Intermediate

Advanced

• Learn melodic minor scales

• Create melodic minor chord-voicing strategies

• Develop melodic minor melodic and harmonic vocabulary

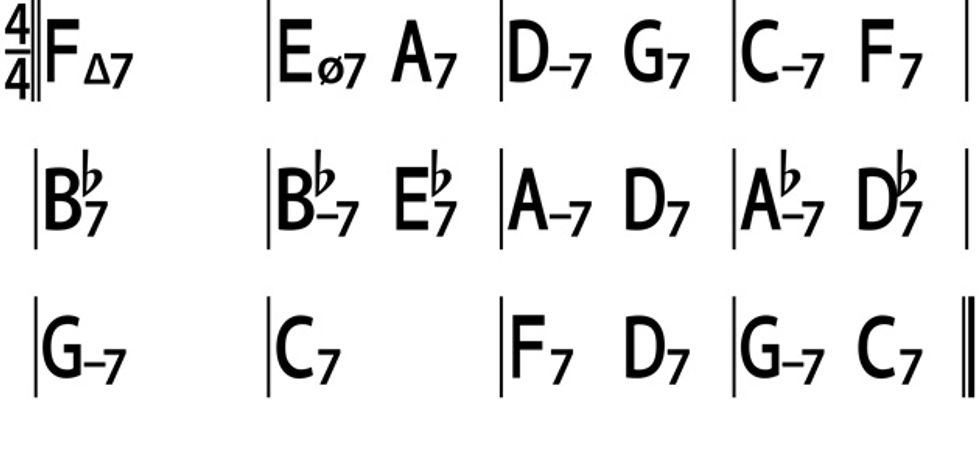

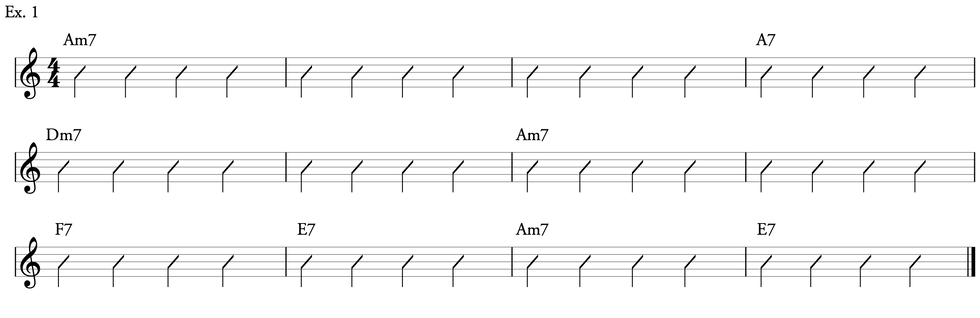

First, take a look at Ex. 1, which is the chord progression for an A minor blues. I will be referring back to specific locations in this progression from time to time.

Why is the Melodic Minor Scale so Bright?

Melodic minor scales are built with a W–H–W–W–W–W–W–H step pattern—W is a whole-step (two frets) and H is a half-step (one fret). The A melodic minor scale is spelled A–B–C–D–E–F#–G#–A, or 1–2–b3–4–5–6–7–8 in scale tones. (In classical theory, the melodic minor scale has a separate formula for its ascending and descending forms. For our purposes—as is often the case in jazz—we’re using the ascending form for both directions, not the descending form, which would be the same as an A natural minor.)

It sounds bright because its structure yields an abundance of whole-steps in the upper part of the scale. Take a listen to Ex. 2 to hear how it sounds against an Am chord. You can use this scale anywhere you see an Am chord in Ex.1. Measures 1–3, measures 7–8, and measure 11.

Since this scale has a natural 7, or a leading tone, it makes the Am chord sound like tonic minor. Basically, this scale tells everyone, “Yo! We’re in the key of A minor!”

Consider the bVI chord—F7—in measure 9. This is an opportunity to use F Lydian Dominant, which is the fourth mode of the melodic minor scale system. It is built with a W–W–W–H–W–H–W step pattern, spelled F–G–A–B–C–D–Eb–F, and its scale tones are 1–2–3–#4–5–6–b7–8. When using this mode, you’re implying that your F7 chord has become an F7(#11). Since this scale is the fourth mode, the parent scale of F Lydian Dominant is C melodic minor. Listen to Ex. 3 and hear how the F Lydian Dominant mode sounds over an unaltered F7 chord.

