Have you ever asked yourself if you “know” all your scales? Well, one might answer that question with the chromatic scale. Simply put, the chromatic scale is all 12 notes. Chromaticism plays an important role in the construction of melodic lines in jazz, allowing dissonance to resolve into consonance. Jazz players are fond of a famous quote that basically states: No matter where you are on the neck, if you hit a “wrong” note you’re only a half-step away from a “right” one. This lesson will show how to integrate chromatics into major and minor CAGED scale forms, as well as provide examples of jazz lines. While this lesson centers around a major scale, this method of visualizing chromatic scales works with all scale types.

Let’s begin with a fingering for a chromatic scale. Ex. 1 shows an ascending and descending one-octave chromatic scale in open and first positions. We’re starting on C, so I used a Cmaj7 chord as the underlying harmony.

Ex. 1

Let’s expand that idea in Ex. 2. Here we are starting on F and playing a chromatic scale up to the A on the 1st string before descending to where we started. Because we aren’t using any open strings, this fingering can easily be moved up and down the neck.

Ex. 2

To clearly see how to integrate the chromatic scale into the major scale forms, I believe it’s best to start with one-octave major scale fingerings. Since we want these to be movable all over the fretboard, I’ve written them in 2nd position to avoid any open strings.

Ex. 3 is based on the “A” shape in the key of C.

Ex. 3

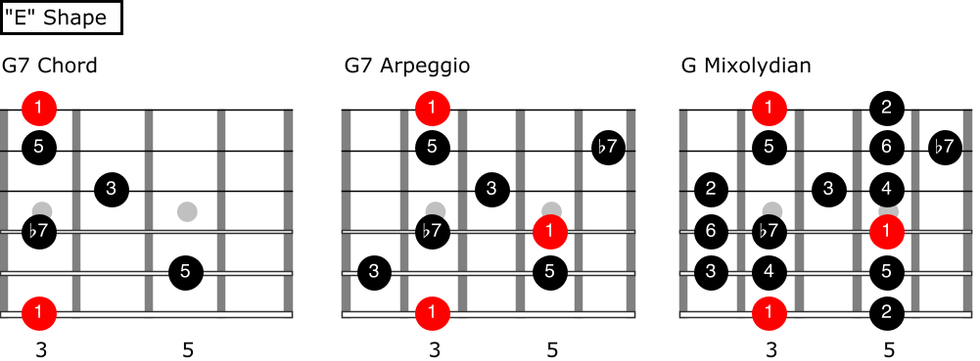

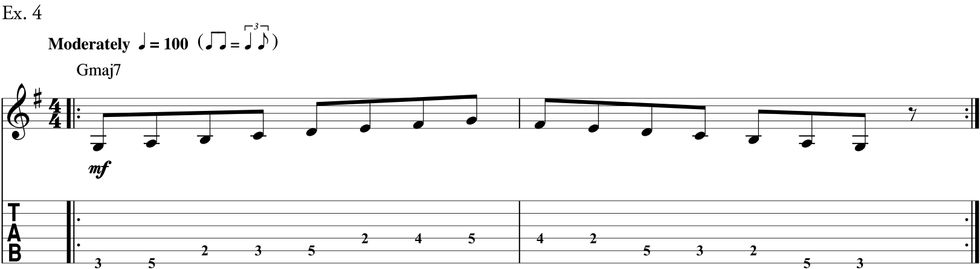

Ex. 4 is based on the “E” shape in the key of G.

Ex. 4

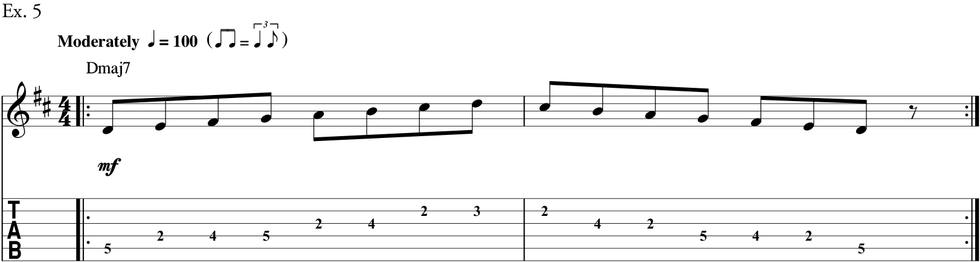

Ex. 5 is based on the “C” shape in the key of D.

