It's clear from the first few lines of Juliana Hatfield's bold new album Pussycat that this is a record with a mission statement. In today's political climate, it's easy to guess the intended target of songs like “When You're a Star," “Kellyanne," and “Short-Fingered Man." But what makes this rich 14-song collection more than just a momentary reflection of the times is that Hatfield rarely succumbs to sloganeering or naked attacks (the song “Rhinoceros" being one notable exception). Instead, her words vividly illustrate the personal impact of attitudes and behaviors in stark, often jarring terms. The issues she tackles existed before 2016 and will continue long after Twitter ceases to be the bully pulpit.

Lyrical messages, no matter how cleverly drafted, don't resonate for long without a musical framework. And Pussycat delivers there, too. Hatfield built her alt-rock bona fides long ago by being simultaneously tuneful and surprising. Both qualities are in full supply here. Starting with “I Wanna Be Your Disease," the songs grab your ear before moving in unexpected ways, making you want to go back and listen again.

Written and recorded quickly, with Hatfield performing everything but drums, Pussycat is also a showcase for her deft rhythm, lead, and bass guitar playing. Using a surprisingly small arsenal of gear (sometimes aided by a Korg keyboard synth), she creates a range of textures—jangling chords, slamming riffs, and syrupy melodic solos—that sit perfectly with her voice and sometimes serve as a counterpoint to the sweetness of her vocal harmonies.

