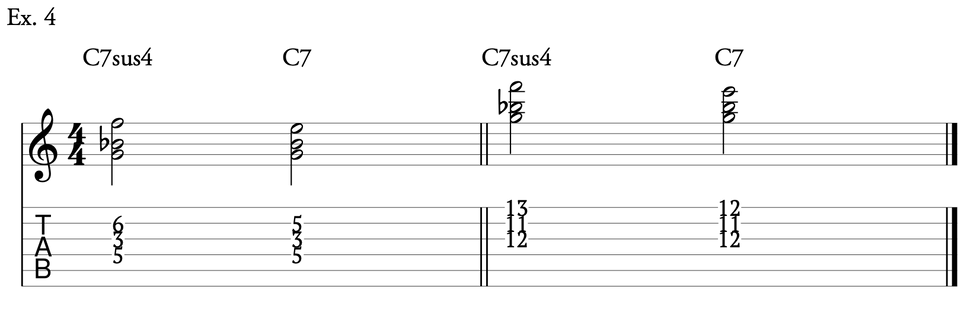

Ex. 4 is more for metal rhythm players who want to work on downstrokes at different subdivisions and then then add an alternate picked burst at the end.

Ex. 4

I use these first four examples as a right-hand warmup every day. Of course, there’ll be a point of diminishing returns once you hit certain speeds and you’ll reach that point rather quickly, which is why I focus most of my practice time on other aspects of my picking.

Let’s dive into some alternate-picking workouts. These are combinations of different short licks for you to work through. Practice each lick (marked by the letters in the notation) until you’ve got it under your fingers and then work through them back-to-back as a little routine. Start around 60 bpm and every time you get through about eight repetitions perfectly, bump up the speed. Once you start feeling uncomfortable, take a short break between every repetition. I prefer working through the licks in order because that improves your technique on a more general level and will translate better when you try to learn new songs or solos.

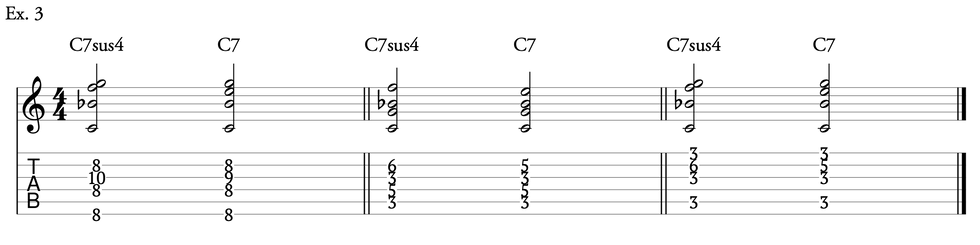

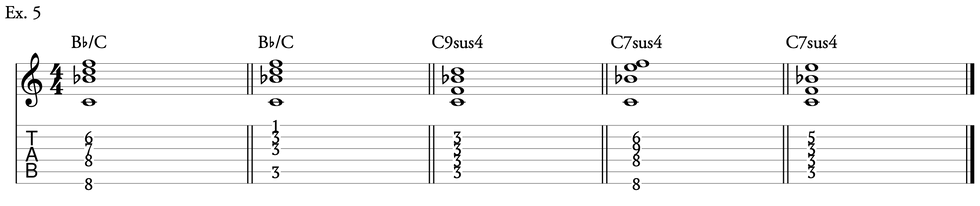

I usually spend about 25 minutes on one of those workouts building up speed. After staying at my limit for a few minutes I pick the lick that’s the least comfortable and lower the speed to where I can play it for about 30 seconds before I get sloppy. When you can play it cleanly without excessive tension for a full minute you can increase the speed there as well. If you comfortably hit 200 bpm or above, you can also start using 16th notes or sextuplets to work on different rhythmic feels. One you get comfortable with that you can even go up to 32nd notes to practice the feel of playing fast over slower beats. First up is Ex. 5, which focuses on eighth-notes. Once that’s in your fingers try Ex. 6, which works out a triplet feel.

Ex. 5

Ex. 6

Move these exercises to different scale positions and fingerings to mix it up. Also practice on different strings and with different tones so you can confidently play fast with clean and distorted tones as each one exposes different weak spots. Once you get those under your fingers you too will be praising the benefit of the burst.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)