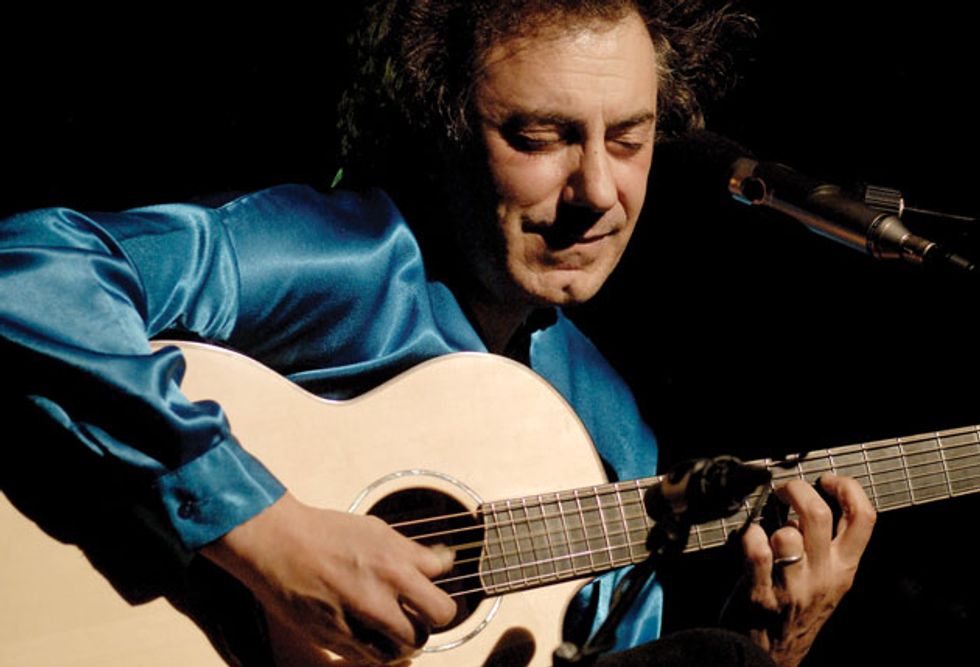

As anyone who has heard Pierre Bensusan live can attest, the French guitarist is among the world’s finest solo performers. Difficult to pin down to a single style, Bensusan has played steel-string fingerstyle guitar with peerless compositional depth, harmonic richness, and dynamic range for 40 years. “Pierre’s work transcends the guitar itself,” says fellow fingerstyle god Tony McManus. “What he communicates are pure musical ideas—storytelling in melody, rhythm, and harmony, always creative and always inspiring.”

Bensusan started out playing folk guitar and bluegrass, which eventually led to a gig as mandolinist for American banjo master Bill Keith. But the release of Bensusan’s debut album Près de Paris in 1974 (at the age of 17!) immediately established him as an extraordinary guitar talent. In the years since Bensusan has released nine more albums (not counting compilations and box sets). While his early efforts focused on arrangements of traditional Celtic music, the emphasis has increasingly shifted toward original compositions influenced as much by jazz and classical music as by North African styles, showing Bensusan’s Algerian heritage.

Most Bensusan recordings feature additional instrumentation (2000’s Intuite is his only true solo studio album), at times veering into a smooth new age/adult contemporary sound, though always featuring stunning guitar work and gorgeous, engaging compositions. But many fans have longed for an album that captures Bensusan as he appears onstage: solo, with his guitar tuned to DADGAD, the tuning he’s used almost exclusively since 1978.

Good things come to those who wait. Not only has Bensusan released a live recording, he decided to make it a beautifully packaged three-CD retrospective. “I wanted to celebrate 40 years of making a living with just my own work, making very little compromise,” he said via Skype from his home near Paris. “My life is on the road. I exist mostly because of my concerts.”

The result, fittingly called Encore, is a stunning overview of Bensusan’s career. While not arranged chronologically, Encore features glimpses into Bensusan’s earliest work playing bluegrass with Keith and solo guitar arrangements of tunes originally found on Près de Paris.Also featured are incredible versions of such tunes as “Nice Feeling,” the Middle Eastern-flavored tapping masterpiece “Agadiramadan,” and "So Long Michael,” Bensusan’s beautiful tribute to Michael Hedges, as well as the looping and vocal workout “Cordillière.” There are also several previously unreleased staples of Bensusan’s shows, such as the guitar and scat-singing “Bamboul’hiver,” and even a couple of duets with Dream Theater keyboardist Jordan Rudess. Overall, Encore is an amazing 40-year retrospective that sounds great (thanks to Grammy-winning engineer Rich Breen) and serves as an excellent introduction to Bensusan’s work.

