Dynamics are one of the simplest concepts in music. The term merely means how loudly or softly a section of music is played. But like so many things in music and life, it’s less complex in theory than in practice.

This lesson explores dynamics from extreme quietness to extreme loudness with the goal of adding drama and nuance to your playing. It’s got to be a good idea to maximize your dynamic range, right? That way you have the greatest possible range of expression. But there are some musical situations—busking in a subway tunnel, say—where you want to keep everything as loud as possible. Different strokes for different … gigs.

Playing vs. Drawing

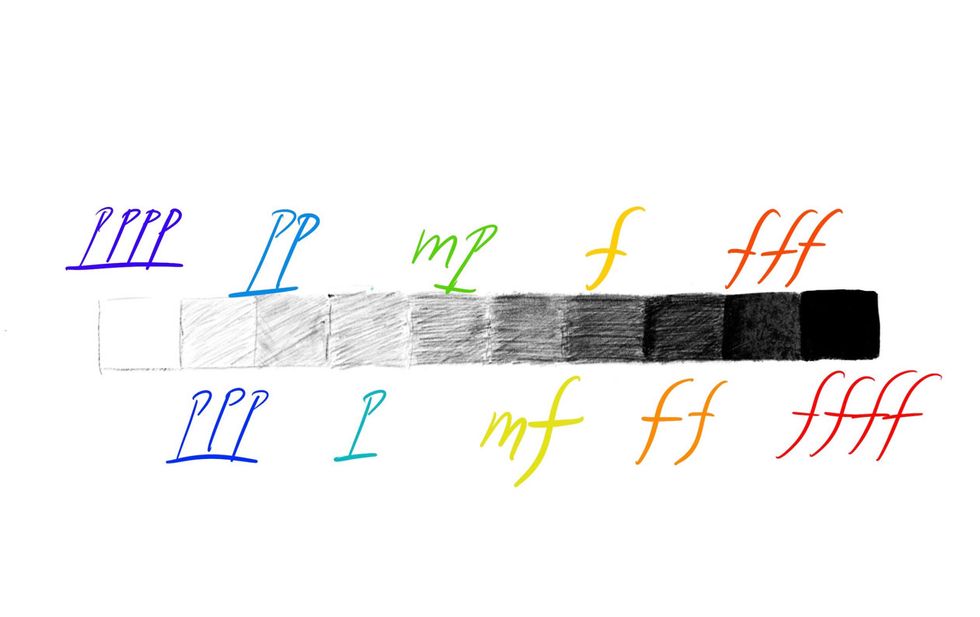

It’s useful to think of dynamics the way a visual artist thinks of light and dark. A common exercise in drawing classes is to sketch a row of boxes, leaving the first box unfilled so the pure white paper shines through, and filling the last box with the darkest black your pencil permits. Then you fill in the boxes between, creating a graduated light-to-dark scale, as seen in Fig. 1.

I’ve drawn ten boxes to correspond to a number of possible dynamics indications in traditional music notation, which I’ve scribbled in around the boxes.

Levels of Loud

You don’t need to read music or know music theory to understand traditional dynamic symbols. (Skip ahead if you know this stuff.) They’re all based on the Italian words forte (for loud/strong) and piano (for soft). That’s f and p in shorthand.

It didn’t become common to indicate dynamics in musical notation till the 18th century (though there are a few earlier examples). Originally only p and f were used. Then composers started adding pp (very soft) and ff (very loud), along with mf (for mezzo forte, which means medium loud) and mp (medium soft).It became a dynamics arms race: Beethoven popularized ppp and fff, and by the end of the 19th century post-Romantic composers employed pppp and ffff. Some 20th-century composers added more letters (György Ligeti sometimes specified pppppppp!) But usually, notated dynamics only extend from ppp to fff. I’ve added the quadruple dynamics here just to cover the extremes.

