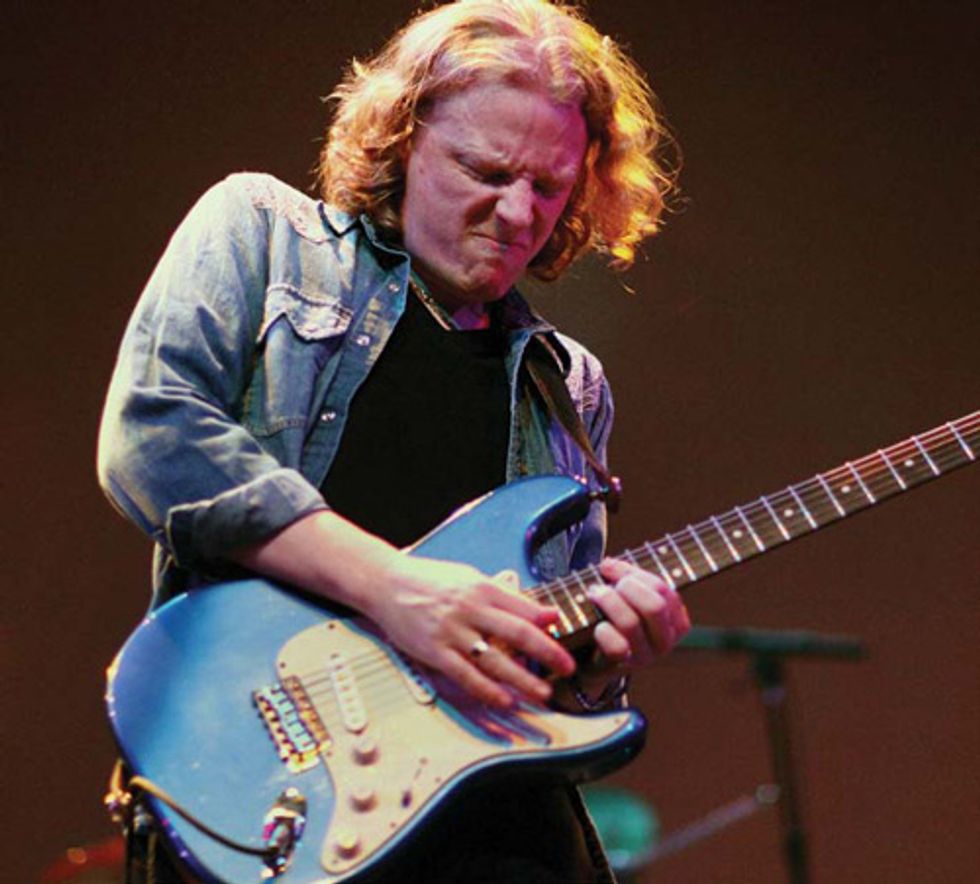

which has three custom-wound Amalfitano pickups. Photo by Ron Boudreau |

Earlier in the evening, he had a CD-release show next door at the Rockwood Music Hall. While most blues aficionados would say exotic- sounding cocktails and high-maintenance blondes are about as far removed from the blues as you can get, there’s no questioning Schofield’s cred as a blues artist. For years, he’s been one of the most buzzed-about up-and-coming blues guitarists, and his last album, Heads, Tails & Aces, won a 2010 British Blues Award for both best British Blues Guitarist and best British Blues Album.

Schofield’s latest release, Anything But Time, marks several firsts for the young blues sensation: It’s the first album Schofield has recorded in the States, it’s the first album with his new band, and it’s his first album with an outside producer— blues legend John Porter. Having already amassed heaps of critical acclaim—including our 4.5-pick review [July 2011]—Anything But Time is poised to catapult Schofield into blues superstardom.

Tell us about the new album.

It was recorded in New Orleans and is the first album with this new lineup, which features Kevin Hayes on drums. He was with Robert Cray for 18 years, so I’d known his playing for a long time. We met at a festival he was playing with Robert in Holland a few years ago, and he gave me his card. So we came out here last year to start touring, and Kevin joined us then. What started as a few gigs with him evolved into this current band. Then we thought, “We need to make a CD of this.”

