On July 3, 2016, Mike Stern was headed to Europe to kick off a tour. He never made it. Hours before his flight, he tripped over hidden construction debris in the street. “Once I lost my balance, I thought, 'Uh oh, it looks like I'm going to fall.' Then I was trying to regain my balance—my feet were moving faster to catch myself. But I didn't," recalls Stern. “I fell on my elbows or forearms, but the shock is felt from the humerus bones, and it goes right up to the shoulder. I broke both of my humerus bones."

As bad as it sounds, that wasn't the worst part. The accident led to nerve damage in Stern's right hand—the secret weapon for his jaw-dropping, alternate-picking technique. This discovery was incredibly traumatic for Stern, who is notoriously obsessive about the guitar. For decades, he's had the instrument in his hands for practically every waking moment.

“Mike spends eight hours on the guitar every day that he's not travelling," explains his wife, renowned guitarist/multi-instrumentalist/singer Leni Stern. “That's how he plays like he does." A typical day saw Mike waking up early to practice for several hours, then he'd practice with Leni, and then a bassist would come over and they would play for a few more hours.

Leni reveals, “When I practice my other instruments—n'goni, calabash, and voice—the bass player comes to replace me in Mike's practice room." To top this off, he'd do a three-hour gig in the evening. Having lived with this daily routine for decades, not being able to even hold the guitar was incredibly disheartening for Stern. But he refused to give up hope.

With his right hand still badly mangled and bent like a claw, on October 10, 2016, Stern made his return to the 55 Bar in New York, where he maintains a Monday and Wednesday residency whenever he's not on the road. To be able to hold the pick, he wore a glove to which picks were taped. About two weeks after that, he played a series of shows at the Blue Note with Chick Corea's band, which featured a formidable lineup including saxophone titan Kenny Garrett.

Stern has since had several surgeries to maneuver his thumb to be able to actually hold the pick. Still, even with all these obstacles to overcome, between January and March 2017, he recorded Trip, his appropriately titled 17th album as a leader. The album features Stern's signature brand of intricate funk-bop on tracks like “Whatchacallit" and “Trip," tender ballads like “I Believe You" and “Gone," and recrafted jazz standards like “Scotch Tape and Glue," based on “Green Dolphin Street," and “Half Crazy," based on “Rhythm Changes."

Premier Guitar caught up with Stern at his NYC apartment to discuss the making of Trip, the recovery process, and how spirit is everything.

Tell us exactly what happened with your recent accident.

It was a very unlucky day. They'd left some kind of construction stuff that was invisible right on the median of the road. It was yellow on yellow—usually they have, like, bowling pins sticking out to divide traffic—and there were none. So, I was just walking normally and tripped on that thing.

I fell kind of like a quarterback falls sometimes. This is a common quarterback injury, when you have your arms up, protecting your face and your head. I thought I dislocated my shoulders but they told me I broke my humerus bones. The left one was a clean break but the right one was really messed up—it was broken in four places, but still they let me out the same night.

I understand you also ended up getting nerve damage.

Apparently, this is a very rare symptom. It doesn't happen very often that you get nerve damage in your right hand from a break all the way up here. At first they gave me a doctor that was in-house at New York University hospital. He was a specialist but a general specialist. Now, I've got this other doctor—Alton Barron—that Wayne Krantz recommended. He's really one of the top guys in the world. He's a guitar player, too, and he's worked with musicians and sports guys forever. Last time I was there, this guy showed up and gave me his number [points to concert pianist Lang Lang's name scribbled on his wall Rolodex]. So that's the place.

What was his diagnosis?

Three weeks after the accident, I had all this metal in my shoulders but my hands weren't really coming back. They were still numb, and the other doctor was telling me it should happen, or it might take time. Everybody was telling me that. The new doctor recognized right away, and said, “I've never seen this much numbness three weeks after an accident." He knew that I'd be out for a long time if he didn't do something, and he did something so I could hold a pick. And recently he did something else so my thumb would be better.