Ex. 5

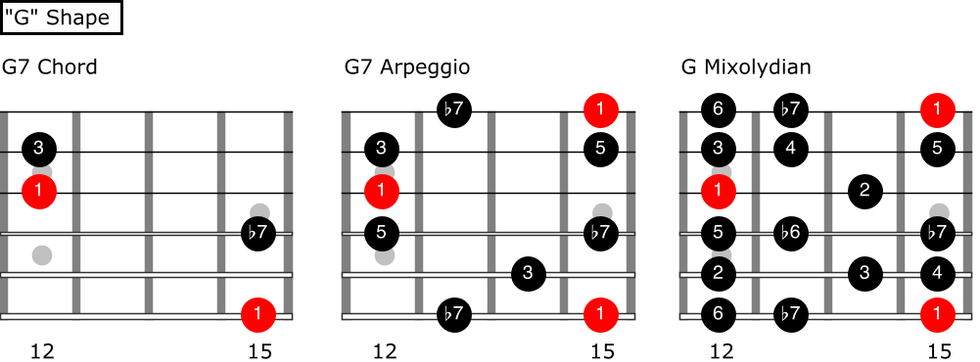

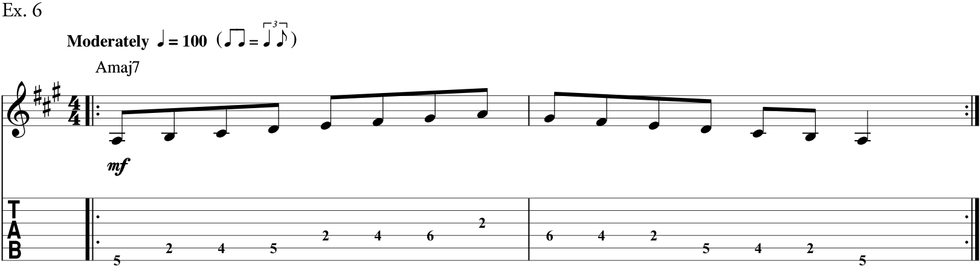

Ex. 6 is based on the “G” shape in the key of A.

Ex. 6

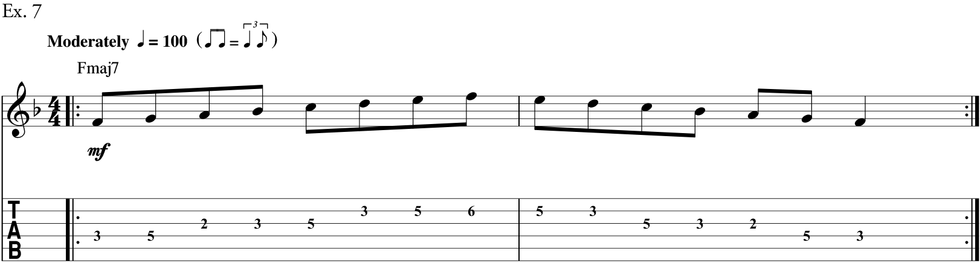

Finally, Ex. 7 is based on the “D” shape in the key of F.

Ex. 7

Now that we have our scale forms, let’s add in the chromatics by filling the spaces between the diatonic major scale tones. There are two possible fingerings for the chromatic scales derived from these forms, due to the guitar’s tuning. The following group of examples illustrates these fingerings.

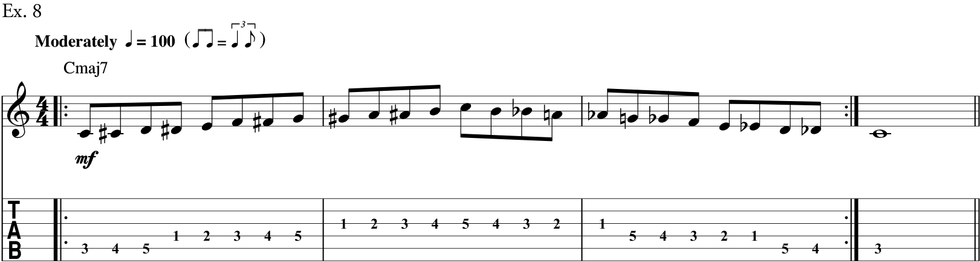

Ex. 8 is based on the “A” shape in the key of C.