What was it like to listen to recordings of yourself from 30 or 40 years ago?

It was agonizing! I hadn’t heard most of the recordings in years, and you never know what you’re going to find. I spent three months without playing, just listening.

How did you decide what to include?

It had to do something to me. It had to move me. The guitar had to be in tune, and the sound had to be decent. Even if the sound wasn’t decent, I’d choose the performance over the sound. For instance, the Celtic medley was recorded in Charlottesville, and every time I played my second bass [5th] string, there was a bit of feedback. That dictated my way of playing, because I tried not to hit that string too much, and when I did, I tried to control the resonance and sustain so it wouldn’t be overwhelming. I thought, “Okay, that’s bad luck, but the playing is really fine.” It’s a marathon—for 18 minutes!

I’m glad you included some early bluegrass recordings. Not many players have gone from flatpicked guitar and mandolin to fingerstyle. Were you already doing both at the time?

I was doing guitar first. I enjoyed bluegrass music a lot and played with a flatpick. Then I joined a band in a suburb of Paris, and we couldn’t find a mandolin player. My friends asked me to play the mandolin, so I bought one the next day. My reference and inspiration came from people like John Duffey, Sam Bush, Bill Keith, and the Stanley Brothers. I also loved Country Cooking, and Clarence White with the Kentucky Colonels. I was going to some hidden record stores in Paris where you could find those records. The guy working in one of those stores came to me one day when I was 16 and had just left school. He said, “Would you like to join the Bill Keith Bluegrass Band? I’m going to produce a tour for him.” I said, “You’ve got to be joking!” That’s how it started for me. Those recordings come from that very first tour.

I took my guitar with me on the road because I was backing Bill on one song, using a flatpick. In the daytime I would practice on my own, and Bill heard me play those different arrangements of Celtic tunes and some of my own compositions. He said, “I want you to play a couple of numbers onstage every night.” That’s how it started for me, because we were in Belgium, France, and Switzerland, and all the promoters of those shows wanted to invite me the next year on my own.

You mostly play original music now. Do you have a composition process?

Probably, but I’m not aware of it. I listen to the music inside of me. As Bobby McFerrin put it, I am my own Walkman. The idea is for the moments when I play and the moments when I hear music to coincide, so that I can play what I hear. There are a lot of different approaches for getting there on the guitar. One of them, of course, is to be ready technically. I never feel that I’m ready, but I work a lot on my arrangements and my technique. I want something difficult to become agreeable and pleasant so I don’t have to be anxious when I play.

Your live shows have the feeling of a single connected event, rather than a bunch of tunes strung together. How much do you plan your set, and how much just happens?

It’s both. I feel that a show is a bit like listening to a record or reading a book. You can’t do just anything at a show. I wish sometimes that I could start a show on a very high energetic point. I get there during soundcheck, but when the show comes, I need to calm down, start low, and then come up and up until the end. I try to give a form to the concert so that it sustains attention until the end. It has to include contrast, surprises, predictable moments, and unpredictable moments.

You’ve said the tuning players use doesn’t matter much as long as they’re familiar with it. But obviously, DADGAD had a big impact on what you do.

It’s not a tuning that influences me—it’s the music, and DADGAD becomes a tool. But at the beginning, DADGAD was amazingly and vividly present, and it probably shaped my approach to the guitar for a while. But I realized very soon that you had to look for the notes, and it was not obvious. A lot of people take open tunings for granted. They get a flattering first impression, which is great, because it inspires. But you can’t stay there. That’s why I chose to play in only one open tuning, rather than spend my time going between various tunings and always having challenges with intonation, breaking strings, and never really knowing my way. I chose DADGAD in 1978, and my life became much simpler.

Pierre Bensusan Gear

Guitars

Lowden Pierre Bensusan Signature Model

1978 Lowden S22

Amps and Effects

Highlander iP-1 pickups

Line 6 Relay G30 wireless system

Ernie Ball volume pedal

Roland RC-50 Loop Station

Universal Audio Apollo Duo FireWire audio interface

MacBook Pro

Schoeps CMC 64 mic for guitar

Neumann KMS 104 mic for vocals

Strings and Picks

Wyres Signature DADGAD set, gauged .013, .017, .023, .032, .042, .056.

How did your collaboration with Jordan Rudess come about?

We met at the New Milford summer camp in Connecticut 20 years ago and became friends on the spot. A couple of years later I was commissioned to create a piece for a children’s choir. I invited Jordan to join me. We were the only two musicians backing 200 singers! In the first part of the show, I played solo a bit and then I invited Jordan. We played some duets, and two of them can be heard on Encore. That was the only time they were played, so I was very pleased that they were played so well.