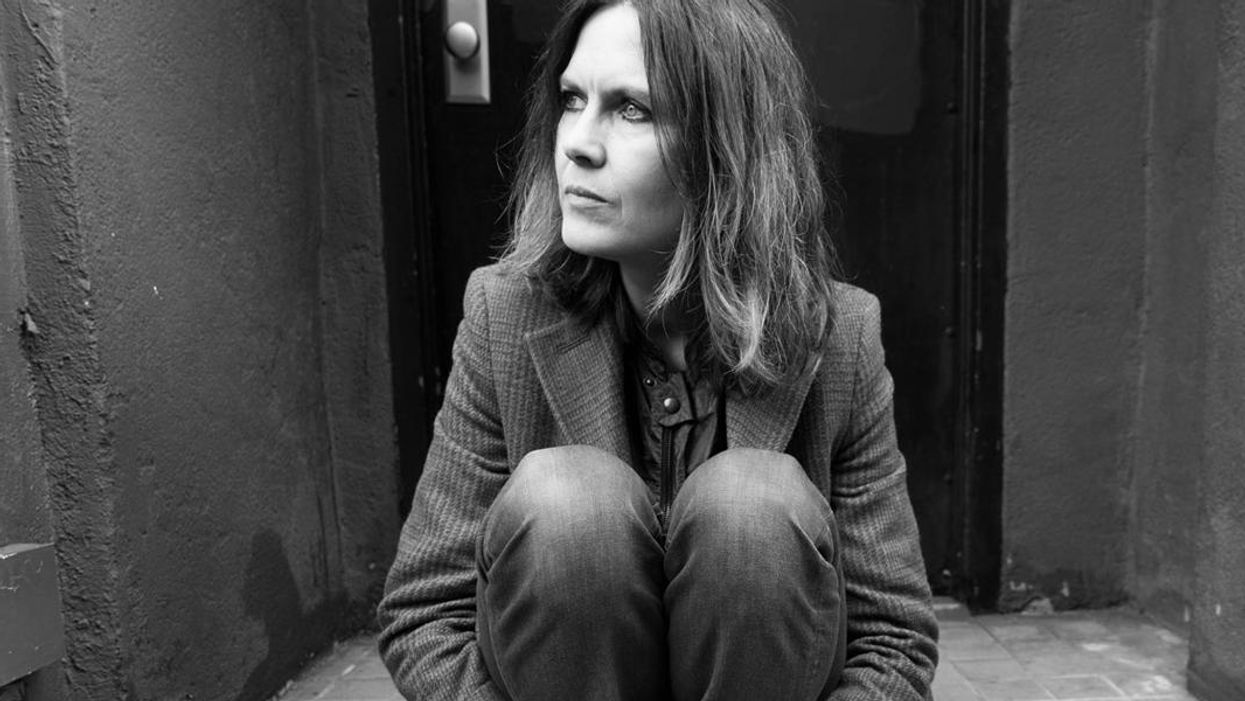

As a classically trained keyboardist and Berklee College of Music grad who emerged as a bass/guitar/vocal pioneer in the indie scene in the days when they called it “college rock," Hatfield has always been an artist of many layers and contrasts. And despite the intensity of her subject matter, she was soft-spoken and introspective when we caught up on the phone earlier this summer. Then again, she's never had to shout to get her message across. And as always, her guitar speaks loudly when she needs to wield the axe.

You wrote and recorded the songs on Pussycat in just a few weeks. Is all the material new or were you drawing on the archives?

Musically, there was stuff I was taking from who-knows-when. I have these cassettes just filled with ideas. I'll sit down and turn the cassette recorder on and start playing guitar—just endless little bits of things developing in real time. So I was going back to things from a couple of years ago or even more. But at the same time, I was coming up with new things on the spot. It was a bit of everything, just trying to note anything that caught my ear. A lot of things I'd discarded in the past, I listened to with fresh ears. Anything that stood out, that was catchy or gave me pleasure in any way, I was like “I'm gonna use that!"

How did the relatively short production cycle influence your approach?

I did a lot less second-guessing than I normally do—a lot less thinking and self-editing. I just grabbed anything I thought was cool and worked with it. I was a lot more open to using things that in the past I might have thought weren't interesting enough. I learned that I haven't always been the best judge of what's good or bad because I'm happy with all the music I chose from the archives.

To track Pussycat, Hatfield booked time in a pro studio. “I wanted to do it away from home where I couldn't afford to waste time," she says. “I have a tendency to over-think things and over-rehearse, and that can kill the spark."

When I'm recording my guitar into my Walkman, you never know how things will turn out once you add drums and bass. I was really working on faith. I think that was a good lesson to myself—if you have the right attitude and believe in it, you can make anything work.

The songs are catchy, but they often go in surprising directions. How do you unlock those ideas?

I have two acoustic guitars I use for writing. One is in normal tuning, the other is in “weird" tuning. I'm too lazy to retune when I'm writing, so I just keep one of the guitars in “weird" tuning. A lot of the songs were written in that tuning, which is C–G–D–G–B–E.

How did you come up with that one?

I stole it after I tried out for a band called Verbena when they were looking for a bass player a long time ago. They'd made a record called Souls for Sale, and I was madly in love with it. I learned all the songs, and [Verbena guitarist] Scott Bondy showed me all the songs with this tuning. I borrowed it from him and I love it. Having a different tuning helps kick-start the writing.

The first three songs [“I Wanna Be Your Disease," “Impossible Song," and “You're Breaking My Heart"] are all in that C–G–D–G–B–E tuning. I have to use my left hand in a different way to make all the notes work, and that limits my fretting. There's not a lot I can do with my finger shapes, so I'm just moving up and down the neck and trying to find somewhere else to go—sliding around on the neck trying to make the song move. The limitations of the tuning really opened up the songwriting in a way, which proves my theory that limitations can be really freeing.

Do you use an extra heavy string for that low C?

I don't do anything special, and I never deliberately tried to make it less floppy. But I did switch to .011 gauge sets in the past couple of years on the electric. I used to use .010s.

These days Juliana Hatfield is down to two guitars, one of which is this late-'60s Gibson SG Custom she's owned for years. Photo by Matt Condon

You played everything on the album except drums. It can be hard to declare something “finished" when working alone. Was that a problem?

It was kind of opposite. One of the obstacles was financial. I was in a real studio [Q Division in Somerville, Massachusetts], where I couldn't afford to waste time. At home, it's different—you can take as long as you want. Part of why I wanted to do it away from home was so I'd have to go fast. I wanted to record in a state of only semi-consciousness, so my instincts would be working on overdrive. I have a tendency to over-think things and over-rehearse, and that can kill the spark. At the same time, I knew exactly what I wanted to do. It's not always like that for me. I think being alone made me feel more confident.