Ex. 8

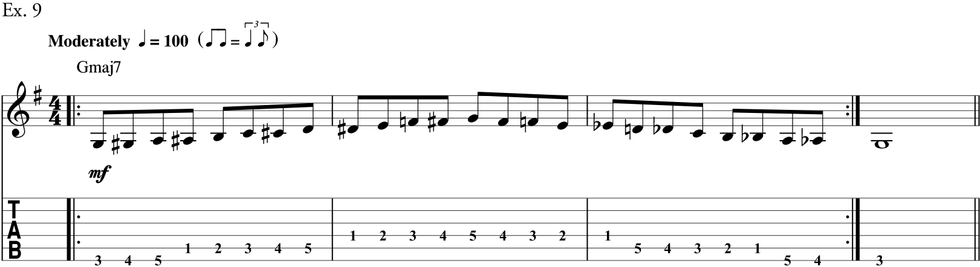

Ex. 9 is based on the “E” shape in the key of G.

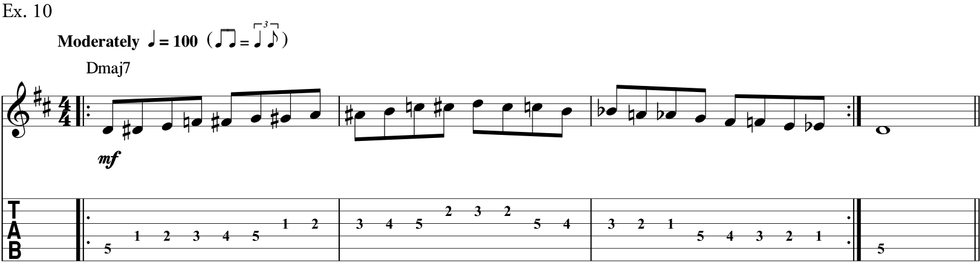

Ex. 10 is based on the “C” shape in the key of D.

Ex. 10

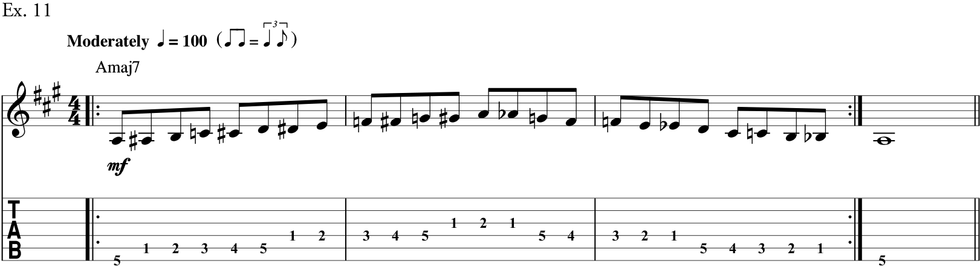

Ex. 11 is based on the “G” shape in the key of A.

Ex. 11

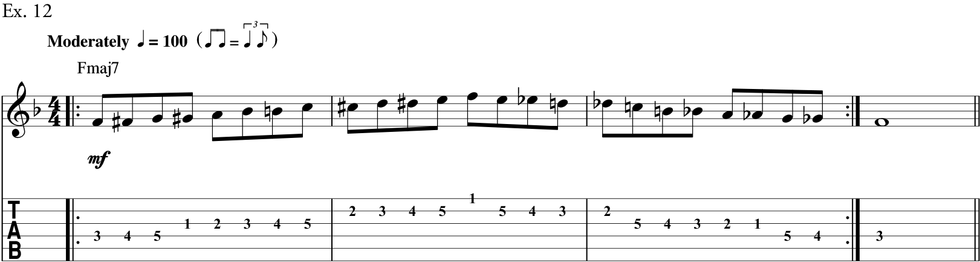

Finally, Ex. 12 is based on the “D” shape in the key of F.

Ex. 12

Generally, melodic lines are constructed using a balance of scalar and arpeggiated movement. Think of chord tones (root, 3, 5, 7) and the extensions (9, #11, 13) as areas of resolution. Chromatic passing tones are initially inserted between whole-steps, allowing connections and resolutions to chord and scale tones.

