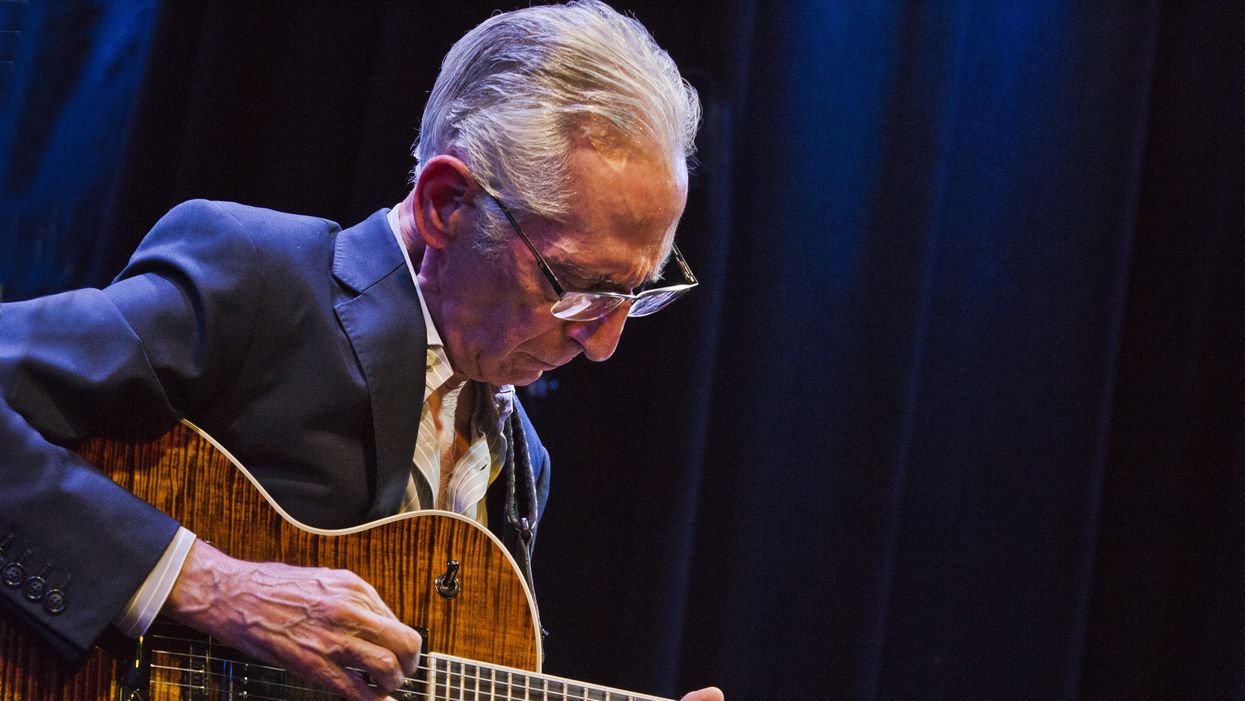

Walter Becker was a skillful guitarist who left an indelible trail of classic performances across Steely Dan recordings like “East St. Louis Toodle-oo” and “Black Friday.” But he was also a rarity among star players, always willing to divert the spotlight to others to achieve what he felt was the best result for the songs he and his partner in the band, Donald Fagen, envisioned.

Because of that, Becker, who died at age 67 on September 3 from a cause undisclosed at press time, helped make Steely Dan an incubator for a host of guitarists in the early ’70s, including Denny Dias, Jeff Baxter, Elliott Randall, and, perhaps most notably, Larry Carlton. Even Rick Derringer made occasional appearances on the band’s albums, starting with the slide guitar on “Show Biz Kids” from 1973’s Countdown to Ecstasy, the group’s second album. In later years Becker would continue to share the 6-string limelight with Steve Khan, Mark Knopfler, Hugh McCracken, Hiram Bullock, Lee Ritenour, and others.

