The playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht once observed that “art is not a mirror held up to society, but a hammer with which to shape it.” If that’s true, then perhaps Boris, with its blend of experimental, stoner, sludge, doom, and hardcore sounds, is such a hammer—at least among the cognoscenti of unrestrained, cutting-edge rock.

The band was named and, originally, sonically styled after an epic eight-minute Melvins jam. Three decades later, Boris’ sound has evolved into a furious emotional tumult that—during a time of pandemic, worldwide social unrest, and devastating climate events—seems to capture the anxiety, fear, anger, hatred, and uncertainty that is reverberating.

It’s in the DNA of songs like “Genesis,” the primordial, unsettling opening instrumental track of their latest album, NO. Is it cueing the end of the beginning or the beginning of the end? Is it a dirge or an anthem? The visceral response this overture evokes sets the tone for the rest of NO. That Boris is able to convey such a cathartic experience with their music is no small feat. That kind of transcendence only happens when the message meets the moment. And for Boris, NO is the message, and 2020 is the moment.

Formed in Tokyo in 1992 as a four-piece, Boris quickly transformed into a genre-blending, avant-garde power trio after their 1996 debut, Absolutego, on the Fangs Anal Satan label, when singer Atsuo Mizuno took over on drums for their original drummer, Nagata. Absolutego was an exercise in Melvins-inspired drone rock and featured a single 60-minute track. The 1998 follow-up, Amplifier Worship, diverted sharply into psychedelic and jam-band territory. In 2005, Pink, arguably Boris’ commercial breakthrough, featured mostly short, concise songs in a shoegaze and post-rock style. Pink met with considerable critical praise, with both Blender and SPIN magazines naming it one of 2006’s best albums.

Collaborations with other experimental musicians and artists, like Keiji Haino, have also been a hallmark of Boris’ career, and in 2009 they appeared on the avant-metal soundtrack to Jim Jarmusch’s film The Limits of Control. Just last year they released their 25th studio album, LφVE & EVφL.

Boris’ musical journey has been guided by a faith in the deep interpersonal conversations that playing music in a band offers—an important core value of their DIY ethos. In the studio, they record themselves: placing their own microphones, mixing their albums, prompting their own sonic experiments. Their focus and genuine curiosity about craft propels a deep commitment to process, rather than results. They are invested in the work that their explorations demand, not the fame they may ultimately derive from it. And much like jazz musicians, they’re most committed to the musical conversations that happen—among themselves and with their audience, live and in the moment—so rarely do they ever play the same composition the same way.

It shouldn’t be surprising that this band with almost 100 releases to their credit—including EPs, reissues, singles, live albums, and collaborations—was able to create NO in a matter of weeks. “We reserved our room and rehearsed and recorded there after the lockdown,” says guitarist/bassist Takeshi. “We began on March 24 and completed recording three weeks later.” If anything, a global pandemic only served to make their mission more urgent and focused—or at least fueled their apocalyptic aesthetic.

NO, like Pink, features shorter, more terse up-tempo numbers than the long, droning jams that have been Boris’ most recognizable trademark. Only three of NO’s 11 songs are over five minutes. (Opener “Genesis” is among those three.) Song length, however, is basically where the comparison to Pink ends, as NO is a much heavier album. Entries like “Anti-Gone,” “Lust,” and “Loveless” feature fierce, fast-paced riffs that wouldn’t sound out-of-place on a Motörhead album. According to Takeshi, this is the result of interacting and sharing bills with Japanese hardcore/punk legends, including Gastunk, the Genbaku Onanies, and Narasaki (of Coaltar of the Deepers), during the Japan tour for LφVE & EVφL in February.

“I was able to reaffirm my roots with music that was hugely influential when I was a teen,” Takeshi explains. “After that tour, the world gradually became terrible due to the new coronavirus, and, not being able to tour or perform live, the only option we had was to create an album to deliver to listeners. During the studio sessions, the sound imagery became fast and noisy according to the manners of hardcore punk. We usually do not set any rules for recording, but just like listening to hardcore punk healed my anxiety, hatred, anger, and sadness when I was young, and hope was born, we’re hoping that NO, as an extreme music, will heal listeners who live under the threat of the coronavirus.”