You played your original Lowden S22 (“Old Lady”) exclusively for 25 years, and now you’ve been playing your signature Lowden for quite a while. Can you compare those guitars?

I played the Old Lady in Germany the other day, because my signature Lowden was stuck between airplanes. It was not even set up, so I found a great German luthier, Dietmar Heubner, who spent three hours setting it up for the show. I played the guitar all day to get familiar with it again, and I felt, “Oh my god, this is my home!” It was amazing to play that guitar again. It was like, “Why do I play another guitar?”

Two Extraordinary Lowdens

Pierre Bensusan is a virtual guitar monogamist. Sure, he played a Gurian at the very beginning of his career, and for a few years he played a signature model Kevin Ryan guitar. But for most of his career, he’s been a Lowden man.

Bensusan first fell in love with Northern Irish luthier George Lowden’s work in 1978, when he acquired an S22 (equivalent to today’s O-22 model). Featuring a cedar top and mahogany back and sides, the guitar was originally a non-cutaway model. Rather than replace it with a new guitar when he felt that a cutaway was necessary, Bensusan had Lowden modify it in 1989, and also had the fretboard and string spacing widened. For 25 years “Old Lady” was the only guitar Bensusan played. He still pulls it out of semi-retirement from time to time.

In 2009, Lowden and Bensusan began work on a signature model. To the surprise of some fans, the result wasn’t a copy of Old Lady, but an updated guitar. Using the company’s midsize F-model body, the guitar is built with an Adirondack spruce top and Honduras rosewood back and sides. It also has a bevel on the bass side of the lower bout, a maple neck with a nut-width of 1.77", and fairly wide string spacing of 2.36" at the saddle. An unusual but very cool feature is the neck shape, available on other Lowdens as a “fingerstyle” option: It flares out slightly more than standard, providing a bit more width in the upper positions, which makes it less likely to slip off the fretboard when playing vibrato on the outside strings. The guitar’s list price is $8,765.

Bensusan and Lowden are now working on a 40th-anniversary signature model: a faithful recreation of Old Lady. Due in 2014, the guitar will have Lowden’s original jumbo body (slightly deeper than the current O-shape, and with a more pronounced taper between the neck block and the neck joint), older-style parabolic bracing, and an optional bevel.

How does it differ from your signature model?

It’s richer. You can’t invent 35 years of life in a guitar. Even if today the high harmonics have less sustain, they are still very present. In fact, I like less sustain, because sometimes it’s overwhelming, and it’s hard work to tailor that sustain so that it’s not in the way of the musical conversation. But the new guitar is a very special instrument. It’s three-dimensional. It has depth, horizontality, sustain, a lot of harmonics, and a lot of sound. The relationship between a note and the history of the note is extremely vivid on those two guitars. It’s a bit like the taste of a great wine. There’s the first taste, and then the whole history of the taste after the first drop. Both guitars have that quality, which is what defines a great instrument.

What can you tell us about your amplification setup?

First of all, the pickup is very important. I use the Highlander. From there I go into a Line 6 wireless preamp, an Ernie Ball volume pedal, and a Roland RC-50 looper. From there it goes into Universal Audio Apollo Duo hardware, and then into a MacBook Pro. I’m very happy with that setup. I can now do my stage monitor sound on my own. I can even do my front-of-house!

And your guitar and vocal mics also go through the MacBook Pro?

Yes, and all the effects—reverb, limiter, expansion, EQ—are there. I can even record the show.

Why a volume pedal?

It’s very convenient, because when I tune, I cut the sound. I also use it to shape the note attack for a bowing effect.

What are you using an iPad for onstage?

For walk-in music. I also use it for my song lyrics, and I have a little Bluetooth foot controller that turns the pages.

What’s next?

I’m going to be doing a lot of touring from January until the end of July. Until then, I’ll stay home, work on some new pieces, revise my old pieces, work on my improvisation, and catch my breath a bit. I’m doing my album release shows in Paris, and I’ll be in the States from March until May. It’s going to be a driving tour with my new van!

YouTube It

If you haven’t heard Bensusan, you’re in luck—there are lots of great clips on YouTube.

A mid-1980s performance of “Nice Feeling.” (The title is a play on the word “nice” and the French city of Nice.) This performance occurred before Bensusan’s Lowden S22 (“Old Lady”) was modified with a cutaway and wider, extended fingerboard.

Pierre Bensusan plays “Agadiramadan” on Old Lady in 1993. Note the fluid single-note improvisation over the looped theme.

Pierre Bensusan plays his tribute to the late Michael Hedges, “So Long Michael,” on his Lowden Signature Model.