In measure one of Ex. 13, Ab is inserted between A and G, allowing a descending chromatic passage. Also, note the Eb inserted between E and D. Most of this example makes use of this device.

Ex. 13

In Ex. 14, I’m using mostly descending chromatic passing tones, but observe the ascending chromatics in measures one, two, and four. I briefly hit a C# in the first measure. Normally, I would resolve to D. Instead, I skip to E and then descend chromatically to D.

Ex. 14

By now, these chromatic devices should start to sound familiar to your ear. In Ex. 15, I’m pretty much sticking to ascending and descending chromatic movement.

Ex. 15

Ex. 16 balances the ascending and descending chromatic movement. Notice the four-note motivic sequence in measure two.

Ex. 16

Ex. 17 starts off with a very cool way to skip between two chord tones. In this case, we move from the root (F) to the 7 (E) and then descend chromatically to D. From there we skip up to the root and then leap down to A before approaching the root chromatically from G. When you start to isolate and analyze the nuances of these lines, they become easier to integrate into your own playing.

Ex. 17

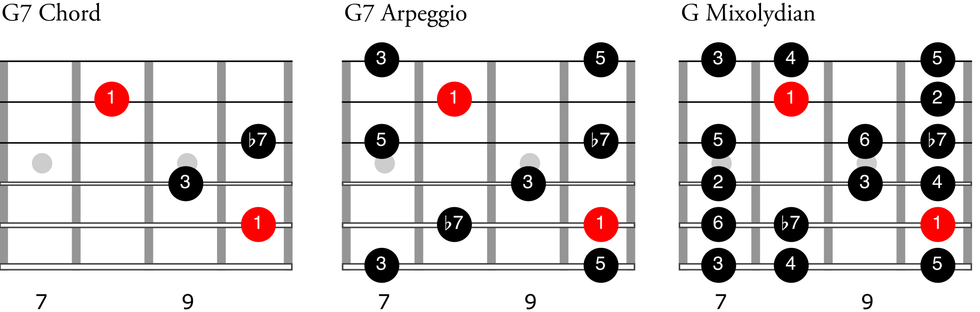

Once you understand the basics of integrating chromatics into a one-octave major scale form, then you can apply those same principals to the full CAGED fingerings. Ex. 18 shows each fingering.

Ex. 18

Ex. 19 illustrates how to expand the full “C” shape to include all the chromatic notes.

Ex. 19

Ex. 20 expands on the “A” shape.

Ex. 20

Ex. 21 expands on the “G” shape.

Ex. 21

Ex. 22 expands on the “E” shape.

Ex. 22

Ex. 23 expands on the “D” shape.

Ex. 23

Ex. 24 expands on the “C” shape in closed position.

Ex. 24

The following examples cover the full range of the scale forms. All of the examples are over a major 7 chord quality.

Ex. 25 makes a straight-ahead use of ascending and descending chromaticism. To avoid turning your line into a total chromatic passage with no whole-steps, it’s important to balance diatonic and chromatic movement. Of special interest in this line is measure four, which leaps from G to E to G and follows with an ascending chromatic approach to A.

Ex. 25

In measure one of Ex. 26, notice the chromatic descent from A to G. This is followed with an ascending Gmaj7 arpeggio. The rest of the line is made up of various ascending and descending chromatic movements. A special moment occurs in measure four, where D skips to Ab and then moves down to F# before resolving on G. The G is therefore approached chromatically from both above and below, which is called a double-chromatic approach.

Ex. 26

Ex. 27 kicks off with almost a boogie-woogie pattern. When it gets to A, a skip occurs from A to C# (root to 3) and then moves to a chromatic descent from B to A. Similarly, a skip in measure four moves from D to E before resolving chromatically to D.

Ex. 27

There’s more sequential writing in the first measure of Ex. 28. The first two beats establish a bit of a chromatic motif that catches the ear. Measure three uses one of my favorite chromatic devices, where on beat 3 you skip up from a root to a 5 and then drop to the 7 and descend chromatically as little or as much as you want. In this case, I went chromatically from G# to F#.

Ex. 28

Finally, we have Ex. 29. If you’ve made it this far you must really love chromatics! We kick off with a downward leap from the root to the 3 before ascending chromatically to the 5. Always try to keep chord tones on the strong beats, as this will help give your lines focus and direction.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)