It was around 8 p.m. and, after enduring a severely delayed flight from Europe, Mike Stern had finally arrived home to New York City. He was overseas for a run of marathon three-and-a-half-hour shows in Munich and Budapest, where he shared the stage with fellow guitar virtuoso Al Di Meola on the Mandoki Soulmates’ A Memory of Our Future album release concert.

Even though Stern had to leave the next day for a week-long stint at the Alternative Guitar Summit camp—where he would do clinics and perform alongside giants of the modern jazz world including John Scofield and Kurt Rosenwinkel—he invited me over that night to his Gramercy Park apartment to discuss his debut Mack Avenue Records release, Echoes and Other Songs.

As I set up my recording equipment, Stern was also busy setting up. He opened his Boss BCB-60 pedalboard case and connected his pedals to his well-worn Yamaha SPX90II, then routed the setup into a pair of Fender Twin Reverb reissues. “I just want to set my stuff up so I can practice later,” explains Stern. He was very generous with his time, and our interview concluded around midnight. As I headed out, Stern was just beginning his hours-long, late-night shedding session.

This relentless drive and obsessive discipline are the keys to Stern’s “chops of doom,” his nearly half-century reign as one of the world’s most celebrated jazz-fusion guitarists, and his remarkable road to recovery from a horrific accident that happened eight years ago.

Mike Stern - "Echoes"

In the Aftermath

In the summer of 2016, Stern tripped and fell over improperly stowed construction equipment while crossing the street, and broke his humeri (both of the arm bones that extend from the shoulder to the elbow). His right hand suffered permanent nerve damage, which caused it to become bent like a claw, making it so that he can no longer do some things like fingerpick and pinch harmonics. Stern’s legendary fluid picking style also became choppy, and he’s had to work extremely hard over the years to get it to flow smoothly again. “It’s still frustrating as hell,” admits Stern. “You didn’t have to think about the technique so much because you’ve been doing it for years, and then all of a sudden, now you have to spend energy and brain power on it. But it’s getting more natural as I keep doing it.”

“You didn’t have to think about the technique so much because you’ve been doing it for years, and then all of a sudden, you have to spend energy and brain power on it.”

Equally devastating is the mental toll from the accident, which Stern is still coping with. “I was really nervous to do the record at all. I was trying to give myself every excuse to get out of it. I thought, ‘Oh my hands are gonna cramp up because I’ll be nervous.’ My hands cramp up because of this injury,” says Stern. “It’s more in my mind. But that’s what I’m going through sometimes because of this. It’s really serious. I’m the only guitar player in the world that’s using glue—wig glue—to hold a pick. Everybody says they can’t hear the difference [in my playing] but I really feel it.”

Despite his initial, anxiety-driven apprehension, Echoes and Other Songs might be Stern’s best studio album yet. “I thought all the solos sucked and I’d have to go back and do everything again,” confesses Stern. “Then I listened back and, first of all, I can’t change it because it was all recorded live with the band, and then I said, ‘Thank God I don’t need to.’”

Stern’s new record features a slate of impressive collaborators, who gathered to cut the album in New York City.

Hitting with the Heavyweights

As typical for a Mike Stern record, Echoes and Other Songs features a star-studded lineup of musicians. The luxury of recording with some of the world’s best musicians comes at a price. “The problem was getting those guys to rehearse because everyone’s so busy,” says Stern. “We got one rehearsal with Jim [Beard, producer], myself, Antonio [Sanchez, drummer], and Chris Potter [saxophonist]. No Christian McBride [bassist]—so we ran the tunes without bass,” says Stern. “We finally got Christian to do it the very night before. He had some time and drove all the way in [from New Jersey], and there was a ton of traffic because there was a baseball game or something, and he was late, but he still made it. We got together for like an hour-and-a-half that night and went over everything. He already had it together.”

The next day at BerkleeNYC’s Power Station Studios, they recorded straight through without listening back. It was mostly one to three takes of a tune—maybe four at most, if something was tricky. Stern explains, “We didn’t have that much time—we only had two days to do eight tunes! That’s kind of a lot, especially because it’s very live and we had never played together.”

“I’m the only guitar player in the world that’s using glue—wig glue—to hold a pick.”

Stern did two days with that rhythm section, and the second session had Beard, Richard Bona on bass and vocals, Dennis Chambers on drums, and Bob Franceschini on sax. This was also intended to be a two-day session, but they finished the three tunes in one day, and were wise enough to leave it alone. (Later overdubs included Mike’s wife, Leni, on ngoni, a West African stringed instrument, and Arto Tunçboyacıyan on percussion.)

Over the years, Stern had worked with all of the musicians on the album, with the exception of Sanchez, who entered the picture at Beard’s suggestion. He had just played a session with Sanchez, and Stern recalls, “Jim said, ‘Wow, that cat is playing his ass off.’ I was like, ‘No shit, of course.’ I’m aware of him but we never played. Beard said, ‘It would be a really good hookup because Antonio’s such a great jazz player; he really follows you.’ And he did exactly that, he really followed me, especially on the first tune ‘Connections.’ All of it. He was right there for all the soloists.”