This is your first album with an outside producer. What was it like working with John Porter?

I grew up listening to records he made, and he’s made like 150—he did Buddy Guy and B.B. King and Otis Rush—so I could really trust him on it. We kind of have the same reference points, even though we’re from a different generation of music. I thought, “I’m just going to go with my ideas and he’s going to say if it’s good or not.” When we first met, he said something that stayed with me. He said, “I think we’d have a lot of fun making a record.” And I never had fun making a record—it’d always been really stressful.

Some guys are into putting a sonic signature on a record—that’s the way they produce. They give you their sound. John is quite the opposite. He’s very transparent, sound-wise. He gets in on the material and works on the arrangement with you—really trims the fat off the arrangements. I couldn’t have done it this time without him.

I’ve done all of my other records myself—I produced them and mixed them with an engineer. This time, I decided I was going to do the exact opposite and be totally hands-off. I was just going to play guitar and sing, and I was going to let John do his thing. So maybe next time I won’t be so hands off, but it was kind of like an experiment for me to see if I could.

Were you happy with the results?

Yeah.

What gear did you use on the album?

I used my old ’61 Strat and the new Daytona Blue SVL 61—which matches a late-’60s Ferrari Daytona—on about the same amount of tracks. I also used an ash-bodied hardtail SVL 59 with custom-wound Amalfitano pickups a little bit—I’m really getting into that now. I’m more familiar with the blue SVL 61—which is based on my original ’61 Strat and has an alder body, maple neck, Brazilian ’board, 6100 frets, and Suhr FL Classic pickups. The 59’s ash body has a slightly different sound. Simon [Law], who makes SVL guitars, was just trying to get as close to my old Strat as possible. He had some Brazilian fretboards—I don’t think you can get them anymore—and he used those because my old Strat’s got them.

Matt Schofield onstage with his trusty SVL 61. Photo by Sam Charupakorn

What about amps?

I use a 50-watt Two-Rock amp based on their Classic Reverb model, but it’s tweaked up for me. They [Two-Rock] changed the midrange voicing a bit. It has two rectifiers, so it’s punchy like a solid-state amp, but feels nice. It doesn’t get all mashy and saggy like amps with a tube rectifier.

You’ve mentioned in the past that a blackface Fender is the tonal ballpark for you. Why not just use one?

I do use a Super Reverb, but things have evolved a lot more than that. The Two- Rock reminds me of my blackface Fender in that it does everything I like but it’s much bigger, fatter, and more reliable. It never breaks down. With the 4x10 cab that they make for me, it’s kind of like a giant-sounding Super Reverb—but with that midrange that the Two-Rocks get, as well.

What else can you tell us about your Two-Rock?

It’s a single-channel amp, and I use it for the clean sound and then get the dirt from my pedals. But I totally rely on the tone of the amp in the first place—it’s not like I’m using a lot of gain on the pedals. It has a bunch of other switches and functions that I never use—like the FET boost channel and all the switches on the back that I never know how to set—but they’ve been taken off or disconnected.

I understand that you’ve also recently checked out some Bludotone amps.

Simon looks after one for Larry Carlton in the UK—Larry keeps them all over the world—so I got to use Larry’s for a few shows. It’s really cool, but definitely more of that Dumble thing, and I’ve gone back to using a single-channel clean amp.

So now, even if you had access to an actual Dumble, you’d still be using the Two-Rock?

Yeah. With the latest stuff Two-Rock has been putting out, I’m, like, totally done with gear. I’ve got the Two-Rock and the 4x10 cab with the Eminence Ragin Cajuns, and they work every night—they never blow up. And I’ve got my two pedals—the Klon [Centaur] and the Mad Professor Deep Blue delay. I’m not even looking for gear anymore.

Is there any other gear you’re really ecstatic about?

I have my own signature set of Curt Mangan nickel-wound stings, and they’re the best strings ever for me. They sound great, and I haven’t broken a single string since I started using them. I’ve even been able to go back to using vintage-style steel saddles on my guitars, which I much prefer the tone of over graphite “string-savers.”