In addition to Takeshi and Atsuo (who also serves as the band’s recording and mixing engineer), Boris features the mighty Wata on guitar and keyboards. Wata might be the most introverted of the group, but her gargantuan tone, deft melodicism, and kinetic riffs entrench her in the same conversation as High on Fire’s Matt Pike or Gojira’s Joe Duplantier—together, a triumvirate of doom/stoner-era guitar gods. But Wata rarely speaks publicly about her work.

PG recently caught up with Takeshi and Wata, who were at home in Tokyo. With the help of translator Kasumi Billington, they both opened up about their creative processes, guitar interplay, gear, influences, and much more.

How integral are jam sessions to Boris’ creative process? Were the songs on NO born strictly out of jams, or did any of you bring fleshed-out songs into the studio?

Wata: Boris’ songwriting and recording is generally in the form of jam sessions. We rarely compose in advance. It’s rock ’n’ roll, so it’s not interesting unless the sound rolls on the spot and unpredictable events occur. Amp settings and volumes are also important elements to our compositions. A song won’t reach completion unless it’s actually played in the studio with loud volume. There are songs that are born because they are loud.

TIDBIT: Although Wata also plays keyboards in Boris, their new album is guitar-only, crafted from practice-space jams spearheaded by her and Takeshi. “It’s rock ’n’ roll, so it’s not interesting unless the sound rolls on the spot and unpredictable events occur,” she explains.

Takeshi: There are times when we write songs in advance, but it’s mainly like a memo of an idea [for a song]. As usual, NO started from jam sessions at the studio.

What elements of a jam are you listening for, or cultivating, to help guide the formation of a new song?

Takeshi: We are guided by phrases and melodies that are born from our jam sessions. Rather than composing, it’s more like the sensation of drawing, but guided by sound. That’s the method that feels natural for us, to be able to create work comfortably. The important thing when recording is to keep an environment free of stress for the members—to be able to see each other’s faces, and to be able to resonate sound in the same space and atmosphere.

Boris has been around long enough to make albums using both analog and digital recording. What is your preference?

Wata: Equipment-wise, I like analog, but recording is easier with Pro Tools. Sometimes rehearsing while we adjust the monitors ends up sounding better than the actual recording during the main production. We have taken that into consideration recently, and now record during rehearsals as well. There are many times when the recordings taken during rehearsals are used instead. Since there’s no recording cost, digital recording is suitable for this type of production—one that has a strong documentary element.

Boris employs drop-tuning to great effect. Do you have a preferred tuning to write and play in?

Wata: In general, we tune three steps down. I also like tuning where we drop the 6th string to D#. The expression of choking and vibrato changes when you play the 5th and 6th strings together. When playing riffs with Takeshi in unison, each playing style creates different waves, and adds depth to the sound. There are restrictions when using various tunings, but there are also songs that can only be created with that tuning. I want to keep trying various things.

Boris has a very DIY ethos. What was the studio set-up like for NO, including your signal chain?

Takeshi: The place where we always record is a rehearsal studio we’ve been using for years. There’s no mixing booth. We self-record by bringing recording equipment to that same room. We set up the microphone stands ourselves, and everything is DIY. We try not to increase the number of tracks we record, but, for the guitar recording, we simultaneously record signals from both a mic (Sennheiser E606) and a DI (Countryman Type 85). When we mix, we have options to combine the two or use either alone. We’re always sure to record the sound of shaking air with the microphone.

Wata and Takeshi both play guitar in this live video from 2017, with plenty of banshee-wail EBow and the distinctive, guttural howl of low-tuned axes overdriven to the max.