Mike Stern's Gear

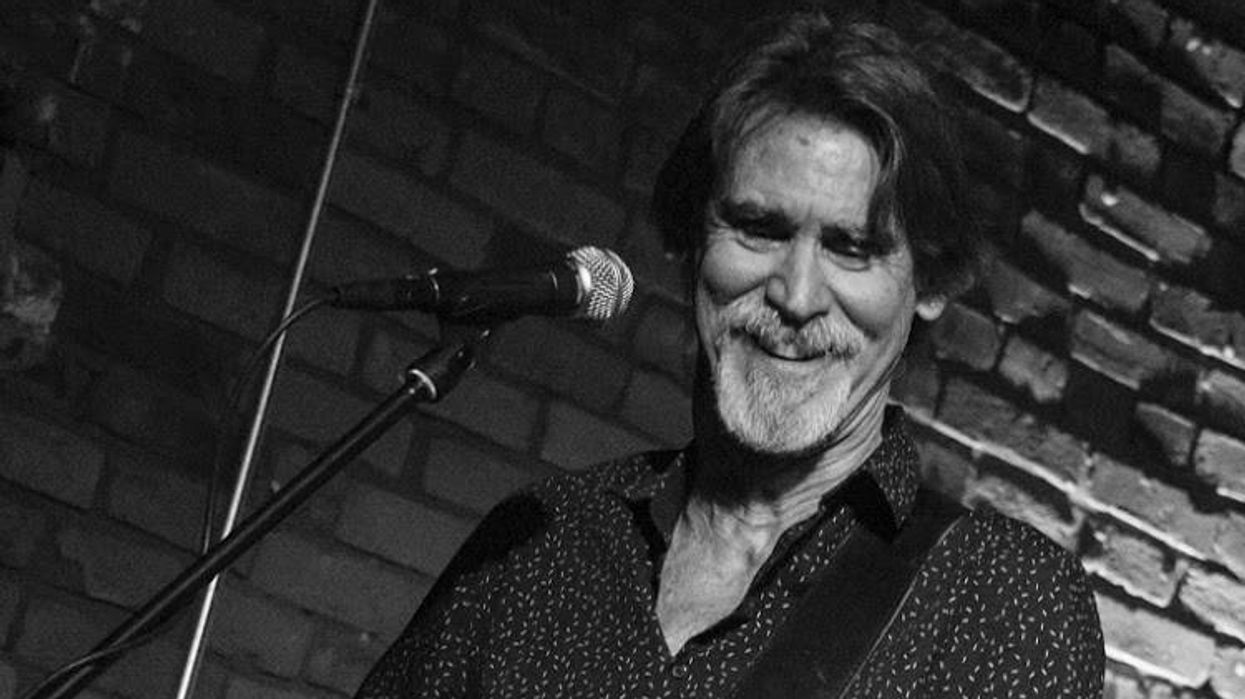

Improvising isn’t just for the fretboard: A 2016 accident permanently damaged Stern’s right hand, forcing him to relearn how to play the instrument—a process that’s still ongoing.

Photo by Sandrine Lee

Guitar

- Yamaha Pacifica 1511MS Mike Stern

Amp

- Fender ’65 Twin Reverb reissue

Effects

- Yamaha SPX90II

- Boss SD-1 (as boost with level all the way up, drive all the way off, and tone at 11:00)

- Boss SD-1W (as drive with level at 11:00, drive at 1:00, tone at 2:00, and mode switch set to C)

- Boss DD-3T

- Boss MO-2

- Boss TU-3

- Vemuram Jan Ray

- Truetone power supply with daisy chain cables

- Boss BCB-60 pedalboard

Strings and Picks

- D’Addario (.011–.013–.015–.026–.032–.038)

- D’Addario heavy picks

Beauty in Simplicity

Like most accomplished jazz musicians, Stern has spent countless hours shedding complex tunes. He’ll regularly practice John Coltrane’s “26-2” with Leni at home, and has recorded Coltrane’s challenging “Moment’s Notice” on several jazz-oriented CDs. But unless Stern is specifically recording an acoustic-jazz album like his 1992 release, Standards (and Other Songs), he generally prefers to keep it simple for his studio albums.

“I like to write so you don’t have to have a slide ruler to figure it out. That’s just my take,” says Stern. “I mean, some of the stuff that I hear that’s more complex, it’s gorgeous. I’m not taking that away. But when you have a limited amount of time for a band, you have to kind of keep it realistic. You have to make it kind of simple because most of the time they’re not going to have time to really learn some hard shit. I like to do that anyway because it’s more fun for me and for everybody else to play. It’s not so fun to show up and have to play ‘Giant Steps’ backwards and in three different keys.”

“I like to write so you don’t have to have a slide ruler to figure it out.”

You’ll often hear common forms like blues and minor blues disguised with the Stern touch on his albums. “Could Be,” the closing track on Echoes and Other Songs, is a quirky contrafact on the very familiar jazz standard “It Could Happen to You.”