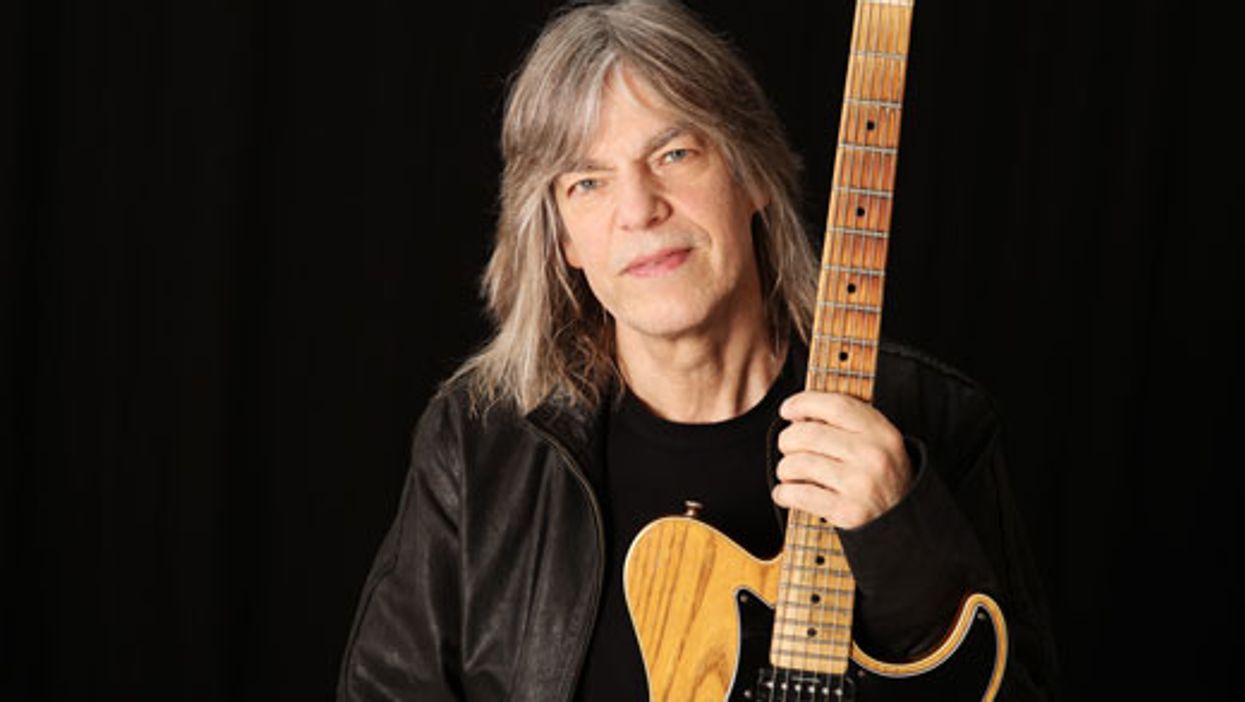

Mike Stern's album Trip is his first release since suffering serious injuries to his arms and hands when he tripped over roadside construction debris in 2016.

Are these temporary fixes just to get you playing for now?

It's just in case. If something else heals, then you don't have to worry about it. You have extra tendons in your hands that are just sitting there not doing anything. If you get the right guy, you can really do a lot. But I think his feeling at the time, and he wasn't sure but now it looks like it's correct, is that I'd go crazy if I couldn't play for a whole year—he was right. Two months later, I was playing.

That must have been a tough time for you, mentally.

Spirit is everything, no matter what goes on with you, if you get low and feel depressed. Ray LeVier [drummer] was a big inspiration. He was badly burned when he was a kid and has almost no hands, and he plays his ass off. When this happened, someone said, “Call Ray," because I was using a compression glove, Velcro, and tape. Ray said, “Try wig glue." Like Donald Trump uses [laughs]. So, I tried, and it worked a lot better.

That was last October [2016]. Since around March, the doctor also did something with my thumb, so now, generally, everything's better. But I did Trip before that. I had a lower primate thumb, kind of like a monkey's thumb, for a minute, and I had to do the record like that.

I remember your first gig back at the 55 Bar, and your attack was a bit choppy. On Trip none of that is present. How were you able to control that?

When you're recording, you're sitting down and you can do a couple of takes. When it's live, if you drop your pick, then it's over. It's not like you can go “take two," because the pick is sliding. The recording was a little easier in that regard, but it also came out a lot better than I thought. I'd go back into the control room and say, “That feels like shit," and then I listened back and went, “Wow, that's a lot more happening than I thought." So, I was able to get through it pretty good, and I was happy with how it all came out. You know the choppiness? That's not a bad thing necessarily, if it's in the groove, and if you get your ideas out. And there was always a little because I pick every note.

Did you do a lot of takes?

I had to fix a little bit, but as little as possible. I like to do everything live and get a good take. It was more just sitting down and not feeling like this is the only take I could do. That makes you relax a little more. I like to keep my live stuff, mistakes and all.

Did you overdub parts or do complete passes?

I did complete passes.

Not just phrase by phrase?

Oh, no way. I don't know how to fuckin' do that. I used to do a little bit of that way back in the day, or if something bad happened with the sound. But for years, I'd just go for the basic solo, and if there's anything that I want to fix later, I'll fix it, but as little as possible. I mean, there's no other way to capture the interaction that happens, especially with drums, the rhythm section, and the soloist. Unless you're doing something where it's really freeze-dried, like where the drums just play a part or it's not so interactive. Then it doesn't matter. But I like a lot of interaction, even on a ballad.