With his First Act guitar/bass hybrid, Takeshi can cover the sometimes rapid tonal and dynamic shifts in Boris’ music—or simply stay in the heavy zone with a combination of low tunings, pedals, and high-headroom amps. Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

What guitars and amps did you mostly use?

Takeshi: On this recording, I used the tremolo arm heavily, so my main guitar was the B.C. Rich Warbeast. To record the bass, I used my First Act Doubleneck bass/guitar. For the guitar amp head, I used my Sunn Model T with an Orange PPC412 cabinet during recording. To record the overdubs with noise guitar, I used a Roland JC-120, which produces a flat range, from low to high frequencies.

What about bass?

Takeshi: I used the Orange Terror Bass for the bass amp head and an Ampeg 810E cabinet. The pedal used this time for the [core tone] guitar was a Dwarfcraft Devices Baby Thunder fuzz, and, for the bass, a Death By Audio Apocalypse fuzz was mainly used, with reverb slightly added, and additional fluctuations with an EarthQuaker Devices Aqueduct vibrato.

Wata, what was your signal chain in the studio while recording NO?

Wata: In the last few years, we’ve used the Sennheiser E606 microphone on the cabinet. According to Atsuo, he’s able to capture finer dynamics than the standard SM57. We tune three steps down from regular tuning, and the sound is extremely distorted with fuzz, so this mic, that captures fine nuances, seems to be a good match. I always use Countryman’s DI Box to record direct signals. During the mixing, we may use an amp simulator for the DI signal. In general, with the pedal effects applied, we also make sure to ring the amp when recording. Atsuo says that recording without feedback takes away the purpose of using an electric guitar.

Takeshi, what is the origin of your doubleneck bass/guitar?

Takeshi: I initially bought one around 2001. We released a 70-minute, single-song album called Flood around the same time, and I had to switch between guitar and bass when playing. It was troublesome to switch and lose time, so I got an SG-style doubleneck made by Starfield [an Ibanez brand]. But since it was a short scale, it didn’t produce much low sound, and since the body itself was heavy and big, I didn’t like it much. It was also difficult to carry around on tours, so I later bought a Spirit, by Steinberger. It was compact and suitable for tours, and the sound was solid and pretty good, but I still didn’t like the shape much. My favorite bassists—Geddy Lee from Rush, Chris Squire from Yes, Cliff Burton from Metallica, and Lemmy Kilmister from Motörhead—generally used Rickenbackers, so I was hoping I could get a custom one someday that was similar to the Rickenbacker shape. My friend from college had been to a musical instrument making school, so I had him create a basic drawing.

How did you hook up with First Act, for the Boris signature double-neck?

Takeshi: At some point, [bassist] Nate Newton from Converge introduced me to First Act. We’ve been friends for many years. He had a Mosrite-shaped custom bass created through First Act. During a Boris U.S. tour, I went to First Act’s office in New York City and met [artist relations director] Jimmy Archey.

He enthusiastically listened to my difficult request and was willing to accept the production of this custom doubleneck. He’s now left First Act and runs an amazing guitar shop called 30th Street Guitars in New York. He still comes to Boris’ live shows. If I didn’t have this relationship and encounter with Nate and Jimmy, my double-neck may not have existed.When I first started playing a double-neck, it felt strange, but now I’ve gotten used to it.

[Editor’s note: Takeshi’s custom First Act bass and guitar doubleneck has a mahogany body with a maple top, two maple necks with rosewood fretboards, a Badass bridge, and Gotoh GB707 bass tuners and Sperzel 3x3 Trimlok guitar tuners. The bass side has a Seymour Duncan SJB-3 Quarter Pound J bass pickup in the bridge and a Duncan SPB-1 Vintage P bass neck pickup. The 6-string side sports two Seymour Duncan ’59 Model SH-1 pickups.]

Since you play bass and rhythm guitar, how do you decide which one to apply to a song or a section of a song?