“Connections,” another song in the collection, “has a blowing section that’s easy so people can take off on it,” says Stern. “It’s almost got a McCoy Tyner vibe; I always think of ‘Passion Dance’ in a way.” Since “Connections” didn’t require extraneous brain power to calculate unexpected chord changes or odd meters, the musicians were a lot freer and more relaxed, and the results are astounding. Stern says, “Man, Chris Potter, whew—he just tore it up on that track.”

Stern’s signature Yamaha electric has been his go-to for decades. Combined with a pair of Twin Reverbs, it takes him wherever he needs to go.

Photo by Chris Marroquin

“Gospel Song,” the second single from Echoes, is a ballad inspired by the down-to-earth music Stern heard growing up in Washington, D.C. “All you heard there was soul music, basically. It was so cool to live there and hear that music and it got me right away,” says Stern. “I used to listen to a lot of Motown and some church-y kind of stuff is in Motown or soul music.”

“Curtis,” which features Bona singing and Stern making an appearance on backing vocals, pays homage to a soul-music legend. “It’s got the vibe of a Curtis Mayfield tune in a kind of loose way. He’s one of my favorite composers,” says Stern. “You didn’t have to think too hard. It would just get into your heart.”

Fitting Farewell

Sadly, producer Jim Beard passed away in March 2024, several months before the album’s release. In addition to working with the likes of Steely Dan and Pat Metheny, among others, Beard had played an enormous role in Stern’s studio albums over the past several decades. “He played on ‘Chromazone,’” recalls Stern, referencing his most famous tune from the 1988 album Time in Place. Beard also produced numerous Stern albums, starting with 1991’s Odds or Evens. “He produced and mixed the stuff too, even though we had engineers. He’s amazing and had such an incredible ear. It was a shock to lose him,” says Stern.

Fittingly, “Crumbles,” Stern’s most adventurous studio track to date, features Beard, who adds a hauntingly introspective touch to the song’s mood. “The tune is a little quirky and has some humor in it. I like some of the things I was trying to do writing-wise and Christian really dug it. We were in the studio and we said, ‘Everybody’s been playing here and there but Jim hasn’t really gotten any features, so let’s just do that with him.’ He played this spacey thing and everybody just kind of played along, but we kind of knew we were going to go back in time and rock out in the end,” says Stern, who pulled out his synth-like Boss MO-2 for the guitar solo. “It just happened. I hadn’t used it for the whole record, so I said, ‘Let me use this with distortion.’”

Stern and his wife, musician Leni Stern, have always practiced as a duo at home, but they only started performing together recently. In this live shot, Leni presides in the background.

Photo by Chris Marroquin

The 55 Bar

Since roughly 1984, NYC’s 55 Bar was Stern’s home away from home. He had a weekly residency there for decades, playing every Monday and Wednesday when he was back in town. In stark contrast to a formal concert at a big-money venue, gigs at the 55 Bar—lovingly nicknamed “The Dump”—were casual, low-key situations. For guitar geeks, it was the best deal around, especially in the early days when the $12 cover charge also included two drinks and popcorn.

At his 55 Bar gigs, Stern would tweak new compositions and arrangements, and stretch out on jazz standards. It wouldn’t be uncommon at the 55 Bar to hear Stern burn for 20 minutes on a very uptempo blues, exploring esoteric ideas that you might not hear him do on a more listener-friendly studio album. Or, he could morph a jazz standard into an endlessly building, extended-outro vamp where he would play ear-twisting lines.

“Playing [at 55 Bar], sometimes I would come back that night and be inspired to try to write something.”

Musicians as diverse as Hiromi Uehara, Paul Shaffer, and the late Roy Hargrove would often randomly show up and sit in with Stern. Countless magic moments happened at the 55 Bar, very often sparking new ideas for Stern. “Playing there, sometimes I would come back that night and be inspired to try to write something,” says Stern, who made his first public appearance after the accident at 55 Bar on October 10, 2016, and used subsequent gigs there as a rehab of sorts as he began relearning the instrument.

At the club, Stern created a culture that defined a New York movement in jazz guitar, and gave players like Wayne Krantz and Adam Rogers, among others, an opportunity to showcase their abilities and develop their craft.

Sadly, however, in 2022, the 55 Bar closed, striking a devastating blow to the Big Apple’s creative community. “That place was one in a million,” says Stern.

“It’s a total drag,” he continues. “You have to look around and hustle gigs. It’s a challenge for younger players to find clubs to play and keep going. Even as discouraging as it is, I tell people, whatever you do, just try to find time to practice. Find a couple of hours every day. It’s a corny phrase but just ‘water the flowers.’ Otherwise, you got nothing.”

YouTube It

After decades of gigging separately, Mike Stern and his wife Leni Stern decided to start performing together. Leni’s ngoni playing can be heard on Echoes and Other Songs, and in this clip, the duo jam at home on one of Leni’s West African-inspired songs.