I only met Chris Squire once. It was just about as surreal as the Roger Dean paintings on old Yes album covers and, in retrospect, rather fittingly full of twists, turns, and humorous surprises. I say fitting because my first real exposure to what most hardcore fans would call “real" Yes—the classic lineup of the late legendary bassist, Steve Howe (guitars), Jon Anderson (vocals), Rick Wakeman (keys), and Bill Bruford (drums)—was a bit of an accident. I was 16 years old and lived in possibly the most conservative city in America, where I knew hardly any other rock musicians and pretty much everything I knew about music was from magazines.

Beyond & Before

I'm sure I heard Squire's rollicking Rickenbacker tour de force on “Roundabout" as a young child—but I wasn't even born till the year after the groundbreaking Yes hit was released. By the time I started playing guitar, Yes meant “Owner of a Lonely Heart" and the modern sound that guitarist Trevor Rabin brought to the band's '80s comeback albums, 90125 and Big Generator. I'd gotten into playing music because of Van Halen, so I liked the flashier approach and was only vaguely aware of the band's early work.

All that changed one night when I went to my bedroom, flipped on the classic-rock radio station from the nearest big city and, within seconds, was hooked by the intricate musicianship, ever-shifting compositional structure, and beautiful vocal harmonies of a song I'd never heard before. Something that most definitely wasn't from that decade.

Who is this? I wondered.

I assumed a DJ would come on and dispel the mystery at the end of the song, but instead another tune, clearly from the same band and album, came on. When the lead vocals finally came in, the distinctive, high-pitched voice sounded familiar, but I had to know for sure. I was mesmerized. Glued to the spot. I refused to leave my stereo's side for fear of not hearing the eventual revelation, because the adventurousness of this strange “new" music piqued my interests in ways I'd never experienced.