There are some spots on the album, like the solo in “Screws," or at the outro of “Trip," where you go nuts and play super fast and aggressively. Even moreso than you have on recent albums. Did you feel like you had to prove to yourself that you could still do it?

Maybe a little. I think also some of the tunes I'd written have some of that kind of energy. I like to play for the tune. Like if it's a song like “Gone," the acoustic guitar piece where it's a lot slower and more lyrical.

“I like a lot of interaction, even on a ballad," says Stern, who has played with the best of the best, including Miles Davis, Jaco Pastorius, Chick Corea, and Eric Johnson. Photo by Jordi Vidal

At a recent 55 Bar gig, you told me you've played some things that you were surprised you could do, and you even wondered if you could've done them before the injury. What types of things were you referring to?

Sometimes it's hard to tell. That's one of the tricky things. If you're self-critical, like we all are, you listen to yourself on tape and go, “Aw man." You're your own worst critic. You're usually harder on yourself than anybody else and it's hard to objectively sit back and criticize. And some nights you think something's great and you listen back and it sucks. You never know when you're doing it. One of the hardest things for me to do is to figure out what I used to be able to do, and what I can do now, and what the difference is. That's part of the mind mess you can get into. Your brain says, “I used to be able to do that and now I can't do it anymore." And then you start thinking, “Did I used to be able to do that?" Because that was a hard thing to do in the first place.

How do you now play things that must be fingerpicked, like the open-voiced triads you often do on ballads?

That's kind of a battle. But open triads aren't a problem [demonstrates by playing open-voiced triads pick-style and using the fretting hand fingers to mute the inner, open strings]. What the doctor is going to do, I think, is straighten these out a little [raises middle and ring fingers of picking hand]. See how my index finger is bent a little bit? He did that on purpose for the initial time, so I could do a pinch and hold the pick. At first, he had me try Velcro but it didn't work.

It looks like now you're using more arm motion for your picking, rather than wrist.

I've always done that a little bit. I still do the wrist movement, and that's happening more because I can hold the pick better.

Can you still do that signature tremolo-picked, chord thing with the arm motion?

[Plays tremolo-picked chords along with some fast runs.] It's close enough for me. I'm of the mind that even if it's a little funky, as long as you get your heart and soul out there, that's what music's all about. There are times when I'm doing someone else's record date, and a mix isn't great, and you don't have control over it. But I go for the soul. If it's within a ballpark, I'm cool with it. I remember when I did “Fat Time" [Stern's first recorded track with Miles Davis, who named the tune after Stern because he was heavy at the time and Davis liked his timing feel], there was clackiness and it was raw. I wanted to fix it here and there, and Miles Davis said to me, “Fat Time, when you're at a party you gotta know when to leave."

kick my ass."

I think John McLaughlin is fighting arthritis, but he's still playing his fucking ass off. Jeff Clayton [saxophonist and flautist] from the Clayton Brothers has Bell's palsy and can't close his mouth completely. He has to wear a special kind of strap to keep the air from coming out. I saw him on a jazz cruise I did, and he came into this rehearsal place I was at and started explaining what he's going through and he said one of the things that tends to happen is that you try to play it safe, but he said, “You can't do that. You gotta go for all of your ideas." And he plays his ass off.

Steve Morse has arthritis as well, and mentioned in an interview we did that, as a result, he's had to adjust his picking technique.

It happens but the cats that fuckin' deal, keep playing. There's so much you can do with music, including classical players. Julian Bream would drink a fifth of Jim Beam before he played a gig. One of the greatest guitarists and he was bombed.

It seems like you spend a lot of time writing, in addition to just playing.

I'm always writing. I probably have another record's worth of tunes. I was just up at Berklee doing a clinic and someone asked, “How do you get your own sound?" Basically, everybody has their own sound. You find it and you run with it. Like your voice. We all have similar things that we do with our voice when we talk, but we all have our own unique way of doing it, even if it's not dramatically different. But the thing that will get your personality out in music is writing, more than playing almost. So, I'm always writing.

What are some challenges you face in the writing process?

The hard part for me sometimes, when I write, is that I get shy about it. It's on a piece of paper, and you get voices like, “Oh, this guy is going to laugh about this, or this person's going to hear this and think it's stupid." I have to fight through shyness. If I feel like “this is dumb," and somebody laughs at the tune, tough shit. It's not the end of the world. You say, “What's the worst that can happen? So what? I'll write another one," or “I'll change that tune." And most of the time you get positive feedback.