Schofield with organist Jonny Henderson (left) and drummer Kevin Hayes (right).

There are two cover songs on the album. How did you choose those?

When Kevin joined the band he said, “Have you guys heard that recent Steve Winwood record? There’s a good tune on it we should try doing.” And it turned out that me and Jonny [Henderson, organist] had already been playing it, so we were like, “We gotta do it now.”

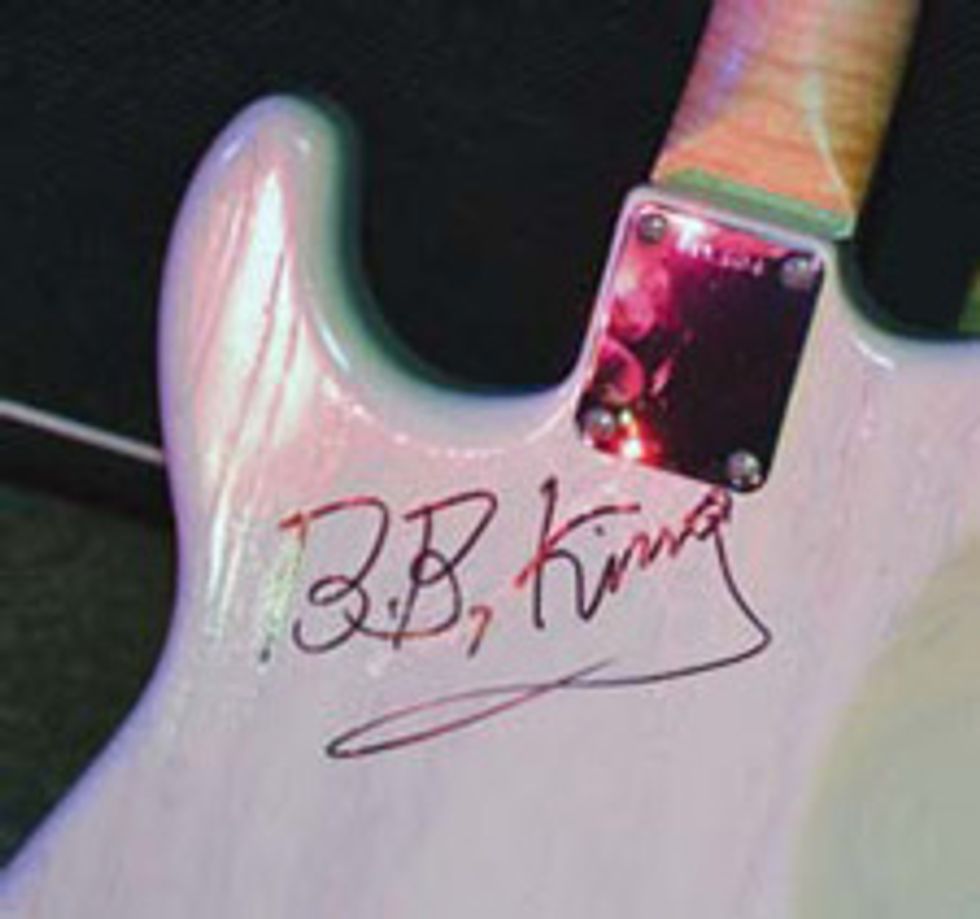

I have a big, long list of songs I’ve been doing since I was a kid, and every time we do a record I get to do one. On the last record we did a Freddie King tune, on the one before that we did a B.B. [King] tune, so this time it was Albert [King’s “Wrapped up in Love”].

Were you channeling your inner Hendrix on “Dreaming of You?”

For a long time, we were kind of known as the jazzy blues guys—certainly in the UK— with what we were doing with the organ-trio stuff, but there’s, of course, a whole other side to me with Hendrix that I’d not really brought out [before]. So this seemed like the right time to do that.

“Share Your Smile Again” has an almost pop sound.

|

Is that a direction you may consider?