Why is that?

When there are other people around I'm too polite not to take in their opinions. But a lot of times, I end up trying out their ideas and think, “Eh, my instincts were better." This time there was nothing stopping me from obeying my instincts. I just went in and got it done. Knowing what I wanted didn't mean I had everything mapped out. It just meant that I was hyper-tuned into my instincts and let my unconscious work really efficiently. I felt I was obeying my muse.

It's interesting that the “go-with-the-flow" music is underpinning some very topical and often biting lyrics. Were they written before you started?

Not all of them. There were a few songs I had to leave to the end to sing because I was still working on the lyrics. The lyrics for [final track] “Everything is Forgiven" came together at the very last minute.

make anything work."

That's interesting, because “Everything is Forgiven" seems like a coda to the whole album—a response to the anger in the rest of the songs.

Yeah, it's the one song where I'm not exactly sure what I'm saying in it! I'm sure it's already been misinterpreted. It's probably more personal to me than some of the other ones.

Speaking of interpretation, listening today, it's pretty clear you're addressing the current administration in several of the songs. But if you remove that context, a song like “Kellyanne" might just come across as a generally frustrated relationship song.

I was worried about that and also the song “Rhinoceros"—which mentions Melania [Trump] by name. But with “Kellyanne," it occurred to me that kids born now might listen in 20 years and think, “Oh, this is a cool song!" It wouldn't matter that they don't know who Kellyanne Conway is. It's just a song about a complicated relationship with someone, and one in a long line of songs with women's names like “Rhiannon," “Michelle," and “Roseanna."

“Rhinoceros" has some very dark and vivid imagery about sexual violence.

Yeah, I still do worry about that one—maybe I shouldn't have done that second verse. But I did it and I have to live with it.

There are also some more universal themes in that song.

I know—that's why I worry. Did I cheapen the song by putting it into such a specific context in that verse? I don't know. I could re-record the lyrics for that verse for a future re-release. But I think it does serve a purpose. It's like a little nudge: “Hey, just so you understand where I'm coming from."

Juliana Hatfield's Gear

Guitars2010 First Act Delia LS with P-90 pickups

Late-'60s Gibson SG Custom

Amps

Circa 1965 Ampeg Reverberocket

Circa 1965 Gibson Skylark

Effects

ZVEX Fuzz Factory

Fulltone OCD

Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer (2)

Boss TU-2

Strings and Picks

D'Addario XL-115 (.011–.049)

Fender 351 mediums (.73 mm)

I deliberately put it toward the end of the album because I thought it would be too much at the beginning—too obvious or guiding people too much. I wanted people to find their way to that song. It gives people who are turned off by the subject matter time to abandon it before they get to that song. Overall, the imagery is kind of disgusting and some people probably don't want to deal with it.

Jumping back to making use of those idea tapes, do you enjoy going through all that material?

I don't do it for fun. If I feel the need to write songs, I go back and listen for work purposes. There's a lot of junk on there—minutes and hours of that. But when I do sit down and listen to those tapes, it's always so interesting. There's stuff I have no memory of having played and I have to figure out how I played it. Sometimes that takes a while.

Do the parts you write on acoustic guitar change as you bring them over to the electric?

Not so much the parts themselves, but how I play changes. I might play fewer notes or look for ways to get a different effect.

How did you record the basic tracks?

I played an electric guitar with the drummer, Pete Caldes, who's recorded with me before. I was intending those to be scratch guitar parts, but we kept some of them.

Once the drums were down, did you add instruments in a specific order?

I had everything around me—guitar, bass, and keyboard—and would just go around from one thing to another and do what I felt needed to be done at any given point. I started recording a bunch of guitars, and a song would say to me, “I want bass!" Other songs would say, “I need a keyboard!" and I would suddenly hear a part in my head.