I noticed you retired the Yamaha G-100.

Yeah, I finally retired it. I use these Roland Blues Cube things. This guy, Yoshi [Ikegami], that used to work with Boss a lot is now the CEO, and he's a good friend, and he hooked me up with these amps. I use it at the 55 Bar and I used it for the whole recording. Two of them for the stereo thing. I like the air and the space in my sound. That's why I use what I use, but these have a little bit more of a direct thing. I like the mids—there's a kind of clarity to them.

Guitars

Yamaha Mike Stern Signature model

Amps

Roland Blues Cube Artist 212

Effects

Boss DD-3 Digital Delay (2)

Boss BD-2 Blues Driver

Boss SD-1 Super OverDrive

Boss TU-3 Chromatic Tuner

Boss MO-2 Multi Overtone

Yamaha SPX90 multi-effects processor

Strings and Picks

D'Addario strings (.011, .013, .015, .026, .032, .038)

D'Addario heavy picks

D'Addario cables

How about the Pearce head you've used for decades?

I still use it, but only at the 55 Bar. I usually use Blackface Twins on the road because they're easy to rent and they sound good. I might start using the Blues Cubes though. I try to do new things all the time, but with equipment I like to lay with the same things that work. I'm not a real strong pedal guy—some guys are amazing with it. There's a lot of cool stuff but I like to minimize that. I still use the SPX90 [Yamaha], which is a billion years old. But I use it for one patch alone, #23, which is this harmonizer patch that has a nice, kind of chorus sound, but it's not a chorus sound. It's somewhat different. It fattens up the sound and gives it more air. I still use it, especially for quartet when there's no piano. I tried to get someone to make just a pedal of that sound, and they can't do it. I don't know why. It's digital. It should be easy. Someone who really knows about this shit told me that you can't get that sound in a pedal. I still have to lug that thing around.

Having had the chance to jam with you before, I've heard you play many things that I've never heard you do anywhere else. Do you find that in concert or on a recording, you gravitate towards playing in a “Stern"-style that people expect?

No, sometimes that just happens naturally. When it's time to perform, you don't want to go for too much or think about it too much. You're hearing the whole live picture. You're thinking, “Boy, the drums sound fucking great." So rather than think, like, “I can punch in here and do this new line," that's not what it's about. There are times when we'll play together and I'll go for new stuff. I've got books of all these solos [points to stacks of hand-written transcriptions] and sometimes they fit in a real setting, but sometimes they don't really fit, when you're thinking about the whole picture. You gotta go with your impulse and your judgement at the time rather than think, “I've been practicing this voicing and I want to use it here."

Within a couple of weeks after your comeback, you played several high-pressure, high-profile shows with Chick Corea and Kenny Garrett, who are, like, the best of the best on the planet.

That was rough. I was struggling. I didn't know how to hold the pick, exactly. There were times when it was totally cool but that was when I found out I had to find some other way to hold the pick. I remember I stepped on my cable twice and Kenny Garrett had to put it back in for me.

And since then you've played with guys like Ulf Wakenius, who is also a monster guitarist. Do you enjoy these types of challenges?

Sure. I love it. I used to play with [saxist] Jerry Bergonzi, and it's impossible to follow that cat. He has so much vocabulary and plays with so much dexterity, and swings so hard. I've always kind of put myself in situations where guys would kick my ass.

I guess having played extensively with Miles and Jaco Pastorius, as you did, will make anyone tough as nails.

No, no. They were rough personalities, but you get used to it. You can't be too precious about it. When you're writing music, it's really wearing your heart on your sleeve. That's why people sometimes are like, “Yeah, I'm a tough motherfucker." It's bullshit. Miles was a completely hypersensitive human being, and Jaco, too. Sometimes that's why cats get into trying to anesthetize themselves. It's a double-edged sword. You get this really beautiful gift so you're generally a little more sensitive, but the other side of it is that things hurt a little more.

The first jazz gig I ever did, I was really scared. It was at a tiny place in Boston called Michael's. Everybody that did gigs used to put up signs around Berklee to let people know they were playing, and I didn't even want to put any signs up. This was the first gig that was mine and I was so nervous. The pick was falling out of my hand because I was shaking so much. It was so scary for me to do a jazz gig and put my name up anywhere, so I almost didn't want anybody to show up. And no one did anyway, like three people were there—it was just a quartet and the band outnumbered the audience. By the second set, the guy said, “No one's here so you can split." I was really depressed after that. Then I said, “Well, I got nothing to lose so I'll try again." I think the second gig was actually worse, and then the third gig was a lot better. So, you just keep going.

Mike Stern tears it up with endless streams of long lines, all played at a blistering pace.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)