No, it’s always going to be what it is. For me, it’s like, if we’re doing something a bit poppy, it’s because I like poppy stuff, as well.

If you went and got an A-list celebrity girlfriend and made the tabloids every day, that wouldn’t be so bad, would it?

I don’t know whether that feels good to me though, y’know? If it meant I couldn’t turn around and do what I do already.

So you wouldn’t compromise?

No. But there’s no great master plan for me, like, “I gotta make it more poppy.” It might be like, “All right, we’re not gonna do a bunch of Meters-like instrumentals.” But it’s not, “Are we gonna do a John Mayer record?” And I think John’s fantastic—his Continuum album is fantastic. But that’s not for me. Everything that we do, you’re going to cheer or smile when it gets to the outro—it’s blues time for me.

Your vocabulary is broader than the typical minor-pentatonic-based blues player. Do you have to edit your playing to conform to the expectations of typical blues fans?

The only person I try to hold back for is me. My own sense of taste is what determines what I do. Sometimes it starts coming out and I could just keep going and going and going, but I think, “You know what, nobody wants to listen to that—including me.” That’s the edit point.

We played at a jazz festival last night, and a lot of the people came up afterwards and said, “We enjoyed it so much tonight because it was easy to enjoy—it was accessible.” That’s the bit I always try to keep in mind. I just want people to be able to enjoy it as well, because if I go to a gig I want the same thing for myself. The other night we went to see Oz Noy in New York—unbelievable guitar playing. And it’s a thrill for me to hear someone and have no idea what he’s doing at all, because I don’t get to see that very often—where it’s like, “What the hell is this guy doing? ” But it’s not accessible in anyway—which is great, if that’s what you want. But that’s not what I want for my music.

Virtually every electric guitarist can play the blues to some degree. What differentiates a great blues guitarist from the pedestrian?

To me, it’s melody. If it’s lots of notes or not many at all, melodically it has to makes sense and fit with the music. Unfortunately, what a lot of blues-rock guitar playing became at some point is a bunch of pentatonic over whatever was happening. If you listen to Albert King or B.B., it’s very simple playing—especially Albert—but it works. And they’re actually making the chord changes in their own little, simple way.

I don’t think the blues is in the notes, I think it’s in the way you play—the feeling and the timing and the phrasing. To me, those rules apply no matter how technically advanced you become.

When you go from playing intricate lines to pentatonic licks, it sounds really organic. Was it hard to integrate the jazzier lines into a blues context at first?

Probably a little bit. But it was always about sounds to me. It was never like, “I learned a scale.” I never sat down and went “this is a scale.” It was a sound that contained those notes within it that I heard somebody do and then I found that sound. Then, afterwards, I found somebody who knew more about it. Like Jonny, who has much more theory knowledge than me, would say, “Oh, that’s a Mixolydian thing.” I really don’t know that much of what I’m doing.

Schofield lets the G string on his SVL 61 sing. Photo by Jim Nichols

People have compared you to Robben Ford. Did you transcribe his solos when you were younger?

I get compared to him a lot. It was a major life-changing experience when I saw him live for the first time. But the biggest influence he had on me was in his approach. He was the first person I had heard play in that way. It was like, “Wow, that’s what I wanted to hear.” It fit what I was doing or what I was trying to do, and then it was like, “Where’s he getting that from?” But really I never transcribed anything, I figured out a couple of licks from Robben and thought, “Oh, that’s how he’s getting around that.”

There’s one lick that Robben played in his song called “Misdirected Blues” and I’d never heard anything like it over a 12-bar shuffle—it’s an incredible lick. So I figured that one out and that single lick opened a door for me. I never felt the need to learn the rest of it. You figure out the basis on which something works, and then you know how to do it yourself. I learned how to play the pentatonic scale from the pentatonic thing in the intro of “Voodoo Child,” but I didn’t know what the pentatonic scale was—it was just a sound. Then I thought, “Okay, well if I play that with some bends and vibrato and stuff it sounds like other blues stuff.”

Is singing an important part of your success? Would you be as successful if you were just a guitar player?

It’d probably be difficult.

Is it possible?