Becker’s own playing, to say nothing of his gifts as a songwriter and arranger, straddled the worlds of jazz and blues, with an ear for edgy tonalities. His first bellwether 6-string performance was “East St. Louis Toodle-oo” on 1974’s Pretzel Logic, the album that also yielded Steely Dan’s biggest hit: the No. 4-charting single “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number.” In “East St. Louis Toodle-oo,” which had been Duke Ellington’s first hit in 1927, Becker used a talk box to re-create the sound of the original recording’s melody, which was played by Ellington band member Bubber Miley with a muted trumpet. Becker’s take is a brilliant re-imagining, with Baxter mimicking the original’s trombone lines on pedal steel. And on the album’s title track, Becker’s braying tone delivers a series of elegantly soulful fills that culminates in an outro with knotty turns that seem to draw on Charlie Parker as much as Freddie King. Likewise, his soloing in “Black Friday,” from Steely Dan’s next album, and that disc’s “Bad Sneakers” were idiosyncratic in tone and direction. He mixed a big, dirt-dappled sound with lines that are circuitous but logical in their reflection of the song’s fraught emotions.

As the years went by, Becker’s tone got even fatter. Listening to “Lucky Henry,” from his 1994 solo debut 11 Tracks of Whack, which holds 12 songs, the harmonized guitar breaks glide elegantly until a bit after 2 minutes, when he breaks into a series of rising and falling lines that reveal his absorption of the great fusion players with whom he’d shared the studio. And Becker’s fireworks finale is a wholly unpredictable fusillade of whammy bar aerobics and squealing overtones that conjure visions of Ike Turner and Roy Buchanan in a 6-string battle royale.

Becker was a native of Queens, New York, and met Fagen in 1967, when they were both students at Bard College. They started writing songs imbued with the tart cynicism—something they shared, along with a love for early jazz, the Marx Brothers, W.C. Fields, science fiction, and blues and soul music—that would become one of Steely Dan’s signatures. Leather Canary, one of their college bands, included Chevy Chase on drums.

After Fagen graduated, Becker dropped out and they both moved to New York City. Their first successful venture was the soundtrack for 1971’s You’ve Got to Walk It Like You Talk It or You’ll Lose That Beat, a grade-C movie about a hippie’s search for the meaning of life. Emboldened, they moved to California and formed Steely Dan. The first lineup included both Dias and Baxter, so Becker chose to play bass on the songs he wrote for the band with Fagen, who played keyboards and sang. It took three albums for Becker to take a guitar slot in Steely Dan and he distinguished himself immediately.

YouTube It

In this live performance from Late Show with David Letterman, the reunited Walter Becker and Donald Fagen play “Josie,” one of the singles from Steely Dan’s 1977 Aja. Starting at 2:20, Becker faithfully recreates the solo he played on the original studio recording.

By 1975, Becker and Fagen had tired of touring and Steely Dan became exclusively a studio project. Nonetheless, for four more albums, the band was a constant presence on FM radio, where they eventually became a staple of the classic-rock format. In 1981, after the release of Gaucho and a series of personal traumas for Becker that included the death of his girlfriend by overdose, being struck by a cab, and suffering his own deepening drug dependency, Becker and Fagen went on hiatus for a dozen years.

Becker moved to Hawaii and overcame his addiction. He also began producing other artists—most notably Rickie Lee Jones, Michael Franks, and China Crisis. In 1991, he joined Fagen in the New York Rock and Soul Review, which toured widely and reopened the doors for a Steely Dan reunion. Rediscovering their love for making music on the road together, Becker and Fagen kept Steely Dan touring sporadically in the ’90s and released a live album in 1995. They ended the decade by recording their first studio disc in 20 years, 2000’s Two Against Nature, which won four Grammy Awards. The duo followed that with 2003’s Everything Must Go, and Becker put out his second solo album, Circus Money, in 2008. Becker embarked on a handful of other collaborations, and co-wrote songs with Madeleine Peyroux for two of her solo albums. Steely Dan continued to play occasional gigs, too, and Becker’s absence from a pair of classic rock festivals in July prompted an announcement from Fagen that his musical partner was recovering from a medical procedure. The news of his death was revealed at walterbecker.com.

His daughter, Sayan Becker, soon posted a loving tribute on the website, in which she recalls her father’s sense of humor and zest for life, and his abiding love for guitars. “Every road trip, without fail came the Pit Stop at some guitar store,” she wrote. “Heck, dad, I keep telling you why don’t you just own your own store? Five hours go by as I sit watching you fiddle with a guitar here and there … and yet you never end up buying one. I understand though; it was your fun place, like an arcade; playing all you can and as loud as you can. Your candy shop.”

![Fontaines D.C. Rig Rundown [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/image.jpg?id=60290466&width=1245&height=700&quality=85&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Mustang Muscle

Mustang Muscle