Takeshi: I originally played the guitar, so even during jam sessions it’s easier to come up with ideas when playing the guitar rather than the bass. When I begin to make a song, most of the time I’m using the guitar. Whenever there are songwriting sessions, we play through the guitar amp along with a bass amp, so the guitar covers the bass-frequency range. Boris tunes three steps down, so Wata and I could be called a twin baritone guitar formation. As the riffs and melodies are built, the song will tell me if I should add the bass.

Can you please clarify which songs on NO feature bass?

Takeshi: The songs I played bass on are “Anti-Gone,” “HxCxHxC -Perforation Line-,” “Kikinoue,” and “Lust.” On “Loveless,” I only play the guitar, but, by dropping the 6th and 5th strings, I created a sound image where it seems like I’m back and forth between the bass range and the baritone guitar range. I can’t create that kind of ambience just by playing the bass normally. Interesting effects were born when I tried this out in jam sessions, so this song ended up without a bass.

Wata, the EBow has become a signature component of your style. How did you discover that tool and what makes it a go-to part of your musical arsenal?

Wata: I started using it during Absolutego. I brought it in because I could get the drone pitch without being bothered by howling. Once I began using it, I was impressed that the EBow not only produces a continuous sound, but also allows a very wide range of expression by moving it closer to, or further from, the strings, and also by changing position, adjusting the left hand, and by using effects. It’s a simple but extremely profound, organic piece of equipment.

How do you decide between guitar or keyboards on a particular song?

Wata: I’m the only one who plays keyboards, so there are times when I may be in charge of the keyboard and accordion, based on the show’s color.

Since we sing as we perform, there are times when the instrument I’m in charge of changes for the song. We didn’t use the keyboard for NO.

Photos by Miki Matsushima

BASSES & GUITARS

AMPS

STRINGS, PICKS & CABLES

| EFFECTS

|

Wata’s 6-strings of choice are Gibsons, and she tours and records with a pair of ’80s Les Paul Customs and two late-’60s SGs. Orange amps and cabs also figure prominently in her sonic calculations. Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

Specifically regarding guitars, how do you divvy up your roles in Boris?

Takeshi: There are times when we divide our roles based on the song, but in general Wata is the lead guitar role—her guitar sound adds glitter and stretch to the song. One of Boris’ musical elements is the phenomenon of intentionally mixing our two sounds in unison and interfering with the low frequencies to create sound waves.

Wata: Takeshi is good at hardcore, thrash-like rhythm guitar playing with a sense of speed and twist. He’s great at using effects and is good at creating sounds with noise and spatially expansive sounds. He’s also mastered multi-effects. I try to play a simple and memorable guitar melody, paying attention to parts between sounds, through sustain, feedback, choking, and vibrato.

How do you prevent the low end from dropping out when you switch from bass to guitar?

Takeshi: There are times when Wata has the lead and I switch to bass, and there are songs when I play bass the whole time. When switching from bass to guitar, I have a setup where the guitar signal can output through a bass amp, so the bottom end does not weaken. There are times when I play lead, so, in that case, the roles are reversed.

I think “Loveless” demonstrates the kind of traditional rhythm/lead roles you both sometimes occupy in Boris and are integral to the construction of that song. How do you decide on the interaction of your instruments, between rhythm, lead, bass, and keyboards?

Wata: It depends if he is the center of a composition or I am at the start of a composition. The arrangements are made making the best use of each person’s characteristics. There are times when we arrange songs based on how we imagine the three of us playing onstage. For “Loveless,” Takeshi created the riff, and then we created the lead and melody together. Atsuo is in charge of the sound production, so the three of us will come up with ideas and move on. Even though it’s a three-piece band, many opportunities are born. In the recording for NO, Takeshi plays a majority of the rhythm.

What’s your approach to crafting solos?

Wata: I kind of form an image in my head, but most of it is improvised. Sometimes it’s determined after recording a few takes, and sometimes it’s arranged again based on a recording take. When playing live, we use the recording as the starting point, and add in the feelings and emotions at that moment, and change is born.

Takeshi, you earlier mentioned Chris Squire, Cliff Burton, and Lemmy Kilmister as influences. What is it about their playing that you like?

