“The guitar is the easiest instrument to play and the hardest to play well.” —Andrés Segovia

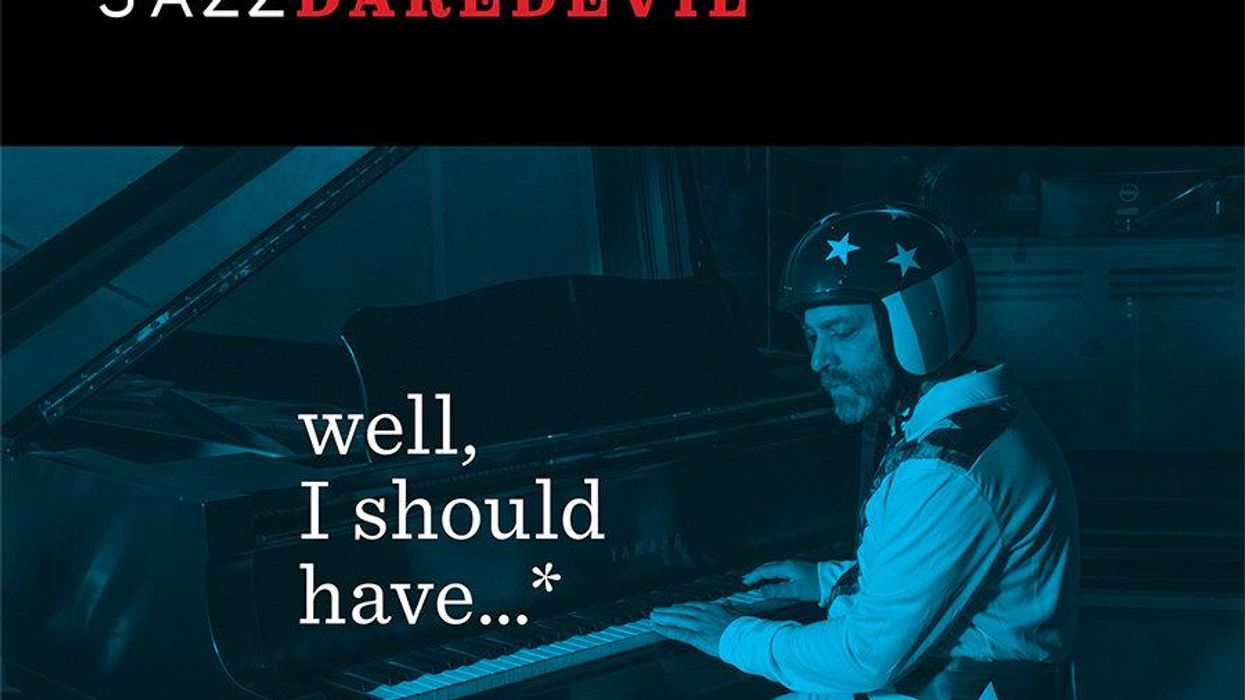

You probably know H. Jon Benjamin’s voice. He’s the voice actor for Archer in the animated sitcom Archer, as well as Bob in Bob’s Burgers, and Carl in Family Guy. (Okay, so I watch a lot of cartoons). In 2015, Benjamin recorded a jazz album, Well, I Should Have…, with some true jazzers—Scott Kreitzer on sax, David Finck on bass, Jonathan Peretz on drums—and Benjamin on piano. Here’s the twist: Benjamin does not play piano. Nor is he a fan of jazz. He just went for it, and Sub Pop released it.

Admittedly, I couldn’t make it through the entire album, but I did enjoy a two-song serving. Most of the time, Benjamin sounds like a not particularly gifted 13-month-old child in a room with a piano and little else to entertain him. His timing is … well … time-less: a bit like tennis shoes in a dryer. His note choice is arbitrary, there’s no sense of melody or dynamics, but every now and then, he plays something that sounds like music, usually when he gave it some space. Regardless, the band was swinging, so his pocketless nonsense sometimes kind-of worked. Honestly, I’ve been lost at a gig or a session and sounded about as musical as Benjamin until I recovered. As you might imagine, the album angered a lot of jazzers (who kind of seem a little angry anyway), but if the point of jazz is to push boundaries and transcend norms in a spirit of true artistic experimentation—mission accomplished.

Who hasn’t listened to jazz and wondered, “Did they mean to do that?” Throughout Thelonious Monk’s entire career, there were people who saw him, heard him, and even hired him, who thought Monk didn’t know how to play piano; as if his entire career was a ruse, a deep fake. With his fingers splayed out and attacking the keys in this unorthodox method, all that dissonance and weirdness combined with mental illness made Monk’s music a bit difficult to digest. But that’s art: genius working on the border of the frontier of new ideas is rarely recognized.

“As you might imagine, the album angered a lot of jazzers (who often seem a little angry anyway), but if the point of jazz is to push boundaries and transcend norms in a spirit of true artistic experimentation, mission accomplished.”

On the other hand, you don’t have to know what you’re doing to make good, or even great music. Even a cat walking across a piano can play something cool, or creepy, and almost always engaging. Even when a musician really knows what they’re doing, there are often bits of music that go beyond what the player is capable of crafting intentionally. That’s part of music’s magic—play long enough, and your fingers will unconsciously stumble into a cool riff or melody. It may be dumb luck, or it may be that the player is channeling some benevolent spirit of music who sings through them.

For an example of channeling, check out Daniel Lanois. He’s produced and played on a handful of albums that are on Rolling Stone’s “500 Greatest Albums of all Time” list. When I watch Lanois play guitar or pedal steel, I get the feeling he has no idea where he’s going, or what he’s playing. It feels like he’s connected to something spiritual, and the result is something between a prayer and a howl.

That’s why those Lanois albums hold up so well. If a hired-gun guitar virtuoso played those sessions, those parts probably wouldn’t have said as much. Most studio aces would play something they’ve played before. It would sound great, but probably wouldn’t be as effective as Lanois’ playing. If you know your instrument extremely well and work out a clever part, you run the risk of thinking your way out of the emotion. It happens to great players regularly, so maybe it’s hard to let the muse drive the ship when you’re a highly skilled captain. Kurt Cobain was not a technically gifted guitarist, but Nirvana’s body of work expressed something—angst, depression, alienation—that millions of people immediately related to, so much that Nevermind single-handedly changed popular music. At a time when popular music was “Nothin’ but a Good Time,” big, teased hair, guy-liner, and garish colors, Cobain didn’t shy away from dealing with negative emotions and the challenges of life. In fact, he embraced it and connected with the masses.

“But that’s art: Genius working on the border of the frontier of new ideas is rarely recognized.”

Music does not discriminate. It can be created by anybody: geniuses, idiots, children, or senile old people with one foot in the grave. There are no sure things. You can spend a lifetime dedicated to creating music, become a brilliant musician, and still occasionally sound like you have no idea what you’re doing. As blues great Coco Montoya told me during his Rig Rundown, “Sometimes you get Coco, sometimes you get caca.”