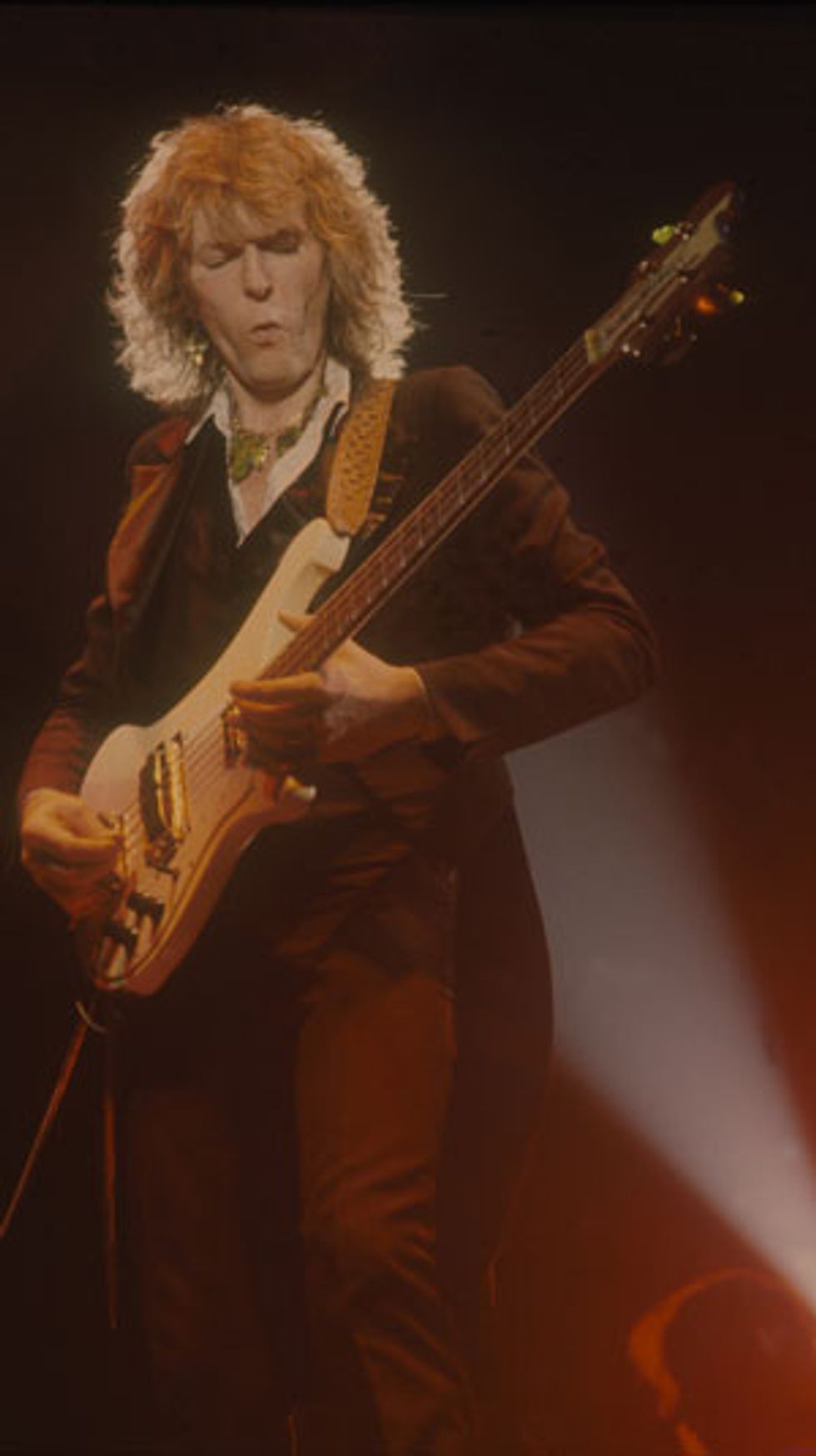

Yes bassist Chris Squire plays his longtime Rickenbacker 4001 in 1978. Photo by Neil Zlozower/Atlas Icons.

It soon became clear that an entire album was being played, and after sitting through a few more songs full of perfectly timed bass-and-guitar unison riffs, angular 4-string-vs.-6-string duels bouncing from the right speaker to the left, and crisp, brawny, in-your-face bass lines propelling each song forward with a masterful blend of technique, restraint, and melodicism, my suspicions were finally confirmed: It was indeed an earlier version of Yes, and the album was their 1971 masterpiece Fragile.

The next day I went out and bought the late-night mystery album, as well as Close to the Edge, and The Yes Album. In fact, my meager CD budget for the next couple of months was all spent on Yes albums: Their eponymous debut—which sees Squire just ruling the roost alongside original Yes guitarist Peter Banks (check out Squire's brutal, swirling intro to “Survival," and the swinging, upbeat beginning to “Harold Land")—plus Time and a Word, Tales from Topographic Oceans, Relayer, and Going for the One. It's an understatement to say I was a Yes freak.

Meeting the Fish

I first saw the band live on the Talk tour at Wolf Mountain, Utah, in July of 1994. To this day three memories remain strong: 1) How majestic and badass Squire was as he stood there in a long, flowing overcoat, throwing out complex, beautifully thunderous lines like a stoic, bass-wielding Zeus descended from Mount Olympus; 2) how Rabin nailed the tones and delivery of old Steve Howe songs; 3) and how Anderson's baggy, karate-like outfit and spoken-word interludes were pretty awkward.

Which brings me back to meeting Mr. Squire. It was March 14, 2013, and we were set to film a Rig Rundown with him and Howe before the band's Three Album Tour performance at the Holland Performing Arts Center in Omaha, Nebraska. Due to some sort of communications snafu, Squire and Howe were expecting to be interviewed in their dressing rooms. As we explained to the road crew that we needed to talk to the duo onstage so they could show and tell us about their gear, it became clear the concept of a Rig Rundown was foreign. But they obliged, had us wait outside a set of stage-left doors, and went to explain to the veteran interviewees why they couldn't sit in the privacy and (relative) comfort of their backstage havens.

Before long, Mr. Squire emerged and, despite the unexpected change of plans, was friendly and jovial. You can tell from the first few minutes of video footage that I was nervous—not just because I was meeting one of the most influential musicians of my youth, but because I knew I'd probably annoyed and inconvenienced him. But he handled it with grace, kindness, and humor. He showed us his hallowed 1964 Rickenbacker 4001, triple-neck Wal copy, '70s Jim Mouradian bass, and other cool instruments, going into great detail about changes to the storied gear and patiently answering (for the umpteenth time, I'm sure) questions that had to have been frustratingly geeky.

Squire never acted put out, but 13 minutes into the interview—after we'd covered a bunch of his road basses—he handed us off to his tech to finish talking about amps and effects. He kindly but decisively explained that he needed to go get ready for the show … which was about three hours later. But no matter—I was just glad he'd spoken to us at all. He'd been a bass god for more than four decades and had no need for extra publicity.

I only wish I'd stayed for the show that night instead of letting a long drive and a heavy load of work back at the office dissuade me. Squire seemed strong and in good health, with years of recording and touring still left in him.

Starship Trooper

Christopher Russell Edward Squire, born in Kingsbury, London, on March 4, 1948, passed away June 27, a little over a month after being diagnosed with a rare form of leukemia. Like his heroes John Entwistle, Jack Bruce, and Larry Graham, he leaves a matchless musical legacy. He wasn't just a bassist's bassist—he was a complete musician with an instantly identifiable sound and a keen ear for dynamics and melody. Rest in peace, Mr. Squire. You've left this world a better, more wondrous place.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.