Takeshi: I like bassists who play with a distorted guitar-like tone—it’s that sort of influence.

Wata, do you have any specific influences who helped shape your approach to guitar, or any formal training?

Wata: A guitarist I was influenced by is David Gilmour of Pink Floyd. I was taught a little around the time I started guitar, but self-study, playing in bands, became the main constituent quickly.

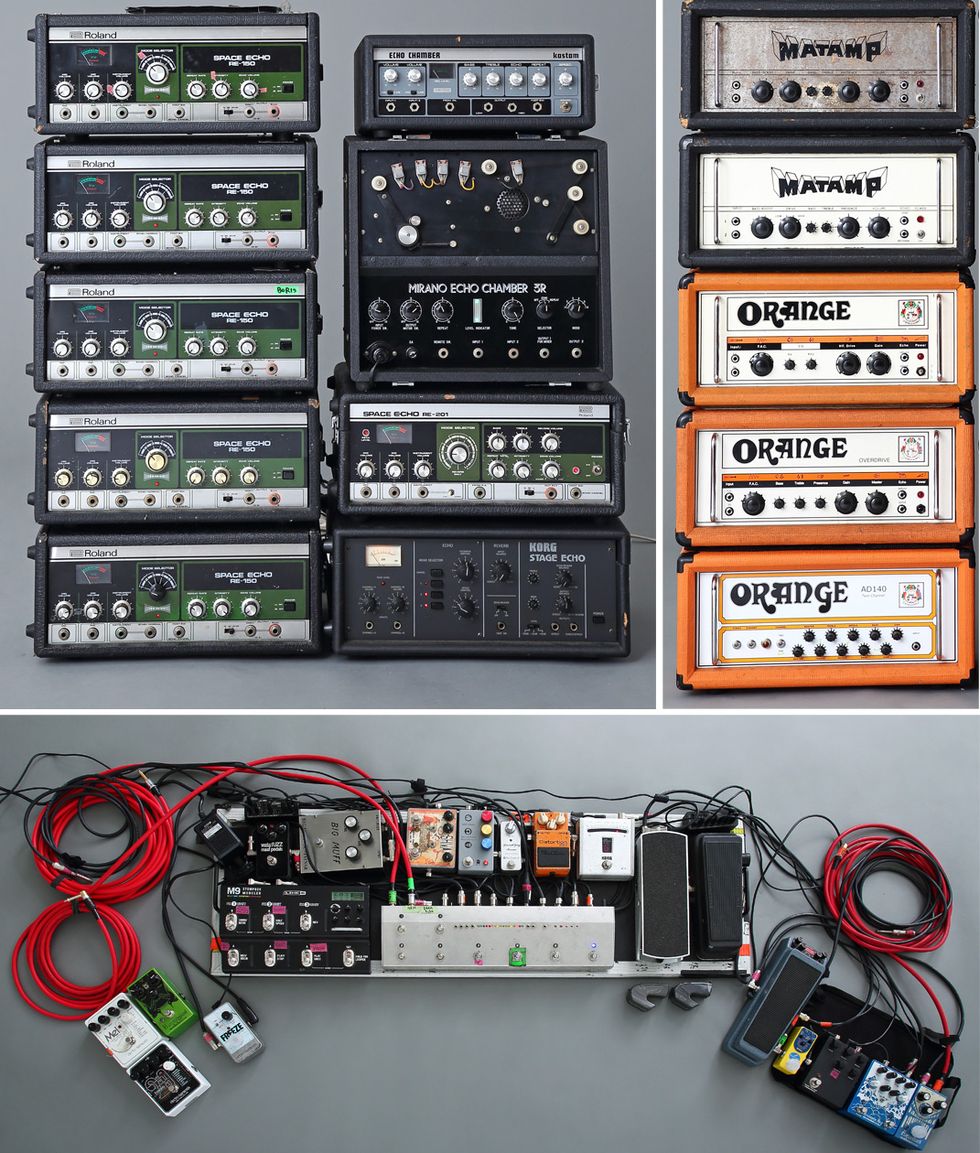

My encounters with equipment such as Orange amplifiers, the Roland Space Echo, the Elk fuzz, and the EBow have influenced my style significantly. It’s also important to have loud volume that can create feedback. The Roland Space Echo RE-150 is so important to me that I even bring it along on our tours. The damage-like feeling peculiar to analog tape, the fluctuation that feels like it plays automatically—it gives me great power when performing. It feels like the tape echo is performing with me. Additionally, there are times when various ideas are born when I experiment with various effects pedals that I obtained.

Are you working on any technical aspects of playing at the moment?

Wata: I don’t do much training now. I’m not interested in playing fast or accurately, and I focus on reaching the hearts of listeners who hear the music under various situations. There’s no answer to music or these artistic expressions, and I think each person has to work their own way to get an answer unique to them.

Did Japan’s visual kei movement—which uses makeup, costumes, and other design elements as part of a musical presentation—have any effect on your playing style?

Wata: When I started playing the guitar, there were many bands that were active who’d later be referred to as roots of visual kei. Many of my friends at school and those senior to me were in a genre close to visual kei, so I often went to live shows. The tone of the guitar is very different, but the influence at the time was great as a musical experience, even if it wasn’t direct. I’ve been influenced in aspects such as simple and strong riffs, melody work, etc. As an element of music, “visual” is extremely important. If the amplifier is orange, the impression of the sound becomes completely different.

Is there any piece of equipment you use that’s essential or particularly noteworthy that wouldn’t be obvious to the average listener or fan?

Takeshi: About 80 percent of the time, in the last few years, Wata and I have been making twin guitar sounds, and I haven’t played the bass. The sound making is mostly with guitar. Onstage, I use the Bright Onion pedal’s phase/ground switch pedal a lot, so the phase of each amplifier and speakers are aligned with this equipment. I’m able to create stronger volume and sound pressure. This is basic, but extremely important.