Here’s how you might describe these levels in casual terms:

- pppp = nearly silent

- ppp = soft whisper

- pp = library voice

- p = restrained speaking voice

- mp and mf = between loud and soft. (Much like the weather forecast terms “partly sunny” and “partly cloudy,” these can be hard to differentiate.)

- f = strong speaking voice

- ff = shouting

- fff = screaming

- ffff = shrieking your damn head off

Can you play at ten different dynamic levels? Let’s find out!

Ex. 1 is a simple two-measure progression, played in steady eight-notes using downstrokes. I recorded using acoustic guitar because the instrument’s dynamic range is far greater than that of an amplified electric guitar. (More on that in a bit.)

Click here for Ex. 1

How Low Can You Go?

Before trying all ten levels in succession, search for the extremes your hands and instrument can produce. How close can you get to silence? What happens when you play so hard that you worry about damaging your guitar? (Composers generally use ffff for a deliberately brutal effect, so I interpret it as “the loudest racket you can make, even if it sounds crappy.”)

The specific notes in these examples don’t matter—use any strummed chord progression that you can stand to hear at least ten times. Try playing it ten times back to back, evolving from near-silence to brutality. It’s hard! But even if you fail miserably at first, you’ll still get something from this exercise. If you spend a few minutes focused on these small dynamic gradations and then move on to freestyle playing, I guarantee you’ll exercise greater dynamic sensitivity and variation. Try it!

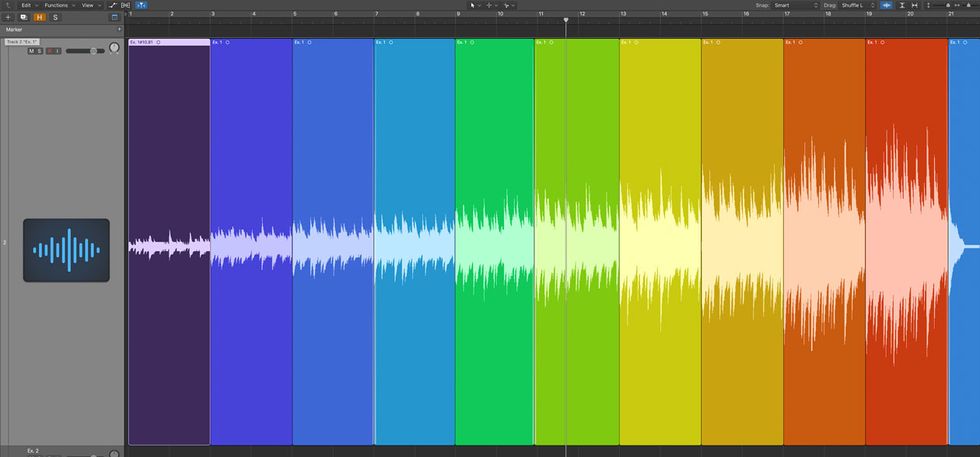

Ex. 2 is the same basic idea, but with single-note picking.

Click here for Ex. 2

Ex. 3 is similar, but this time with a two-measure fingerpicking pattern.

Click here for Ex. 3

Check out the waveform view of the Ex. 3 recording (Fig. 2). My performance is far from perfect—some transitions are too subtle, and others are too sudden. But the trumpet-like shape of the ten phrases side-by-side conveys the general idea.

The rhythm in Ex. 3 is more groove-oriented than the first two examples. That brings us to a major issue concerning dynamics and rhythm: It’s extremely difficult to maintain a steady groove at contrasting dynamic levels. First, it’s hard not to accelerate as you transition from soft to loud playing. Also, we probably alter our technique between levels. You might, for example, palm-mute at ppp, shift to a loose wrist at p, and use your entire forearm for ff. Is it even possible to maintain a consistent groove throughout?