Let’s talk about dominant function chords.

The actual V chord in the key of A minor is E7, and it’s found in measure 10. There is also a secondary dominant in measure 4. A7 is functioning as the V chord in the key of D minor and provides some forward motion, making it sound like you’re headed to a new key. The seventh mode of the melodic minor scale system is Super Locrian, and you use this mode to get a fully altered dominant chord sound. For E7, you play the E Super Locrian mode, which is built with a H–W–H–W–W–W–W–H step pattern, spelled E–F–G–Ab–Bb–C–D–E, and its scale tones are 1–b2–#2–3–b5–#5–b7–8. Using this mode over a dominant chord gives you both altered 9s and altered 5s, turning E7 into an E7alt chord.

The method is the same for A7, where you would use the A Super Locrian scale to achieve an altered dominant sound, creating more musical tension that can be resolved when you land on the tonic chord. Listen to Ex. 4 to hear each of these Super Locrian modes played over their corresponding unaltered dominant chords. Again, remember that the parent scale of E Super Locrian is F melodic minor, and the parent scale of A Super Locrian is Bb melodic minor.

So, what does this sound like when you put it all together?

Ex. 5 is one possible solo, blending traditional minor pentatonic sounds with the melodic minor scale. The lines are also not too heavy on altered sounds over the dominant chords.

Ex. 6 leans into the melodic minor scale and the altered sounds more, arriving at Ex. 7 which is more angular and rhythmic.

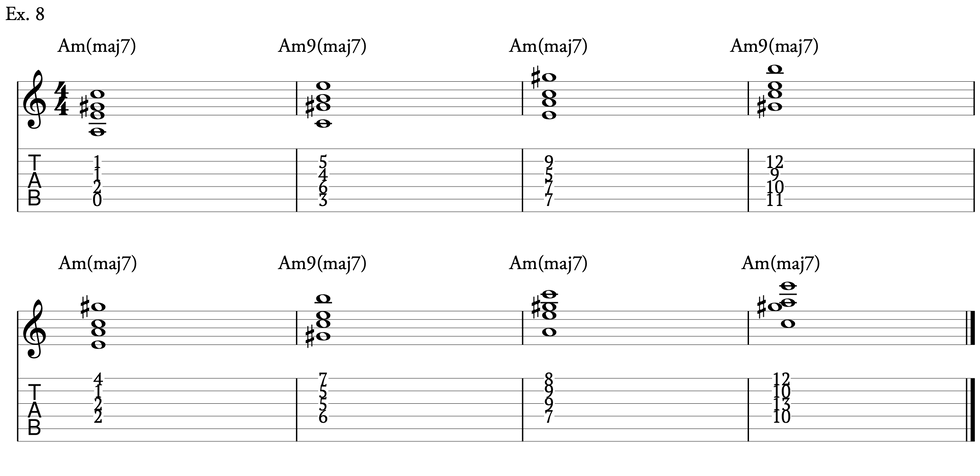

There are two paths to creating chord voicings for these altered sounds. One way is to take the unaltered seventh chord, find all your altered 9s, 5, and 11s, and adjust the shape. The other way is to simply use the min(maj7) chord of the parent scale. Take a look at Ex. 8 for some Drop 2 min(maj7) voicings and inversions. Substituting Amin(maj7) for Am or Am7 should be pretty straightforward, keeping in mind that a major seventh chord will sound kind of bright. For your F7(#11) sounds, use a Cmin(maj7) chord voicing, where C–Eb–G–B will sound like the 5, b7, 9, and #11 of F7.

To get the altered dominant sounds, play an Fmin(maj7) chord instead of E7, where F–Ab–C–E will sound like the b9, 3, #5, and root of your E7 chord. The same relationship holds for A7, where you would use a Bbmin(maj7) voicing to get an altered chord sound. In Ex.9, you can hear how these voices are working against a bass line.

There’s a lot to unpack here, especially if you’re not familiar with all the modes of the melodic minor scale system. Learn the modes, then start with simple, straightforward musical ideas. Just going up and down the mode will get these new sounds in your ear, and using traditional structures like thirds, triads, and arpeggios will give you something to play without feeling overwhelmed. Welcome to the bright side of the blues!