Anything else?

Takeshi: For me, the Sunn Model T sound character is essential. That loud volume and unique low-end feel can’t be obtained through other amps. I have about five vintage ones from 1973 to 1975, but each amp has slightly varying sound, and it’s interesting. Previously, I used the second generation from 1974, but this one has a dark, slightly muffled sound. The main one I use right now is the 1973 first generation. This one has reasonable crunch and bright sound. It also has a good, balanced range.

Wata, do you have any secret weapons?

Wata: The Soul Power Instruments two-in, four-out, eight loop switcher. This switcher was custom made for me. With a single switch, I can change the settings of two-in for guitar and keyboard, and four-out for output to multiple amplifiers. Depending on the song, I can control the number of amplifiers used and the volume. It’s as though we touch and communicate with the audience through sound, so it’s important to be able to control the strength and weakness level of that sound.

Are there any songs on NO where effects were an essential inspiration for their creation?

Takeshi: “HxCxHxC” has guitar play that uses extreme reverb and delay. The jam we recorded had drums sprinting through a sound space where we couldn’t understand the chords and melody, and the balance was really interesting. We later added a bass line, and it became a song. To maintain our fresh feelings, we like trying out new pedals and amps, so there are times when we also gain inspiration from those timbres and effects. It is fun trying out various kinds of equipment.

What’s the secret for crafting a cohesive sound without being pigeonholed into a particular style of music?

Takeshi: On the surface, listeners may feel that the albums or songs are disjointed, but we’re not consciously trying to challenge ourselves each time to do something different. We’ve been searching for our meaning of “heavy” by consolidating the feelings we’ve gained in our lives, the musical experiences, and means of expression. During this journey, we find something new, and that’s one of the things that motivates us to keep creating work. From the beginning, this fundamental part of Boris has not been shaken at all.

Photos by Miki Matsushima

GUITARS

KEYBOARDS

AMPS

STRINGS, PICKS & CABLES

| EFFECTS

|

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)