Yes—and some musicians are really good at it. Example: Over the years I’ve worked a lot with drummer Bryan “Brain” Mantia (Primus, GN’R, Tom Waits). He’s an extremely loud player, yet his dynamic control is phenomenal. One time he was playing a heavy groove during a session, and the producer came in to discuss something. With absolutely no change in feel, he transitioned from an aggressive fff to a ppp quiet enough to speak over. It felt like a perfectly smooth logarithmic curve, as if someone had turned down the volume knob on a radio. Then he carried on a technical conversation while holding down a rock-solid groove at whisper volume. I can’t quite do that, but at least I know it’s possible.

Try this acid test: Take any short musical phrase and try alternating between ppp and fff after each repetition. Can you maintain a consistent groove? (Don’t freak out if you can’t. It’s hard!)

Electric Guitar Dynamics

Some instruments, like violin and piano, have huge dynamic ranges. Some, like harpsichord and old-school synthesizers, have none. Electric guitar falls between those extremes. It certainly has a narrower dynamic range than acoustic guitar. (I refer only to volume changes you create via playing pressure—not what happens when you twist the amp’s gain knob.)

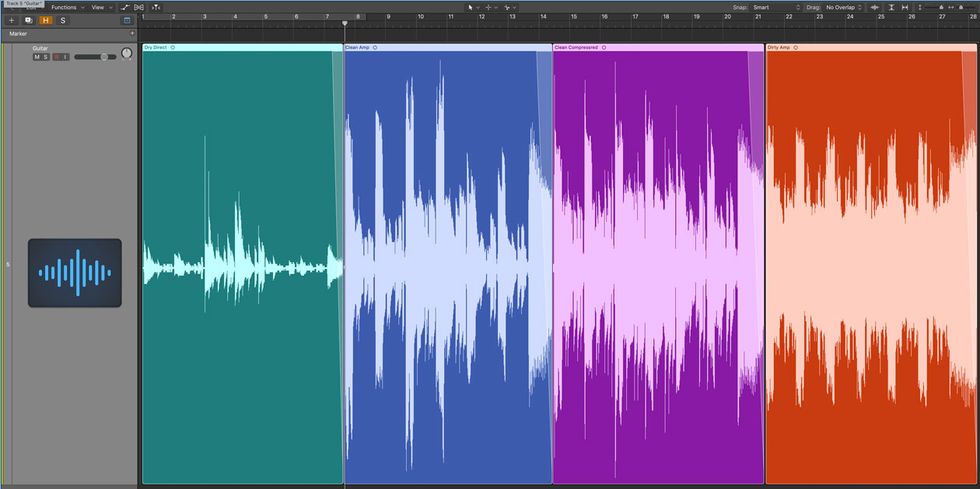

Partly that’s because the stages in an electric guitar tone chain compress the signal, which means less dynamic range. You can hear the process in Ex. 4. (The clip sounds super nasty, but it’s illustrative.)

I recorded a short riff directly through a clean preamp straight into Logic Pro—you hear that first. Then I reamped the performance through a semi-dirty amp. Next comes the same sound, but with a compressor plug-in added at a typical electric guitar mix setting. Finally, you hear the same riff through a heavily distorted amp. See the consequences in Fig. 3.

In the rinky-dink dry recording, there’s much distance between the loudest and quietest notes. The first amp tone isn’t just louder overall—there’s less distance between the loudest peaks and quietest valleys. Adding a compressor for the third repetition increases this effect. Finally, you hear a high-gain amp, which compresses even more.

This compression is generally desirable, adding sustain and body to your tone. In fact, some players deliberately limit their dynamic range. That’s essential for shred playing, where the focus is blinding bursts of identically articulated notes at unvarying levels. That happens to be one reason I don’t relate much to shred playing, but that’s just personal taste. We’d never say a pearl necklace is ugly because its pearls are perfectly matched. There’s no “correct” answer here.

Fortunately, electric guitarists have tools to increase dynamic range, such as gain pedals and multi-channel amps. But while you’re unlikely to match an acoustic guitar’s dynamic range, it’s still worth trying these exercises on electric. At the very least, they’ll challenge your ears and hands in new ways—and that’s always a good thing.