Hatfield performing with her custom P-90-equipped First Act Delia LS. “They made it for me a few years ago and it has become my favorite guitar," she says. Photo by Joshua Pickering

The song “Sunny Somewhere" sounds like you wrote it on the bass, which is prominent in the mix.

It was miraculous to me how that bass line came together. I had guitar chords and a melody, but then when I picked up the bass, the part just happened. And I recorded it so fast. It was like, “Boom—done!"

Aside from the riffs themselves, the guitar tones stand out—sort of a mix of Sabbath-style grind with more modern textures. What electrics did you use?

I was using a lot of my First Act Delia LS guitar, which has two P-90 pickups. They made it for me a few years ago and it's become my favorite guitar. I got rid of most of my guitars a few years ago and now all I have is this First Act and a Custom SG from 1968 or '69, which I've had for like seven years. Those are my only two electric guitars, and I think they were the only ones in the studio. Unlike when I'm writing, I retuned each one as needed for different songs.

I sold my other guitars because I'm not a collector at all. I don't keep stuff just to keep it. I get tired of things and have no problem letting go. I described it to a friend as a relationship: For years and years my main guitar was an SG Firebrand—it was like an extension of me. But then one day I woke up and looked at the guitar and thought, “I don't love you anymore," and I sold it. Just like that. It was over. I was over it. For years, I was experimenting and trying to decide what I liked best. I've finally figured out what sounds I like.

I wouldn't call the sound “retro," but there's a vintage vibe to the guitar tones. What amps did you use?

An old Ampeg Reverberocket that belongs to the studio. I always use it when I record there because I love it so much. There were also three little amps set up next to one another, and I also used a Gibson Skylark. But, aside from the Reverberocket, if it's not my own gear, I don't pay attention to equipment. Instead, I'm more focused on whether I like what I hear. There's only so much space in the brain for tech things.

How did you get that heavy “broken-speaker" fuzz sound on “Wonder Why?"

That's a bit of gear I do know: the ZVEX Fuzz Factory pedal. They have a couple at Q Division studio and I finally bought one for myself. I just love it. I used it a lot on the album—it's really good for soloing. It's got a gate, which lets you get a heavy sound but with no sustain. It just cuts off at the end, like [makes a short tire-screeching sound]. I just love that effect. It makes it sound like the amp is breaking apart.

“Touch You Again" and “When You're a Star" have very distinctive riffs. Were they part of the song from the beginning?

Riffs usually come later. On “When You're a Star," we had the guitar and bass recorded. Then with that riff, it was like a light bulb going on over my head—I ran into the tracking room and recorded it. That happens a lot. The song will be recorded and I'll hear a riff, melodically, in my head. I just have to transfer it from my brain onto the guitar.

Do the vocal melodies come first?

Not always. Sometimes songs start with just chord progressions. But usually, once I have any kind of chord progression, the melody comes also. I often have melodies written ahead of the lyrics, which makes lyric writing more difficult because I have to fit them into these melodies.

I'll get attached to sounds and then it takes a while for me to wrench my brain away from that and realize it's okay to get unstuck. There were a couple of songs on the album where I was really stuck. “Everything Is Forgiven" moves around a lot. It was hard to fit words into that melody.

Sometimes I have a title and a melody, and I'm like “I've gotta get this goddam title in there!" “When You're a Star" had to use those words: “When you're a star, they let you." It was like a puzzle. I figured out the only way to make it work was to change the order of the words around.

“Sex Machine" and “Kellyanne" have longish instrumental outros. It's almost as if there's more to say, like you're mulling over the conversation in your mind.

I don't know why I did that, but maybe it's what you're suggesting, as if I need to ruminate on this a little more, or groove on it, and get it out of my system. It's also a kind of celebration—trying to make something good out of complicated issues—like you want to play music and make it all better and it's hard to stop.

YouTube It

In this live-in-studio performance, Hatfield shifts between jangle and grit on her beloved late-'60s Gibson SG Custom.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)