Well, Derek Trucks has done a fine job of it. He’s a monster player.

Absolutely. But he’s also got the Allman Brothers legacy.

It does change things, that association. It’s hard to know, because in the beginning singing for me was like, “Well somebody’s got to do it.” All my heroes—guys like B.B. King, Freddie King, Albert Collins, and Albert King—they were the entire package. They were entertainers—they sang, they played, and they had the tunes. It’s more important to me to get good at singing and writing songs and all that stuff. I think about that more than guitar playing now.

Photos by Jason Shadrick

Matt Schofield's Gearbox

Guitars

1961 Fender Strat, Daytona Blue SVL 61, SVL 59 hardtail, Tele-style SVL Custom Deluxe (below)

Amps

Two-Rock Classic Reverb 50 with dual GZ34 rectifiers and 6L6 power section, Two-Rock 4x10 with Eminence Ragin Cajun speakers (live), Two- Rock 2x12 with Two-Rock spec Eminence and WGS speakers (studio)

Effects

Providence SOV-2 Overdrive (“My favorite overdrive ever”), Klon Centaur (for clean boost), Mad Professor Deep Blue Delay (“It’s always on, but barely audible—set just longer than a slapback for a bit of extra ambience”), Mad Professor Forest Green Compressor (studio), Providence Final Booster (studio)

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Curt Mangan Matt Schofield Signature strings (.011, .014, .018, .028, .038, .054), 1mm Curt Mangan Curtex picks, Sonic Research ST-200 Turbo Tuner, Providence cables (E205, S102, and P203 models)

SVL Guitars’ Simon Law on Schofield’s 6-strings

“I have known Matt for many, many years, and I’ve always known him to be a real player—a real tone guy,” says Simon Law of SVL Guitars in Gloucestershire, England. Law has worked as Schofield’s guitar tech since 2006—the same year the two began discussing building a guitar that Schofield could take on the road instead of his precious 1961 Strat.

“Matt is such a killer guy to build and mend stuff for, because he gets it: He plugs the guitar straight into the amp and it sounds like Matt playing a good guitar through a good amp. He’d sound good with a Squier Strat and a solid-state amp. However, give him a good guitar and amp, and he sounds like a million dollars.”

Photos courtesy of SVL Guitars

“His ear for what makes the difference was obvious to me from the start,” Law continues. “I had built a Tele-type guitar called the SVL Custom Deluxe, which is an ash-body hardtail with two mini humbuckers—an absolute killer guitar. He used the guitar when he played with Ian Siegal at the North Sea Jazz Festival that year, and later he told me what he liked about that guitar and what he didn’t like. I made notes on nut width, neck radius, and profile, etc., and the next year I made the first SVL 61 in Vintage White with a flatter Brazilian [rosewood] fretboard. He really dug it, but it just wasn’t quite right for him. I realized I was going to have to dig deeper.”

It took a few more prototypes before Schofield was happy, with each one getting closer and closer, “until I cracked the vintage code a couple of years ago with his SVL 61 in Daytona Blue (above middle). That guitar was just right for him—I even measured the exact neck-pocket depth to make sure his pickups could be set the same as on his old ’61 Strat. The contours are bang on, and even the feel of the neck. It took me about a year to build, but he bonded with it instantly and has played it ever since. I have built him one more guitar since, his SVL 59—a one-piece, ash-body hardtail with custom-wound Amalfitano pickups (above left and right). Up until this one, he had been using the Suhr Fletcher Landau Classics.”

As for the setup of Schofield’s guitars, Law says they’re pretty straightforward. “He’s got medium-high action with .011–.054 Curt Mangan strings. I also fit his guitars with Oak Grigsby double-wafer switches so his tone controls are not in the circuit at all when he’s using the in-between sounds—it makes for a way funkier-sounding guitar.”

Asked what new things are in store for Schofield’s rig, Law says, “I’m currently building something else for him, something more like an old SVL 61 that someone has stripped and waxed—a real tone guitar with almost no finish on it. Hopefully, you’ll be seeing this guitar out pretty soon.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)